All Germans are not nazis. It’s not even a case of exceptionalism. You know, like in: ok, they are bad but there are some good Germans. No. What the real deal is: all of humanity contains positives and negatives with one or the other being dominant at different times under various conditions.

My first real inkling that Germany could be hip–not just ok, but actually hip–came when New Orleans visual artist Willie Birch turned me on to Max Beckmann. Decades later, post-Katrina, when I googled the German-born American I found a fascinating visual artist with work featuring Mexico and the mythic American west. His hallmark however was the work he did in the so-called roaring twenties. That was the man whose work I knew thru my deep love of Langston Hughes that began when I was in eighth grade. That was in the fifties.

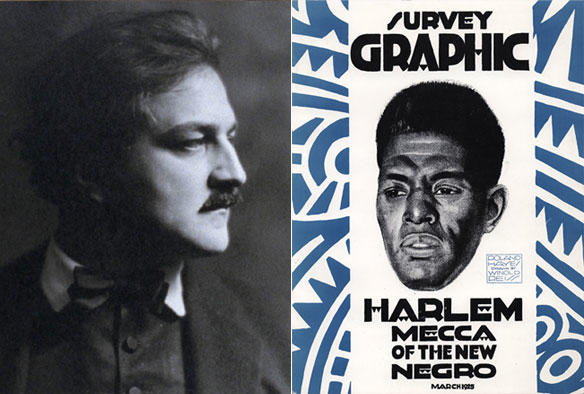

Turns out, Beckmann was aware of Winhold Reiss, whose work I knew from my initial forays into Harlem Renaissance literature. And there it was again: the German connection. I recently read a short article by Tjark Reiss, Winhold’s daughter. She said:

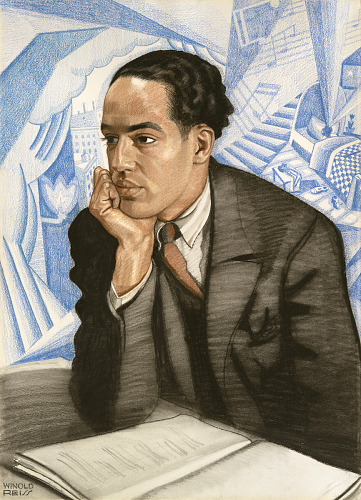

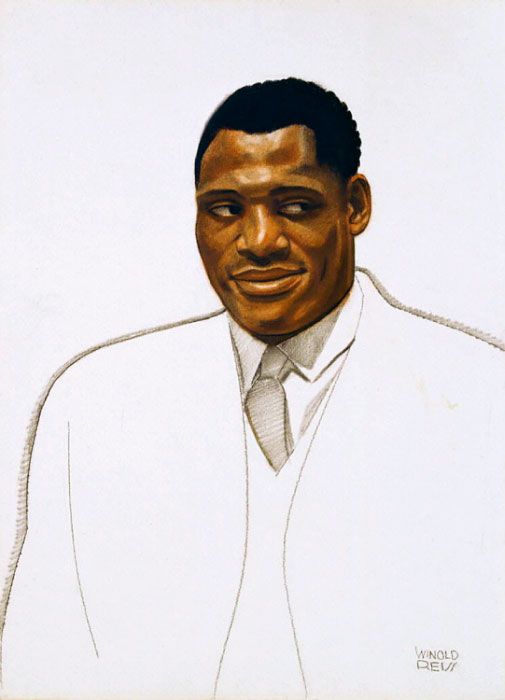

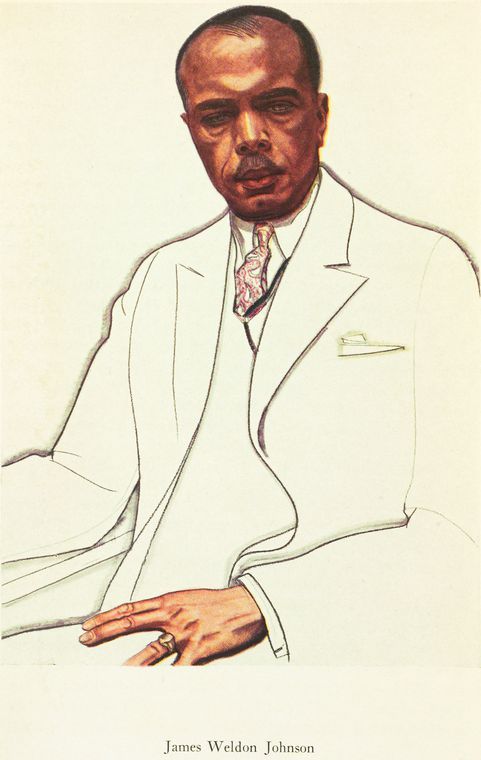

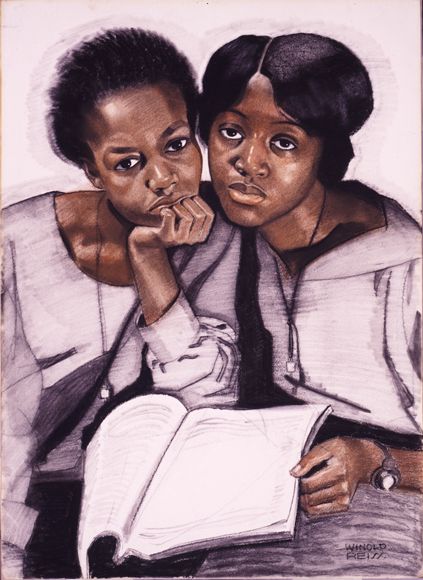

One of his traits that impressed me, particularly as I grew up, was his total lack of racial prejudice. He enjoyed people, and he tried to experience humanity in all its diversity. This love and respect that he carried for the rich variations on the human theme is seen in his portraits. The many racial and national types that he painted express an underlying digni- ty and humanity. He saw not only what race his subjects were but also wanted to know their ethnic backgrounds and to have a sense for how it had affected them.

He was the first artist to devote much atten- tion to painting portraits of Blacks. He would go up to Harlem, and to the Cotton Club, and become completely immersed in Black culture. He loved the music that he heard there. He felt that Blacks — unlike whites — could wear almost any bright color and handle it well because of the strong contrast offered by their skin color.

The deeper I got into Reiss, the more I realized that he was a major contributor to the so-called Harlem Renaissance; I say “so-called” because for me, that period is really the Garvey era. Mainstream America chooses not to honor Marcus Garvey even though he was the founder of the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association, the largest mass movement of African Americans in the history of this country.

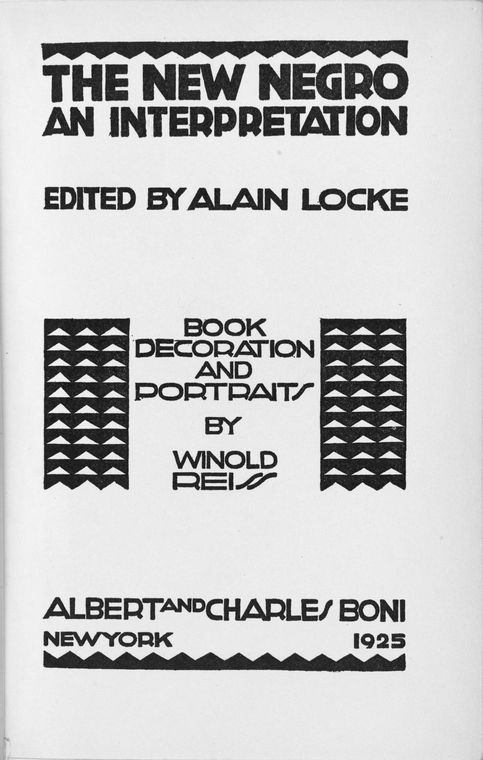

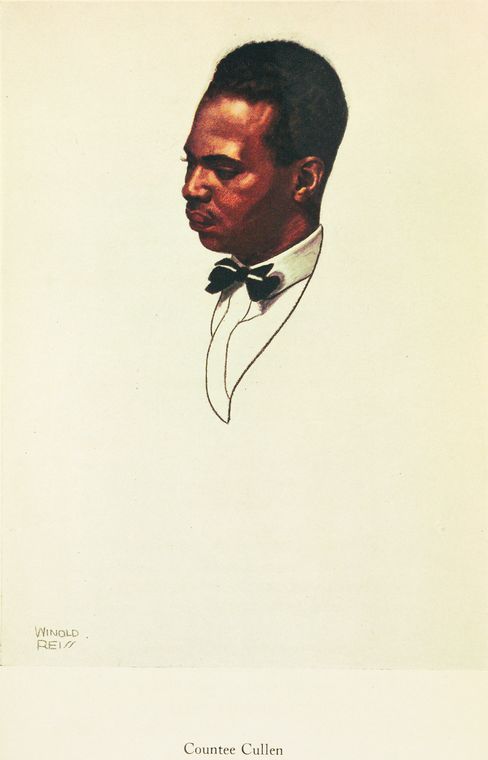

Winhold Reiss’ art work was featured on the cover of the 1925 edition of Survey Graphic. Although not by name but rather by his distinctive images, Reiss is known by subsequent generations of students of the Harlem Renaissance.

My next phase grew out of a life-long adherence to the man who became my literary mentor and highly valued friend: Tom Dent. Tom’s Beckmann influence was not direct. I don’t remember Tom mentioning the artist, nor us ever discussing Beckmann, but I always recall: Tom personally met Langston. My deepest connection was the last time I saw Tom alive. I visited him in the hospital the day before I departed for a trip to Germany. Tom died when I was in Munich.

Subsequently, well after I was teaching creative writing and video production to high school students, I encountered “Our Rhineland”, a short film written and directed by Guggenheim fellow Faren Humes about Afro-German sisters during the Nazi years. Back in the 20th century I wrote about that valued example of cinema, and a number of years later wrote about it again, and now am returning to it for a third time.

My fixation was/is not just with this film, nor with Germany in general, but rather with my philosophical grappling with the questions and conundrums of the human experience, especially we African-heritage persons facing our life in 20th and 21st western-dominated centuries.

For me, the phrase I refer to under a wide variety of circumstances and which I continually mull over is “nothing human is foreign to me’. That keeps me connected to the world, to all of humanity. The aphorism is actually from Terence, an enslaved African writer during Roman times. Terrence wrote “Homo sum: humani nihil a me alien puto.” (I am human. I consider nothing human alien to me.)

That’s my touchstone: in life, and eventually, in death–nothing human is foreign to me.