I was in Minnesota. Northfield to be specific. A small town (in)famous for being the site of the ambush and dissipation of the Jesse James gang. Back then–August of 1964 to March of 1965–I was oblivious to how pivotal, how significant, how long lasting would be this point in my life journey. Moreover, I didn’t see how the far north could possibly be a major point in the history of the Deep South. But, indeed, my short stay at Carleton College shaped me then and continues to have impact on me as I approach my 75th encounter with planet earth as it circles the sun.

Carleton is one of the major small colleges in America. The campus includes Cowling Arboretum (approximately 800 acres ), Goodsell Observatory (with three telescopes, one of which contributed to timekeeping in the midwest), and, back when I attended, three gymnasiums, plus a major reputation for outstanding faculty and alumni. There is where I first saw Kanal by Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda. I became a life-long admirer of Wajda’s artistic, politically charged cinema. Carleton’s progressive lyceum series initiated my awareness of people and cultures outside of the USA–in addition to “foreign movies”, I also heard Norman Thomas, Ravi Shankar, and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers during my brief sojourn.

Northfield is a small, college town–it’s also the home of St. Olaf college. The town is about fifty miles south of Minneapolis/St. Paul. Counter-intuitively, my appreciation and critical understanding of New Orleans, grew out of my short stint up where the headwaters of the Mississippi River are located. If you look at a map of the United States, you can appreciate how Old Man River bisects the geography of this country.

Between the Appalachian ranges and the Rocky Mountains, most major rivers flow into the Mississippi River, which means that if you throw a stick in the flowing waters of a large city in most places, stereotypically that stick will end up floating down to New Orleans. Moreover, in this age of planes and trains, most of us don’t think too much about maritime travel, yet for most of the short (in historic terms) life of this country, export goods moved via river traffic.

Indeed, river boat transportation was the life blood of American industrial development. Don’t believe me, ask Mark Twain. And, of course, New Orleans is not only one of the oldest metropolitan areas in North America, the crescent city is also the gateway to the Gulf of Mexico, which offers access to Central and South America, as well as the Atlantic Ocean.

Which all leads me to my understanding of the second great migration of our people. While New Orleans is at the bottom of the southern portion of the country, our city is unlike most of the south. Fortunately for me, after returning home from Minnesota, immediately followed by a three-year stint in the U.S. Army, I joined the Free Southern Theatre and caravanned all across the south, from Texas to the Carolinas.

We went to places where there were no maps and the directions sometimes were to turn by the big tree (“You can’t miss it. You’ll recognize it when you get there.”) That’s how I learned the south. So, for me, the great migration referred to people and places I visited and often intimately knew.

Today, most Black folk have a distant knowledge of the historic great migration: that mythical, 20th century movement of Black people to the northern states. Indeed, even for those who live in the south, it is not uncommon to have relatives in the north, and vice versa. Moreover, the formerly rural areas of America have become urbanized as a result of technological developments, e.g. cell phones, cable/internet connections, and airplane transportation.

One might call this latest Black population shift a reverse migration. Seems as though Black folk are returning back south.

In a July 13, 1865 newspaper editorial Horace Greeley is quoted as advising: “Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.” Well, it seems as though a significant number of Black folk have responded, “Naw, I believe we are Southward bound. Tally ho, here we go!”

Sociologists and public intellectuals have a plethora of explanations for this second migration, ranging from politics, to climate, to the economy. Regardless of why, what is apparent is that Jah people once again be on the move.

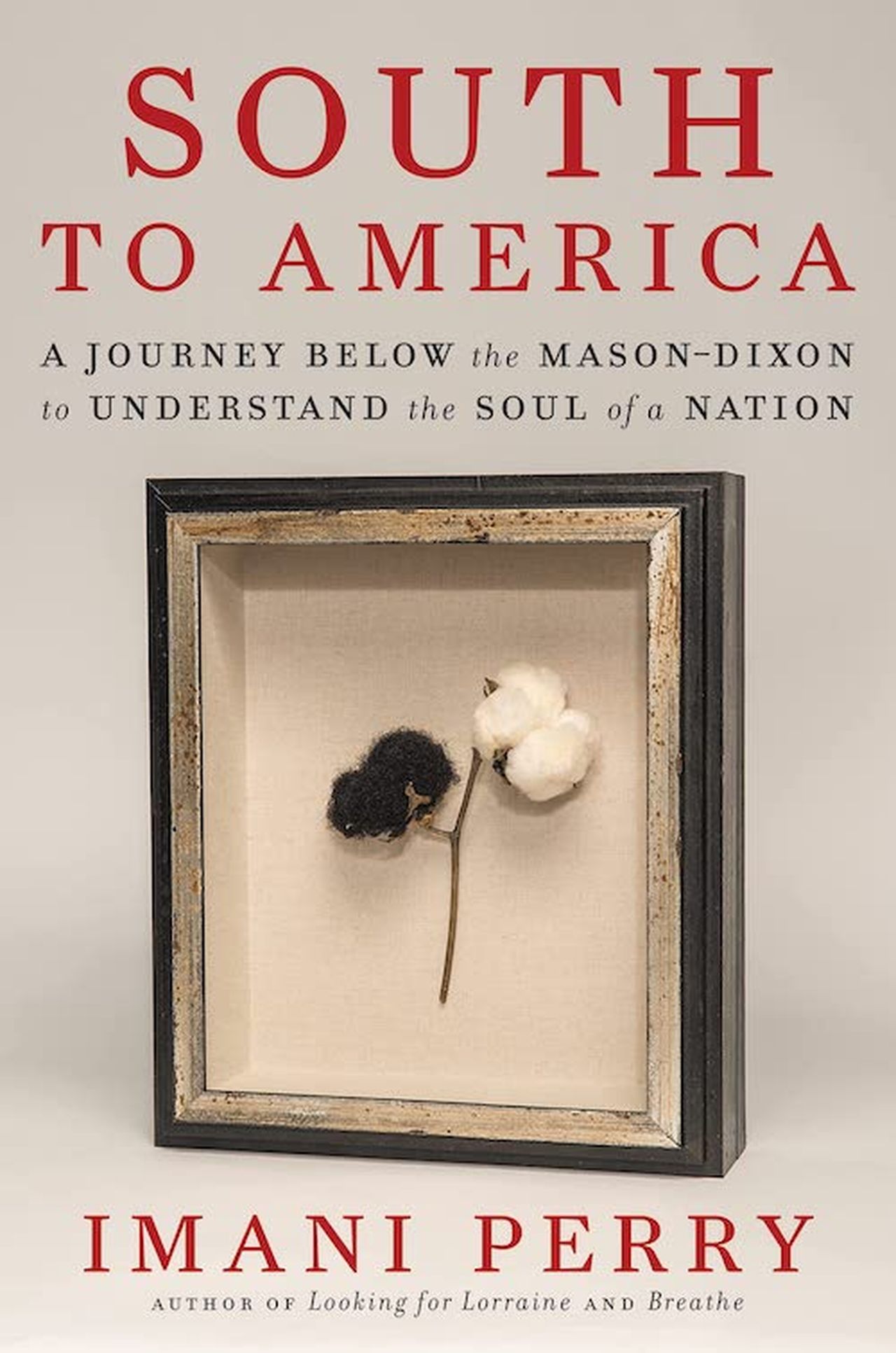

Imani Perry has written a challenging and insightful book exploring the ramifications of this modern exodus. Statisticians and scholars differ about the how-come, where-to, and the sizes of the relocations, but they all agree that something is happening. Even though it is not totally clear what is mainly motivating this movement. Although the genesis and specifics are yet to be definitively determined, the numbers don’t lie, even though there is a great debate about what the numbers actually mean.

Stay tuned…