JULY 29, 2015

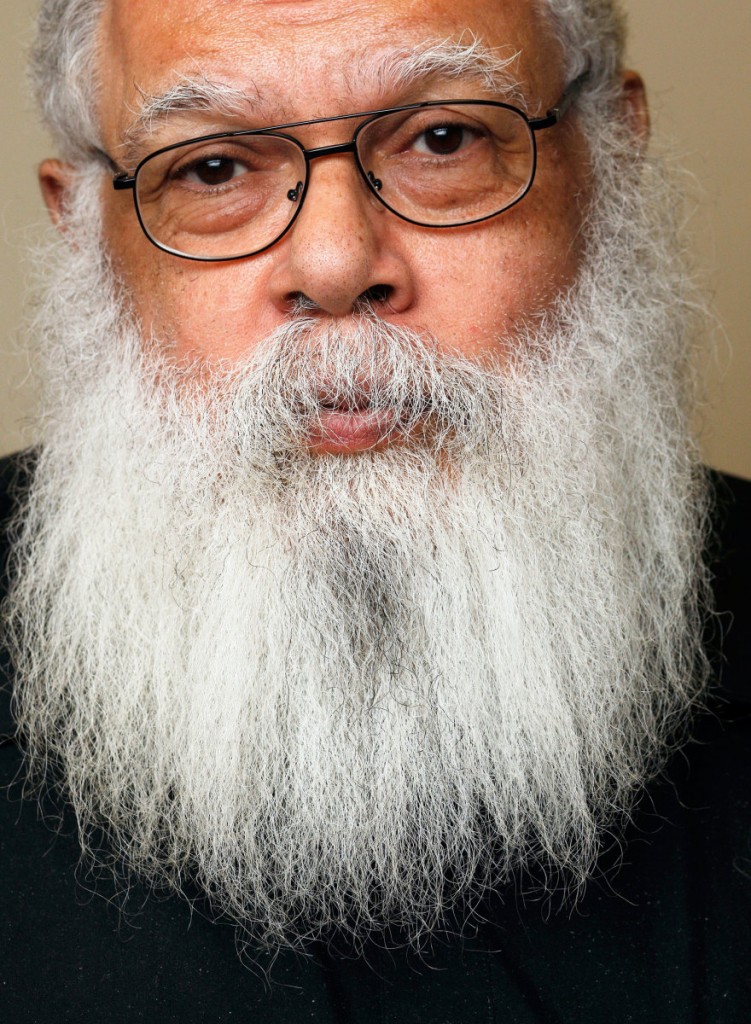

Samuel Delany and

the Past and Future of

Science Fiction

BY PETER BEBERGAL

From the beginning, Delany, in his fiction, has pushed across the traditional boundaries of science fiction, embraced the other, and questioned received ideas about sex and intimacy.

CREDIT PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL S. WRITZ / PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER / MCT / LANDOV

In 1968, Samuel Delany attended the third annual Nebula Awards, presented by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). At the ceremony that night, “an eminent member of the SFWA,” as Delany later put it, gave a speech about changes in science fiction, a supposed shift away from old-fashioned storytelling to “pretentious literary nonsense,” or something along those lines. At the previous Nebula Awards, the year before, Delany had won best novel for “Babel-17,” in which an invented language has the power to destroy (his book shared the award with Daniel Keyes’s “Flowers for Algernon”), and earlier on that evening in 1968, Delany had again won best novel, for “The Einstein Intersection,” which tells of an abandoned Earth colonized by aliens, who elevate the popular culture of their new planet into divine myths. Sitting at his table, listening to the speech, Delany realized that he was one of its principal targets. Minutes later, he won another award, this time in the short-story category, for “Aye, and Gomorrah . . . ,” a tale of neutered space explorers who are fetishized back on Earth. As he made his way back to his seat after accepting the award, Isaac Asimov took Delany by the arm, pulled him close, and, as Delany (who goes by the nickname Chip) recalled in his essay “Racism and Science Fiction,” said: “You know, Chip, we only voted you those awards because you’re Negro . . . !”

It was meant to be a joke, Delany immediately recognized; Asimov was trying, Delany later wrote, “to cut through the evening’s many tensions” with “a self-evidently tasteless absurdity.” The award wasn’t meant to decide what science fiction should be, conventional or experimental, pulpy or avant garde. After all, where else but science fiction should experiments take place? It must be—wink, wink—that Delany’s being black is the reason he won.

On the phone recently, I suggested to Delany that Asimov’s poor attempt at humor—which, whatever its intent, also served as a reminder, as Delany notes in “Racism and Science Fiction,” that his racial identity would forever be in the minds of his white peers, no matter the occasion—foreshadowed a more recent controversy, centered on a different set of sci-fi awards. In January, 2013, the novelist Larry Correia explained on his Web site how fans, by joining the World Science Fiction Society, could help nominate him for a Hugo Award, something that would, he wrote, “make literati snob’s [sic] heads explode.” Correia contrasted the “unabashed pulp action” of his books with “heavy handed message fic about the dangers of fracking and global warming and dying polar bears.” In a follow-up post, citing an old SPCA commercial about animal abuse, he used the tag “Sad Puppies”; what he later called “the Sad Puppies Hugo stacking campaign” has grown to become a real force in deciding who gets nominated for the Hugo Awards. The ensuing controversy has been described, by Jeet Heer in the New Republic, as “a cultural war over diversity,” since the Sad Puppies, in their pushback against perceived liberals and experimental writers, seem to favor the work of white men.

Delany said he was dismayed by all this, but not surprised. “The context changes,” he told me, “but the rhetoric remains the same.”

Delany came of age at a time when the genre was indeed characterized by gee-whiz futurism, machismo adventuring, and white, heterosexual heroes. From the beginning, Delany, in his fiction, pushed across those boundaries, embraced the other, and questioned received ideas about sex and intimacy. And, within a few years of publishing his first stories, he won some of the field’s biggest awards. Delany’s career now spans more than half a century, and comprises dozens of novels and short stories, many of which have challenged every notion of what science fiction could or should be. Even now, when graphic sex and challenging themes are hardly unusual, Delany’s rapturous sexuality and his explorations of race within the trappings of science fiction have the power to startle.

Delany was born in 1942, in Harlem. His mother was a library clerk and his father owned a funeral home. He started writing in his teens, and he turned to science fiction not because he viewed the genre as particularly open to a young black man from Harlem but because, he said, “I read it. It was in front of me.” He married the poet Marilyn Hacker, in 1961, and soon after she took a job at Ace Books, an important publisher of paperback science fiction and fantasy. Hacker dropped one of Delany’s novels into a slush pile under a pen name. In 1962, Ace published the manuscript as “The Jewels of Aptor.” (That work is being reprinted this month alongside two other early novels, in a collection titled “A, B, C: Three Short Novels.”) Delany became something of a wunderkind in the science-fiction world. “You are accepted,” he says, “by the genre that can accept you.”

Delany’s novels and stories have taken place in outer space and the future and other alien worlds. His plots are speculative: the race to harvest an energy source from the sun, the struggles of a libertarian society on one of Neptune’s moons, the plight of slaves in a pre-industrial world of magic and barbarism. But he does not believe that science fiction is the right genre for his concerns any more or less than another genre would be. “Nothing about the sonnet is perfect for the love poem, either,” he said. “Genre simply provides a way for the reader to look for things that have been done. A form is a useful thing to use. It has history and resonance. It informs you as to the way things have been done in the past.” In the preface to “A, B, C,” Delany writes that, “though the genre can suggest what you might need, it can never do the work for you.”

Some of Delany’s works have become essential to the history of science fiction. His 1968 novel “Nova” describes people being plugged directly into computers, a staple of what would become cyberpunk. “Dhalgren,” published in 1975—and one of the more difficult novels in any genre—describes the exploits of the Kid in a post-apocalyptic urban waste virtually devoid of any access to the outside world. Delany’s most recent book, the 2012 novel “Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders,” traces the lives of two young gay men from 2007 into the future. It features coprophagia, bestiality, and the erotic sharing of snot.

No matter how he upends conventions, though, one rarely gets the sense that Delany is trying to shock his readers. “There is nothing in ‘Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders’ that you can’t find on Google in five minutes,” he told me. Just because such acts are not often talked about in polite company does not mean they don’t exist, he said.

This is a lesson Delany learned in part from living in New York City as a gay man in the nineteen-seventies and eighties. In “Times Square Red, Times Square Blue,” a 1999 book that brings together two autobiographical essays, Delany describes the subculture of the Times Square movie theatres in those decades. His sexual exploits are considerable, but Delany focusses his attention on the lives of his partners, such as the one-legged Arly, who will one day go with Delany to visit Delany’s stroke-afflicted mother. In the movie houses sex was not furtive; it was enjoyed openly and without fear, and yet it could only exist in this way within these marginal limits. And it involved a shared language: the men in these theatres talked about what they were doing, whom they did it with, how it went. They created a way of speaking that was as real as any other, no matter how shadowy or illicit people on the outside imagined it to be.

In the contemporary science-fiction scene, Delany’s race and sexuality do not set him apart as starkly as they once did. I suggested to him that it was particularly disappointing to see the kind of division represented by the Sad Puppies movement within a culture where marginalized people have often found acceptance. Delany countered that the current Hugo debacle has nothing to do with science fiction at all. “It’s socio-economic,” he said. In 1967, as the only black writer among the Nebula nominees, he didn’t represent the same kind of threat. But Delany believes that, as women and people of color start to have “economic heft,” there is a fear that what is “normal” will cease to enjoy the same position of power. “There are a lot of black women writers, and some of them are gay, and they are writing about their own historical moment, and the result is that white male writers find themselves wondering if this is a reverse kind of racism. But when it gets to fifty per cent,” he said, then “we can talk about that.” It has nothing to do with science fiction, he reiterated. “It has to do with the rest of society where science fiction exists.”

++++++++++++

Peter Bebergal is the author of “Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll.”

>via: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/samuel-delany-and-the-past-and-future-of-science-fiction