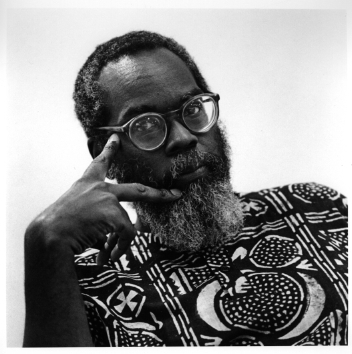

Interview with Award Winning

Neo-Griot Kalamu ya Salaam

[Rudolph Lewis, publisher of Chicken Bones, interviews Kalamu ya Salaam circa 2003. The entire interview plus most of Kalamu’s writings referenced in the interview are available on Chicken Bones > http://www.nathanielturner.com/kalamuinterview.htm]

10

Yusef Komunyakaa & What Is Life?

Rudy: Who are your favorite contemporary poets? Could you tell us a bit about Kysha Brown?

Kalamu: Favorite contemporary poets. Answering that is a recipe for misunderstanding. I have friends. There are also people I would dig if I knew their work. There is so much going on that I dig, If I say four, I’ve got to say ten more, and then that is a hopeless question for me to answer. I could answer about my influences because I have gone back and examined my work and my influences. But there is so much happening today. I can’t possibly do justice to that question. I read a lot. A lot. I hear a lot. Travel a lot. Attend conferences, slams, open mics, lectures, readings, book signings. etc. Everything. I’m always digging the scene.

Kysha Brown. I met her in 1993–if I remember correctly. She is a founding member of NOMMO Literary Society (September 1995). She is my business partner in Runagate Press.

Rudy: There’s the contemporary poet Yusef Komunyakaa, the Pulitzer Prize winner who can be likened to a kind of black Ezra Pound. His poems have become more and more abstruse so that one needs an encyclopedia to understand his allusions. He’s teaching, I believe, at Princeton now, where Cornell took his retreat.

Yusef and I used to be close acquaintances back in the mid-80s. I learned a lot about poetry from him, for which I am thankful. Of course, we had our disagreements. He has a more conservative view of the social world than I. He was a military man; I was a draft resister and part of the black consciousness and labor movements. Have you ever included him in any of your anthologies? Have you reviewed his work? If not, why not? What do you think is the relevance of his work?

Kalamu: He is included in a new anthology I am working on. Yes, I have reviewed his work. I am particularly fond of Dien Cai Dau, his book of poetry about his Viet Nam experiences. As for the relevance of his work, what difference does it make what I think? I think he ought to do what he wants to do—if folk find something useful in what he does, good, if not, let it pass.

My philosophical view is embracement. You don’t try to put somebody out the family just cause you don’t like them. You don’t exclude some people just cause their work is not to your taste. If you don’t dig it, leave it on the table and move on. Yes, there are positions that Yusef takes that I disagree with, but there are positions that Kalamu took in the past that I disagree with today.

This goes back to the dualism and competitiveness question we talked about earlier. I think it’s beautiful that our people can produce both a Yusef and a Kalamu. And I think they are obviously different and that there are many points of divergence between them. Again to go to the music, it’s like we have Errol Garner on one hand and John Lewis on the other. Two pianists: Garner self taught and Lewis formally trained. The strength of jazz is that they could be contemporaries and both be respected for what they do even though their approaches to the music are literally worlds apart and seemingly antagonistic.

Please remember, the acceptance of, indeed, the promotion of diversity is an African trait. In New Orleans we have a song—”Do What You Wanna!” Diversity first. This does not mean that we pretend there are no differences, or that we do not argue for our point of view. Everybody knows that Kalamu got opinions and is not afraid to speak his mind. You don’t have to read much of my work before you see some hard lines drawn, but those are my lines, what I believe. Other people don’t have to agree with me in order for me to dig them or for them to dig me.

If you have a specific position that Yusef takes that you want me to comment on, I will do that. But even when I might strongly disagree with his position, I still embrace him as my brother and salute him as fellow poet and, to be clear, this is not about Yusef per se. Embracement, diversity, those are my philosophical positions in general with everyone. Of course, this is not a blind embracement nor a valueless espousal of diversity. My embracement of my enemies is struggle. My acceptance of diversity does not mean giving way to evil, to that which is anti-life. I will speak out against whatever I consider wrong.

On a national level my first publication was in Negro Digest as a critic. I was reviewing books. Over the years I have have published literally hundreds of reviews of books, records, concerts, events published. I won the first Black World’s first Richard Wright award for literary criticism. My critical work spans over thirty years of publishing. I have come to this position about criticism: I will only review what I like or think is valuable, what I think adds something to our culture. The only exception to that rule is if I think something is dangerous are particularly harmful, I will attack it. Otherwise, it’s live and let live. And I will specifically refrain from dissing something, just because I don’t like it. Within a workshop setting, I will offer my comments on what I perceive as the strengths and weaknesses of a given work, but I will not do so in general.

Without a communal setting the critical comments are often perceived solely as an attack, and often do more harm than any good. Again, we are dealing with African approach. The stronger the communal base, the sharper the criticism can be without doing harm. A strong community enables healthy criticism. But when there is no community, than the criticism usually does not come from a position of trying to help develop whatever is being criticized but rather comes from the position of putting it down. So if you are not in a position to help develop and you don’t perceive a real need to stop or oppose something, than there is no reason to criticize it. From my perspective the purpose of criticism is either to improve that which is being criticized or to defend the community from attack.

Rudy: Do you think that black women writers, especially those who are prose writers, have a greater audience than black male writers? If that is indeed the case, what is the cause of such a phenomenon?

Kalamu: I wrote about the public perception of black women writers in What Is Life? two important essays in that regard “If the Hat Don’t Fit, How Come We Wearing It” and Impotence Need Not Be Permanent. I stand by those statements.

Rudy: I am not familiar with either one of these pieces. Where can they be found? That raises another essential question. So much that is vital is now out of publication? Hasn’t that affected your own influence? Libraries seem to be only interested in the latest. You can imagine some of the black titled that libraries are weeding from their catalogs. I have a book of James Van DerZee that our local library sold for fifty cents. How do we deal with this problem of the control of information?

Kalamu: It is not a problem of control of information. It’s a problem of self-determination. As long as we are content to let others define our culture, our lives, well. As for where those pieces are found, it just so happens they are in one of my few books still in print, the collection of essays published by Third World Press, What Is Life?In fact, I think my responses to a lot of the questions you raise are spelled out in some detail in What Is Life? Maybe forty or fifty years after I’m gone, that book will stand as a statement on the tail end of the 20th century.

11

Cultural & Political Work

Rudy: What do you think is the dominant black cultural ethos today. You, I understand, are more drawn toward a “community ethos.” Is this related to the neo-griot movement?

Kalamu: Commercialization and apolitical creolization are the dominant cultural ethos today. Neo-griot is, hopefully, an alternative.

Rudy: Could you further explain what you mean by the expression “apolitical creolization”?

Kalamu: Creole refers to a mixture. Our integration into the American society is a process of creolization. If we are apolitical about it, then we accept the status quo definitions of economics, politics and ethics. If we were to politicize the process of creolization, we would at the very least argue for and fight for specific modes of social organization, of economic systems, of political systems. But, at this point, all we argue for is a bigger piece of the pie. That is what I mean by apolitical creolization.

Rudy: You have championed the recognition and maintenance of a separate and vibrant black identity. And through the various groups you have founded and motivated, you have increased international awareness of oppression. Is all of this activity related or connected to other domestic movements that are struggling for social justice in the USA?

Kalamu: I’m not sure that I understand this question. but I do emphasize internationalism, more so than domestic identification.

Rudy: I am not sure what you mean by “internationalism.” Marxists and communists used to speak of internationalism. I know that you are neither. It doesn’t seem to me that one can be everything and in every place. Doesn’t one take care of home first? Might not we over identify with other places and other times, while forgetting that which is closer at hand?

Kalamu: Perhaps in the abstract. But to really care about another, especially others who don’t speak the same language, don’t wear the same skin, to really care about other people, you have to have a profound understanding of yourself as a person. I emphasize, as I say in one of my poems, being a citizen of the world. And you are right, “internationalism” is a loaded term, especially since I don’t care much for nationalism of any sort.

But let me answer both on a more complex and a more realistic level. Our comfort here in America is brought to us by the exploitation and oppression of others all over the planet. Indeed, there are not enough resources in the world to support two Americas. There’s barely enough to support one United States of America. Part of my self understanding came about as a result of seeing the world, interacting with other people in the world, understanding that my existence in New Orleans is directly tied to people in Africa, in China, in Haiti, and so forth.

I wear tennis shoes. I eat fruit year round. I use a cell phone. I use a computer. I drive an automobile. All of that is directly tied to a global economy that exploits the labor and resources of oppressed people. Sweet Honey In The Rock has this song, “Are My Hands Clean.” The song follows the trail of how a blouse that a woman buys is actually made, from cotton plant to retail store. And the song asks, we go into the store and buy this blouse, are our hands clean? By simply making a purchase, are we complicit in the exploitation that is woven into the warp and woof of the blouse’s fabric?

Rudy: You moderate e-drum, a listserv of over 1500 subscribers worldwide that focuses on the interests of Black writers and diverse supporters of our literature. Do you manage it alone? Are you satisfied with its progress?

Kalamu: I do e-drum alone. Spend approximately three hours a day working on e-drum. Yes, I think e-drum is doing important work. E-drum is an example of offering an alternative. E-drum is part of my neo-griot duty to facilitate the development of our culture putting the politics of community empowerment to the fore and offering an alternative to a capitalist orientation. This non-capitalist orientation is far from complete.

On the one hand, e-drum is free to anyone who wants to join. But on the other hand, I can not totally escape the clutches of capitalism. In order to offer the service free, I use a server that adds ads to the content. One alternative is to go with a private service, pay a yearly fee and not have ads attached. Another alternative is to build my own server. My long range plan is to move to a private service and ultimately be in a position to maintain my own server. However, right now, it is more efficient for me to do it the way I am as my financial resources are limited and my time even more limited.

Rudy: You are a professional editor/writer (playwright, poet, and critic), musician, organizer, filmmaker, producer, arts administrator, and radio host. You do extensive traveling and presentations in high schools, universities at home and abroad. How do you manage to have the time and energy for such a schedule of activities? What motivates you, drives you to give so much of your energy and time?

Kalamu: I manage because this is all that I do and because I have the firm support of my wife, my immediate family, and a far flung net of extended family, friends and colleagues. The approval and support of that community is a tremendous validation that enables me emotionally to continue regardless of the hardships and obstacles. I get emails from people worldwide letting me know how much e-drum means to them.

Two weeks ago, I walked into a small restaurant and bar in inner city New Orleans. I was there to buy a catfish plate. While waiting for my order, the brother sitting at the bar next to me called my name. We struck up a conversation. He remembers me from the seventies. He is a welder. He studies African cultures. Sema Swahili (speaks Swahili) to me. Drops a Hausa phrase on me. If you saw him, the last thing you would think is intellectual. His speech is not proper nor laced with big words, but he is an organic, working-class intellectual. He tells the waitress that I am a great writer, and encourages me to keep writing.

Affirmation like that is a major fuel for me, much more so than a positive review from a literary critic, because although I, like everybody, like to get positive reviews, there can be no greater positive review than a Black person walking up to you on the street or in a bar, or a church, or wherever, and telling you that your work is meaningful to them, howsoever they might give you praise. Because of my orientation, that brother in the bar means a lot to me. This work that I do is my life, my religion. Just like many of the jazz musicians I admire would say that jazz is their religion. Well writing (in the broad neo-griot concept of writing with text, sound and light) is my religion. And I am a devout disciple.