/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

May 8, 2014

In Push to Free Nigerian Girls,

a Tangled Web

When Twitter Hashtag Went Viral, American Woman Took Credit, Then Admitted She Didn’t Create It

By ELIZABETH WILLIAMSON, NATALIE ANDREWS and MICHAEL M. PHILLIPS

Despite growing national and international anger, the president of Nigeria spoke Thursday and gave no specifics as to what the government was doing to rescue the more than 200 abducted school girls and end the continuing attacks from Boko Haram. Jerry Seib reports. Photo: AP.

It is an irresistible story line: An American mom hears of terrible wrongs done to poor girls the age of her own daughter in a faraway land, then galvanizes social media, prompting the U.S. to act.

Soon, first lady Michelle Obama is holding up a placard with the maternal cry for help: #BringBackOurGirls.

But the real tale of how a Twitter TWTR +0.28% hashtag grew into a rallying call for more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the Boko Haram terrorist group is a more complex web.

In her online biography and in interviews on CNN and ABC, Ramaa Mosley has portrayed herself as a mother who until recently “didn’t even know what a hashtag was.” She said that two weeks ago, she was moved to tears by a brief radio broadcast about the mid-April abductions in Nigeria, and adapted the cries of the girls’ mothers into the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls.

Elizabeth Smart, a former child abductee turned activist, talks to the Wall Street Journal’s Lee Hawkins about the more than nearly 300 girls who are missing in Nigeria and reveals what she would tell them if she could speak with them now. Lee Hawkins reports.

“I quickly noticed that there was no social media presence, no petitions, no action cry. So pathetically I set out to create a Facebook page and Twitter account for the cause…then I began tweeting and hashtagging one particular phrase #bringbackourgirls,” she said in an April 30 message about herself on her Facebook page.

In fact, Ms. Mosley also helped direct the film “Girl Rising,” a well-received documentary about the global struggle to educate girls, and her effort to draw attention to the kidnappings is part of a push by The Documentary Group, a for-profit company, to promote the project world-wide.

CNN Films paid $500,000 last year for three years’ rights to the film, and will air it again on CNN International this weekend.

CNN had no comment.

The “Bring Back Our Girls” hashtag—retweeted nearly two million times so far by Twitter users including the Vatican, the first lady and celebrities including singers Mary J. Blige and Chris Brown—wasn’t created by Ms. Mosley but by Nigerian Ibrahim Musa Abdullahi, a 35-year-old attorney in the capital Abuja who adapted a chant he heard on television there. This week, Twitter users began calling attention to that fact in a storm of angry tweets to Ms. Mosley.

Ms. Mosley said in an interview on Thursday that she didn’t take credit for the hashtag: “The idea that people are so upset has been a complete shock.…I felt compelled to help spread the word.”

She said she thinks she became the face of the cause in the media because “we don’t have photos of the [Nigerian] girls so the media in the United States has picked up on this as a human-interest story and attached me to it.”

On Thursday, after receiving a call from The Wall Street Journal and noting the adverse Twitter reaction to its story, ABC deleted the headline “Los Angeles Mother of Two Creates Viral Hashtag” and posted an editor’s note that read: “This story has been updated to reflect that #BringBackOurGirls appeared on Twitter prior to Ramaa Mosley’s first tweet.”

An ABC spokeswoman had no further comment.

Holly Gordon, founder of the Girl Rising project, said in an interview on Thursday that the Nigeria kidnappings provide “an important moment for us to promote our film.”

Ms. Gordon said Ms. Mosley’s idea for her social-media campaign was solely her own, and Girl Rising helped her to expand her social-media network by linking to its own.

The company said it designed the distinctive red avatar Ms. Mosley used on her social-media pages, and supplied her with “talking points” on girls’ education.

Ms. Mosley on Thursday said she updated her Twitter account biography to reflect her involvement with Girl Rising, and sent a series of tweets giving credit for the hashtag to its Nigerian creators.

The viral campaign has succeeded in drawing global attention to the Nigerian girls’ plight.

On Wednesday, Mrs. Obama tweeted “Our prayers are with the missing Nigerian girls and their families. It is time to #BringBackOurGirls,” with a photograph of the first lady holding up a handmade sign with the hashtag. It was retweeted more than 47,000 times.

The signature hashtag, which allows Twitter users world-wide to find like-minded people, had its origins in Abuja. On April 23, Mr. Abdullahi was at home watching a televised broadcast of the opening celebration of Port Harcourt’s year as the United Nations’ world book capital.

One speaker, former World Bank Vice President Obiageli Ezekwesili, took to the stage and helped lead the crowd in a chant of “Bring back our daughters.”

Mr. Abdullahi had just a few hundred Twitter followers, but he is an enthusiastic tweeter. So, on April 23, he modified the slogan to “bring back our girls” and tweeted:“Yes #BringBackOurDaughters #BringBackOurGirls declared by @obyezeks and all people at Port Harcourt World Book Capital 2014.”

“I don’t have a daughter so I thought it would be better to make it girls,” Mr. Adbullahi said in an interview from Abuja on Thursday.

It was retweeted just 95 times. But one of those came from Ms. Ezekwesili, who has more than 125,000 followers.

She quickly adopted the hashtag and urged people to use it. She tweeted: “Lend your Voice to the Cause of our Girls. Please All, use the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls to keep the momentum UNTIL they are RESCUED.”

The message soon took on a life of its own.

On April 23, the British Guardian newspaper published an article that was shared more than 35,000 times on Facebook and tweeted more than 3,500 times.

The biggest boost, according to Topsy social-media analytics, came on April 30, when Mr. Brown—the performer who pleaded guilty in 2009 to assaulting his girlfriend, Rihanna, the singer—tweeted the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag.

But soon it was CNN leading the charge. The top #BringBackOurGirls tweets for four of the first five days of May were all from CNN-related accounts.

The Girl Rising film and awareness effort are widely hailed. The project was financed by contributions from corporations led by Intel Corp. INTC -0.15% , private philanthropists, foundations and ticket sales.

Ms. Mosley, 38 years old, has been with The Documentary Group’s Girl Rising project “from the very beginning,” in 2007, said Ms. Gordon, and directed the Afghanistan chapter of the film, which covers girls’ education issues in nine countries.

Ms. Gordon said the budget for the film was $10 million: $3.7 million for production costs, and the remainder for the “campaign,” a global effort to highlight the challenges facing young women in developing nations by screening the film in venues including theaters and nonprofit meetings, along with creating short-subject films for nongovernmental organizations working on such issues as childhood marriage in Ethiopia.

The project’s first and one of its biggest funders is Microsoft Corp. co-founder Paul Allen, through his Vulcan Productions. Mr. Allen and his sister Jody Allen are the film’s executive producers.

Vulcan funded the film because of Mr. Allen’s interest in alleviating global poverty, and has also provided media and promotional expertise.

“We know that if you educate one girl you can break the cycle of global poverty in one generation,” said Carole Tomko, Vulcan’s creative director and general manager. “That community we created and united for change are coming together and doing everything they can do to get these girls released.”

To the degree that Ms. Mosley initially didn’t disclose her involvement in Girl Rising, “That would be unfortunate, because she’s a fantastic storyteller and she just wants to bring those girls home, too,” Ms. Tomko said.

—Peter Nicholas and Drew Hinshaw contributed to this article.

Write to Elizabeth Williamson at elizabeth.williamson@wsj.com and Michael M. Phillips at michael.phillips@wsj.com

__________________________

May 7, 2014

Dear Americans, Your Hashtags

Won’t #BringBackOurGirls.

You Might Actually Be

Making Things Worse.

Simple question. Are you Nigerian? Do you have constitutional rights accorded to Nigerians to participate in their democratic process? If not, I have news you. You can’t do anything about the girls missing in Nigeria. You can’t. Your insistence on urging American power, specifically American military power, to address this issue will ultimately hurt the people of Nigeria.

It heartens me that you’ve taken up the mantle of spreading “awareness” about the 200+ girls who were abducted from their school in Chibok; it heartens me that you’ve heard the cries of mothers and fathers who go yet another day without their child. It’s nice that you care.

Here’s the thing though, when you pressure Western powers, particularly the American government to get involved in African affairs and when you champion military intervention, you become part of a much larger problem. You become a complicit participant in a military expansionist agenda on the continent of Africa. This is not good.

You might not know this, but the United States military loves your hashtags because it gives them legitimacy to encroach and grow their military presence in Africa. AFRICOM (United States Africa Command), the military body that is responsible for overseeing US military operations across Africa, gained much from #KONY2012 and will now gain even more from #BringBackOurGirls.

Last year, before President Obama visited several countries in Africa, I wrote about how the U.S. military is expanding its role in Africa. In 2013 alone, AFRICOM carried out a total of 546 “military activities,” which is an average of one and half military missions a day. While we don’t know much about the purpose of these activities, keep in mind that AFRICOM’s mission is to “advance U.S. national security interests.”

And advancing they are. According to one report, in 2013, American troops entered and advanced American interests in Niger, Uganda, Ghana, Malawi, Burundi, Mauritania, South Africa, Chad, Togo, Cameroon, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Lesotho, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and South Sudan.

The U.S. military conducted 128 separate “military activities” in 28 African countries between June and December of 2013. These are in conjunction to U.S. led drone operations which are occurring in Northern Nigeria and Somalia. There are also counter-terrorism outposts in Djibouti and Niger and covert bases in Ethiopia and the Seychelles which are serving as launching pads for the U.S. military to carry out surveillance and armed drone strikes.

Although most of these activities are covert, we do know that the U.S. military has had a destabilizing effect in a few countries. For example, a New York Times article confirmed that the man who overthrew the elected Malian government in 2012 was trained and mentored by the United States between 2004 and 2010. Further, a U.S. trained battalion in the Democratic Republic of Congo was denounced by the United Nations for committing mass rapes.

Now the United States is gaining more ground in Africa by sending military advisors and more drones, sorry, I mean security personnel and assets to Nigeria to assist the Nigerian military, who by the way, have a history of committing mass atrocities against the Nigerian people.

Knowing this, you can understand my apprehension for President Obama’s decision. As the Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole said yesterday, the involvement of the U.S. government and military will only lead to more militarism, less oversight, and less democracy.

Also, the last time military advisors were sent to Africa, they didn’t do much good. Remember #KONY2012? When President Obama sent 100 combat-equipped troops to capture or kill Lord’s Resistance Army leader Joseph Kony in Central Africa? Well, they haven’t found him and although they momentarily stopped looking, President Obama sent more troops in March 2014 who now roam Uganda, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Consequently, your calls for the United States to get involved in this crisis undermines the democratic process in Nigeria and co-opts the growing movement against the inept and kleptocratic Jonathan administration. It was Nigerians who took their good for nothing President to task and challenged him to address the plight of the missing girls. It is in their hands to seek justice for these girls and to ensure that the Nigerian government is held accountable. Your emphasis on U.S. action does more harm to the people you are supposedly trying to help and it only expands and sustain U.S. military might.

If you must do something, learn more about the amazing activists and journalists like this one, this one, andthis one just to name a few, who have risked arrests and their lives as they challenge the Nigerian government to do better for its people within the democratic process. If you must tweet, tweet to support and embolden them, don’t direct your calls to action to the United States government who seeks to only embolden American militarism. Don’t join the American government and military in co-opting this movement started and sustained by Nigerians.

+++++++++++++++++

Jumoke Balogun is a Nigerian-American. She is the co-founder and co-editor of compareafrique.com. Seeing Nigerians of all tribes and religious affiliation together in her hometown of Oshogbo, in Lagos, Abuja, Kano and elsewhere protesting and controlling the destiny of their nation fuels her to do more and be better. She dreams about handing down a festival of slaps to President Goodluck Jonathan and Patience Jonathan.

__________________________

May 8, 2014

The Real Story

About the Wrong Photos

in #BringBackOurGirls

By JAMES ESTRIN

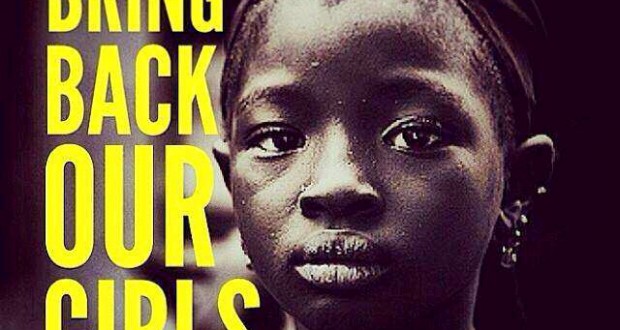

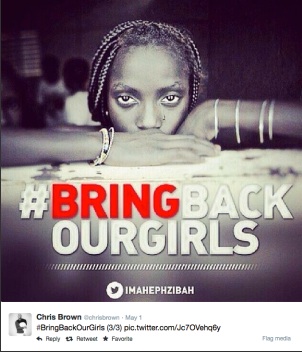

A screen shot taken from Chris Brown’s Twitter account from May 1, 2014, showing the Twitter campaign for #BringBackOurGirls that went viral in support of the Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the Islamic militant group Boko Haram. The girl in the image, taken by Ami VitalGuinea-Biessau in 2000, has no relation to the kidnappings.

A Twitter campaign using the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls has focused global attention on the plight of some 276 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the Islamic militant group Boko Haram. Three photos of girls have been posted and reposted thousands of times, including by the BBC and by the singer Chris Brown (who himself has had issues with anger management and violence against women).

One problem: The photos are of girls from Guinea-Bissau, more than 1,000 miles from Nigeria, who have no relationship to the kidnappings.

The use of these pictures raises troubling questions of representation, and misrepresentation. Ami Vitale, the photographer who made the original images as part of a long-term project, spoke with James Estrin on Thursday. Their conversation has been edited.

Tell me about the photos.

There were three photos that were taken from either my website or the Alexia Foundation website, and someone made these images the face of the campaign. But these photos had nothing to do with the girls who were kidnapped and sexually trafficked.

There are many times when I get upset when people take my photos without permission, but this isn’t about that. I support the campaign completely and I would do anything to bring attention to the situation. It’s a beautiful campaign that shows the power of social media. This is a separate issue.

This is about misrepresentation.

These photos have nothing to do with those girls who were kidnapped. These girls are from Guinea-Bissau, and the story I did was about something completely different. They have nothing to do with the terrible kidnappings. Can you imagine having your daughter’s image spread throughout the world as the face of sexual trafficking? These girls have never been abducted, never been sexually trafficked.

This is misrepresentation.

I know these girls. I know these families, and they would be really upset to see their daughters’ faces spread across the world and made the face of a terrible situation.

The photos were taken from two separate stories. I was there in 1993, in 2000 and then in 2011 for the Alexia Foundation. I lived there for six months, learned the language, learned about their lives and became very close to all the people in these pictures.

What was the story?

I wanted to put a human face on conflict. But when I got there my story changed. Because I realized the way Africa is generally portrayed in mainstream media is either wars, famine or stories like this terrible abduction. You see the horrors or the other extreme, beautiful safaris and exotic animals. There’s nothing in between.

So it’s ironic the story I was telling was that there is a beautiful world that lies between these two truths. Why don’t we ever tell these stories that show the dignity and resilience of these people?

And this is why I feel so enraged, because I was trying to not show them as victims. They are not victims. Using these images and portraying them as victims is not truthful. The story I did was a hopeful story.

Tell me about the girls.

The picture of the girl outside the school was the image used most frequently. The girl’s name is Jenabu Balde, and she is a cousin of thefamily I lived with. Umou Balde is a relative and she is a dear friend. I lived with them and went back in 2011 to visit them. The point of the story was to show that the girls were going to school and life was getting better in many ways.

How did you learn the pictures had been misappropriated?

Eileen Mignoni from the Alexia Foundation spotted this first, and the whole board of the foundation was very quick to respond. Mickey H. Osterreicher [a lawyer with the National Press Photographers Association] has been incredibly helpful as well, citing the legal issues and ramifications.

How do you feel that someone found it acceptable to substitute these girls for the Nigerian girls who were abducted?

This is personal. Even if they weren’t dear friends, it’s the principle. We can’t pick up any photo and use it out of context.

I can’t help but wonder that they thought this was O.K. just because my friends are from Africa. If it were white people from another country in the photos, this wouldn’t be considered acceptable.

What was your arrangement with the subjects of your story?

I feel a sense of responsibility to the people I photograph.

I go into communities and I make a promise that I will be responsible with their images and that I will deliver the message that they articulate to me.

We are responsible as photographers and journalists when we make promises to do justice to their stories and honor them in the way that they have honored us by sharing their stories.

I need to follow through with this one.

How are you following through?

I spent my whole day Wednesday trying to track down the people who are spreading these images.

I tweeted back to scores of people asking them to remove the photos. The BBC and Chris Brown retweeted it and it was everywhere. At first the woman from the BBC refused to take it down because it was already out there in the Twittersphere, But after a long exchange they removed it.

Chris Brown did not respond.

Ami Vitale is a photographer and filmmaker who has worked in more than 85 countries. She is a contract photographer for National Geographic and works with the Photo Society and Ripple Effect Images, and is represented by Panos Pictures. Her photos of Kenyan communities protecting their wildlife from poaching were featured on Lens earlier this year.

Follow @JamesEstrin, @Amivee and @nytimesphoto on Twitter. Lens is also on Facebook.