LOVE AND LIBERATION:

Sonia Sanchez’s Literary Uses of Personal Pain

Today. My simple passion is to write our names in history and walk in the light that is woman. — Sonia Sanchez [WF 30]

Introduction.

Although Sonia Sanchez has been publishing since the mid-sixties, there has been no diminishing of her poetic powers as she has aged; in fact, the exact opposite is the case–the poetry in her first book, Homecoming (1969), is no match for the brilliance of homegirls & handgrenades (1984) and is but a flicker when compared to the incandescent intensity of Wounded in the House of a Friend (1995). Rather than a brief candle who burned lyrically for a few years and then immolated herself in either self-destructive behavior or a selling-out of her talents to produce pap in exchange for momentary popularity and/or pecuniary reward, Sanchez instead has been a consistently blossoming beacon, ever shinning and in fact glowing brighter and brighter, while lesser lights dimmed around her. Like Langston Hughes and fine wines, over the years turned to decades, Sanchez ripened and matured rather than atrophied and lost potency.

But her’s has been a hard won consistency. Life for Sanchez has been no crystal stair, particularly in her attempts to actualize a stable woman/man relationship. She has slipped and been tripped, fallen down and sometimes briefly been turned around, but she has never quit, never stopped climbing. Sanchez has, with a minimum of whining and with a courageousness and feistiness inversely proportioned to her diminutive body build, demonstrated a remarkable staying power, an archetypal persistence in embodying the advice the old folks constantly admonished: you just got to keep on keeping on–to keep on going despite whatever hardships and disappointments you suffer in your personal life.

Sonia Sanchez’s keeping on has produced a body of work terrible in its honesty about the joys and pains of her personal life as well as profound in the relevance that the lessons drawn from Sanchez’s bittersweet years impart to us. Chief among those lessons is a constant refutation of internalized oppression. While there is both greatness and suffering in Sanchez’s work, there is no tragedy in the classic sense of the individual suffering because of an alleged fatal flaw in their makeup. As Sanchez sagaciously points out, the majority of our suffering is because of man’s inhumanity to man–more specifically, Whites’ historic inhumanity to people of color and men’s general inhumanity to women.

Although a philosophical investigation of the relationship between suffering and art as illustrated by the work of Sonia Sanchez would be of major interest, my purpose here is much more specific. I intend to review Sonia Sanchez’s creative use of the personal pain which resulted from her attempts to actualize long term, intimate female/male relationships. Simultaneously, I will suggest how Sanchez’s work and the attitudes expressed In her work mirror what I propose are tenets of a dialectical African-American, African-derived life philosophy/worldview. I will also ascribe to her creative prose a privileged position in both Sanchez’s own body of work as well as within the context of 20th century American literature as a whole.

Background.

Born Wilsonia Benita Driver to Wilson L. and Lena Jones Driver on September 9, 1934 in Birmingham, Alabama (or “Bombingham” as she sometimes affectionately refers to her home town), Sonia Sanchez lived with her grandmother after Sanchez’s mother died when Sanchez was about six years old. She moved to Harlem, New York with her father when she was approximately nine years old. Sanchez spent her adolescent and young adult years in New York city where she graduated from Hunter College as a Political Science major in 1955.

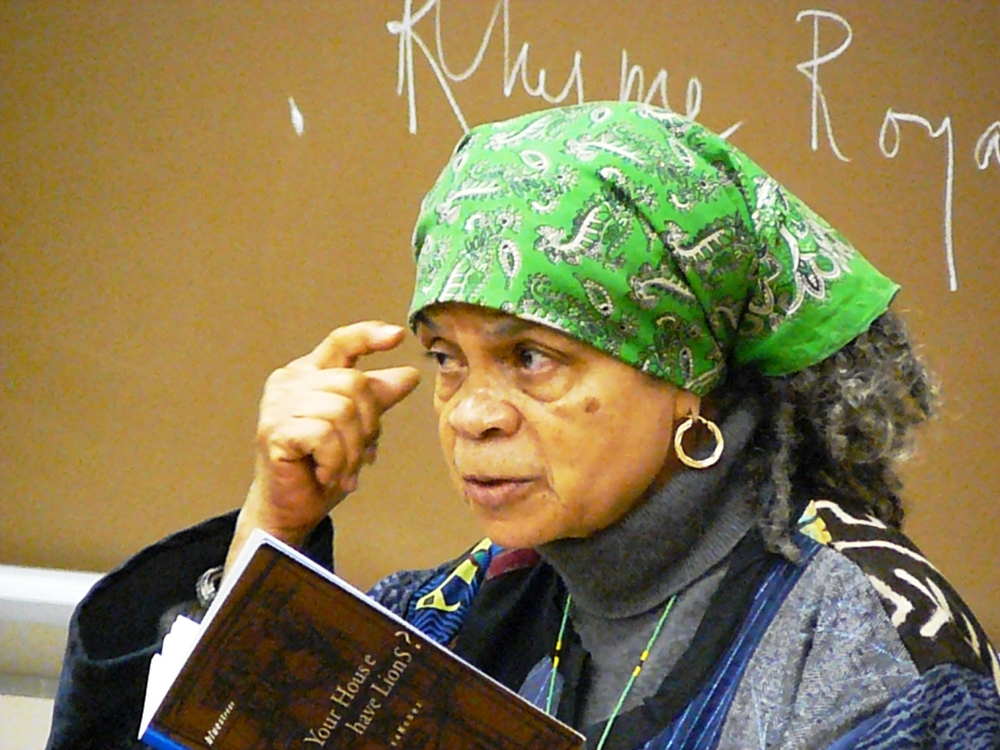

Teaching has comprised a significant aspect of Sanchez’s career. She has taught on the college level for many years, beginning with her stint at San Francisco State (1967-69) in the first Black Studies program under the directorship of Nathan Hare. Sanchez was chiefly responsible for bringing LeRoi Jones to San Francisco State as a writer in residence. Sanchez went on to teach at the University of Pittsburgh (1969-70), Rutgers University (1970-71), Manhattan Community College (1971-73) and Amherst College (1972-75). She is currently the Laura H. Carnell Professor of English, a chaired position at Temple University where she has taught since 1977. She has also taught in prisons, at libraries and in community workshops nationwide. Since the mid-sixties as both a writer and a teacher Sanchez has constantly been in the public eye.

Seeking Reciprocity: A Stutterer’s Articulate Battle Cry.

As a child Sanchez stuttered and as a result was very reticent about verbally expressing herself. She remembers herself as a shy and private child. That she has become an articulate, outgoing, engaging poet with the oratory power to move audiences to laughing out loud and to unashamedly crying in public is a direct reflection of Sanchez’s will to overcome. As her birth name implies: Wilsonia will sound on you. More than simply a survivor, Sanchez is a driver, a striver, always reaching for higher levels of consciousness and cultural expression. What is significant about Sanchez’s remaking of herself is that it was not simply an emotional remake, it was also a conscious intellectual remake. She read and studied as well as disciplined and forced herself to achieve. Because her impact is so overwhelmingly emotional, many people do not appreciate Sanchez’s philosophical depth, do not appreciate the rigorous intellect behind the visceral voice.

This privileging of the emotional and neglect of the rational is particularly emblematic of western man’s response to woman, regardless of the color of the man or of the woman. Men look at and react to Sanchez’s poetry (“did she cry?”) and react to the wetness of the emotions (“somehow she make you feel funny inside, almost like you too wants to cry!”), but to really consider what she is saying requires an acceptance of woman as mind, not only woman as fine (fine as in physically alluring, as in beautiful body).

What confuses some of us is that Sanchez never comes on like a brain, never resorts to coldly analytical language, never overcompensates in order to prove that she can think, never negates the emotional aspects of her being to demonstrate that she can fit into logic’s scheme. Even when in deepest thought she is always also feeling; always vibrant, coming from somewhere around the emotional equator (i.e. coming from where the sensuous sun do shine and the human temperament be warm). But just because she like to dance, don’t think you can walk all over her. Just cause she like to laugh, don’t think you can make fun of her. Just cause she woman, don’t think she can’t think.

But that is exactly what western man does. Relegates women to a world where logic doesn’t live, or if it lives, logic survives weakly and certainly doesn’t have much say so; as if feeling and logic were mutually exclusive–which they are not. What some critics have failed to consider is that there is a sensibility to Sanchez’s feelings; her emotions are reasoned and reasonable responses to and reflections on her life, a life that has been circumscribed by historic abduction, rape, and abandonment, and colored by specific male continuations of the historic and now canonical male-master/female-slave trope–a trope which has sexual abuse and sexual commodification at its core; a trope which suggests that man dominates woman and woman accepts being controlled; a trope which argues the essentialness of a male’s brutish nature and the inevitability of female hurt. This female-denigrating trope is precisely what Sanchez sees and rejects. Even as she personally experiences the pain filled reality of misogyny and patriarchy, Sanchez asserts that there is another way to live, to be/come. Thus, her words are both critique and battle plan. Her writings are no mere plea for individual sympathy, they are actually a cry of resistance, a call for rebellion against both the historic systemic and the specific individual abuse of Black women, or as she intones in her prayer/psalm Poem for July 4, 1994:

This is the time for the creative

Man. Woman. Who must decide

that She. He. Can live in peace.

Racial and sexual justice on

this earth.

[WF 60]

Sanchez challenges us to construct a humanity which, as she quotes Fanon, is “reciprocal.” Fanon’s quote at the end of Wounded is instructive because it identifies both the hope and the humanity of Sanchez’s vision. Fanon declared “I do battle for the creation of a human world–that is, a world of reciprocal recognition.” [WF 97] Imagine that this reciprocity is not just of White recognizing Black, but also of man recognizing woman. Further, imagine that this reciprocity is not just abstract, not just logical, but also experiential, also one that colors the reality of social relationships. This is what Sanchez is writing about. The search for that reciprocity is what her life has been about. The belief in the possibility of that reciprocity is one of the motivators sustaining her on this world’s lifelong battlefield.

In this short quote is summed up Sanchez’s worldview. First (“I do battle”), she is a warrior and privileges the necessity of struggle. Second (“for the creation”), she is clear that her objective is not destructive behavior but rather constructive behavior. Third (“of a human world”), she is not fighting for control of possessions but rather she is fighting to inaugurate relationships. Fanon/Sanchez are calling for a “human world” rather than merely “food, clothing, and shelter”–thereby defining world in social rather than material terms. Finally (“of reciprocal recognition”), she is definitive that relationships based on reciprocity determine what it means to be human.

Sanchez’s Fanonian worldview enables her to survive the corrosive reality of a personal life which might otherwise doom her to a cynical pessimism regarding the possibility of reciprocity between races and genders. Direct references to and quotes from Fanon are evident throughout her work beginning with her first book. Moreover, one of Sanchez’s poems from 1967 embodies the Fanonian dialectic between liberation and love.

After The Fifth Day

with you

i pressed the

rose you bought me

into one of fanon’s books.

it has no odor now.

but

i see you handing me a red

rose and i remember

my birth.

[LP 23]

This poem accurately mates Sanchez’s two major lifelong concerns and objectives. That the rose, a symbol of love, is placed inside a Fanon book demonstrates the centrality of both liberation and love for Sanchez. Indeed, Sanchez’s heart is in the struggle, and, as Che Guevera made clear in his famous quote (“Let me say, at the risk of seeming ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.”), liberation (which Fanon’s book symbolizes) necessarily contains and is motivated by love. Therefore, we can surmise that Sanchez loves liberation and that for Sanchez liberation is the best context for the preservation of love. Moreover, any analysis of Sanchez’s creative work, especially one which focuses on her intimate personal life, must be framed within the context of the larger quest for liberation, hence the trope of the rose preserved within the pages of a Fanon book. If not approached in this way, Sanchez’s personal life might be inaccurately construed as just another verse in the quasi-tragic “woe is me/another woman who been done wrong” soap opera/talk show melodrama rather than as a prime example of an ennobling and unending quest for human liberation and love. Time and time again, throughout Sanchez’s work, this liberation/love dyad of essential concerns remains constant at the core of every word she writes.

Although Sanchez has spent her entire adult life working as a professional, a college professor, she has never identified with the petit bourgeois or become an aspirant bourgeoisie. When we examine the people and struggles, the classes and social constructs that Sanchez writes about, we find that the majority of her characters are people who are either working-class poor or are activists/artists, or both. Sanchez’s ethnic/gender/&class-conscious work proffers a significant alternative to the conventional academic poetic concern with the atomized individual, i.e. the individual considered apart from their social background; their class, gender and political outlooks and aspirations.

While Sanchez is constantly writing about her personal life, she never writes from the perspective of navel gazing nor do we perceive Sanchez as being narcissistic, instead, Sanchez promotes comradery and makes one feel she is not only sharing experiences and insights but also, by revealing her own situation, she is declaring that I am in the same boat as you; I struggle and suffer the way you do, feel the same joys and pains you experience.

Fanon believed in the ability of the wretched of the earth to rise above. Fanon defined the wretched as the peasants of non-industrial societies and the proletariat of industrial societies within the context of the so-called third world–this was Fanon’s mating of class struggle with anti-White supremacy struggles. Further, Fanon identified the petit bourgeoisie as caught in the middle and forced to choose to identify with the wretched or the exploiters. Fanon believed that the professional classes would vacillate in allegiance to and identification with the wretched versus the exploiters. Significantly, Sanchez made her choice shortly after graduating from college and has remained constant in her allegiance to and identification with the wretched. Concerns about tenure, promotions, awards, material acquisitions and other trappings of professional success do not tattoo the body of Sanchez’s creative work.

Although she has gone through numerous job related confrontations and situations, it is noteworthy that Sanchez has chosen to focus on those aspects of her life that are most in common with her chosen audience of working class and activist readers/listeners rather than those aspects which seperate her from that audience and more closely align her with those who would psychologically and/or philosophically assimilate into the American mainstream. While I do not argue that Sanchez’s, or anyone else’s, professional concerns are irrelevant, we can not overlook that those concerns are not featured in Sanchez’s body of creative work. My point is to note the range of Sanchez’s selection of subject matter and to underscore her emphasis on themes of working class-oriented struggles to secure love and liberation on the one hand and her de-emphasis of professionally-related themes of integration into the status quo on the other hand.

When Sanchez does write about “buppies” (young Black professionals) and the “upwardly mobile” it is with a critical assessment of their life styles and aspirations, particularly their pursuit of materialism and the morality they exhibit (or more likely, don’t exhibit) in their quest to be accepted and to become like the maintainers and controllers of the status quo. Sanchez is more likely to write about the homeless than about suburban homeowners, about the unemployed rather than corporate executives, about women struggling for self-actualization rather than men ostentatiously displaying wealth. The people Sanchez chooses to celebrate by name are overwhelmingly either social activists or socially committed artists. This is another example of Sanchez’s grounding in a Fanonian worldview.

Additionally, Sanchez does not engage in nostalgic sentimentalizing of her African heritage, nor a romanticizing of her African-American history. Although she does acknowledge her people’s traditional greatness, her focus is on the day to day struggle to regain the power to control the content and direction of our day to day lives. When you read or listen to Sonia Sanchez, you are not encased in fantasy, nor are you encouraged to escape reality, rather we are inspired to recognize, struggle with and ultimately change reality. Part of the reason Sanchez’s poetry moves people is because that is Sanchez’s overt intent, i.e. to literally “to move” people to action. The success of Sanchez’s craft is that after experiencing her work, whether we agree or disagree with the content of her work, we are in fact moved by the emotional impact of Sanchez’s writings and presentations.

Sanchez’s Fanonian worldview and her particular gender and social concerns have not only informed the content of her creative work, her philosophy and her social practice (i.e. her personal praxis), Sanchez’s worldview has also helped shape the style and structure of her writings. The majority of her work is not intellectually oriented. Even though she has studied and understands world literature, Sanchez is not trying to prove that she has mastered conventional literature, therefore she is not trying to appeal to the heads of the professional class, rather her appeal is directed to the hearts and guts of the working class. This results in poetry and prose that is direct, often even didactic, in style. Although some of Sanchez’s work is slippery because it is allusive in imagery and elusive in meaning, even in those cases, she eschews the use of obscure and difficult intellectualisms. Usually the pieces which are ambiguous or difficult to grasp, are so not because they are over the reader’s head but rather because those pieces are very personal and sometimes require knowledge of Sanchez’s intimate life to be fully appreciated.

In any case, Sanchez’s Fanonian identification means that she wants the bulk of her published work to be understood by specific groupings of people and therefore she tailors her work to their sensibilities in language, in imagery, in structure, in performance. Language, in particular, identifies Sanchez not only with working people through her upholding of the vernacular as her language of choice, she also utilizes the raw immediacy of “cursing” and “common language” to attack upperclass pretensions, evasions, elisions and dissemling (generally manifested by the employ of euphemisms, especially for body parts and functions). From Homecoming to Wounded, Sanchez has neither desalinated nor cooled down her salty, pepperhot tongue as she continues to call things by their rightful name, whether the name be sweet loverman or worthless motherfucker. Sonia Sanchez talks shit, kicks butt and takes no prisoners. Teaching and/or critiquing the words and work of Sonia Sanchez requires at minimum a willingness to accept that the vernacular is a fit vehicle for creating the art of literature.

Class antagonisms notwithstanding, a positive critical reception of Sanchez’s work has steadily grown over the years mainly because of two factors: 1. Sanchez has constantly improved as a writer, and 2. there has been an across the board increase in gender concerns mated with a deepening/broadening of the class gap between the haves and have nots both within the race and between races. All of this has led to Sanchez standing at the forefront of socially committed writers. In a sense after nearly thirty years of constant work, Sanchez’s audience is beginning to catch up to her, beginning to understand and identify with her to the same degree that she understands and identifies with them. It is then, no surprise, that Sanchez not only continues to quote Fanon, but that almost thirty years after his death, Sanchez continues to use her own creative work to privilege the words and worldview of Frantz Fanon.

Understanding Fanon and his analysis is a seminal key to understanding Sonia Sanchez the artist/activist. The Fanon quote declaring advocacy of the battle to create a human world of reciprocity is taken from the last page of Wounded in the House of a Friend(1995). Sanchez’s first book was in 1969. She had a mighty long row to hoe between 1969 and 1995, a mighty long time to consider and reconsider her outlook on life. Throughout a long march which has included Black nationalism, pan-africanism, Black muslim membership, feminism, plus numerous personal battles on the social, economic and political fronts, throughout all of this, in addition to her unswerving commitment to struggle, Sanchez has been consistent in her championing of a Fanonian worldview.

Defining the Womanself.

In Homecoming, Sanchez’s poetic debut, amid fanged poetry which snarls at and attempts to bite the alabaster hand of racism, there are also the first inklings that Sanchez’s concern is with gender issues as well as race matters. The book ends with the short poem “personal letter no.2,” a gem of unsentimental self-definition:

but I am what I

am. woman. alone

amid all this noise.

[H 32]

Here, in a “personal” statement, Sanchez defines herself in terms of gender (“woman”) and social condition (“alone / amid all this noise.”). We are not told the specifics of the noise, but from the range of the twenty preceding poems we can surmise that the raucous din of racism and patriarchy are chief among the aural disturbances. While the racism is fairly easy to grasp, the gender oppression has often been overlooked even though Sanchez has been very clear in pointing out patriarchy’s perniciousness.

Throughout Homecoming, Sanchez directly addresses her brothers. She encourages (“this sister knows / and waits.” [H 10] or “here is my hand. / I am not afraid / of the night.” [H 11]); she cajoles (“don’t try none / of your jealous shit / with me. Don’t you / know where you / at?” [H 13]); and she criticizes (“and that so/ called/brother there / screwing u in tune to / fanon / and fanon / and fanon / ain’t no re / vo/lution/ / ary” [H 31]). Some of her observations may be appreciated simply as general political positions, but there are specific instances where there can be no mistaking that we are dealing not only with a general political position but also with a particular individual in pain. For example, how does one respond when Sanchez writes in “summary”:

is everybody happy?

this is a poem for me.

i am alone.

one night of words

will not change

all that.

[H 15]

Homecoming refers to returning to the ghetto (the segregated Black communities) after college graduation (“I have been a / way so long / once after college / I returned tourist / style to watch all / the niggers killing / themselves… now woman / I have returned” [H 9]). Notice that in this title poem which begins the volume, Sanchez defines herself (“now woman”) in precisely the same way that she does at the end of the book (“woman.”). Sanchez is telling us that her gender is definition and is both the beginning of her consciousness and literally the beginning of her adult life. Here her Blackness is presumed and articulated in the politics, but she specifies that which we might otherwise overlook.

Sanchez knows that we will not overlook her Blackness, and she insists that we not overlook her gender. Because Sanchez was so strongly race-oriented in her early work, regardless of how overt her specification of gender, some have indeed overlooked or minimalized Sanchez’s gender identification–she is seldom characterized as a feminist even though she specifically privileges her identity as woman as well as privileges the struggle to empower women as self-determining human beings. When we ignore the priority of Sanchez’s self-definition it means that we have not really seen or understood Sonia Sanchez.

Sanchez is so insistent on her identity as woman that if we have not seen it, if we do not recognize her inherent feminism, then it is because, like family members in denial, we choose to ignore whatever we are not prepared to deal with; this is especially true of Sanchez’s male readers. Thus, the full import of one of Sanchez’s most cutting and unsentimental love poems is dodged even as the poem is celebrated. short poem is perhaps the hardest hitting, and certainly one of the most quoted poems in Homecoming.

my old man

tells me I’m

so full of sweet

pussy he can

smell me coming.

Maybe

I

shd

bottle

it

and

sell it

when he goes.

[H 17]

The preposition (“when”) in the last line is the heart of the poem. Sanchez is not suggesting possibility–if she were, she would have used “if.” The poet is instead proposing inevitability (“when”). Here Sanchez is unequivocally stating her position: suffering loneliness at some point during one’s life is an almost inescapable aspect of social relations in America. Indeed, bouts with loneliness is a human fate which only a very few of us avoid.

Within a racist and sexist culture, it should be no surprise that Blacks and women are particularly susceptible to the social disruption of loneliness especially because they are both the victims of the society at large as well as the victims of their peers. The lower on the pecking order one goes (glibly but not wrongly defined as White Male / White Female / Black Male / Black Female), the more one is subjected to pecks from above. Since most social behavior is learned behavior shaped by one’s environment, then it is not surprising that the entity on the low end of the pecking order is the most alienated/oppressed and is also the most vested in the imperative to make change. The important point, however, is that loneliness–as well as other social ills–is not a racial or gender trait, but rather a human trait that can only be fully defined and understood within the specificity of its social context.

In America women do not suffer because they are women, rather they suffer because they live in a sexist society. One’s position in the pecking order is a major index of one’s susceptibility to becoming a social statistic of individual, ethnic or gender disorder; this is what accounts for the fact that being lonely and being a Black women seem to go together like white on rice–this is particularly true when we recognize that rice does not start off being white and it is in fact industry processing that “polishes” the color off of rice so that it appears white.

Once we recognize the seemingly unseverable linkage between being alone and being woman, then we understand that Sanchez’s pain is the female pain of a social being who is abandoned by a man/society who had pledged love but who failed to keep his/its promise. Note also that in this poem the man/society relates to the woman mainly on the physical level. This love/loneliness cycle is, in a nutshell, the basic outline of Sanchez’s life story of interpersonal relationships and though there are differences in details and particulars, Sanchez is nonetheless a representative member of the society which birthed, nurtured, oppressed, expolited and offers her both life and the imminent threat of death. Like all of us, Sanchez is both a respondent to and a creator of a myriad of complex social relationships and entanglements (some inherited, some selected, some imposed, some chosen). But through it all, she remains Black, woman and resistant to exploitation/oppression in both her personal and public life.

In all her subsequent books the basic paradigm (abduction/rape/abandonment) and resistance to that paradigm reign in her relationships with men (and society). So then, what is surprising is not the inevitability of “when he goes” but rather Sanchez’s forthrightness in documenting her hurt not in self pity but rather as instruction to her sisters and brothers, most of whom, to one degree or another, share her predicament; “sisters, watch out for this” and “brothers, don’t be this way.”

In candidly sharing her personal life, Sanchez crafts powerful poems, especially the short haiku which are so precise:

did ya ever cry

Black man, did ya ever cry

til you knocked all over?

[LP 35]

and

if I had known, if

i had known you, I would have

left my love at home.

[LP 50]

Notice that both of these are blues which use the AAB format of stating a line, repeating the line, and then responding with a closing line that qualifies, comments on, or expands the opening lines. An accurate close reading of Sanchez’s poetry requires an appreciation of Black music in general, and an appreciation of blues and jazz in particular. Moreover, a deep appreciation requires a working knowledge of the forms and techniques as well as knowledge of the history and personalities of Black music.

In this case, blues is relevant because blues has been our traditional form for commenting on interpersonal social relationships, especially problematic and/or unsuccessful relationships. A quick survey of Sanchez’s poetry will reveal her frequent use of blues forms and tropes even when, as is the case in the two poems cited above, Sanchez is working in poetic forms such as haiku and tanka, neither of which are African or African American in origin. Sanchez’s use of foreign poetic forms and especially her syncretic grafting of afrocentric musical forms as well as musical content onto those foreign poetic forms is the essence of Black postmodernism–the Black, cross-discipline, multi-cultural appropriation of all existing forms to innovatively produce new forms which reflect and contemporarize not only a Black aesthetic but which also offer example and paradigms that others may use to express themselves. In this regard, Sanchez’s technical prowess is a model of Black postmodernism.

However, Sanchez is not simply a harsh-noted, monotone militarist; she is also a lyricist who makes her work sing regardless of the theme. Her poetry is shaped by a fondness for nature metaphors and similes:

i saw you today

swaying like a lost flower

waiting to be plucked.

[LP 52]

and “your face like / summer lightning” [H&H 59]

and

my body is scarred

by your dry December tongue

i am word bitten

[WF 87]

Her lines are enlivened by brilliant usages of color: (“the pure / red noise of alone” [LP 45], “a green smell rigid as morning” [BB 45], “bright with orange smiles, may she walk” [IBW 99]).

Incisive wit and wordplay are her signature (“don’t play me no / righteous bros. / white people / ain’t rt bout nothing / no mo.” [H 26]

and

baby, you are sweet

as watermelon juice run/

ning down my wide lips.

[IBW 69]

and

never may my thirst

for freedom be appeased by

modern urinals.

[IBW 72]

The significance of these techniques is that they are employed to musical effect. Sanchez’s poems become songs, and because of the personal pain which predominates, many of her psalms are blues songs. This is the key to fully appreciating Sanchez’s poetry: the musical quality, a quality which is, of course, best experienced when the poetry is heard by the ear rather than solely looked at by the eye.

Abduction, rape, abandonment are the dominate notes in the blues scale of Sanchez’s early interpersonal poetry, and, to a more or lesser degree, these are the negative nodes of the majority of relationships experienced by Black women in America. In the context of Sanchez’s poetry and prose, these dominate notes have a meaning slightly altered from textbook definitions. Abduction refers to denying women their own space by placing them–through either guile or force–in spaces which the male controls. Rape refers to engaging in sexual relationships based on power rather than consent. Although some might find it a stretch to define infidelity as rape, however, when the male knowingly leads the woman to believe that she is engaged in a relationship of reciprocal love and he in fact does not honor the fidelity of that relationship, well then he has raped the woman and used the “force” of false promises (rather than physical brutality) to effect his will on the woman. Note that many women feel violated, used, “raped” once they find out that they are in a relationship where the man has consciously deceived them. Abandonment is the famous footsteps of the man walking away from a relationship when the woman confronts sexist behavior or when the man simply (and often unapologetically) tires of the relationship. Sanchez’s songs repeatedly delineate this triad of male-dominant/female-denigrated social realities.

A significant percentage of Sanchez’s poems either focus on or mention cross-gender relationships. For example, of 21 poems in her 1969 debut book, Homecoming, ten focus on personal relationships; of the 14 short poems which conclude her 1995 book, Wounded in the House of a Friend, eleven focus on personal relationships. Nearly every one of the 69 poems which make up the 1973 book Love Poems is focused on personal relationships. The nature and expression of interpersonal relationships, may, therefore, be seen as one of Sanchez’s major concerns. Although we are discussing, as Sanchez does also, mainly the downside, the painful side of personal relationships, we should note that Sanchez also is eloquent in presenting the joys and ecstacies of intimacy as exemplified by the poem black magic which is included in Homecoming:

magic

my man

is you

turning

my body into

a thousand

smiles.

black

magic is your

touch

making

me breathe.

[H 12-13]

The norm of poetry about personal relationships is a romanticizing of the desire for and the struggle to achieve fulfilling intimate unions. But rather than an ingenue cooing romantic pop tunes in search of Mr. Right, Sanchez is a classic blues diva shouting away her blues and concluding that what she really needs is to be in control of herself and her social relations:

i’ve been two men’s fool. a coupla black organization’s fool. if ima gonna be anyone else’s fool let me be my own fool for awhile,

[USS 99]

This self-assertive, self-affirmative blues-based outlook informs the bulk of Sanchez’s personal poetry. Yet as potent as Sanchez’s poetry is, there is another aspect of her work which supersedes her poetic achievements.

Her People’s Mighty Mouth

Although she is known primarily as a poet, Sanchez has made her strongest statements of personal hurt in prose. As illustration of this thesis, we will examine only three of a number of important prose pieces. The first is After Saturday Night Comes Sunday, the second is EYEWITNESS: CASE NO. 3456, and the third is Wounded in the House of a Friend.

My assessment that the prose pieces are stronger is based on what Sanchez has been able to achieve with prose as text in comparison to what she has achieved with poetry as text. Specifically, Sanchez’s prose evidences a number of important achievements, the most critical of which are: 1. Technical innovation, 2. Unflinching honesty, and 3. Emotional resonance. Technical innovation refers to Sanchez’s form and style of writing. Sanchez successfully moves inside our heads and hearts. She does not describe like a camera eye but instead she sounds. So rather than see, we feel; rather than make deductions about what she means based on what she shows us, we find ourselves actually experiencing with her the painful reality. Like music, we end up dancing and singing along notwithstanding that the song is often either a militant war chant opposing injustice or a deep bluesy moan figuring the wound of personal pain. Unflinching honesty refers to Sanchez’s use of her life as the example. Significant in this regard is that she manages to reveal so many particulars of her own life while honoring the privacy of those with whom she has interacted. Those who know her personally, know the names and ways of the men she writes about, know that Sanchez is revealing real wounds and not simply fictionalizing for art’s sake. Emotional resonance refers to Sanchez’s ability to make us feel intimately involved rather than stand back in aloof judgement.

The question of naming is particularly salient. In After Saturday… Sanchez used pseudonyms, in other prose pieces she uses first names and childhood nicknames, but in a number of the selections in Wounded, Sanchez consciously does not use any names. Through an unparalleled artistry, Sanchez gives us both intimacy and anonymity. We know the people, the situation, but we do not know the particular names, resultantly, whomever the cap fits is whom we think about. Given the modern American emphasis on the individual, Sanchez’s successful use of anonymity is even more extraordinary. But again, Sanchez is successfully leading us away from the tragic individual school of thought, into a more wholistic and communalistic approach to human behavior.

Moreover, as a consummate wordsmith, Sanchez stands on its head the writer’s axiom: show don’t tell–indeed, how can a memsmerizing storyteller not tell. The difference is the voice. When the telling is done in the socalled objective third person, it comes out standoffish like snow covered concrete on what ought to be a warm day, but when the telling be in somebody’s voice, especially a humor streaked, know what they talking about Black voice, well then it be like a handsewn comforter throwed up over you and your lover on a got nowhere else to be but in each other’s arms, middle of February, Saturday morn. The African-derived penchant is to use voice as an instrument of conjuring and this is what Sanchez does. As you read her, you hear her or her characters spelling their lives, loves, rememberances and aspirations into your being’s inner ear–the ear with which you hear and listen not only to what somebody says but also to the way they say what they got to say `cause that’s the only way you can get the fullest feeling for what they be meaning. “Show, don’t tell”–tell that to somebody else!

The privileging of the eye (i.e. showing) is a eurocentric/bourgeoisie philosophical approach. The privileging of the ear (i.e. telling) is an afrocentric/communal approach. Although this is not the occasion to detail the philosophical differences, I will offer this one example to illustrate the relevance of this observation to the realm of literature. Generally, reading a book is a solitary activity–one book, one reader. Moreover, the creator/writer of the book is not part of the process of the real-time reading experience of the auditor/reader’s decoding of the meaning of the book. However, if the book is read aloud, then immediately we have established a community, an exchange between the mouth of the reader and the ear of the listener (even if the mouth and the ear are part of the same body). In cultural terms, sound both requires and creates community; sight does not. Additionally, we experience sound by literally feeling the vibration on our ear drum, we use our physical bodies. Reading with the eye minimalizes the physical element. We are literally untouched by silent reading, and thus, what we feel is purely a matter of mentally decoded cues. But, sound, on the other hand, has a non-cognitive layer of meanings. Through sound, emotion is transmitted based on non-literal aspects. In addition to getting the literal meaning we also pick up the emotional meaning by interpreting the context, timbre, duration, inflection, and a host of other characteristics gleaned from how the word strikes us as it is sounded. None of this is directly connected to the literal “meaning” of a word. In fact, within the Black vernacular, the meaning of a given word might be reversed or be ambiguous until it is decoded on a non-literal level. The title of Sanchez’s second book, We A Baddddd People, is a prime example. In any case, I am arguing that “sounding” is essential to the art of Black literature, and that through “sounding” we can be lead to “feel” as well as “cognitively understand” a given situation, emotion, character, etc.

What Sanchez does with prose that she (nor anyone else) has been able to consistently master with poetry is figure out how to write down the musical qualities to such an extent that the reader is able to approximate the writer’s sounding of the piece simply by reading it aloud. I am suggesting that almost any literate person could effectively communicate the feeling of the prose by reading it aloud and that almost no one but Sanchez, or someone familiar with her presentation style and adept at performing poetry, could communicate the feeling of much of her poetry. I think part of this has to do with the fact that the poems are literally thematic sketches that are the basis of a presentation shaped by oral/aural improvisation. The prose, on the other hand, is a complex orchestration, a specific arrangement that is seldom altered during presentation–or certainly not altered to the extent that the poetry is. The best example of this is to contrast the EYEWITNESS: CASE NO. 3456 with Improvisation, both of which are in Wounded.

The printed poem Improvisation is actually a transcription of an improvisation between she and musician Khan Jamal. For the average person who has never heard Sanchez perform Improvisation, there is no way they would be able to read the piece aloud with any of the emotional resonance that Sanchez exhibited both in the initial performance and in subsequent readings. Perhaps a fellow performance poet or experienced actor adept at improv could fashion an arrangement which made sense and credibly sounded out Sanchez’s emotional intentions, but even the most adept would find this particular poem a bit difficult to communicate. EYEWITNESS, on the other hand, posses no such presentational problems. The average person would be able to communicate a great deal of the emotional impact suggested by the text of EYEWITNESS. I do not argue that the average reader would be able to match Sanchez’s presentation, but I do assert that they would be able to move the listening audience.

Sanchez’s singular achievement is in figuring out how to use words not merely to suggest sound but also how to use words to actually guide the reader in sounding the text. Indeed, to further drive home my point, I would suggest the following experiment. Type the text of both pieces into a computer equipped with text recognition software and set the computer to read back both pieces. There will literally be no comparison. Both in terms of meaning as well as emotion, the computer will be much more effective at rendering EYEWITNESS. On a technical level, Sanchez has figured out how to write prose that makes us both understand and feel rather than understand and infer.

Additionally, Sanchez writes so that we are made to both emotionally and cognitively comprehend how hurt deforms the human spirit, and this is, of course, no easy achievement. Many people write about pain in personal relationships, but most of the writing is pro forma and cliched, we’ve heard it all before and have no heartfelt emotional response. However, Sanchez essays unique takes on timeless themes.

I do not mean to imply that her poetry is second rate or that it is not innovative. But aside from her use of haiku and tanka forms–a use which has certainly inspired countless others to adopt these oriental poetic forms–Sanchez’s most unique and influential poetic achievements have been in the oral and aural rather than in the textual arenas. In fact, much of her poetry requires her performance for its fullest realization. The reader can not totally understand the impact and import of much of Sanchez’s poetry, until the reader literally becomes a listener.

Within the performance context, although Sanchez certainly had her own distinctive voice, her emphatic and effective use of sounding as the basis for realizing her poetry’s fullest potential is not a unique technique. Sanchez was but one of many dynamic poets of the Black Arts movement who literally ripped the poetry off the page and reinvigorated the artform by prioritizing sounding over literal writing. Amiri Baraka, Carolyn Rodgers, Nikki Giovanni, and Haki Madhubuti among many, many others, collectively reintroduced nommo–the African concept of the power of the spoken word.

Until one actually hears poems such as her early Coltrane influenced a/coltrane/poem, or the numerous poems which employ African chanting, Sanchez’s work on the page, especially her early poetry, does not overly impress in comparison to the textual verse produced by her peers and predecessors. Indeed, some academic critics, solely using conventional textual analysis theories and techniques, consider much of Sanchez’s early work under-realized as “quality” poetry. On the other hand, Sanchez’s prose has never been considered less than breathtaking.

Sanchez’s creative prose is startling in intensity and impact as text while simultaneously rhythmic and lyrical when recited as oration. In fact, literary critics such as Joyce Ann Joyce identify Sanchez’s prose as prose-poems, i.e. a mixture of the two forms. Sanchez has in fact done with prose what a generation of Black Arts writers did with poetry, she has made prose responsive to and reflective of the Black oral/aural traditions. The only precedent for her accomplishment is the prose of Jean Toomer’s Cane. But unlike Toomer, who was not able to duplicate his singular success, Sanchez has continued to develop and has boosted short, creative prose into heretofore unimagined realms.

At the core of Sanchez’s achievement is voice. She writes in a vernacular that “orates.” All of the creative prose pieces feature a voice, and most of them contain multiple voices. The use of multiple voices is another factor which distinguishes Sanchez’s prose from her poetry. The poetry generally presents only one voice. In Sanchez’s prose we hear an actual “we” rather than simply an “I” who identifies with “we.” In her prose our people talk, and thus we are given a sense of community.

As a rhetoritician of the Black experience Sanchez is peerless. In the seventies, Sanchez stylistically influenced countless Black female writers, Ntozake Shange chief among that number. This far ranging impact of her poetry notwithstanding, I nevertheless predict that Sanchez’s blunt albeit graceful and lyrical albeit deeply bluesy prose stylings will be her most remembered legacy. Shanchez’s prose is incandescent, and, in articulating the hard and lonely times of womanhood, she is a veritable Bessie Smith of literature–a poetic empress of the blues, a wordsmith of uncompromising power and importance. A mighty mouth. Her people’s voice.

Kicking The Habit Of A Love Jones

When After Saturday… was first published in Black World magazine I distinctly remember my numbed shock as I read the short story–it certainly was not fiction. Sanchez had recently married poet Ethridge Knight and had moved to Indianapolis. Could this be the story of their relationship–NO is what I wanted to say. YES is what the specifics of Sanchez’s words forced me to say. The stuttering. The writing out notes when she couldn’t talk. The twins. This was no made up tale about a sister struggling with a junkie, this was Sonia struggling with Ethridge, no matter that she had change the names to Sandy and Winston. Damn.

It had all started at the bank. She wuzn’t sure, but she thot it had. At that crowded bank where she had gone to clear up the mistaken notion that she wuz $300.00 overdrawn in her checking account.

[H&H 29]

That is the opening paragraph. Immediately we are offered a dramatic realization of the economic foundation of the relationship: Sandy makes the money, Winston takes the money. Initially Sandy blames the system (“mistaken notion”) but in this case, as we are shortly to experience, the fault was not caused by the system but rather by her man. Notice also that she has already personalized and defined the parameters (“her checking account”) of the theft; Winston is stealing directly from Sandy. When she is shown the canceled checks which indicate that there had been withdrawals from her account, Sandy reacts physically.

It wuz Winson’s signature. Her stomach jumped as she added and readded the figures. Finally she dropped the pen and looked up at the business/suited/man sitten across from her wid crossed legs and eyes. And as she called him faggot in her mind, watermelon tears gathered round her big eyes and she just sat.

[H&H 29]

The point of view and voice of the narrative is totally unconventional. Although the piece is written mainly in the conventional omniscient third person singular–the narrator informs the reader what the characters are thinking rather than merely showing the reader what the characters are doing–the twist is that this is not an objective voice of god (which is generally de facto a eurocentric, male voice). Sanchez’s voice is Black–hence the use of “dialect” as exemplified by not only the spelling but also by the imagery (“watermelon tears”). Although first person Black voices are not uncommon in literature, very few third person omniscient stories are narrated in a Black voice. Sanchez has introduced a significant breakthrough in privileging Black consciousness. And there is more.

Sanchez does not make traditional use of dialogue. There is no he said, she said. Instead we are given brief, sometimes double-voiced, monologues. The reader witnesses both the exterior and the interior voice, what the character says aloud and what the character thinks. Sanchez indicates this shift in point of view by using italics. There are no quotation marks. The overall effect is that the story is written in three points of view: the omniscient Black narrator, and the characters Sandy and Winston. Sanchez shifts effortlessly between the voices and does so with such clarity that we are never confused about who is “speaking” even when the voice shifts mid-paragraph, between one sentence and the next. The following example takes place after Sandy has returned home from the bank and Winston is talking to her attempting to explain what happened.

I can git clean, babee. I mean, I don’t have a long jones. I ain’t been on it too long. I can kick now. Tomorrow. You just say it. Give me the word/sign that you understand, forgive me for being one big asshole and I’ll start kicking tomorrow. For you babee. I know I been laying some heavy stuff on you. Spending money we ain’t even got–I’ll git a job too next week–staying out all the time. Hitting you fo telling me the truth `bout myself. My actions. Babee, it’s you I love in spite of my crazy actions. It’s you I love… You the best thing that ever happened to me in all of my 38 years and I’ll take better care of you. Say something Sandy. Say you understand it all. Say you forgive me. At least that, babee.

He raised her head from the couch and kissed her. It was a short cooling kiss. Not warm. Not long. A binding kiss. She opened her eyes and looked at him, and the bare room that somehow now complemented their lives, and she started to cry again. And as he grabbed her and rocked her, she spoke fo the first time since she had told that wite/collar/man in the bank that the bank was wrong.

The-the-the-the bab-bab-bab-ies. Ar-ar-ar-are th-th-th-they o-o-okay? Oh my god. I’m stuttering. Stuttering, she thot. Just like when I wuz little. Stop talking. Stop talking girl. Write what you have to say. Just like you used to when you wuz little and you got tired of people staring at you while you pushed words out of an unaccommodating mouth. Yeh. That was it, she thot. Stop talking and write what you have to say. Nod yo/head to all this madness. But rest yo/head and use yo/hands till you git it all straight again.

[H&H 30]

There we have three different voices–the third paragraph even mixes two different voices–yet the narrative is never jumbled, never impenetrable. Sanchez’s command of prose is miraculous and exemplary, especially so because technically she is taking huge risks that could easily come off as gimmicky or artificial and thus would alienate the reader when the subject matter literally cries for empathy.

Were this the only example of Sanchez’s prose skill we could pass off her achievement as luck, but, as we will see with the two prose selections from Wounded, Sanchez has mastered mixed voices and points of view. If only for her technical mastery, she should be lauded as a major writer of the 20th century–but, of course, there is more.

The honesty of After Saturday… is not simply in the concordance of what Sanchez writes with the actualities of her personal life. The honesty is in the fullness of Sanchez’s presentation, a non-sentimental though nonetheless human presentation of contradictions rather than a tunnel visioned and ultimately false one-sided interpretation. Sanchez’s prose is non-sentimental because she does not give us false hopes or storybook optimism. It is human because Sanchez renders the full and therefore necessarily contradictory range of her characters’ experiences, experiences that are sometimes awful and sometimes awe-filled. Sanchez’s emphasis is on survival and overcoming rather than succumbing to systemic oppression but she is not dealing with mythic personalities. Sanchez follows the admonition of sixties African liberation leader, Amilcar Cabral, who urged his comrades to “Mask no difficulties. Tell no lies. Claim no easy victories.” And that is both the beauty and strength of Sanchez’s refusal to tell the lie that love conquerors all. Rather than the television shibboleth: “don’t try this at home,” Sanchez goal is precisely to give us instructions for home use, thus, Sanchez prepares us to face reality by emphasizing what really happened rather than inducing us into a fantasy world of what she or we ideally/romantically may want to happen.

Sandy loves Winston. Even after she has been economically raped, she is willing to forgive and to help him kick his drug habit. (By the way–and although this is not one of the themes we are focusing on, I will mention it in passing–the debilitating effect of drugs is a major concern in Sanchez’s work whether she is remembering former high school classmates who succumbed, their beauty and talent destroyed, and, in some cases, their lives also destroyed; or whether recounting, as she does in Saturday, her own tussles with junkies who were also lovers; or whether looking at heart-renting scenarios as she does in Poem for Some Women which details a crack addicted mother leaving her seven year old daughter to be raped in exchange for drugs.) What is significant is that rather than showing us love conquering all, Sanchez prepares us for protracted struggle by boldly delineating the deep disappointments we will inevitably encounter in life.

Winston responds to Sandy’s attempt to help him kick by trying to persuade her to take drugs, and when that fails by stealing money from her again before abandoning Sandy and the twins. But, rather than end on the deathly downbeat of a ruptured relationship, Sanchez adopts the African worldview that death is not an end in itself because rebirth inevitably follows death. Thus, Sanchez’s story does not conclude with Winston’s abandonment on Saturday night but rather with Sandy’s rebirth/resurrection on Sunday morning.

She ran down the stairs and turned on the lights. He was gone. She saw her purse on the couch. Her wallet wuz empty. Nothing was left. She opened the door and went out on the porch, and she remembered the lights were on and that she was naked. But she stood for a moment looking out at the flat/Indianapolis/street and she stood and let the late/nite/air touch her body and she turned and went inside.

[H&H 35]

Which brings us to the issue of emotional resonance. Sanchez does not ask us to choose Sandy over Winston. In fact, Winston is portrayed as a victim of drugs who cannot control his actions although he desperately wants to kick his addiction. Sanchez is not a man hater, but she also is not a fool. Sanchez makes it clear that the Winstons of the world should be avoided and that simple one-on-one relationships will not save them from drugs. Sandy loves rather than hates Winston, but she recognizes that her love is not enough to save him or their relationship. Those who have had close encounters with drug addicts know that Sanchez has told the truth–love alone will not overcome addition. The emotional resonance comes from the accurate rendering of both the ups and downs, the sharply sounded conflicting and roller-coaster ride of inner emotions experienced by a person in love with a junkie, in love with someone whose drug dependency makes them physically and emotionally incapable of love.

She ran to him, threw her body against him and held on. She kissed him hard and moved her body `gainst him til he stopped and paid attention to her movements. They fell to the floor. She felt his weight on her as she moved and kissed him. She wuz feeling good and she cudn’t understand why he stopped. In the midst of pulling off her dress he stopped and took out a cigarette and lit it while she undressed to her bra and panties. …

It’s just, babee, that this stuff kills any desire for THAT! I mean, I want you and all that but I can’t quite git it up to perform. He lit another cigarette and sat up. Babee, you sho know how to pick `em. I mean, wuz you born under an unlucky star or sumthin’? First, you had a niguh who preferred a rich/wite/woman to you and Blackness. Now you have a junkie who can’t even satisfy you when you need satisfying. And his laugh wuz harsh as he sed again, You sho know how to pick `em, lady. She didn’t know what else to do so she smiled a nervous smile that made her feel, remember times when she wuz little and she had stuttered thru a sentence and the listener had acknowledged her accomplishment wid a smile and all she cud do was smile back.

[H&H 33]

At one time or another many of us have smiled at our own wretchedness as we were overcome by a situation we helped create but which we did not desire–the “got what you wanted but don’t want what you got” syndrome. As Winston laughs harshly and Sandy smiles resignedly, we are able to empathize with Sandy even if we have never been in her particular predicament, even if we are not a woman hooked up with a junkie. Sanchez achieves this emotional resonance not because of the horror of the tale but rather because of the vulnerability of Sandy’s smile. A writer has to work hard to realize such emotional moments. No matter if she is recalling a specific incident, the craft is still in the selection of specifics, the insight to realize that Sandy’s smile is the most important image in this particular passage.

Sandy’s tale is replete with these vulnerable moments, vulnerabilities which, under varying circumstances, all humans have felt. Another example of emotional resonance is Sandy’s moment of self doubt.

When she came back up to the room he sed he was cold, so she got another blanket for him. He wuz still cold, so she took off her clothes and got under the covers wid him and rubbed her body against him. She wuz scared. She started to sing a Billie Holiday song. Yeh. God bless the child that’s got his own. She cried in between the lyrics as she felt his big frame trembling and heaving. Oh god, she thot, am I doing the right thing?

[H&H 35]

Who has not thought that thought at one time or another? The smile, the question, those are the resonant hooks that help the reader not simply sympathize with Sandy’s predicament, those are the resonances that set off sympathetic vibrations within each reader regardless of our race, gender or social condition. And that is Sanchez’s achievement as a writer, that is the difference between an artist and a reporter, between someone with a finely tuned inner ear and someone with only a videocam eye who nonemotionally spies the externals. Sanchez successfully pierces the facade of appearances to present us with the internal emotions and rationalizations which accompany the actions. Sanchez is adept at identifying the underlying basic human emotions bubbling just beneath the surface of these particular and highly specific individual clashes and encounters.

Your Best Friend Could Be Your Worst Enemy

In Wounded… Sanchez flirts with cynicism and pessimism regarding intimate relations with men. Listen to the female palaver of blues haiku 1:

all this talk bout love

girl, where you been all your life?

ain’t no man can love.

[WF 82]

The insertion of “girl” suggests that this is one woman talking to another, certainly the poem is not addressed to men even though it is about men. The poem could be read as Sanchez’s advice to women, or it could be read as a woman friend attempting to school Sanchez. In any case, the poem represents thoughts at a midnight hour, when the disappointing day has been so long, the lonely night even longer, and the dawn is a long, long ways off–possibly even too long a ways away to be endured.

One might suppose that Sanchez had drowned in this poem’s funk were it not for the fact that Wounded both opens and concludes with quotes from Fanon. The opening quote is prophetic: “I have only one solution: to rise above this absurd drama that others have staged around me.” [WF 1] Again, we witness the worldview that locates the fault not in the gods or in the stars but rather in the “absurd drama that others have staged around me.” Sanchez is clear, no matter how menacing the forces arrayed against her, no matter how debilitating the betrayals, she as individual is not essentially flawed and she can overcome, she can “rise above.” Likewise, the book concludes with a quote which starts with three assertive and affirmative words: “I do battle.” To rise above. I do battle. Those are not victim sentiments, those are warrior chants, wild woman anthems.

Because she is human like all of us, Sanchez has her moments of weakness and self pity, or as she asked in I’ve Been A Woman:

what is it about

me that I claim all the wrong

lives, the same endings?

[IBW 80]

The key is not in denying such moments, but rather in acknowledging them and then moving on, continuing to rise above, continuing to do battle. Sanchez is no one dimensional writer, no heroic goddess. No. She is what we all are: human and subject to hurt, disappointment and even moments of despair, as well as, at her (and our) best, we/she is an agent of resistance and change who willingly embraces the eternal struggle to make life better and more beautiful, the ongoing and seemingly endless rolling of the rock of salvational humanness up the mountain of social and personal contradictions, consciously engaging in the lifelong contest to make this world human.

Were it not for this bedrock foundational faith in herself and humanity, Wounded would be too terrible to bear. This book is Sanchez’s most brutal and unsparing; it is also her most daring and most accomplished.

We are discussing Sanchez’s use of personal pain and heretofore we have assumed that personal meant autobiographical in the strict sense of the word. But Wounded offers us something more challenging. Just as Sanchez implicitly asks readers to identify with her personal life, Sanchez also identifies with the personal life of others, and in so doing expands the parameters of personal. Moreover, Sanchez chooses to identify with wretchedness and self-abasement, and not just with (s)heroism and self-actualization. So while there are tributes and celebratory poems/prose pieces for Spelman College grads and college president Johnetta Cole, for sister writer Toni Morrison and for socially-committed singing group Sweet Honey In The Rock, for James Baldwin and for President Vaclav Havel, and for Essence magazine and free Nicaragua, there are also tough, tough pieces which articulate voices many of us would really prefer not to hear.

Voices such as the young woman who orally-sexed Tupac Shakur on a dance floor:

Like

All i did was

go down on him

in the middle of

the dance floor

…cuz he’s in the movies on the

big screen bigger than life

bigger than all of my

hollywood dreams

cuz see

i need to have my say

among all the unsaid

lives i deal with.

[WF 67 & 68]

Voices such as the aforementioned crack-addicted mother who deposits her seven year old into the clutches of monstrous males who repeatedly rape the little girl

and so i took her to the

crack house where this

man. This dog this

former friend of mine lived

wdn’t give me no crack

no action. Even when

i opened my thighs to give him some

him again for the umpteenth

time he sd no all

the while looking at

my baby my pretty

little baby. And he

said I want her. i need

a virgin. Your pussy’s

too loose you had

so much traffic up

yo pussy you could

park a truck up there

and still have room

for something else.

And he laughed this long laugh.

And I looked at him and the

stuff he wuz holding in his

hand and you know i cdn’t

remember my baby’s

name he held the stuff out

to me and i cdn’t remember

her birthdate i cdn’t remember

my daughter’s face. And

i cried as i walked out that door.

[WF 72]

Perhaps the most troubling voice is the valiant voice of a rape survivor who courageously refuses the false shelter of silence.

i was raped at 3 o’clock one morning…

And then he tore off my gown and pushed my legs up and went inside me. He was soft. i thought, this won’t hurt too much. Then he screamed, move yo ass bitch cmon move yo ass with me you know you want this yeah that’s it move yo ass i’m gon give you a fuck like you ain’t never had and as he talked he got harder and harder and he jabbed his penis from one side to another up against my fibroids and i screamed and he socked me, said, start talking bitch say it’s good it feels good tell me how juicy it is tell me how you love the pain go on talk to me bout big black dicks and sucking big black dicks yeh here i come with mine cmon suck me off cmon lick him suck him feel my balls. . . . Ahhhh yes yess. Smile bitch this here’s mo fucking you’ve had in a long time. Go on suck him hard that’s it oh that’s it keep him hard cuz he gon rip you up inside. Turn over yeh turn over i want to see what you got back there.

And i screamed O my God no don’t. Don’t. And he hit me in the head pushed my mouth flat down on the bed. i cdn’t breathe. i thought i would suffocate then and there and he pulled my head up and whispered in my ear don’t mess with me bitch. Push yo ass up and enjoy. . . .

[WF 69-70]

All three of these tough talkings by different women are in the first person. Does it mean that Sonia was addicted to wild sex, to crack, does it mean she was a rape victim (some questions we dare not ask because we really don’t want to hear an affirmative answer)? But sister Sanchez is not letting us off so easily. Sanchez understands that if we are truly “we,” then we are all of us, each one of us is identified with every other one of us–and not just the best of us, but also the wretched of us. Sanchez understands that to embrace Fanon is to fully identify with the wretched of the earth, not merely in an abstract philosophical sense but also as a lived identification which accepts down in order to reach up.

Note Sanchez’s use of double voice in the rape piece, how she has fine tuned her technique so that she does not even need to use italics, she can shift voices within a sentence, and never once are we confused–dismayed, repulsed, angered, shamed, but never confused.

The construction of this short prose piece, aesthetically is an architectural marvel. Sanchez manages a near impossible feat: she simultaneously presents the voice of the rapist and the voice of his victim. This doubling of the first person point of view binds us even closer to what is happening. We are literally immersed in a negative union whose terror is more profoundly realized than if only one or the other were telling the story. Moreover, through the use of first person Sanchez has removed the distancing effect endemic to the use of the third person. This is one of the most harrowing texts on the rape theme ever written. There is no him and her for the reader to either condemn and/or identify with, there is only I and me. If one reads the piece aloud, what happens is that the reader becomes both parties in this assault. Moreover, although the opening establishes that the female is telling us about what happened to her, by presenting the rapist in the first person, Sanchez effectively disrupts a one-sided identification and forces us to participate in the actual rape. When you say the words aloud you become the rapist.

There is a musical analogue to this doubling of the first person: the amazing leaping of intervals between the extreme upper register and the extreme lower register which was pioneered by free jazz saxophonists such as John Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, and especially Eric Dolphy, all of whom are well known to Sanchez. I am not suggesting that she consciously copied (or more precisely “copped”) this technique from the musicians. Indeed, the musicians themselves were appropriating oratory techniques and injecting those techniques into instrumental music; they were literally making their horns talk, scream, sing, shout, wail, moan, etc. I believe that, within their respective disciplines, both the jazz musicians and Sanchez were making innovative use of the basic African derived cultural value of call and response, except rather than require an external audience, they fissured themselves, split one into two, and both issued the call and responded to the call. This is, of course, another instance of the principle of reciprocity at work, and reciprocity is itself a reflection of dialectics. So then, whether consciously or intuitively, Sanchez has disrupted non-dialectical linear progression with oscillating dialectical progression. This is the awesome achievement so brilliantly demonstrated in EYEWITNESS: CASE NO. 3456, Sanchez’s rape piece.

The “technical innovation/ unflinching honesty/emotional resonance” triad that we used to analyze After Saturday… is equally applicable to EYEWITNESS. We need not repeat the close reading to appreciate Sanchez’s mastery; anyone who has read EYEWITNESS and who understands the analytical approach presented here can do their own basic critique. I do however think it instructive to note Sanchez’s ongoing use of death/rebirth as a philosophical construct.

If we experience the rape as a slaughter, as the victim psychologically dying beneath an onslaught from above–including the forced internalizing of the instrument of one’s own destruction (oral sex: the literal ingesting of the rapist’s penis), then we can more clearly appreciate Sanchez’s use of the African rebirth-following-death belief system. We do not end with rape and the internalization of oppression, instead we end with survival and morning, living for a new day regardless of how terrible the night has been.

When I awoke in the morning he was gone. I dragged myself out of bed and looked under beds, inside closets under beds, inside other rooms, under beds, ran out of the house, to the porch, and felt the blood on my legs held the blood in my hand saw that the morning had returned and put on my face.

[WF 70]

This is the same way in which After Saturday… ended. I cannot overstress the philosophical importance of this “morning/rebirth” trope.

Although not as wrenching in its subject matter as EYEWITNESS, the title selection in Wounded is technically and emotionally one of the most complex tour de forces in Sanchez’s body of published work. Whereas EYEWITNESS and the other prose pieces maintain a chronological narrative with only one theme and a limited well defined range of emotions and reasonings, Wounded knots together the diverse threads of 1. infidelity, 2. attempts at reconciliation, and 3. desperate acts to sometimes face and sometimes avoid the truth of a series of intimate encounters which take place over an unspecified time period. Sanchez does not use a neat and easily followed chronological narrative, nor does the story focus solely on one event or issue, and certainly there is no clear demarcation of emotions or reasonings, Wounded… is instead a tempestuous and disorienting experience which totters back and forth between tragedy and comedy, cool calculations and frantic reactions. As the marriage disintegrates, the narrative gathers up and ties together the resulting sadness and pathology into an intricately interwoven burial shroud which is used to wrap the remains of an intimate relationship gone to rot.

Some pains cannot be borne in silence. Some pains can not be locked out of sight. They are too huge to carry alone. And thus Sanchez has vomited forth Wounded, and what a regurgitation of pain this prose piece is.

Again there are multiple voices (male, female, and Black third person omniscient) orchestrated into a tapestry of intrigue and resentment. As the relationship lurches totally awry, we understand how unhappy they are making each other, yet neither can stop–the behavior has become compulsive. At some point, we wish that the unnamed “she” would have just put the philandering “him” out, but, no, instead she tries to pull him deeper in: two non-swimmers, pathetically flailing about as they drown in a sea of ersatz love. Witness–recall the use of nature images, the use of brilliant color, and the use of wordplay:

i am preparing for him to come home. i have exercised. Soaked in the tub. Scrubbed my body. Piled myself down. What a beautiful day it’s been. Warmer than usual. The cherry blossoms on the drive are blooming prematurely. The hibiscus are giving off a scent around the house. i have gotten drunk off the smell. So delicate. So sweet. So loving. i have been sleeping, no, daydreaming all day. Lounging inside my head. i am walking up this hill. The day is green. All green. Even the sky. i start to run down the hill and i take wing and begin to fly and the currents turn me upside down and i become young again childlike again ready to participate in all children’s games.

She’s fucking my brains out. I’m so tired i just want to put my head down at my desk. Just for a minute. What is wrong with her? For one whole month she’s turned to me every nite. Climbed on top of me. Put my dick inside her and become beautiful. Almost birdlike. She seemed to be flying as she rode me. Arms extended. Moving from side to side. But my God. Every night. She’s fucking my brains out. I can hardly see the morning and I’m beginning to hate the nite.

[WF 6]

Speaking to his friend Ted, the male mate denounces his partner’s attempt to bind up their wounded relationship with the gauze of unending sex:

It ain’t normal is it for a wife to fuck like she does. Is it man? It ain’t normal. Like it ain’t normal for a woman you’ve lived with for twenty years to act like this.

[WF 7]

By implication he is suggesting that his behavior is normal–his betrayal of their vows, his dalliances and debaucheries are all conduct befitting the male of the species, especially since he’s been with her “for twenty years.” This then is the bell that tolled the midnight hour and led to the sentiment that “ain’t no man can love.” Moreover, this is not a new thought, back in 1970 Sanchez said in Personal Letter No. 3:

it is a hard thing

to admit that

sometimes after midnight

i am tired

of it all.

[IBW 20]

In the middle of the narrative are two interrogations, both of which feature one-sided attempts to talk out the problem. Anyone who has been involved in a discussion to save a doomed relationship will surely recognize the gregarious eagerness of one party which is offset by the terse sullenness of the other party. Additionally, in Sanchez’s narrative the male is a lawyer, so the question/answer format has an additional layer of meaning. Sanchez balances the torment by switching the aggressive questioner and withdrawn respondent roles: first the woman questions and the man begrudgingly answers:

Do they have children?

one does.

Are they married?

one is.

They’re like you then.

yes.

How old are they?

thirty-two, thirty-three, thirty-four.

What do they do?

an accountant and two lawyers.

They’re like you then.

yes.

Do they make better love than I do?

i’m not answering that.

[WF 4-5]

and then it is the male’s turn to probe for understanding while the female smugly responds:

yes. but enough’s enough. you’re my wife. it’s

not normal to fuck as much as you do.

No?

can’t we go back a little, go back to our

normal life when you just wanted to sleep at

nite and make love every now and then? like me.

No.

what’s wrong with you. are you having a nervous

breakdown or somethin?

No.

[WF 8]

Regardless of who is questioning whom, however, the upshot of it all, of course, is that no matter how sincerely one party may approach the discussion, to the other party the discussion resembles an inquisition more than a conversation.

Moreover, Sanchez presents the female narrator with an unblinking honesty that helps us understand how it is that such a supposedly insightful and wise person can willingly drift so far away from dry land. Time and again, one of the first reactions exhibited by a rejected female is to question her self-worth: there must be something wrong with me:

As I drove home from the party i asked him what was wrong? What was bothering him? Were we okay? Would we make love tonite? Would we ever make love again? Did my breath stink? Was I too short? Too tall? Did i talk too much? Should i wear lipstick? Should i cut my hair? Let it grow? What did he want for dinner tomorrow nite? Was i driving too fast? Too slow? What is wrong man? He said i was always exaggerating. Imagining things. Always looking for trouble.

[WF 4]

Clearly, in loveland there are no exemptions for poets or anyone else–nor should there be. After all, the index of humanity is social intimacy; all of us are capable of being open and some of us are willing to keep our word, some of us do struggle to live up to the values we espouse. The reality is, however, that it is impossible to distinguish in advance the some who will struggle from the all are capable but for various reasons do not live up to their capacity. And then too, we all have our breaking points, and until we are put to the test we never really know what we will do when the pressure is on or when certain temptations are placed in our path. Regardless of contingencies, the hard fact is that you can’t swim in the sea of love without getting wet/hurt–if only momentarily.