AUGUST 10, 2015

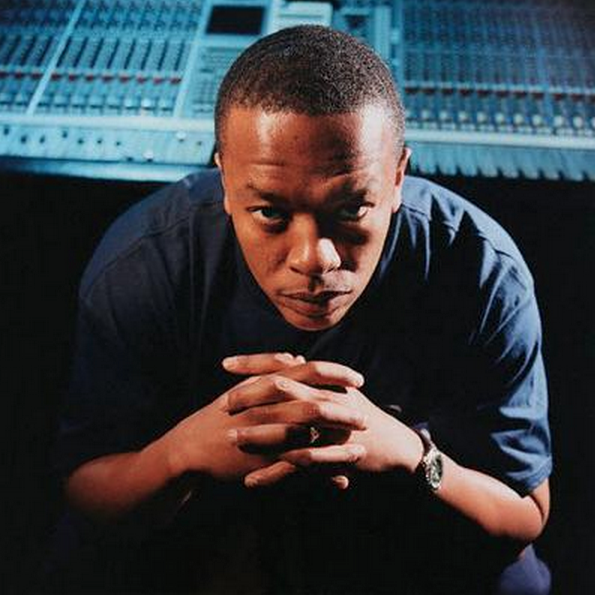

Dr. Dre Does It Again

A new movie and album show why he might be

the greatest hip-hop star ever

By Drew Millard

Let’s do a thought experiment: Imagine Dr. Dre had released his sophomore album—2001, which was originally released in 1999—in 2015. How would the world have reacted?

On the unveiling of the tracklist, the perpetual motion content generation machine that is music media would begin its quick and deadly work. Twitter jokesters would, like a room full of monkeys tasked with typing up Hamlet, collectively figure out the most efficient combination of 2001-related keywords that would yield an anagram that included the word “benghazi.” Outlets would engage in a veritable arms race to be the first to publish articles with headlines like, say “Ten Things You Need to Know About Hittman, the Rapper Featured on Ten Tracks on Dr. Dre’s New Album!” Dr. Dre would have premiered the “Forgot About Dre” video over Snapchat Discover. A sneaky bartender at 1OAK would shoot a surreptitious vine of Taylor Swift dancing awkwardly to “Still D.R.E.” in the Hamptons; it would go viral, the bartender would get fired, and then he’d do an interview with Buzzfeed. The album would leak because Devin the Dude’s vocal engineer had a copy on his iPhone, which he’d end up leaving in a Lyft on his way back from the Supreme store. Some hapless freelancer would be tasked with tracking down the woman from the “Pause 4 Porno” skit in exchange for $100. People would thinkpiece “Housewife” into oblivion—and then the same outlets who wrote all of the Ten Things You Need to Know About Hittman articles would write follow-ups declaring him Problematic, ending his career before he could even offer a half-assed mea culpa via Twitter.

This is all to point out that until last week Dr. Dre had never made a record for the Internet Era. And, considering the lyrical preoccupations of 2001 (not to mention 1992’s The Chronic), that’s probably a good thing. The lyrics of 2001 are immaterial. They’re in service to the record’s thump, its funk. They’re secondary to the rhythms they rest on top of, and the moods those rhythms communicate. But any amount of sonic artistry doesn’t change the fact that this an insanely lewd record: If you don’t believe me, some brave soul made a supercut of every swear word on the thing. It’s 7.7 percent of 2001’s 68-minute runtime.

By the time Dre’s Compton: A Soundtrack dropped last week, the online content engines had reached full throttle. The record—his first in 16 years, rumored to be the good Doctor’s last—has been dissected, analyzed, criticized, evaluated, listsicled and hypotheticalled to hell. Part of this is simple supply and demand: People want to read about what they’re interested in, and the prospect of a new Dr. Dre album is certainly interesting. On the other hand, that rush to create swift and consistent content around an album we knew existed for all of two weeks means that there are a host of voices telling us what to think about Compton and why—which isn’t great. It’s best to let things like this breathe.

Before Dr. Dre’s third album was Compton, of course, it was Detox. First teased by Dre in 2002, the album’s track record of nonexistence that earned it consistent comparisons to Guns N’ Roses Chinese Democracy (and, not to mention, at least one derisive fan t-shirt). At various points, it was set to feature contributions from Nas, Q-Tip, Lil Wayne, Drake, and improbably enough, Denzel Washington. In 2010, Dre claimed to Vibe that he’d put the record on hold because he was making an instrumental concept album about the solar system. Detox, however, is dead. “I didn’t like it,” he said on his Beats1 radio show. “It wasn’t good.” (Though Dre called Compton his “grand finale” on his Beats show, we should all hold out hope for the album about the planets.)

As Detox, Dre’s third album seemed to aim for the scope and impact of Apocalypse Now. Compton, though, doesn’t purport to be a blockbuster. The big-names and high expectations attached to Detox have been abandoned. Compton features names from hip-hop’s past—Ice Cube, Cold 187um, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, and Game all have verses—as well as its future, with the rest of the features given to relative unknowns like Jon Connor, King Mez, and Anderson Paak. Where The Chronic served to showcase a then-ascendant Snoop Dogg and 2001 doubled as a vehicle for Dre’s new high-profile protégé Eminem, Compton works best when it’s showing the novelistic sensibilities of Kendrick Lamar, the latest Dre acolyte to reach superstardom1. The evolution from Cube to Snoop to Em to Game to Kendrick to these new names we’re not familiar with yet: It’s an unsubtle reminder to listeners that hip-hop’s past, present, and future runs through Dr. Dre.

In a way, now is the only logical time for Dr. Dre to put a new album out. Compton: A Soundtrack comes out one week before the theatrical release of the Dre and Ice Cube-produced N.W.A. biopic Straight Outta Compton(titled after N.W.A.’s debut album), which has renewed interest in the legacy of Dr. Dre the musician, as opposed to Dr. Dre the Apple-affiliated headphone pitchman. The film is legitimately great: It’s funny and heartfelt when dissecting the early relationship between members Dre, Ice Cube, Eazy-E, MC Ren, and DJ Yella; it’s heavy and intense when it needs to be that, too. The movie skirts all of the tropes that plague musician biopics—nobody was rescued from a debilitating drug addiction by the love of a good woman, the deaths of real people weren’t crassly foreshadowed, and the movie did a good job of balancing the desires of detail-oriented hardcore fans for easter eggs with the basic needs of people going into the movie having no idea who the hell N.W.A. was or why they were important.

Straight Outta Compton is especially notable because it’s one of the few—perhaps one of the only—mainstream movies that espouse explicitly anti-police sentiments. As the film has it, N.W.A. totally justified in writing “Fuck tha Police,” their infamous track that mixes cop-killing revenge fantasy with social commentary: According to the documentary, the cops were so shitty that the group let them off easy. For perspective, the cops are shown as more sinister than Suge Knight, the film’s villain, whose beguiling charm lures Dr. Dre out of N.W.A. onto Death Row Records, and whose strong arm tactics keep Dre pinned there. He is cartoonishly evil, to the point that he has a nearly nude man tortured by dogs in the lobby of a recording studio, with zero explanation offered to the viewer.

As it’s been pointed out, Straight Outta Compton does take liberties with Dr. Dre’s infamous assault of the journalist Dee Barnes as retaliation for interviewing Ice Cube—at the time of the beating, Ice Cube was on his way out of the group, but the interview found its way into an N.W.A.-oriented segment of the show Pump It Up!. And by “take liberties with,” I mean “completely omits.” It might seem disingenuous to ask Dr. Dre to insert an incident that could torpedo his public image into a movie that he helped produce, but it’s not like he’s ever denied having done it. He referenced the incident in 2001’s “Light Speed,” and the track earns wax during an Eminem duet on “Guilty Conscience.” On “Guilty Conscience” and “Light Speed,” Dre tried and failed to write the incident off as a folly of his youth. He has never publicly apologized to Barnes. When asked about the omission, director F. Gary Gray dismissed the incident as a “side story.” But it’s not, not really, and Dre leaving the incident out in a movie about his own life doesn’t change anything: It still happened, lots of people know it happened, and, by not including it in Straight Outta Compton, Dre has made it clear he’s not sorry. For a man so obsessed with his own mythology and his status on rap’s Mt. Rushmore, it comes off as cowardly.

By 2001, Dr. Dre’s verses2, when they weren’t about blunts and fucking, were concerned his place in history. “We started all this gangsta shit,” he raps on The Watcher, “and that’s the motherfuckin’ thanks I get?” And then on “Still D.R.E.”: “Haters say Dre fell off / How n—ga? My last album was The Chronic.” On “The Difference,” he claims, “Everybody wanna know how close me and Snoop is / And who I’m still cool with.”

Lots of rappers brag about being the greatest of all time. Dre, though, has history on his side. He’s legitimately changed the course of hip-hop at least three times: First by introducing the country to gangster rap with N.W.A.; then by heralding the G-Funk era with The Chronic; and finally by writing the lewdest pop album of all time, the spacey, hyper-modern 2001. In his most recent coup, Dre’s connections, mentorship, and sheer power of his co-sign helped Kendrick Lamar realize his immense potential. In helping shape Lamar’s 2010 album good kid, m.A.A.d. city, Dre helped usher a gentler, more thoughtful form of hip-hop to the top of the charts. Albums like Lamar’s followup, To Pimp a Butterfly, and J. Cole’s 2014 Forest Hills Drive are a counterweight to the gratuitous violence and overt misogyny that peppered the lyrics of their forebears—Dre included—by contextualizing their behavior in the larger societal constructs. It’s not that Kendrick does a better job of documenting the starkness of urban life than, say, Future, it’s just that Kendrick is overt about his intentions. With Future, the listener has to dig a little deeper to find their meaning.

That’s also the case with Compton; its best tracks are the ones on which Dre looks outside of himself, or at least uses himself as a character to make a larger point. On album closer “My Diary,” Dre offers a CliffsNotes version of his own biography: “And don’t forget that I came from the ghetto.” Or consider “Animals,” in which Dre and the Hellfyre affiliate Anderson Paak contextualize inner-city violence within a greater narrative of black oppression: “Nothing but pussy on my mind and some plans of getting paid,” Dre raps, before flipping the sentiment and zooming out, rapping, “But I’m a product of the system, raised on government aid.” That track is co-produced in part by DJ Premier, the New York-based producer who, for a time, defined his city’s sound in the same way that to many, Dre was West Coast hip-hop. It’s the kind of calculated nostalgia-baiting that, if for not the sheer quality of the material, could easily be written off as Dre being trapped in the past—or worse, the hip-hop equivalent of toothless Oscar bait.

Of course Dr. Dre wants to be analyzed and canonized. One does not cement his legacy in the age of information by featuring songs on their album with titles like “Fuck You” and “Deeez Nuuuts.” They do it by producing stately tracks like the soulful “It’s All On Me,”—which, while fantastic, lacks the danger of vintage N.W.A. material—or, say, “Deep Cover.” Then again, Compton is fluid, whatever you want it to be. It moves freely from progressive agitprop (“Talk About It,” “Darkside/Gone”) to classic gangster rap (“Loose Cannons,” “Issues,” “Just Another Day”) to the aforementioned mythmaking and social commentary.

Dre’s been telling us to “bow down on both knees” since “Still D.R.E.” With Compton: A Soundtrack and the Straight Outta Compton film, he’s telling us why he is the way he is. It’s a shame he’s still leaving some things out. Even so, it’s the fullest self portrait Dre’s painted for us so far, and it’s the closest we’ve ever been to seeing music the way he sees it: from on high, appreciating the world he built.

1

Even when Kendrick’s not officially featured, it doesn’t require great leaps of logic to realize that he’s the guy behind Dre’s newfound penchant for rapid-fire, multisyllabic lyrical fireworks.

2

Let’s pause for a moment and address the protestations that the following tracks were penned by ghostwriters and are therefore somehow not “authentic.” Dr. Dre has, classically, pretty much never written any of his own rhymes. That’s fine. Think of Dre like Jeff Koons. Nobody gives Jeff Koons flack for not personally building those giant metal balloon statue things. He’s the guy who decided they ought to exist, and took the steps to make that happen. Similarly, Dr. Dre decided that those verses ought to exist, and so he farmed the actual writing of them out to somebody else. It’s fine. Really. You’ll live, even if Dre, Drake, or whoever else doesn’t write their own shit.