Tue May 6 2014

Kara Walker interview:

“The whole reason for refining sugar

is to make it white”

The artist’s first public work evokes the not-so-sweet history of sugar and slavery

By Paul Laster

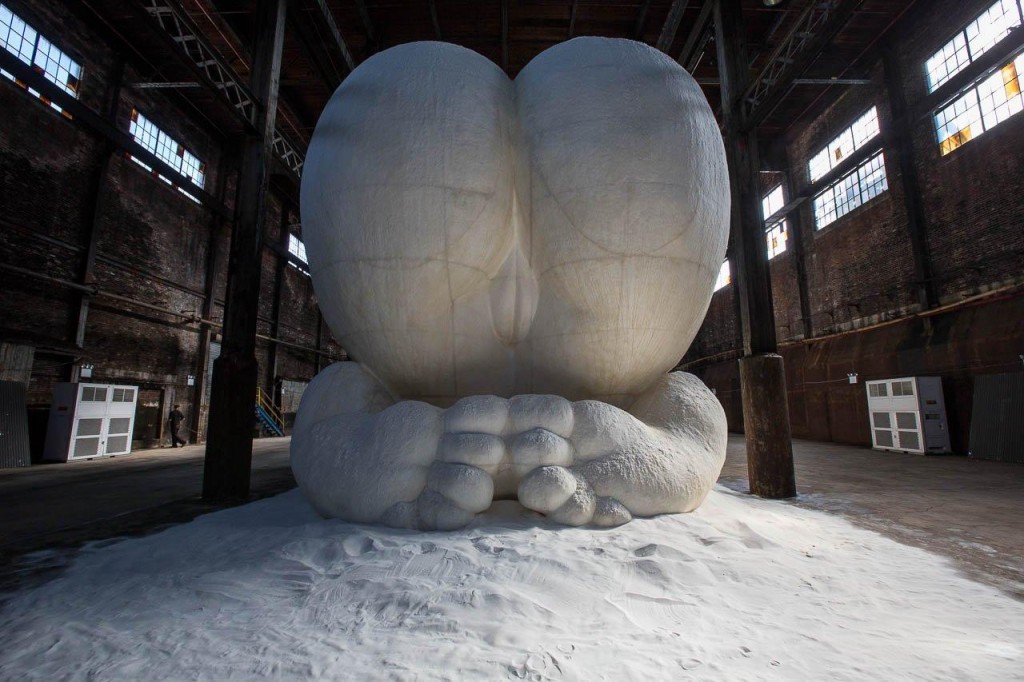

Since her graduate-school days at the Rhode Island School of Design, Kara Walker has courted controversy with her provocative exploration of slavery in America and its connection to present-day issues involving race and gender. Her most notable efforts have been cut-paper murals, done in the style of old portrait silhouettes, depicting antebellum plantation life as a hellscape of violence and sexual abjection. Now Walker is about to unveil her first public artwork, commissioned for the former Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The centerpiece of the project, which references the history of slavery in the 19th-century sugar trade, is a mammoth female sphinx created out of sugar. Time Out New York visited the artist on-site to get her take on the very bitter story behind the sweet stuff.

How did the antebellum South become such a major theme in your work?

I grew up partially around Stone Mountain, Georgia, and in that part of the country, there was always this aura of mythology and palpable sense of otherness about being a Southerner. I mean, Gone with the Wind was playing 24/7 at Ted Turner’s Omni Center in Atlanta. So it’s only natural that I found myself wanting to address the subject once I moved north for school.

How did the Domino Sugar Factory project happen?

[Presenting organization] Creative Time called to say that they had this great site for me, and Nato Thompson, the curator, mentioned in particular the molasses-covered surfaces left in the factory. The image of the tar baby popped into my head, and also this idea of a stickiness or residue that doesn’t go away. I wanted to draw a bridge between themes—not just between slavery and the sugar trade, but between industry and waste—spawned by the fact that molasses is a by-product of processing sugar. And for me, that represents a metaphor for identity formation.

You mean because the factory was originally built to refine brown sugar into white?

Absolutely. The whole reason for refining sugar is to make it white. Even the idea of becoming “refined” seems to dovetail with the Western way of dealing with the world.

How did you settle on using the symbol of a sphinx?

In Greek mythology the sphinx is a guardian of the city, a devourer of heroes and the possessor of a riddle that maybe can’t be answered. The factory is a modern-day ruin, and I think the sphinx contains the various readings of history that the place represents. But she also creates this aesthetic contrast of a white sugar object inside a dark, molasses-encrusted space.

You’ve depicted her in a highly eroticized manner, with huge breasts and an exposed vagina.

Well, yes, she’s a woman, a bootylicious figure with something paradoxical about her pose. She’s both a supplicant and an emblem of power. From the front, she seems to hold her ground. But what you see from behind is what happens when a nude woman bends over, raising a question of whether it’s a gesture of sexual passivity or not.

You’ve also given her a very stern expression.

One of the things I discovered while researching the history of sugar is that the packaging for molasses tended to relate back to slave lore. There was Brer Rabbit Molasses, for instance, and also an Aunt Dinah Molasses picturing a woman in a kerchief. But she wasn’t a smiling, cookie-jar mammy. She had a severe look with a furrowed brow and smirk on her face, so I guess I was thinking of that.

The title for the piece includes the phrase A Subtlety. What does that refer to?

It’s the name for sugar sculptures that were originally made for the tables of Middle Eastern sultans before being adopted by European nobility. A subtlety was a display of power and wealth to impress dinner guests.

So your sphinx is a giant subtlety.

Yes, but by being sexually overt, she’s not very subtle at all. She’s discomfiting. And as far as the riddle she poses, it’s maybe answered in her figure, though as I mentioned before, that only begets other questions.

The sphinx is actually part of an ensemble that includes a group of boys cast in molasses. What do they represent, and what’s their overall function within the installation as a whole?

They’re her attendants, her children. They’re laborers and supplicants, and yet also endearing portraits. They were based on contemporary gift items made in China.

How does this project relate to the rest of your work?

It’s a departure for sure. Not the end of the other work, just an expansion of my horizons. It still deals with the themes that interest me: race, gender, sex and slavery.

The same real-estate developer who will transform the site into condos is also a sponsor of your project. Do you worry that your work is being used as part of the gentrification process?

I don’t see how that could succeed. I have this fantasy that once the installation comes down, the sphinx’s presence will somehow remain. That people will remember something legendary happened here, and that the legend contained histories of sugar and of slavery, and representations of femaleness and sweetness. Sugar is so much a part of our world. It’s this kind of goddess who we give ourselves over to.

See the exhibition

Kara Walker, “A Subtlety or The Marvelous Sugar Baby”

The very long subtitle of Walker’s first ever public-art project reads an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. While the word artisan is a bit vague, the subject of sugar is certainly in keeping with the artist’s career-long investigation of the historical wages of slavery and racism. Sugar was a key leg of the so-called triangle trade that traversed the Atlantic between the 16th and 19th centuries, as European slavers brought their human cargo to the Caribbean in exchange for molasses, which was then transported back to the Continent to be made into rum. Meanwhile, the subtlety of the title refers to sugar sculptures that once adorned the tables of the rich and powerful in Medieval Europe—which, given the rarity and expense of the substance at the time, were meant as displays of wealth. Accordingly, Walker’s project for the old Domino Sugar factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn centers on a giant female sphinx made of the sweet stuff. Although the installation relates to the site’s past, it retains a sphinxlike silence about the location’s future as a complex of office and residential towers along the Williamsburg waterfront.

- Domino Sugar Factory 316 Kent Ave, at South 2nd St

- Sat May 10 – Sun Jul 6

__________________________

MAY 8, 2014

THE SUGAR SPHINX

Over the past twenty-five years or so, ever since her spectacular New York début at the Drawing Center, in 1994, the now forty-four-year-old artist Kara Walker’s visual production—sculptures, cutouts, drawings, films—has been diaristic in tone. But the diary Walker keeps is not explicitly personal; it’s a historical ledger filled with one-line descriptions about all those bodies and psyches that were bought and sold from the seventeenth century on, when slavery became the American way of life and its maiming shadows pressed down on black and white souls alike.

Walker knows that ghosts can hurt you because history does not go away. Americans live, still, in an atmosphere of phantasmagorical genocide—we kill each other with looks, judgments, the fantasies that white is better than black and that blackness is bestial while being somehow more “humane”—read mentally inferior—than whiteness. But what do those colors even mean? In Walker’s view, they are signifiers about power—the power separating those who have the language to make the world and map it, and those who work that claimed land for them with no remuneration, no hope, and then degradation and death.

In her silhouettes, Walker’s black characters are often fashioned out of black paper—the color of grief—while her white characters live in the white space of reflection. But, in recent years, this scheme has begun to change—radically, upping the ante on what Walker might “mean” in her gorgeously divisive work. Take, for instance, the success of Walker’s latest piece:

At the behest of Creative Time Kara E. Walker has confected:

A Subtlety

or the Marvelous Sugar Baby

an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined

our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World

on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant

The title says it all, and then not.

Located in Williamsburg, the Domino Sugar Factory was built in 1882; by the eighteen-nineties, it was producing half the sugar being consumed in the United States. As recently as 2000, it was the site of a long labor strike, in which two hundred and fifty workers protested wages and labor conditions for twenty months. (I saw the piece before the installation was complete and look forward to going back.) Now the factory is about to be torn down and its site developed, and its history will be eradicated by apartments and bodies that do not know the labor and history and death that came before its moneyed hope. The site is worth mentioning at length because Walker’s creation is not only redolent of its history, it’s of a piece with the sugar factory—and its imminent destruction.

Measuring approximately seventy-five and a half feet long and thirty-five and a half feet high, the sculpture is white—a mammy-as-sphinx made out of bleached sugar, which is a metaphor and reality. Remember, sugar is brown in its “raw” state. Walker, in a very informative interview with Kara Rooney, says that she read a book called “Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History.” There, she learned that sugar was such a commodity that, in the eleventh century, marzipan sculptures were created by the sultans in the East to give to the poor on feast days. This tradition made its way to Northern Europe, eventually, where royal chefs made sugar sculptures called subtleties. Walker was taken not only with those stories but with the history of the slave trade in America: Who cut the sugar cane? Who ground it down to syrup? Who bleached it? Who sacked it?

Operating from the assumption, always, that history can be found out and outed, Walker’s sphinx shows up our assumptions: She has “black” features but is white? Has she been bleached—and thus made more “beautiful”—or is she a spectre of history, the female embodiment of all the human labor that went into making her?

Walker’s radicalism has other routes, too: in European art history, which made Picasso and helped make Kara Walker. But instead of refashioning the European idea of coloredness—think about Brancusi and Giacometti’s love of the primitive and what they did with African and Oceanic art—Walker has snatched colored femaleness from the margins. She’s taken the black servant in Manet’s “Olympia”—exhibited the same year black American slaves were “emancipated”—and plunked her down from the art-historical skies into Brooklyn, where she finally gets to show her regal head and body as an alternative to Manet’s invention, which was based on a working girl living in the demimonde.

Walker’s sphinx is triumphant, rising from another kind of half world—the shadowy half world of slavery and degradation as she gives us a version of “the finger.” (The sphinx’s left hand is configured in such a way that it connotes good luck, or “fuck you,” or fertility. Take it any way you like.) Now she’s bigger than the rest of us. Still, she wears a kerchief to remind us where she comes from. She is Cleopatra as worker: unknown to you because you have rarely seen her as she raised your children, cleaned up your messes—emotional and otherwise. Walker has made this servant monumental not only because she wants us to see her but so the sphinx can show us—so she can get in our face with her brown sugar underneath all that whiteness. And, if that weren’t interesting enough, Walker has given her sphinx a rear—and a vulva. Standing by the sphinx, you may recall the playwright Suzan-Lori Parks’s 1995 essay “The Rear End Exists”:

Legend has it that when Josephine Baker hit Paris in the ’20s, she “just wiggled her fanny and all the French fell in love with her.” … [But] there was a hell of a lot behind that wiggling bottom. Check it: Baker was from America and left it; African-Americans are on the bottom of the heap in America; we are at the bottom on the bottom, practically the bottom itself, and Baker rose to the top by shaking her bottom.

The sphinx crouches in a position that’s regal and yet totemic of subjugation—she is “beat down” but standing. That’s part of her history, too.

And then, again, there’s art history. Over the years, we’ve seen the sphinx at the Pyramids, but have we ever wondered what was beyond that mystery? Walker shows us the mystery and reality of female genitalia while calling our attention, perhaps, to all those African women whose genitalia have been mutilated because they are “slaves” in blackness, too. When has the sphinx ever had a home? What is her real secret? The monumentality of her survival, the blood of her past now “refined,” made white, built to crumble.

Photograph by J Grassi/Patrickmcmullan.com/AP.