Ben Arogundade’s Book

Black Beauty:

A History Of

The Black Aesthetic,

From Antiquity

To The Present

Back in 2000, Ben Arogundade‘s book,

Black Beauty was first released, to

wide acclaim. Now he is back with a

revised eBook edition that contains

new and shocking conclusions.

BLACK BEAUTY THROUGH THE AGES: Above; A selection of black stars and personalities featured in Ben Arogundade’s ebook edition of ‘Black Beauty’. The narrative documents the history of black and African American make-up, hair and beauty, from the first recordings by European writers and travellers right through to todays black celebrities of the stage and screen. Available here in all digital formats.

Available for MAC, Kindle and all digital formats: £6.99/$10.99.

Don’t have an ereader? Download a PDF instead.

HOW DID MARTIN LUTHER KING change the face of fashion? What did Malcolm X think of hair straightening? Why did the Afro go out of fashion? Who spat in the face of a well-known fashion designer because he used black models? What lies behind the blonde ambition of Rihanna, Beyoncé and Nicki Minaj? How did natural hair become nasty?

Find out the answers to these and many other thought-provoking questions in this third edition of Ben Arogundade’s best-selling book, Black Beauty. Originally published as an illustrated hardback in 2000, with a second edition in 2003, this new digital edition has been extensively revised specially for the format.

The history of black and African American hair, make-up and beauty is a complex narrative. The new eBook edition of Black Beauty chronicles the way in which the aesthetics of blacks and African Americans have fared throughout Western history and culture, from antiquity to the present. It analyses styles of make-up, hair, skin-tone and facial features, and the way that they have historically been both accepted and rejected within society. The narrative draws on the galaxy of African American stars of film, fashion, music, television and sports. From Josephine Baker to Beyoncé, from traditional African hairstyles to color contact lenses and blonde weaves, Black Beauty has become the key text for all studies of this branch of beauty history.

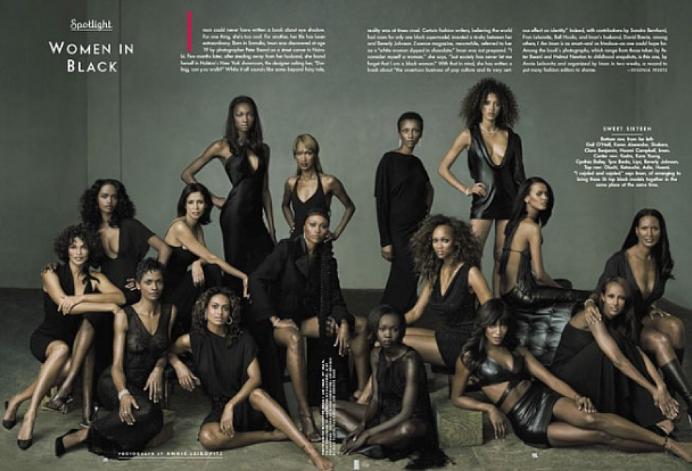

BLACK BEAUTY ROLL CALL: Below; For the November 2007 edition of ‘Vanity Fair’, photographer Annie Leibovitz brought together a collection of black supermodels, past and present, for this special commemorative photograph. Amongst those present are Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks, Iman, Alek Wek and Noemie Lenoir.

The new edition is available online in eBook format for all computers, tablets and smartphones.

READ THE ENTIRE FIRST CHAPTER FREE, BELOW.

(Note: the images shown in the photo carousel above are not included in the ebook edition).

CHAPTER 1 — BLACK IS (NOT) BEAUTIFUL

Early European Perceptions Of Africans

In the beginning, beauty belonged to nature. It was raceless and classless. Beauty only had one rule, and that was that it was not gifted to everybody. Life was for everybody, but not beauty.

The gods of genetics assigned each population their quantity. And even here in its original format beauty was a corrupt commodity. It was nature’s fascism — the gift that gave certain people power over others. Such was nature’s elitism. At the dawn of humankind beauty was said to have evolved as a biological signalling system that people used to identify the fittest candidates for procreation. Beauty was the original ‘money’, the currency of survival, and it was just as corrupting. This was the way of life. The way things were designed to be.

Events turned when powerful patriarchs learned to harness beauty’s power. Suddenly beauty was in the eye of the beholder, and the beholders were white. As colonialists, the definition of beauty became their prerogative, as it would any conqueror. Consequently, a new racially defined theory of beauty began to evolve, with a singular European template.

In ancient Greece the profiles of Apollo and Venus were promoted as examples of the ideal human face. Later, German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer devised a proportional system that positioned Europeans as paradigms of physical perfection, and which was subsequently to govern the aesthetics of Western fine art for centuries. In 1799, in The Regular Gradation of Man, English surgeon Charles White declared the superiority of white beauty when he stated that, ‘Ascending the line of gradation, we come at last to the white European, who being the most removed from the brute creation, may, on that account, be considered as the most beautiful of the human race.’ Simultaneously, whiteness was promoted as the colour of all things virtuous, clean and beautiful. White skin, in combination with red cheeks, was regarded as beauty’s most desirable hue by the Elizabethans. The Queen herself, with the aid of make-up, had cheeks that were likened to ‘roses in a bed of lilies,’ by poet and painter Edmund Spenser.

White beauty ruled. It was written, and it was practised.

WHEN AFRICANS BEGAN arriving as slaves in Europe and the Americas in the mid-fifteenth century, they did not fit the prevailing beauty standard. Indeed, black beauty appeared to be the exact opposite of white. They had broader noses, fuller lips, tightly curled black hair and dark skin. These aesthetic variations became one of the primary catalysts for the theory of racial inferiority put forward by Europeans as a justification for the slave status of Africans. Using a combination of pseudo-science, religious folklore and pure invention, they fashioned the notion that Africans belonged to a separate, sub-human anthropology. This notion of ‘difference’ was not simply a product of their appearance, but was also tied to the fact that when Europeans discovered Africa they found that its inhabitants spoke no English, wore little or no clothing and practised their own religious and sexual customs, all of which seemed alien to the Christian way of life.

The black aesthetic provided a useful counterpoint by which Europeans could further define white beauty values. In 1774, in A History of the Earth, Irish naturalist Oliver Goldsmith set the tone when he stated that, ‘we may consider the European figure and colour as standards to which to refer all other varieties, and with which to compare them.’ This began with the contrast between black skin and white. The Bible’s so-called ‘Curse of Canaan’ (often referred to as the ‘Curse of Ham’) was used as one of the starting points for the theory of racial inferiority, and as an explanation for the skin colour of Africans. Genesis 9:20-27 relates the story of Noah and his family after they exit the ark. According to the scriptures, Noah took to farming, planted a vineyard and one day got drunk from the wine it produced. He then passed out in his tent, where his clothes accidentally fell away from his body, leaving him naked. There, he was discovered by his youngest son, Ham, who saw his father’s nude body but failed to cover him, instead informing his two brothers Shem and Japheth, who were outside. They then averted their eyes, entered the tent and covered their father. But when Noah awoke and learned of what had taken place, he promptly cursed not Ham, but Ham’s son, Canaan for dishonouring him in failing to preserve his dignity:

And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of

Servants shall he be unto his brethren.

Thus, Canaan was to be sentenced to eternal servitude — interpreted to mean slavery. Although it makes no mention of skin colour, Europeans extrapolated the belief that Africans were the direct descendants of Ham’s cursed son, and that the blackness of their skin was an indelible mark of their scriptural misfortune. Historians such as Winthorp D. Jordan have suggested that this interpretation may have resulted from the fact that Africans have been enslaved by Europeans since ancient times.

Christian scripture is founded on metaphors of light and dark. References to ‘God’s light’ counterpoint with the evil, the ungodliness of the dark, or the dark side, as the enemy of spiritual light. Throughout ancient times, this symbolism was misinterpreted by Europeans, and given new meaning, in flesh. Whites positioned themselves as God’s chosen people, and Africans came to represent the dark side, like a nation of Darth Vaders. And so the concept of race, and racism, was born.

This idea found form, not only in Africans, but also in art. In early medieval paintings black devils were depicted as Christ’s tormentors during the Passion. Within popular medieval English drama, the fall of Lucifer, the devil, was often illustrated by his skin changing from light to dark. Shakespeare’s Othello is famous for the poetic racism of its prose in deriding blackness. Iago speaks of how he plots against Desdemona, threatening to ‘turn her virtue into pitch’, while the Moor, as he believes his wife to be guilty of adultery, equates her discredited character with his own complexion:

Her name, that was as fresh,

As Dian’s visage, is now begrim’d and black As mine own face.

Prior to the sixteenth century, The Oxford English Dictionary followed the same line, defining ‘black’ as ‘Deeply stained with dirt; soiled, dirty, foul….Having dark or deadly purposes, malignant; pertaining to or involving death, deadly; baneful, disastrous, sinister…..Foul, iniquitous, atrocious, horrible, wicked….Indicating disgrace, censure, liability to punishment, etc.’ Accompanying this were negative terms such as ‘blackmail’, ‘blacklist’, ‘black death’, ‘black magic’ and ‘black sheep.’

The advent of slavery crystallised these derisory connotations further. In 1897 in Richmond, Virginia, African American Paul Davis was shot dead as he was moved from the jail to the courthouse to stand trial for rape. In the ensuing press reports false pictures of him were published and altered to make him appear darker, to ‘prejudice public sentiment against him,’ according to local African American newspaper editor John Mitchell. A century later Photoshop would be used in a similar fashion to demonize the visage of OJ Simpson during his trial for the alleged murder of his wife, Nicole.

In the French West Indies in the seventeenth century, Catholic missionary Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre expressed his abhorrence for blackness and those who mixed with them. ‘Our French colonists….allow themselves to love their Negro slaves, in spite of their black faces which make them hideous,’ he said. Further, in Notes On Virginia (1784), Thomas Jefferson contrasted the beauty of white skin with the alleged ugliness of blackness when he posed the question, ‘Are not the fine mixtures of red and white….preferable to that eternal monotony….that immovable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race?’

A recurring method of denigrating black skin was to suggest that Africans were actually white underneath and that their blackness was a form of staining. The ancient Greeks were first to suggest this. Ptolemy attributed blackness to the effects of being burnt by the sun, a theme denoted in Phaeton’s fable:

The Ethiopians then were white and fayre,

Though by the worlds combustion since made them black

When wanton Phaeton overthrew the Sun.

European folklore and illustrations soon adopted this theme. In 711 A.D. when the Moors invaded southern Spain from North Africa, a soldier from the Muslim army was taken prisoner by the Visigoths. His captors had never seen a black man before and so they attempted to scrub off his colour. In the late nineteenth century this concept was appropriated in the promotion of goods associated with whiteness, namely soap, washing powder and toothpaste. Drawing on the notion of ‘removable blackness’, the advertising utilized the ideal of purity through acquired whiteness. Typically they depicted blacks in graphic scrubbing or washing scenarios in which the endgame was to eliminate the difference between blacks and whites. At the heart of the metaphor was the idea that whiteness would spiritually cleanse blacks and imbue them with goodness and beauty. It was a subliminal call for them to assimilate European aesthetic values in order to be accepted.

The negativity of blackness evolved a stage further in 1820s America with the advent of minstrel shows. Minstrels were white performers with faces blackened with make up, that caricatured the song-and-dance style of the archetypal plantation slave performer. The minstrel look was the ugly face of nineteenth century Americana, a grotesque logo come to life. The image, designed to deride the aesthetic of black males, relied upon comic ridicule for its power, and this was conveyed through its trademark grimace-and-eyeball facial expressions, together with its clownish make-up, combining a black face with oversized white lips. The colour of the face paint — a wax made from the ashes of burnt cork mixed with animal fat — was very significant. Of all the tones within the spectrum of black beauty, the minstrels chose Africa’s deepest hue — jet-black. This was the colour furthest from white and therefore considered the least attractive. Compositionally it also provided the most extreme contrast for the bulbous white eyeballs and white lips of the minstrel signature, further enhancing its comic impact. More importantly, jet-black was the tone of unmiscegenated blackness, making it abundantly clear that the subjects of ridicule were not to have any resemblance to Europeans.

The success of minstrel shows amongst European audiences was such that in the 1860s African Americans formed their own copycat shows. It was a commercial move that saw performers such as Amos ‘n’ Andy, Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle appropriate the white insult in the same way that hip-hop would later re-cycle the word ‘nigger’ as a term of endearment. Putting political correctness aside, they mimicked the blackface mask in order to secure better paid engagements in white-owned theatres, where minstrels shows were smash hits. Essentially, in adopting the minstrel motif they were not deriding themselves as blacks, but rather, whites comic caricature of themselves. It was a parody of a parody. Minstrelsy belonged to white culture, not black, and as such it was as much a product of white America as Marilyn Monroe.

Simultaneously, black female performers also found themselves having to adopt aesthetic values that appealed to white tastes. The vaudeville entertainers of the late nineteenth century mimicked the look of white artists by wearing straight-haired wigs made of horsehair, establishing a trend that remains unchanged to this day.

In the same way that the minstrel genre was predicated upon the colour of unmiscegenated Africans, black male performers outside of blackface also had to correspond to the same conventions of skin-tone. This was due to white prejudice that focused around African Americans performing on stage with white women. It was easier for whites to police their desire for segregation by removing any ambiguity about the ethnicity of the male entertainers. This formalised the requirement for male performers to be dark-skinned. During the late nineteenth century the ads for African American performing artists carried specifically worded requests for ‘real black men only’.

Meanwhile, in the American South in the 1890s, the minstrel-style monotone contrast of white eyeballs and teeth against a blackface backdrop precipitated the derisory term ‘coon’ — named after the raccoon, with its trademark black-and-white colouring — which took the form of a cartoon-like illustration associated with the promotion of African American music. Whites soon evolved their own copycat equivalents of the minstrel coon, which they quickly took to their hearts like national mascots. Britain for example, created the ‘Gollywog’, while France promoted ‘Banania’, Holland devised ‘Black Peter’, Germany developed the ‘Sarotti-Mohr’.

INTERRACIAL RELATIONS WITHIN slave culture created a new colour caste within black beauty. The offspring of black-white liaisons were called ‘mulattoes’, after the traditional Spanish word for ‘mule’, which was used to describe a person of Afro-Spanish descent. It was appropriated in the mid-1600s by the Americans and the English in the Caribbean. A further range of sub-classifications were also employed to define other degrees of racial mixture. While the ‘mulatto’ was half white, a ‘quadroon’ was three-quarters white, a ‘sambo’ a quarter white, and a ‘mestize’ was seven-eighths white.

Regardless of their degree of European ancestry, all such citizens were legally classified as slaves, and thereby the property of the slave-owner of their descendents. Post-slavery, this hierarchy was maintained by America’s so-called “one-drop rule” — a series of laws first passed in the early 20th century, and which classified as legally “black”, any individual with as little as “one drop” of “black blood” within their family history, regardless of any white ancestry. The legislation was designed as a means of using African genealogy to constrain all children of biracial unions to a lower socio-economic status within post-slavery society. The rule was first passed into law in Tennessee in 1910. By 1931, most states in America had adopted some form of one-drop law. Although the last of these laws are now gone — repealed in the late 1960s — their original classification remain very much in use today.

However, long before the one-drop rule, the presence of mixed-race slaves created a new skin-tone-based class system within black beauty that remains in place today. Light skin acquired a value that relegated unmiscegenated blackness, along with African features, to a lower beauty rating. Mixed-race slaves, by virtue of their more European countenance, were favoured by the ruling class of whites as the closer approximation to their own beauty ideals. The mulatto was rendered version 2.0 of black beauty, a new strain positioned somewhere in the furrow between black and white. Aesthetically, they were seen as ‘African-lite’, easier on the European eye than the aesthetic from which they came. Like the earlier advertising metaphor of washing blacks white, the closer an African became to the dominant beauty ideal, the more they would be accepted.

Across the slave Diaspora mulattoes attained privileges denied to their darker-skinned counterparts. In Spain they were admitted to the priesthood and other posts of the higher classes. In many slave territories dark-skinned Africans routinely toiled in the fields while mulattoes worked in the house as favourites of their white masters. Throughout the colonies the mulatto concubine became the stereotype white slave-owners favourite sex toy, and at slave auctions they often fetched a higher price than their darker-skinned counterparts.

After slavery they were promoted by whites as their favoured style of black female performer. African beauty values were considered ‘too black’ to appeal to the mainstream. Early African American revues of the 1890s such as The Creole Show and The Octoroon — and later the chorus girl revues of New York — set the trend by exclusively casting female performers of mixed-race.

Mulatto privilege established the mixed-race female as the original ‘blonde’. Just as Hollywood promoted the twentieth century blonde to outshine the brunette, who then envied her for the privileges attained by the lightness of her hair, so the mixed-race belle acquired the same status over her darker sisters, in this case channelled through skin-tone. Mulatto ambition signposted the desire of dark-skinned Africans for the social privileges accrued to the lighter class.

Nevertheless, being mulatto had its problems. Its crossover style of beauty was destined to be caught in the acceptance gap between being too light for ‘genuine’ blacks, while being rejected by whites for her African ancestry. This would become a popular theme of the race movies of the 1930s and 1950s.

Simultaneously, the coffee-coloured skin-tone of mixed-race beauties was frowned upon by the upper class of white women. Before sun tanning became chic in Europe in the 1920s — courtesy of fashion designer Coco Chanel — the wives of plantation-owners in America and the West Indies scrupulously shielded their faces from the sun for fear that a tanned skin might imply some trace of African ancestry.

Aside from black skin, every other component of the physical architecture of African beauty was subjected to negative scrutiny. In 1774, in History of Jamaica, an account of slavery in the West Indies, English judge and plantation-owner Edward Long made no effort to conceal his disgust for black beauty when he referred to their hair as ‘a covering of wool, like the bestial fleece.’ Meanwhile Francis Moore, who toured Gambia in the 1730s, expressed disdain at the ‘thick Lips and broad Nostrils’ which Africans ‘reckon;d the Beauties of the Country.’ In the early 1800s Swiss anatomist Georges Cuvier contended that ‘The projection of the lower parts of the [African] face, and the thick lips, evidently approximate it to the monkey tribe.’ Derogatory references to the lips of Africans became a popular motif in everything from Shakespeare’s Othello to minstrel make-up.

European scholars used the pseudo-science of comparative anatomy to prove that Africans were aesthetically inferior. In the 1770s Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper, by measuring the angles of human facial profiles, claimed to have discovered the angle of beauty, which he set at 100 degrees — a figure taken from the ancient Greek statues of Apollo and Venus. He arranged the skulls of different races into a ‘league table’ of beauty that positioned Europeans at the top and Africans at the bottom. Similarly, German physiologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach divided the human race into five racial categories defined in terms of their physical features, declaring Europeans the ‘most handsome and becoming.’ He invented the term ‘Caucasian’, which he derived from the Caucasus region of Eastern Europe, where he believed the most beautiful members of the white population resided.

Further, the theory of ‘race science’ sought to establish links between physical appearance and criminal behaviour, in much the same way that blackness had been equated with evil since ancient times. In 1874 Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso published L’homme criminel, in which he contended that the lips of rapists and murderers were ‘fleshy, swollen and protruding, as in Negroes.’

The notion that blacks were ugly was not simply confined to beauty, but was also extended to their sexuality. The Bible’s Curse of Ham was used to suggest that Africans were grossly libidinous and that they had larger penises than white men. This particular claim was first made by Richard Jobson, an English sea captain and trader who toured the West African coast in 1620. Three years later he published his travel diary, The Golden Trade, in which he stated that the African males he’d observed were ‘furnish’d with such members as are after a short while burthensome unto them.’ He went on to claim that ‘undoubtedly, these people originally sprung from the race of Canaan, the sonne of Ham, who discovered his father Noah’s secrets, for which Noah awakening, cursed Canaan as our holy Scripture testifieth…..extended to his ensuing race, in laying upon the same place where the original cause began, whereof these people are witnesse.’

Here, Jobson implies that African men were blighted in the same part of their anatomy — i.e. the penis — that was involved in the original offence against Noah when his clothes fell away from his body and revealed his genitals. Jobson presumes this to be justification for their allegedly larger penises, although it seems a bizarre concept that God’s curse would be to actually make their penises bigger rather than smaller.

Nevertheless, one of the world’s oldest racial stereotypes was born. Over the next three centuries Jobson’s claims were reiterated by other European writers and travellers. In 1745 Thomas Astley, in A New General Collection Of Voyages, cited Jobson in claiming that ‘The reason of the [African] woman abstaining from coition after pregnancy is the danger of abortion from the enormous size of the virile member among the Negroes.’ In other words, African penises were so large as to rupture a sleeping foetus in the womb.

The sexual organs of black women did not escape scrutiny. In 1774 Edward Long derided the ‘general large size of the female nipples [of Africans], as if adapted by nature to the peculiar confirmation of their children’s mouths.’ Less than a century later, French anthropologist J.J. Virey stated that ‘All negro women have large, flaccid and pendulous breasts.’ The vagina of the African female was also said to have different dimensions to white women. As recently as the 1940s, this was still a popular myth. ‘The vagina in the black races is said to be longer than in women of white races,’ said Dr. Julian Herman Lewis in Biology of the Negro.

The myth of a separate African biology — deformed, oversized, and closer in design to animals than humans — was a powerful catalyst in the advent of human zoos that spread through Europe’s colonial nations in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, the culture of putting humans on display dates back to the empires of ancient Egypt and Rome, where triumphal processions paraded prisoners of war along with captured war treasures. In 1845 an African slave boy named Jozef Moller was given away to Holland’s Antwerp Zoo. He lived there in a dual role, both as an exhibit and caretaker. He later married a white Dutch servant girl in the zoo’s Ape House — home to almost 80 primates.

Things were no better in Germany. In 1874 animal trader Carl Hagenbeck, who had hunted and captured all manner of wild animals from the jungles and mountains of the world, exhibited Samoan and Sami peoples in his Hamburg zoo alongside his menagerie of animals. Two years later he toured Paris, London and Berlin, displaying Sudanese and Inuit captives to enthusiastic white crowds. Another tour took place in 1810, this time with Saartjie Baartman, better known as the Hottentot Venus. This South African slave from the Khoi-Khoi tribe of hunter-gatherers was put on display in London, Paris and Ireland — naked and caged. The star of her own freak show, she was presented to audiences as a kind of African version of the Elephant Man. Her pronounced derriere and genitalia were paraded as an example of the sexual extremities of African womanhood. After she died at the age of 25 her genitals were dissected and displayed in floating chunks inside glass jars of formaldehyde at the Musée de l’homme in Paris until the mid-1970s. Her remains were finally returned to South Africa in 2002.

Simultaneously, the African libido was claimed to be closer in design to animals, particularly primates. Edward Long described black men as ‘libidinous and shameless as monkeys, or baboons.’ As regards black women he even suggested that they actually had intercourse with primates. ‘They [orangutans] sometimes endeavour to surprise and carry off Negro women into their woody retreats in order to enjoy them.’

However, while some Europeans denigrated blackness, there were others who eulogized its specialness within Western culture. Unlike the Europeans of the slave era, in ancient Greece and Rome there was little stigma attached to black beauty, and they devised no racially based theories of inferiority. African goddess figures such as Minerva, Artemis, Diana of Attica and Isis were worshipped within ancient Greek mythology. Artists favoured Africans as models, and representations of black beauty feature extensively in all forms of artwork, from coins to statues. In 270 BC the poet Asclepiades scribed a verse in praise of black women. ‘With her charms, Didymee has ravished my heart. Alas, I melt as wax at the sight of her beauty. She is black, it is true, but what matters? Coals are also black; but when they are alight they glow like rose cups.’

African queens of antiquity such as Andromeda, Hatshepsut, Nefertiti and the Queen of Sheba have carried the iconography of black beauty through the ages, while historical representations of the black Madonna and child feature extensively in the religious art of Spain, France, Poland and Russia, covering a range of shades from light brown to deep black, mirroring the actual skin-tone spectrum present within black beauty.

References to black male beauty have focused on warriors and folk heroes such as Saint Maurice, the black knight of the Roman army and patron saint of the Crusade against the Slavs, who was immortalised in a statue in Magdeburg in 1245, or African ruler Caspar, King of the Moors who was depicted as a handsome nobleman in paintings and plays.

From the sixteenth century onwards, images of people of colour featured regularly within the European fine art tradition, from Rubens to Rembrandt, albeit mainly within slave-related roles as servants or courtesans. In the late 1890s Paul Gauguin captured the dignified beauty of Tahitian women, while German artist Frank Buchser painted African female nudes, and sculptors Alessandro Vittoria and Charles Cordier produced black Venuses. In the late nineteenth century black beauty became part of Europe’s avant-garde, and African masks and sculpture had a profound influence on the work of Picasso and Matisse, who both became avid collectors.

European literature also eulogized blackness. In The Two Gentlemen Of Verona, Shakespeare’s character, Proteus acknowledges the aesthetic appeal of African males. ‘Black men are pearls in beauteous ladies’ eyes,’ he says. French poet Baudelaire scribed exotic fantasies to La Venus Noire, whom he described as a ‘strange goddess, dark as the nights’.

A clear sign that black beauty was becoming an accepted part of pop culture was in their use as models in advertising. The earliest examples began appearing in the 1850s, and reflected slavery’s established stereotypes. Blacks were used to promote household food items and products associated with servitude such as cocoa, chocolate, rum and coffee. They were depicted, not as consumers but as servants and entertainers. Their facial expressions were caricatured, with the exception of the fantasy Creole belles that adorned the labels of rum bottles from the West Indies. In America, illustrations of black faces began appearing on food packaging in the late 1890s. They drew on slavery’s nostalgic stereotype of the smiling, happy-go-lucky domestic servant. The first black ‘model’, Nancy Green, an ex-slave from Kentucky, became one of the earliest iconic logos in 1889 when she was rendered as Aunt Jemima on packets of Quaker Oats and The Original Pancake & Waffle Mix.

Perhaps the most obvious evidence of the allure of black beauty was to be found in the interracial relations that took place within slavery. Despite public pronouncements of their perceived ugliness and inferiority, both forced and consenting sex with African females was a routine part of the culture, particularly for white slave-masters, who were mired a complex swirl of power, control, desire and shame. Pretty African slaves were sold as high-price sex objects, providing brutal testimony of their potent sex appeal. On June 26, 1857 The Memphis Eagle & Inquirer reported one such example of a slave woman ‘advertised to be sold in St. Louis, who is so surpassingly beautiful that $5,000 has already been offered for her at private sale and refused.’

Interracial sex permeated every level of society, from peasants to presidents. In the late 1700s Thomas Jefferson, despite his public disapproval of interracial couplings and pronouncement that blacks were ugly, sustained a long-standing affair with his then teenaged light-skinned slave Sally Hemmings — a fact that was finally proved via DNA testing after over a century of speculation and denial. The fact that one of America’s most revered statesmen concealed his illicit liaison was typical of the times, as the embarrassment and shame of desire for those branded as inferior revealed their hypocrisy, while acting as a snub to the paradigm of white womanhood.

The history of the clergy and the royal families of Europe are filled with examples of high-profile whites adopting black lovers. In fifteenth century Italy, Pope Clement VII, formerly Cardinal de Medici, had an affair with Anna, a beautiful black servant dubbed ‘the Italian Cleopatra’. Elsewhere, Afonso III of Portugal and Francis I, Louis XIV and XV of France all had African lovers, as did Robert d’Eppes, son of William II of France. It was rumoured that Count d’Artois, the future king Louis XVI, had an affair with famed African courtesan Isabeau, who wowed eighteenth century Paris like a prequel to Josephine Baker. According to fellow concubine Madame du Barry, she was ‘a black Venus that all Paris ended by admiring.’ The sexual favours of African men were also sought within select royal bedchambers. Queen Maria Theresa of Spain, wife of King Louis XIV, caused a royal scandal when she had an affair with her teenage African servant Osmin, which yielded an illegitimate child, Opportune, otherwise known as the Black Nun of Moret.

Despite history’s patchwork endorsements of black beauty, the overriding effects of four hundred years of European culture would weigh heavily on the consciousness of blacks in the West. As they entered the twentieth century they found themselves immersed in a culture which said that light skin was better than dark, straight hair was better than curly hair, African lips and noses were unattractive and that blacks were genitally malformed, bestial and excessively sexual. Who would dare be black at times like these?

Download the full text of Ben Arogundade’s Black Beauty

++++++++++++

ABOUT BEN AROGUNDADE