AUGUST 28, 2013

50 Years Later:

Josephine Baker’s Speech at the

March on Washington Still Inspires

Bennetta Jules-Rosette was 14-years-old when she marched on Washington with her mother and father.

She remembers that it was so hot that day she could feel the heat from the pavement through the soles her shoes as she walked down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Her other memory is watching the performer Josephine Baker take the stage and deliver aspeech. Baker spoke about why she decided to move to France.

“I took the rocky path and tried to smooth it out a little,” said Baker, “I wanted to make it easier for you. I wanted you to have a chance at what I had.”

That speech changed the course of Jules-Rosette’s young life. A year later she found herself in France. She later went on to live there for many years and even became a dual citizen.

Jules-Rosette is now the director of the African & African-American Studies Research Center at the University of California–San Diego. She’s also the author of the author of “Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image.”

__________________________

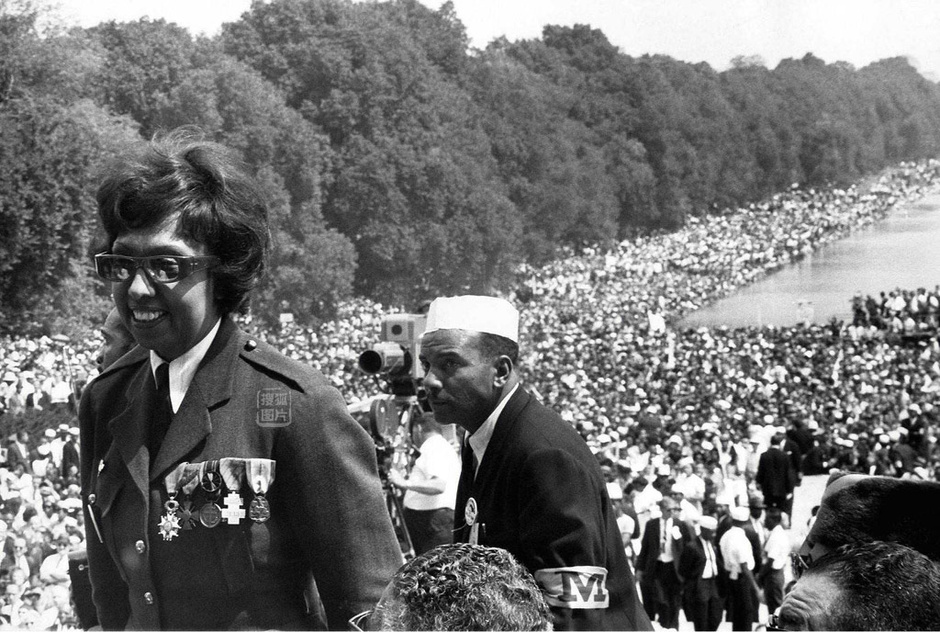

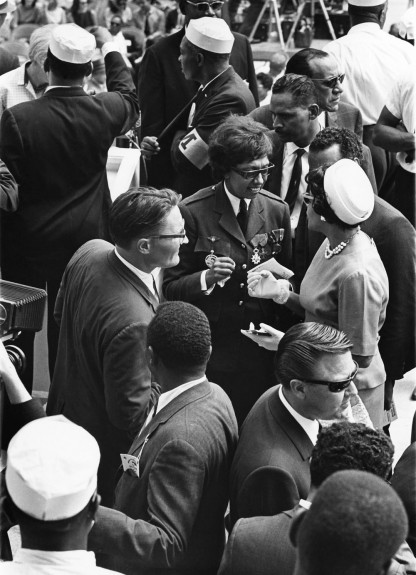

(1963) Josephine Baker, “Speech at the March on Washington”

Josephine Baker is remembered by most people as the flamboyant African American entertainer who earned fame and fortune in Paris in the 1920s. Yet through much of her later life, Baker became a vocal opponent of segregation and discrimination, often initiating one-woman protests against racial injustice. In 1963, at the age of 57, Baker flew in from France, her adopted homeland, to appear before the largest audience in her career, the 250,000 gathered at the March on Washington. Wearing her uniform of the French Resistance, of which she was active in World War II, she was the only woman to address the audience. What she said appears below.

Friends and family…you know I have lived a long time and I have come a long way. And you must know now that what I did, I did originally for myself. Then later, as these things began happening to me, I wondered if they were happening to you, and then I knew they must be. And I knew that you had no way to defend yourselves, as I had.

And as I continued to do the things I did, and to say the things I said, they began to beat me. Not beat me, mind you, with a club—but you know, I have seen that done too—but they beat me with their pens, with their writings. And friends, that is much worse.

When I was a child and they burned me out of my home, I was frightened and I ran away. Eventually I ran far away. It was to a place called France. Many of you have been there, and many have not. But I must tell you, ladies and gentlemen, in that country I never feared. It was like a fairyland place.

And I need not tell you that wonderful things happened to me there. Now I know that all you children don’t know who Josephine Baker is, but you ask Grandma and Grandpa and they will tell you. You know what they will say. “Why, she was a devil.” And you know something…why, they are right. I was too. I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America too.

But I must tell you, when I was young in Paris, strange things happened to me. And these things had never happened to me before. When I left St. Louis a long time ago, the conductor directed me to the last car. And you all know what that means.

But when I ran away, yes, when I ran away to another country, I didn’t have to do that. I could go into any restaurant I wanted to, and I could drink water anyplace I wanted to, and I didn’t have to go to a colored toilet either, and I have to tell you it was nice, and I got used to it, and I liked it, and I wasn’t afraid anymore that someone would shout at me and say, “Nigger, go to the end of the line.” But you know, I rarely ever used that word. You also know that it has been shouted at me many times.

So over there, far away, I was happy, and because I was happy I had some success, and you know that too.

Then after a long time, I came to America to be in a great show for Mr. Ziegfeld, and you know Josephine was happy. You know that. Because I wanted to tell everyone in my country about myself. I wanted to let everyone know that I made good, and you know too that that is only natural.

But on that great big beautiful ship, I had a bad experience. A very important star was to sit with me for dinner, and at the last moment I discovered she didn’t want to eat with a colored woman. I can tell you it was some blow.

And I won’t bother to mention her name, because it is not important, and anyway, now she is dead.

And when I got to New York way back then, I had other blows—when they would not let me check into the good hotels because I was colored, or eat in certain restaurants. And then I went to Atlanta, and it was a horror to me. And I said to myself, My God, I am Josephine, and if they do this to me, what do they do to the other people in America?

You know, friends, that I do not lie to you when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I cold not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ‘cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world.

So I did open my mouth, and you know I did scream, and when I demanded what I was supposed to have and what I was entitled to, they still would not give it to me.

So then they thought they could smear me, and the best way to do that was to call me a communist. And you know, too, what that meant. Those were dreaded words in those days, and I want to tell you also that I was hounded by the government agencies in America, and there was never one ounce of proof that I was a communist. But they were mad. They were mad because I told the truth. And the truth was that all I wanted was a cup of coffee. But I wanted that cup of coffee where I wanted to drink it, and I had the money to pay for it, so why shouldn’t I have it where I wanted it?

Friends and brothers and sisters, that is how it went. And when I screamed loud enough, they started to open that door just a little bit, and we all started to be able to squeeze through it. Not just the colored people, but the others as well, the other minorities too, the Orientals, and the Mexicans, and the Indians, both those here in the United States and those from India.

Now I am not going to stand in front of all of you today and take credit for what is happening now. I cannot do that. But I want to take credit for telling you how to do the same thing, and when you scream, friends, I know you will be heard. And you will be heard now.

But you young people must do one thing, and I know you have heard this story a thousand times from your mothers and fathers, like I did from my mama. I didn’t take her advice. But I accomplished the same in another fashion. You must get an education. You must go to school, and you must learn to protect yourself. And you must learn to protect yourself with the pen, and not the gun. Then you can answer them, and I can tell you—and I don’t want to sound corny—but friends, the pen really is mightier than the sword.

I am not a young woman now, friends. My life is behind me. There is not too much fire burning inside me. And before it goes out, I want you to use what is left to light that fire in you. So that you can carry on, and so that you can do those things that I have done. Then, when my fires have burned out, and I go where we all go someday, I can be happy.

You know I have always taken the rocky path. I never took the easy one, but as I get older, and as I knew I had the power and the strength, I took that rocky path, and I tried to smooth it out a little. I wanted to make it easier for you. I want you to have a chance at what I had. But I do not want you to have to run away to get it. And mothers and fathers, if it is too late for you, think of your children. Make it safe here so they do mot have to run away, for I want for you and your children what I had.

Ladies and gentlemen, my friends and family, I have just been handed a little note, as you probably say. It is an invitation to visit the President of the United States in his home, the White House.

I am greatly honored. But I must tell you that a colored woman—or, as you say it here in America, a black woman—is not going there. It is a woman. It is Josephine Baker.

This is a great honor for me. Someday I want you children out there to have that great honor too. And we know that that time is not someday. We know that that time is now.

I thank you, and may god bless you. And may He continue to bless you long after I am gone.

Sources:

Stephen Papich, Remembering Josephine (New York: The Bobbs-Mererill Company, Inc.: 1976), 210-213.

__________________________

August 23, 2011

March on Washington

had one female speaker:

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker is perhaps best remembered as a glamorous showgirl in 1920s and ’30s Paris who mothballed her skimpy costumes to serve in the French Resistance before becoming an international superstar. She was also the only woman to speak at the March on Washington.

Wearing her Free French uniform with her Legion of Honor decoration, the 57-year-old Baker had flown in from France, her adopted homeland, for the occasion. She had not been wanted at the event by all of its organizers, several of whom thought the girl from St. Louis had become a woman of France, out of touch with U.S. civil rights issues. But Baker was friendly with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and her managers worked to get her on the program.

Baker, who left school in sixth grade, was not entirely comfortable speaking publicly. Her speech relied on simple language, her presentation on her innate charisma.

And yet, there is something enchanting about Baker’s speech, about her oft-repeated life story: a poor, segregated childhood; an escape to France where race relations were years ahead of those in the United States; her adoption of the “Rainbow Tribe,” a social project/family of a dozen ethnically diverse children. She spoke for 20 minutes.

Bennetta Jules-Rosette was 14 when she attended the march with her parents. They moved with the masses down Pennsylvania Avenue on that “scorching hot” August day. “It was so hot,” she remembered. “The heat went through my shoes, up from the asphalt.”

Jules-Rosette, a professor and the director of the African & African-American Studies Research Center at the University of California at San Diego, wrote the biography “Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image,” in which she quotes from Baker’s speech.

“Friends and family,” Baker began. “You know I have lived a long time and I have come a long way. . . .

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ’cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world. . . .

“I am not a young woman now, friends. My life is behind me. There is not too much fire burning inside me. And before it goes out, I want you to use what is left to light the fire in you.”

Jules-Rosette recalled how inspired she was by Baker’s words, so much so that she followed Baker’s trajectory, traveled to France and became a dual citizen.

Baker wrote to King after the march: “I was so happy to have been united with all of you on our great historical day. I repeat that you are really a great, great leader and if you need me I will always be at your disposition because we have come a long way but still have a way to go.” She signed the Aug. 31 letter, “Your great admirer and sister in battle.”

King replied in November, telling Baker: “We were all inspired by your presence at the March on Washington. I am deeply moved by the fact that you would fly such a long distance to participate in that momentous event. . . . You are certainly doing a most dedicated service for mankind. Your genuine good will, your deep humanitarian concern, and your unswerving devotion to the cause of freedom and human dignity will remain an inspiration to generations yet unborn.”

Baker’s speech, Jules-Rosette said, is the sort of powerful prose that catches you by surprise. “When it’s read out loud, it’s really a performance piece,” she said. “I cry almost every time I hear it.”

Correspondence between King and Baker courtesy of the King estate and the Jean-Claude Baker Foundation.

***

MORE: For those who were there, memories of the March on Washington still linger

FULL COVERAGE: Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial opening, events, photos and videos