TANYA TIET

Kalamu ya Salaam's information blog

TANYA TIET

INNA MODJA

Interview with Award Winning

Neo-Griot Kalamu ya Salaam

[Rudolph Lewis, publisher of Chicken Bones, interviews Kalamu ya Salaam circa 2003. The entire interview plus most of Kalamu’s writings referenced in the interview are available on Chicken Bones > http://www.nathanielturner.com/kalamuinterview.htm]

10

Yusef Komunyakaa & What Is Life?

Rudy: Who are your favorite contemporary poets? Could you tell us a bit about Kysha Brown?

Kalamu: Favorite contemporary poets. Answering that is a recipe for misunderstanding. I have friends. There are also people I would dig if I knew their work. There is so much going on that I dig, If I say four, I’ve got to say ten more, and then that is a hopeless question for me to answer. I could answer about my influences because I have gone back and examined my work and my influences. But there is so much happening today. I can’t possibly do justice to that question. I read a lot. A lot. I hear a lot. Travel a lot. Attend conferences, slams, open mics, lectures, readings, book signings. etc. Everything. I’m always digging the scene.

Kysha Brown. I met her in 1993–if I remember correctly. She is a founding member of NOMMO Literary Society (September 1995). She is my business partner in Runagate Press.

Rudy: There’s the contemporary poet Yusef Komunyakaa, the Pulitzer Prize winner who can be likened to a kind of black Ezra Pound. His poems have become more and more abstruse so that one needs an encyclopedia to understand his allusions. He’s teaching, I believe, at Princeton now, where Cornell took his retreat.

Yusef and I used to be close acquaintances back in the mid-80s. I learned a lot about poetry from him, for which I am thankful. Of course, we had our disagreements. He has a more conservative view of the social world than I. He was a military man; I was a draft resister and part of the black consciousness and labor movements. Have you ever included him in any of your anthologies? Have you reviewed his work? If not, why not? What do you think is the relevance of his work?

Kalamu: He is included in a new anthology I am working on. Yes, I have reviewed his work. I am particularly fond of Dien Cai Dau, his book of poetry about his Viet Nam experiences. As for the relevance of his work, what difference does it make what I think? I think he ought to do what he wants to do—if folk find something useful in what he does, good, if not, let it pass.

My philosophical view is embracement. You don’t try to put somebody out the family just cause you don’t like them. You don’t exclude some people just cause their work is not to your taste. If you don’t dig it, leave it on the table and move on. Yes, there are positions that Yusef takes that I disagree with, but there are positions that Kalamu took in the past that I disagree with today.

This goes back to the dualism and competitiveness question we talked about earlier. I think it’s beautiful that our people can produce both a Yusef and a Kalamu. And I think they are obviously different and that there are many points of divergence between them. Again to go to the music, it’s like we have Errol Garner on one hand and John Lewis on the other. Two pianists: Garner self taught and Lewis formally trained. The strength of jazz is that they could be contemporaries and both be respected for what they do even though their approaches to the music are literally worlds apart and seemingly antagonistic.

Please remember, the acceptance of, indeed, the promotion of diversity is an African trait. In New Orleans we have a song—”Do What You Wanna!” Diversity first. This does not mean that we pretend there are no differences, or that we do not argue for our point of view. Everybody knows that Kalamu got opinions and is not afraid to speak his mind. You don’t have to read much of my work before you see some hard lines drawn, but those are my lines, what I believe. Other people don’t have to agree with me in order for me to dig them or for them to dig me.

If you have a specific position that Yusef takes that you want me to comment on, I will do that. But even when I might strongly disagree with his position, I still embrace him as my brother and salute him as fellow poet and, to be clear, this is not about Yusef per se. Embracement, diversity, those are my philosophical positions in general with everyone. Of course, this is not a blind embracement nor a valueless espousal of diversity. My embracement of my enemies is struggle. My acceptance of diversity does not mean giving way to evil, to that which is anti-life. I will speak out against whatever I consider wrong.

On a national level my first publication was in Negro Digest as a critic. I was reviewing books. Over the years I have have published literally hundreds of reviews of books, records, concerts, events published. I won the first Black World’s first Richard Wright award for literary criticism. My critical work spans over thirty years of publishing. I have come to this position about criticism: I will only review what I like or think is valuable, what I think adds something to our culture. The only exception to that rule is if I think something is dangerous are particularly harmful, I will attack it. Otherwise, it’s live and let live. And I will specifically refrain from dissing something, just because I don’t like it. Within a workshop setting, I will offer my comments on what I perceive as the strengths and weaknesses of a given work, but I will not do so in general.

Without a communal setting the critical comments are often perceived solely as an attack, and often do more harm than any good. Again, we are dealing with African approach. The stronger the communal base, the sharper the criticism can be without doing harm. A strong community enables healthy criticism. But when there is no community, than the criticism usually does not come from a position of trying to help develop whatever is being criticized but rather comes from the position of putting it down. So if you are not in a position to help develop and you don’t perceive a real need to stop or oppose something, than there is no reason to criticize it. From my perspective the purpose of criticism is either to improve that which is being criticized or to defend the community from attack.

Rudy: Do you think that black women writers, especially those who are prose writers, have a greater audience than black male writers? If that is indeed the case, what is the cause of such a phenomenon?

Kalamu: I wrote about the public perception of black women writers in What Is Life? two important essays in that regard “If the Hat Don’t Fit, How Come We Wearing It” and Impotence Need Not Be Permanent. I stand by those statements.

Rudy: I am not familiar with either one of these pieces. Where can they be found? That raises another essential question. So much that is vital is now out of publication? Hasn’t that affected your own influence? Libraries seem to be only interested in the latest. You can imagine some of the black titled that libraries are weeding from their catalogs. I have a book of James Van DerZee that our local library sold for fifty cents. How do we deal with this problem of the control of information?

Kalamu: It is not a problem of control of information. It’s a problem of self-determination. As long as we are content to let others define our culture, our lives, well. As for where those pieces are found, it just so happens they are in one of my few books still in print, the collection of essays published by Third World Press, What Is Life?In fact, I think my responses to a lot of the questions you raise are spelled out in some detail in What Is Life? Maybe forty or fifty years after I’m gone, that book will stand as a statement on the tail end of the 20th century.

11

Cultural & Political Work

Rudy: What do you think is the dominant black cultural ethos today. You, I understand, are more drawn toward a “community ethos.” Is this related to the neo-griot movement?

Kalamu: Commercialization and apolitical creolization are the dominant cultural ethos today. Neo-griot is, hopefully, an alternative.

Rudy: Could you further explain what you mean by the expression “apolitical creolization”?

Kalamu: Creole refers to a mixture. Our integration into the American society is a process of creolization. If we are apolitical about it, then we accept the status quo definitions of economics, politics and ethics. If we were to politicize the process of creolization, we would at the very least argue for and fight for specific modes of social organization, of economic systems, of political systems. But, at this point, all we argue for is a bigger piece of the pie. That is what I mean by apolitical creolization.

Rudy: You have championed the recognition and maintenance of a separate and vibrant black identity. And through the various groups you have founded and motivated, you have increased international awareness of oppression. Is all of this activity related or connected to other domestic movements that are struggling for social justice in the USA?

Kalamu: I’m not sure that I understand this question. but I do emphasize internationalism, more so than domestic identification.

Rudy: I am not sure what you mean by “internationalism.” Marxists and communists used to speak of internationalism. I know that you are neither. It doesn’t seem to me that one can be everything and in every place. Doesn’t one take care of home first? Might not we over identify with other places and other times, while forgetting that which is closer at hand?

Kalamu: Perhaps in the abstract. But to really care about another, especially others who don’t speak the same language, don’t wear the same skin, to really care about other people, you have to have a profound understanding of yourself as a person. I emphasize, as I say in one of my poems, being a citizen of the world. And you are right, “internationalism” is a loaded term, especially since I don’t care much for nationalism of any sort.

But let me answer both on a more complex and a more realistic level. Our comfort here in America is brought to us by the exploitation and oppression of others all over the planet. Indeed, there are not enough resources in the world to support two Americas. There’s barely enough to support one United States of America. Part of my self understanding came about as a result of seeing the world, interacting with other people in the world, understanding that my existence in New Orleans is directly tied to people in Africa, in China, in Haiti, and so forth.

I wear tennis shoes. I eat fruit year round. I use a cell phone. I use a computer. I drive an automobile. All of that is directly tied to a global economy that exploits the labor and resources of oppressed people. Sweet Honey In The Rock has this song, “Are My Hands Clean.” The song follows the trail of how a blouse that a woman buys is actually made, from cotton plant to retail store. And the song asks, we go into the store and buy this blouse, are our hands clean? By simply making a purchase, are we complicit in the exploitation that is woven into the warp and woof of the blouse’s fabric?

Rudy: You moderate e-drum, a listserv of over 1500 subscribers worldwide that focuses on the interests of Black writers and diverse supporters of our literature. Do you manage it alone? Are you satisfied with its progress?

Kalamu: I do e-drum alone. Spend approximately three hours a day working on e-drum. Yes, I think e-drum is doing important work. E-drum is an example of offering an alternative. E-drum is part of my neo-griot duty to facilitate the development of our culture putting the politics of community empowerment to the fore and offering an alternative to a capitalist orientation. This non-capitalist orientation is far from complete.

On the one hand, e-drum is free to anyone who wants to join. But on the other hand, I can not totally escape the clutches of capitalism. In order to offer the service free, I use a server that adds ads to the content. One alternative is to go with a private service, pay a yearly fee and not have ads attached. Another alternative is to build my own server. My long range plan is to move to a private service and ultimately be in a position to maintain my own server. However, right now, it is more efficient for me to do it the way I am as my financial resources are limited and my time even more limited.

Rudy: You are a professional editor/writer (playwright, poet, and critic), musician, organizer, filmmaker, producer, arts administrator, and radio host. You do extensive traveling and presentations in high schools, universities at home and abroad. How do you manage to have the time and energy for such a schedule of activities? What motivates you, drives you to give so much of your energy and time?

Kalamu: I manage because this is all that I do and because I have the firm support of my wife, my immediate family, and a far flung net of extended family, friends and colleagues. The approval and support of that community is a tremendous validation that enables me emotionally to continue regardless of the hardships and obstacles. I get emails from people worldwide letting me know how much e-drum means to them.

Two weeks ago, I walked into a small restaurant and bar in inner city New Orleans. I was there to buy a catfish plate. While waiting for my order, the brother sitting at the bar next to me called my name. We struck up a conversation. He remembers me from the seventies. He is a welder. He studies African cultures. Sema Swahili (speaks Swahili) to me. Drops a Hausa phrase on me. If you saw him, the last thing you would think is intellectual. His speech is not proper nor laced with big words, but he is an organic, working-class intellectual. He tells the waitress that I am a great writer, and encourages me to keep writing.

Affirmation like that is a major fuel for me, much more so than a positive review from a literary critic, because although I, like everybody, like to get positive reviews, there can be no greater positive review than a Black person walking up to you on the street or in a bar, or a church, or wherever, and telling you that your work is meaningful to them, howsoever they might give you praise. Because of my orientation, that brother in the bar means a lot to me. This work that I do is my life, my religion. Just like many of the jazz musicians I admire would say that jazz is their religion. Well writing (in the broad neo-griot concept of writing with text, sound and light) is my religion. And I am a devout disciple.

The book depicts Ghana as a new African nation of peoples poised for industrial ascension. In his illustration of this theme, Strand produced portraits of students, vibrant marketplaces and technical machinery.

Though he believed in the honesty and objectivity of the camera as an artistic tool, Strand was also well aware of the photographer’s control over their images. Thus, images of technological advancement in the book, are sometimes paired with those depicting traditional cultures and natural environments. While all the images represent the visual “truth” of what Strand’s camera documented, the manner of their juxtaposition implies Strand’s idea of “modernity” comes from a diet of increasing industrial growth and Westernization.

However, it must be said that Strand, throughout his career, took great pains to ensure his portraits of people captured their humanity and their dignity. Unlike some of his Western contemporaries taking patronizing anthropological photographs throughout the continent, Strand’s images identify his subjects by name and often mention their communities as well. The portrait of Anna Attinga Frafra for example, depicts a quiet moment, in which Ms. Frafra rests three books comfortably on her head. An image of such grace could only be taken with the trust of the model.

In the few months Strand spent in Ghana he could not possibly have captured his surroundings with the ease and nuance of Ghanaian photographic great, James Barnor or the newer generation of incredibly talented Ghanaian imagemakers such as TJ Letsela, Nana Kofi Acquah, Ofoe Amegavie and Nyani Quarmyne, yet Strand’s photographs endure nonetheless as windows through the Western lens into the optimism and dignity of post-colonial Ghana.

In Strand’s words again, this time from a 1973 interview:

“The People I photograph are very honorable members of this family of man and my concept of a portrait is the image of somebody looking at is as someone they come to know as fellow human beings with all the attributes and potentialities one can expect from all over the world.”

Asenah Wara, Leader of the Women’s Party, Wa

“Never Despair” Accra Bus Terminal, Ghana

>via: http://africasacountry.com/2014/11/paul-strands-1960s-portrait-of-ghana/

The importing of human beings into the US from Africa to be sold as slaves was outlawed in 1808, after which the slave markets of the southern states traded in black people born in America. The rules of New World slavery decreed that a person’s status was derived from that of the mother, not the father. A slave owner’s children by an enslaved woman were, firstly, assets. Neither Frederick Douglass nor Booker T. Washington considered himself mixed-race, because of the one-drop rule that determined how much black blood made a person black. They loathed the thought of their slave-owning white fathers. Douglass never saw his mother’s face in the daylight, because she was always going to or coming back from the fields in the dark.

What outraged white southerners about Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not only that Harriet Beecher Stowe asserted that black people were better Christians than white people; she was also frank about the immorality of the white man’s relations with the black women in his power. But Stowe had as much trouble as Lincoln in imagining the social destiny of mixed-race people who were pink enough in fact to pass for white (a problem central to Mat Johnson’s brilliantly satirical new novel Loving Day).

In his book The Negro in American Fiction (1937), Sterling Brown called James Fenimore Cooper’s Cora Munro in The Last of the Mohicans “the mother of all tragic mulattoes.” The landfill of American literature includes numerous nineteenth- and twentieth-century novels and plays—by white authors—sometimes condemning, but mostly sorrowing for those racial outcasts who don’t fit in with the black masses but won’t ever be accepted by white society either. “Miscegenation” and “mulatto” are terms of denigration, and the beautiful, doomed mulatto—usually a woman—typically dies after she is exposed before the unsuspecting white man who is about to marry her.

William Wells Brown wrote his fugitive slave narrative and went on to publish in London in 1853 the first novel by an African-American, Clotel; or The President’s Daughter. Clotel is the child of Thomas Jefferson by his mulatto housekeeper, a suggestion of the gossip about Sally Hemings in historical black America. In Brown’s first edition, Clotel leaps to her death in the Potomac rather than be taken back into slavery and concubinage. However, her daughter is reunited in France with the blue-eyed black man she had loved when they were both in bondage. In the edition of Brown’s novel published in 1867, Clotel turns down marriage to a white man in order to become a nurse for Union troops.

Brown named the three possible fates for the mulatto in American literature: death, exile, or renunciation. In the novels of Frances E.W. Harper and Pauline Hopkins, late-nineteenth- century black writers, the black heroines with rosebud mouths who could have passed for white are proud to choose service to their race as teachers over marriage to white men. Black writers were reinterpreting stereotypes.

In James Weldon Johnson’s novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912), a black man who has succeeded in passing for white his entire life, a widower and successful businessman with children, writes his confession, because denying his true racial identity has cost him his soul. In Nella Larsen’s bleak comedy of manners, Passing (1929), the decision to pass is understood as an individual solution to a mass problem, racial discrimination; but the black woman looking at the reckless acquaintance whose white husband does not know he is married to a black woman does not give her away. Larsen, herself something of a tragic mulatto, had sophistication, but passing as a subject in popular culture was the stuff of melodrama. “Once a Pancake,” Sterling Brown called his review of Fannie Hurst’s best seller Imitation of Life (1933), which was twice made into a film.

By that time passing seemed obsolete. The carnage of World War I undermined Social Darwinism; fear of racial mongrelization seemed extremist as a theme. After all, not every mixed-race person looked white; not everyone was desperate to be white; and much Harlem Renaissance writing stresses the varieties of blackness, the different skin tones on display in the ghetto streets. If either you or the law said you were black, then blackness was a shared condition, no matter how light-skinned you were.

Nevertheless, in 1935, Langston Hughes was hopeful of Broadway success with his play Mulatto. That old southern problem: What does a white man do with his black son by his beloved mistress now that his son has grown up and refuses to accept his place as a black man? The son kills his father and his mother holds off the lynch mob as her son prepares to kill himself. In novels and plays about passing, effortful attempts are sometimes made to say that these unions had been loving, if socially impossible.

But the unions that produced the unhappy offspring have already taken place, offstage. There is a reason Faulkner’s mulatto characters are silent men. Hughes included stories about passing in his collection The Ways of White Folks (1934), but he also dealt with interracial romance, which was daring. Then the Communist Party brought interracial sex into American literature in a way that the libidinous Jazz Age had not, apart from the writings of Jean Toomer. In 1934, the Party’s Harlem branch sent its white male comrades to dancing classes so that the black women would have guys to dance with at Party socials, because the black men got so busy with the white women comrades.

Richard Wright, Chester Himes, William Gardner Smith, Ralph Ellison, Ann Petry—the immediate postwar generation of black writers, some of whom had served their literary apprenticeships at Party publications—and white novelists such as Lillian Smith and William Styron assaulted the ultimate taboo, writing fictions that concerned interracial intimacy, as a way of challenging the existing social order. To write about interracial love was considered one of the triumphs of American realism; it was seen as telling more of the truth about the black side of things. But for the succeeding waves of black novelists, from James Baldwin and Paule Marshall to Cecil Brown and Andrea Lee, the interracial love affair became a problem of black identity. This happened before black feminist theory in the late 1970s proclaimed the difference between the experiences of black women and white women and therefore helped to usher in the era of identity politics.

Black conservatives in the 1990s presented themselves as brave dissenters from a juggernaut black-militant, ghetto-determined definition of blackness. They complained about the conformism of black unity; they demanded that blackness be privatized, so to speak, because what they really didn’t like was the liberalism of a black voting bloc. But they were exploiting a crisis of black youth in integrated classrooms. Who you were supposed to be as a black person in these classes seemed too restrictive of what many felt they now contained.

The mixed-race children of the civil rights era and the Second Reconstruction of the 1970s have come of age. Stories about multicultural upbringings and dual heritages have been written for a while now, as autobiography and fiction. The target this time around is not the fantasy of Anglo-Saxon purity, but rather assumptions of black identity. The concerns are sometimes the same as those in the literature about being black and middle-class. What constitutes authentic blackness and who is entitled to say? Race is an unasked-for existentialism.

In Loving Day, “racial patriotism” is just one of the torments that Mat Johnson’s mixed-race narrator must confront. After a considerable absence, Warren Duffy has returned from Wales to his hometown, Philadelphia. Duffy’s mother was black. She died when he was a child. His white father, of Irish descent, has recently died, leaving Duffy a historic but derelict house on seven acres in Germantown, since the 1970s a depressed, mostly black neighborhood.

Duffy, who looks white, can sound black when he needs to. “People aren’t social, they’re tribal. Race doesn’t exist, but tribes are fucking real.” He left behind in Wales a failed marriage and a failed comic book shop—he drew comics himself. He must renovate and sell the Germantown property in order to pay off his former wife, but he also needs a home for the teenage daughter he never knew he had. If he can get her through her last year of high school and into college then he might begin to redeem himself in his own eyes.

The girl, Tal, has been passing for white without knowing it, brought up by her Jewish grandfather. Her mother has been dead for years. Duffy hadn’t seen her since they met as high school students. He stopped calling her and never learned she’d gotten pregnant. Tal’s fatally ill grandfather discovers that Duffy is back in Philadelphia. He hands over his granddaughter, who looks less like her maternal cousins the older she gets. “So, I’m a black. That’s just fucking great. A black.”

In Wales, Duffy had “never felt blacker.” “I don’t like feeling white. It makes me feel robbed. Of my heritage. Of my true self. Of my mother.” Tal enrolls in an ultra-hippie school for mixed-race students, the Mélange Center, a collection of trailers squatting in a public park. Duffy, with no prospects as a comic book artist, ends up teaching at the Mélange Center, which he calls “Mulattopia.” He is skeptical about its biracial cultural indoctrination of embracing all of one’s ethnic makeup. “Oreos” are black on the outside and white on the inside, but “Sunflowers” are yellow and light surrounding a black core:

There are mulattoes in America who look white and also socialize as white. White-looking mulattoes whose friends are mostly white, who consume the same music and television and books and films as most whites, whose political views are less than a shade apart from the whites as well. They ain’t here. Those mulattoes whose white appearance matches up with the white world they inhabit, those mulattoes aren’t coming to Mulattopia. The world already fits well enough for them.

Those mulattoes who look definitively African American and are fully at home within the African American community—they aren’t here either. Those mulattoes who look clearly black and hang black and are in full embrace of black culture—nope, they’re not here, nowhere to be found. If they were they would denounce this lot of sellouts. I know I would. I can hear them from the place they have in my consciousness.

Duffy carries a torch for the black woman who turned him down and married a black policeman instead—until he embarks on a passionate affair with his daughter’s dance teacher, a free spirit, a high yellow like himself. When Duffy meets her other boyfriend, he thinks:

He’s probably one of those white guys who think they’re enlightened just because they’ve realized the obvious fact that black women are beautiful. He’s probably one of those white guys who think poking their pink members in black women will somehow cure racism. I don’t trust interracial couples. I don’t even trust the one that made me: I think of who my father was, who my mother was, and have no idea why they first hooked up, let alone fell in love. I don’t know if I’m the by-product of a racialized eroticism or a romantic rebellion of societal norms. I’m fine with mixed-race unions that just happen, are formed when two people randomly connect. But there are other kinds of interracial couplings with suspect motivation, with connections based on fetishizing of black sexuality, or internalized white supremacy.

The other woman pulling Duffy into the unknown is the older Jewish director of the center itself, “the great matriarch of the new people.” The loopy faculty and other mixed-race students become less like a substitute family for his daughter in Duffy’s eyes and much more like a cult that will derail her life. He plots a desperate act to save her during celebrations of what the school proclaims as the national holiday of mixed-race Americans, “Loving Day”:

In 1958, eighteen-year-old Mildred Jeter got knocked up by her boyfriend, Richard Loving, a family friend six years older than she, and they decided the best thing to do next was get married. They drove up from Central Point, Virginia, to Washington, D.C., because Richard was a white guy and Virginia had a law called the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 that said white people and black people couldn’t get married.

Soon after they got back, the police raided their home in the dark of night, hoping to catch them in the act of fucking, because that was illegal too—which is really ironic when you reflect that the God of Virginia is Thomas Jefferson. They were sentenced to a year in prison, but allowed to have that downgraded to probation as long as they agreed to leave the state and never come back. Six years later, sick of not being able to see their family and broke in D.C., they decided to sue the State of Virginia. It took three years for the Supreme Court to rule in their favor, but it did unanimously, and Loving v. Virginia became the case that decriminalized interracial marriage in America.

Warren Duffy is irresistible in his masculine vulnerabilities, a seductive loser. The appeal of Loving Day is largely in his tone, the fluency of his despair, his flair as an analyst of race and of himself. “Half-European. Whiteness—that’s not really something you can be half of. That’s more of an all or nothing privilege, perspective thing.” But the black woman he used to love is someone who has made up her mind about what race is. Any discussion of it would be an attack on her reality. “Apparently not just black and white people are sleeping together,” Duffy says of the new mixed-race combos possible in America today. He tells her that black people get uncomfortable when they don’t get to have the final say on race in America, and she warns that he is lost in some “crazy Oreo shit,” because “quitting blackness” is of no help in a time of crisis, when black boys are being used for target practice by white cops and the prisons are “overflowing with victims of white judgment.”

Mat Johnson was born in Philadelphia in 1970. His first novel, Drop (2000), relates a young black commercial artist’s attempt to escape Philadelphia and make a life in England. Johnson himself is of mixed-race parentage. In his second novel, Hunting in Harlem (2003), he tried his hand at mystery writing, his hero an ex-con. In his third, Incognegro (2008)—a graphic novel that he created with the artist Warren Pleece, and based perhaps on the experiences of the head of the NAACP, Walter White—a black reporter in the 1930s light enough to pass for white investigates lynchings down South.

Johnson wrote a long, lively essay on the brutal suppression of a suspected slave rebellion in eighteenth-century New York, The Great Negro Plot (2007). His previous novel, Pym (2011), is an ambitious response to Edgar Allan Poe’s weird 1838 novel that has black people inhabiting the South Pole, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.

Johnson is able to interrogate black history. In Loving Day, the one-drop rule is being undermined, shown to be anachronistic; nevertheless he makes it clear that all black people ought to abide in the ship, as black anti- colonialist societies in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century opposed to emigration to Africa urged. You could think of Mat Johnson alongside Wesley Brown, Paul Beatty, Colson Whitehead, John Keene, or Percival Everett. To call them black satirists or humorists wouldn’t quite cover it. In their ease with genre and their consciousness that the language they’re after is literary, they descend through the allegory of Ralph Ellison, not the realism of Richard Wright. But they have inherited Wright’s social vision, not Ellison’s. “I know you’re beige, but stay black,” a friend says to Warren Duffy.

Duffy’s father’s house is haunted. At first, Duffy thinks crackheads are trespassing, but soon Johnson makes it clear that Duffy and a few others have seen the ghosts of the black man and the white woman floating in the air, fucking, “the first interracial couple.” In the end, Duffy isn’t afraid of them. He sees what they are, were. “Just lovers. Just people.”

In 1857, Frank J. Webb, a black writer from Philadelphia, published in London The Garies and Their Friends, a novel about the fortunes of two families, one interracial, the other black. A white planter and his mulatto mistress move for the sake of their children from Georgia to Philadelphia, where racism can be just as violent as in the South. The son who passes for white dies of shame, rejected like a tragic mulatto heroine. His sisters who marry black survive.

SUBSCRIBE to Chescaleigh! http://bit.ly/chescaSUBSCRIBE

Follow My Snapchat! Chescaleigh

Check out my web series MTV Decoded | http://bit.ly/MTVDecoded

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

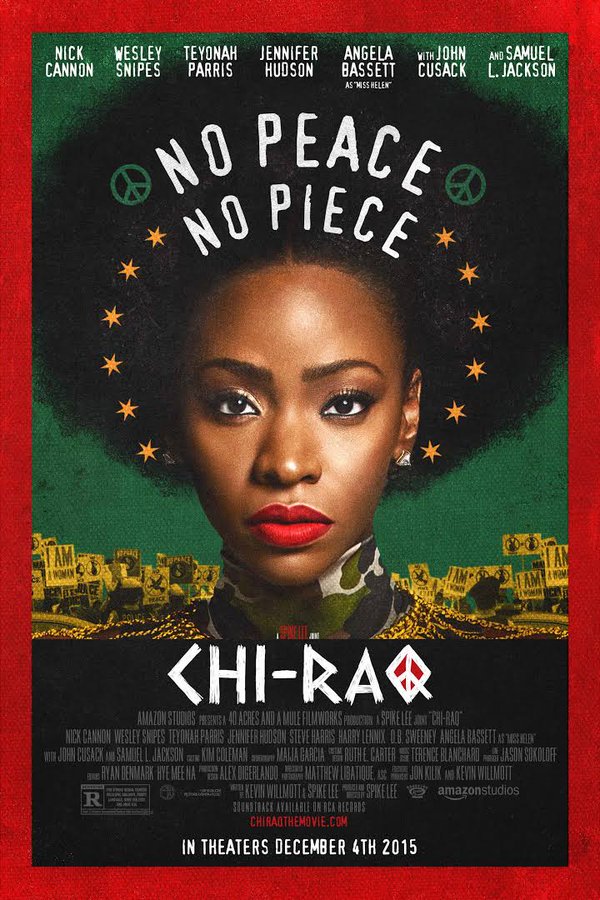

Chiraq and the ‘Sex-Strike’ Myth

http://www.theatlantic.com/notes/2015…

Let’s keep in touch!

Did you know I have a podcast with my husband?? “Last Name Basis” covers our life as an interracial couple and all the stuff we’re interested in, like pop culture, science, weird internet and social justice.

iTunes | http://bit.ly/1yHd3KI

Soundcloud | http://bit.ly/1wU2EnX

Twitter | http://twitter.com/chescaleigh

Facebook | http://facebook.com/chescaleigh

Tumblr | http://blog.franchesca.net

Snapchat | chescaleigh

Instagram | http://instagram.com/chescaleigh

Website | http://franchesca.net

MTV Decoded | http://bit.ly/MTVdecoded

Comedy videos | http://youtube.com/chescaleigh

Hair Videos | http://youtube.com/chescalocs

Vlogs | http://youtube.com/chescavlogs

Nomzamo Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, the beautiful wife of Nelson Mandela during his 27 years in prison, has always polarized the public. Those who love her call her Mama Winnie or Mother of the Nation; they admire her charisma and revolutionary will. Forced into the political spotlight when her husband was arrested, Madikizela-Mandela stoked the flames of anti-apartheid resistance while many ANC members were imprisoned or exiled. But many others fear and vilify her. In 1997, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found Madikizela-Mandela guilty of multiple counts of torture, kidnapping, and murder. Her name was most tarnished by the death of Stompie Seipei, the 14-year-old boy killed by her bodyguards. Madikizela-Mandela’s erasure as a leader corresponded with her husband’s elevation as a saint. While Nelson Mandela’s image was printed on t-shirts and bank notes, his message of peace disseminated in biopics and memoirs, Madikizela-Mandela’s brand of justice was too controversial to market. In her, some people (especially in the mainstream white press) saw a woman whose politics were fueled by hate, and as such she had no place in the mythology of a rainbow South Africa—a nation that had, by all official accounts, reconciled with its past.

During the student protests that have shaken post-apartheid South Africa, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s name was once again on people’s lips. At the University of the Witswatersrand in mid-October, a young black woman was photographed holding a placard that said, “Children of Winnie.” On Twitter, a demonstrator wrote of her leader: “This Hlatswayo girl from #Wits is a new version of mama #WinnieMandela in our generation.” On October 19, students at Stellenbosch University near Cape Town staged an occupation of the Admin B building. Students inside quickly covered up the school crest with a makeshift poster declaring the building’s new title: Winnie Mandela House.

A spring is coming to South Africa, and the protests for free education were only its opening gestures. “Decolonization” is in the works: the struggle to eradicate the economic, cultural, and epistemological logics of colonialism, all of which endured after the end of apartheid. An American transplant to Cape Town the same age as these so-called “born-frees,” I’ve spent the past weeks straddling the line between participant and outsider, listening as my peers narrated and dissected the decolonization process in real-time. On every platform, from the streets to social media, young black South Africans urged society to reinterpret the ideas and symbols whose meanings had ossified over the past decades. Old icons were discarded. Nelson Mandela’s name is sacred no longer—today, to “Mandela-ize” a movement is to attempt to bargain with white power, to sell one’s people short through compromise and false integration. And Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, adored by the youth of Soweto in the 1980s, has gained traction in the activist imagination once more. In today’s black student movement, her historical meaning is being renewed in service of a new political warfare —one that embraces militancy and recognizes the logic of madness, that topples discourses of ‘the past’ to usher in a yet-unimaginable future.

***

“I said I was not going to bask in his shadow and be known as Mandela’s wife, they were going to know me as Zanyiwe Madikizela. I fought for that. I said, I will never even bask in his politics. I am going to form my own identity because I never did bask in his ideas.”

The story of South Africa’s liberation struggle tells the story of the black man. Black women fought for freedom, but they could only move, speak, and act within the patriarchal culture upheld by most resistance groups. This dynamic was crystallized in the Black Consciousness Movement of the 1960s. Mamphela Ramphele, a BCM activist (and later postapartheid liberal politician), noted that few women held leadership positions in resistance movements, with the exception of a handful considered “honorary men.” Most women, Ramphele wrote, participated as an “extension of their role[s] as mothers, wives, and significant others of their male colleagues, rather than in their capacity as individual citizens.”

For Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, the guidelines of female conduct were drawn even more rigidly. Because she was the wife of an imprisoned hero, society expected her to remain faithful. Yet Madikizela-Mandela’s sexual charisma was no secret: the media loved reporting on her multiple love affairs. As a woman, she was expected to wait for the men to bring liberation. But in their absence, Madikizela-Mandela acted as the driving force of the banned ANC—defiant, outspoken, and courageous. Her own party tried to cast her as a domestic trope (a “wife of-”, the “mother of the nation”), but Madikizela-Mandela chose to lead in her own right.

In speaking of Madikizela-Mandela today, students invoke a black female leader who bucked the definitions that her racist, patriarchal society assigned to her. In 2015, black women stood at the front of South Africa’s student uprising. They did so while expressing queer, trans, and non-binary identities—subverting in mind and body the patriarchal logics that govern black power movements and South African society at large. Gone are the days that women acquiesced to fighting for the men’s agenda while subordinating their own desires. At the University of Cape Town, students have been discussing black feminism—a framework that sees racism, capitalist exploitation, and patriarchy as interlocking forces, all of which must be overhauled for decolonisation to be complete. The #FeesMustFall protests carved out spaces in which young South Africans could put these ideologies into practice, modeling new ways of being in the world and, inevitably, of relating to one another.

But it was often within the demonstrations’ internal workings that the microphysics of patriarchy emerged most starkly. Reporting from the four-day occupation at Wits University, journalist Pontsho Pilane observed moments in which demonstrators snubbed their two elected women leaders, gravitating instead towards two male students who had placed themselves at the front. Separately, in an op-ed entitled “You cannot ask women to be vocal in public and silent in private,” Kagure Mugo writes,

Women are some of the loudest and most powerful voices [of the protests]… But what the cameras, interviews and sound bites do not show are the moments when women try and speak within the private political spaces and are hit back with phrases such as ‘this feminism is counter-revolutionary, comrade’.

One trans- woman, Mugo adds, was told by a fellow protestor that discussions around identity were too “expensive” for the movement—that ending racial oppression ought to be the foremost goal.

In mid-November, a young woman from UCT was sexually assaultedby a fellow student at Azania Hall, the source and center of the movement’s intersectional politics. The rape was an expression of patriarchy in its most intimate, most unspeakable form. The event, too, captured the particular double-burden carried by black women leaders in South Africa. As Madikizela-Mandela’s spotlight years demonstrated, the black woman must answer to both the brutality dealt by the public sphere (police tactics, government oppression), as well as the violence that is mirrored or enacted in her private corners (house raids in the middle of the night, silencing and abuse by those she calls her own). “We are the women who have seen in a physical sense the horrors of apartheid,” Madikizela-Mandela told an American journalist in 1990:

We are the women who collected the bodies of our children in 1976. We are the women the government has brutalized year in and year out… The atrocities that have been committed by Pretoria just arise in every mother such bitterness which you cannot put in words.

***

“Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate our country.”

Winnie Mandela gave her most famous speech on April 13, 1986, to a packed hall in Munsieville, a township in Gauteng. “We shall use the same language the Boers are using against us,” she declared, “We have no guns. We have only stones, boxes of matches and petrol.” Traitors would be necklaced, a form of execution in which a gasoline-soaked tire is draped around the victim’s neck and set alight. Even as the country began to transition out of apartheid and other leaders (including her husband) began discussing peace, Madikizela-Mandela stood by her militant position. Negotiating with the enemy, she suspected, could douse the flames of true revolution.

To protest is to speak en masse, and Madikizela-Mandela has re-emerged just as a new revolutionary vernacular is being crafted. In #FeesMustFall, the language of petrol and matches returned with a renewed eloquence. For weeks, students sealed off entrances to their universities with burning tires and forced the schools to close. At the Union Buildings on October 23, protestors in Pretoria set aflame a row of portable toilets. And in mid-November, a month after #FeesMustFall began, students at Stellenbosch, the Tswhane University of Technology, and the University of the Western Cape kept the fires lit, burning debris, buildings, and other campus properties.

More forcefully than any memorandum, the fires expressed this generation’s urgency to tear down the structures in place—to expose, in the process, the violence and absurdity that undergird the visage of South Africa’s “normal and functioning” society. Take, for example, the events that took place on October 19 at the University of Cape Town. That evening, a small crowd of students was occupying an administrative office when the state police arrived to evict them. The officers, clad in riot gear, opened stun grenades and tear gas canisters; they’d been summoned by university management to use whatever means necessary. The violence normalized by the state was mirrored in the reactions of individuals. The first morning that students blockaded entrances to UCT, a white professor, angered by the inconvenience, climbed out of his car and unleashed a stream of expletives on the young, mostly black protestors (including the words “selfish fucking cunts”).

Media outlets interpreted the fires, the stones, and the barricades as hooliganism. They missed the argument. In calling for everything to be decolonized, this generation of protestors is rejecting colonial modes of speaking to power. They’re uprooting Enlightenment ideals of civil and rational discourse; they’re giving the finger to rules of respectability. As the writer and columnist Sisonke Msimang succinctly phrased it, the young ones simply have no fucks left to give. This contempt for state-approved forms of expression has created the space for the return of Madikizela-Mandela: a figure who, throughout her life, voiced her anger loudly, publicly, and without restraint. When asked to confess her crimes at the Truth Commission in 1997, Madikizela-Mandela kept her responses brief, her expression aloof. Against the backdrop of a jubilatory nation, her refusal to participate in forgiveness exercises sealed her reputation as morally bankrupt and mad. But today, armed with the understanding that reconciliation is meaningless without justice, we read her conduct much differently. We see in Madikizela-Mandela a leader who refused to adapt her rage to the formats set forth by those in power.

***

Throughout the protests, whenever the Mandela name arose, I’d ask people what they thought of Winnie Mandela. To one UCT student, the Mandela couple represented the Janus-faced decision that South Africa had to make in 1994. While Nelson Mandela stood for reconciliation, Madikizela-Mandela stood for retribution—the road that should’ve been taken. “Winnie Mandela, now she’s a fighter!” somebody else said, swinging his fist into the air, “She did all the dirty work while her husband was gone.” Another protestor corrected me, saying, “No, her name is Winnie Madikizela. She must get rid of the ‘Mandela’.”

On October 22, the day Madikizela-Mandela was supposed to appear, 15,000 protestors in Johannesburg marched across the Nelson Mandela Bridge to Luthuli House, the headquarters of the African National Congress. But a few hours after the Facebook post (quoted at the outset of this post) began to attract attention, the Mandela Legacy issued a statement: Madikizela-Mandela didn’t have a Facebook profile, and she wasn’t even in town at the time. The profile was a hoax.

Though Madikizela-Mandela never showed up to the protests, she had, in another sense, already arrived—resuming her rightful place among the South African youth. 21 years ago, the country didn’t know what to make of her. But today, it’s precisely the unintelligibility of Winnie Mandela’s image that captures the dizzying contradictions of life as a born-free. She is, all at once, a public figure electrifying but evasive; a consciousness vacillating between psychosis and lucidity; and a soldier eager, after too many years of waiting, to carry the revolution to its conclusion.

+++++++++++

Joy Shan is a Fox Fellow at the University of Cape Town’s African Centre for Cities.

>via: http://africasacountry.com/2015/12/the-return-of-winnie-mandela/

It was her theology—not her hijab—that got her

in trouble with the evangelical college.

By RUTH GRAHAM

I don’t love my Muslim neighbor because s/he is American.

I love my Muslim neighbor because s/he deserves love by virtue of her/his human dignity.

I stand in human solidarity with my Muslim neighbor because we are formed of the same primordial clay, descendants of the same cradle of humankind–a cave in Sterkfontein, South Africa that I had the privilege to descend into to plumb the depths of our common humanity in 2014.

I stand in religious solidarity with Muslims because they, like me, a Christian, are people of the book. And as Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.

It’s that last bit that Wheaton apparently objected to. In a brief statement issued Tuesday, the college said Hawkins had been placed on leave “in response to significant questions regarding the theological implications of statements that [Hawkins] has made about the relationship of Christianity to Islam.” In a longer follow-up the next day, the college clarified that Hawkins’s views, “including that Muslims and Christians worship the same God,” seem to conflict with the school’s Statement of Faith, which all faculty must sign annually. The word “including” in that sentence gently raises the possibility there is more to this story that has not been made public. Hawkins will be on paid leave through the end of the spring semester. (A spokesperson for Wheaton did not reply to a request for comment sent yesterday afternoon.)

There has been plenty of misleading, and even flat-out false, coverage of Hawkins’s suspension; headlines like “A Christian College Placed a Professor on Leave for Wearing a Hijab” are apparently too clickable to resist. But although the statements of Wheaton’s administration have not been particularly warm to Hawkins’s experiment, it has not publicly expressed any objection to it. The school’s expanded statement confirmed her right as a faculty member to wear the head scarf “as a gesture of care and compassion,” and clarified that her suspension “is in no way related to her race, gender or commitment to wear a hijab during Advent.” Hawkins is the first African-American woman to become a tenured professor at Wheaton.

It’s actually progressives, and not theological conservatives, who seem more troubled by the gesture itself. Hawkins, whose research focuses on the black church and public policy, seems aware that she was stepping into a minefield of cultural appropriation. She wrote that she approached the Council on American Islamic Relations for input, asking whether a non-Muslim wearing the hijab was patronizing, offensive, or forbidden. CAIR-Chicago apparently gave her the go-ahead. Slate asked some Muslim women who wear the hijab what they thought of Hawkins’s gesture, and found responses both wary and welcoming. And some progressive Christians found it uncomfortable, pointing out that “trying on” oppression is not the same thing as experiencing it.

Wheaton’s official objection is Hawkins’s conflation of the gods of Christianity and Islam. One level, it is a question of semantics: If there is omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient God, he can at least hear the prayers of everyone on earth, even if they are misdirected. Still, the question is an important one for many believers, because it is related to the question of whether all faiths are equal paths to God.

The phrase “people of the book,” which Hawkins deployed in her statement, is used in the Koran to describe Christians, Jews, and Muslims, who are all said to worship the Abrahamic God. But this is still a matter of significant disagreement among Christians, with many conservative believers resistant to the idea that followers of other religions are pointing their prayers at the God of the Bible. In 2008, Wheaton’s then-president and two other administrators removed their signatures from a letter of solidarity with Muslim leaders, on the grounds that it came too close to suggesting Christians and Muslims worship the same God.

When it comes to academic freedom, religiously affiliated colleges occupy a space of perpetual tension. Those which are serious academic institutions—and Wheaton is one—want to nurture scholarship and free inquiry just like any other college does.

But they also want to cultivate a community oriented around one particular worldview, and everyone who studies and works there understands that. What that looks like in practice can be a source of discord within that community, and at times like this, a source of bafflement and mockery to outsiders. Within the past decade, Wheaton has dismissed a professor who converted to Catholicism, and another for declining to discuss his divorce. The school’s particular strain of evangelicalism is not for everyone—it does not even please all of its students and alumni—but it is also not a secret. (I have a political science degree from Wheaton, but I do not know Hawkins, who arrived there after I graduated.)

Wednesday afternoon, about 100 people gathered on campus to protest Wheaton’s decision to suspend Hawkins. Some female protesters wore hijabs in solidarity; other women had already posted photos of themselves in the comments of Hawkins’s Facebook posts. Other students and alumni started a petition to reinstate “Doc Hawk.” That evening at a press conference in Chicago, Hawkins reaffirmed the original goal of her gesture, and said she will continue to wear the hijab until Christmas. “This Advent, I’m standing up with my Muslim neighbors out of my love for Jesus and the love I believe he had for all of the world,” she told reporters. “And I’m not alone in this.”

>via: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/12/christian-college-suspend-professor/421029/

Deadline: February 1, 2016

For an upcoming issue, Creative Nonfiction is seeking new essays about LEARNING FROM NATURE.

The natural world has long been a source of inspiration. We’re interested in stories about how we learn from nature—whether it’s airlines developing boarding methods based on movement in ant colonies or aviation engineers studying eagles’ wings in order to build more aerodynamic planes; new-age fabric inspired by pine cones or energy-efficient skyscrapers modeled after termite mounds. We’re looking for well-crafted narratives that will illuminate the relationship between humans and the environment, particularly as we face the challenges of climate change.

Essays must be vivid and dramatic; they should combine a strong and compelling narrative with an informative or reflective element and reach beyond a strictly personal experience for some universal or deeper meaning. We’re looking for well-written prose, rich with detail and a distinctive voice; all essays must tell true stories and be factually accurate.

The Biomimicry Center at Arizona State University will award $5,000 for best essay, and Creative Nonfiction editors will award $1,000 for runner-up. All essays will be considered for publication in a special “Learning from Nature” issue of the magazine to be published in fall 2016.

Guidelines: Essays must be previously unpublished and no longer than 4,000 words. Multiple submissions are welcome, as are entries from outside the United States.

A note about fact-checking: Essays accepted for publication in Creative Nonfiction undergo a rigorous fact-checking process. To the extent your essay draws on research and/or reportage (and it should, at least to some degree), CNF editors will ask you to send documentation of your sources and to help with the fact-checking process. We do not require that citations be submitted with essays, but you may find it helpful to keep a file of your essay that includes footnotes and/or a bibliography.

You may submit essays online or by regular mail:

By regular mail

Postmark deadline February 1, 2016.

Please send manuscript, accompanied by cover letter with complete contact information including the title of the essay and word count; and an SASE or email address for response to:

Creative Nonfiction

Attn: LEARNING FROM NATURE

5501 Walnut Street, Suite 202

Pittsburgh, PA 15232

Online

Deadline to upload files: 11:59 pm EST February 1, 2016

.

To submit, please click here. (Note: There is a $3 convenience fee to submit online.)

>via: https://www.creativenonfiction.org/submissions/learning-nature

Thank you for your interest in the Summer Poet in Residence (SPiR) at the University of Mississippi. The residency supports a poet who desires a quiet, beautiful location in which to further his or her work, and it lasts four weeks, from June 15 to July 15

In the summer of 1999, I was awarded a Summer Residency from the University of Arizona Poetry Center and I lived for a month in the charming “poet’s house” on the UA campus. In the years since, I’ve reflected on what a special opportunity that was. Here at the University of Mississippi, we’ve been able to establish a similar residency in the hopes that other writers could receive similar nourishment and support.

—-Beth Ann Fennelly, Director

The residency is designed for poets who have at least one full length book (either published or under contract) and no more than two books. Chapbooks are not full length books. Eligible poets are encouraged to apply.

The SpiR receives housing, a travel reimbursement, and an honorarium of $3,000 thanks to the generosity of The Department of English, The College of Liberal Arts, and the Division of Outreach and Continuing Education. In addition, the SPiR will receive ten broadsides of his or her work, designed by Jan Murray.

The residency is designed to provide ample writing time to the SPiR while also allowing the University of Mississippi’s summer course offerings to be enriched by the presence of a active poet on campus.To this end, the SPiR will be involved in the campus community and the University of Mississippi MFA program by giving a poetry reading and making 1-2 class visits a week. The SpiR will also be invited to serve as judge for the Yalobusha Review’s Yellowwood Poetry Prize. As judge, the SPiR will be given ten finalist poems by the editorial staff and will select the winner and any honorable mentions.

To apply, please send by January 15:

There is no cost to apply. Applications will be judged by Beth Ann Fennelly and Ann Fisher-Wirth. They must be postmarked by January 15th and sent to:

Beth Ann Fennelly, SPiR Director

Department of English

Bondurant Hall C-135

P. O. Box 1848

University, MS 38677-1848

>via: http://mfaenglish.olemiss.edu/spir-summer-poet-in-residence/