Semaj Booker made

national headlines

at age 9 for running

away. He hasn’t

stopped running

since.

Semaj Booker stole a car,

snuck on two flights and

became known as

“the most persistent,

most creative and

most publicized”

9-year-old runaway ”

in the history of

the Pacific Northwest.”

That was 10 years ago.

Today he’s trying

to escape from

the environment in

which he grew up.

This is his story.

Prologue

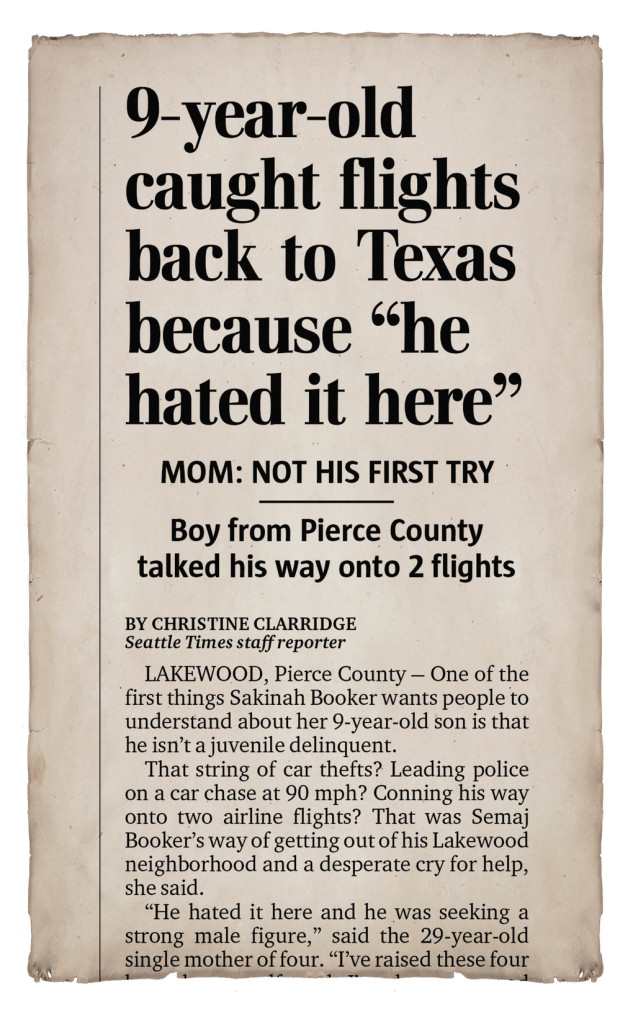

He became the runaway on Jan. 14, 2007, when he crashed the stolen car after a high-speed chase with police. The next morning he snuck out of his mom’s house, boarded a bus for the airport, talked his way into a ticket and flew to San Antonio, with a stop in Phoenix, before any adults caught up to him.

That he stumped multibillion-dollar security efforts left one state representative fuming. That he had the resourcefulness to pull it off made him an object of national curiosity.

Who was this boy from Tacoma?

How did he do it?

And why did he run away?

The Washington Post called him “the most persistent, most creative and most publicized” childhood runaway “in the history of the Pacific Northwest.” Time magazine ran a list of the five most amazing runaway-kid stories. Alongside Benjamin Franklin and Harry Houdini, there he was: Semaj Booker.

Consider him in that moment: baby faced, barely tall enough to race go karts at Six Flags but aware he wanted something more, somewhere better, a new life.

He was 9.

Ten years later, Semaj Booker walked down a street holding what a police officer initially described as “a bundle.” Semaj was animated and waving his arms, as was his girlfriend.

A police officer pulled up. He watched Semaj, now 6 feet 3 with the lanky build of a basketball player, set the bundle down and push his girlfriend into a chain-link fence, according to the police report. Semaj took off his shirt, grabbed the bundle — a car seat containing his two-month-old son — and kept walking.

It was Feb. 11, 2017.

For the last two years, I had chased Semaj’s elusive story, trying to understand his life in the years since he made headlines. But what initially drew me to Semaj — his crazy escapades as a 9-year-old — soon became the least interesting thing about him.

His defense attorney once argued he was a “product of the dysfunction” in his family; more recently, his godmother wrote in a letter of support that Semaj had “many risk factors in his life”; in 2008, a judge ordered a review of his mom’s fitness as a parent, citing confidential records provided by Child Protective Services which indicated physical abuse or neglect and “a pattern of behavior that causes the court significant concern.”

The absence of his dad left Semaj leery of the world at large. “It made me feel like no one is really genuine,” he says. Constantly moving left him always in a new city, a new apartment, a new school, and he pushed away people who supported him for reasons he often couldn’t explain. “That’s all my mom showed me,” he says. “I didn’t want it to be like that.”

It was hard not to care about Semaj after spending time with him, but it was also hard not to fear for him. At every turn, he confronted the challenges of adolescence — relationships, angst about his future, anger — but each challenge was potentially derailing when cast in Semaj’s chaotic life. In just the last two years, he had moved in and then out of his girlfriend’s house, transferred schools, chased his dream to Chicago and mourned the death of two friends. The older he got, the less he talked about his future.

When he had his son in December, he cried, and later I asked him what he most wanted for his child. Our many conversations eventually circled back to the same themes, so I wasn’t surprised when he said stability.

The thing he never knew.

Over time, I found myself in the same position as everyone else in his life: chasing Semaj, all while he chased something just out of reach. But one thing did not change, not in two years. He never stopped running.

When the officer approached on that February day, according to the police report, Semaj’s girlfriend was crying and said he had struck and pushed her. Semaj put a pacifier in his son’s mouth and said he was upset that his girlfriend didn’t change the baby’s diaper enough, that she acted as if she didn’t care. He told officers, “You can’t stop me from leaving.”

He broke free from the officers when they tried to arrest him and sped away in a car, leaving police in pursuit once again.

Consider him in that moment: 19 years old, no diploma, no job, clinging to a basketball dream drifting further from reality.

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 1

The runaway

On Jan. 14, 2007, Semaj stole an idling 1986 Acura belonging to a neighbor. He learned to drive from playing video games.

When he saw the red and blue lights flashing at the interchange between I-5 and Highway 512, he refused to pull over, reaching speeds of 90 mph. He exited the highway, but his engine failed. He wouldn’t leave the car. Police smashed a window. Immediately they recognized him.

Tired and overwhelmed, his mom had instructed police not to bring Semaj home if he found more trouble. But officials at Pierce County’s juvenile detention center wouldn’t take him. The juvenile-court administrator explained at the time that “putting a 9-year-old in our facility with our population is not a good thing.”A few hours after police dropped off Semaj, he snuck out again and stepped on a bus bound for the airport. He approached the Southwest Airlines ticket counter and said he had lost his boarding pass. He gave the last name of an actual passenger and said his mom was already inside the terminal.

They printed him a ticket.

He got through security because children under 18 don’t need ID. A woman let him listen to her music during the flight. He tried boarding another plane once he got to San Antonio, but his luck ran out. Airline employees grew suspicious when he couldn’t explain why he didn’t have a boarding pass or whom he was traveling with.

As for why he ran away, that has always been elusive. Police described him at the time as “incredibly motivated” to return to Texas. His mother called it a cry for help. Semaj maintains that he hated Washington, hated his neighborhood in Tacoma and wanted to see his grandpa in Dallas.

“I wasn’t running away from my mom,” he says. “I was running to a better place.”

Listen: Young Airline Stowaway Faces Charges (NPR)

For years afterward his name kept popping up in the news:

“An 11-year-old Tacoma boy … has been taken from his mother’s home and is in foster care.” — The Seattle Times, Aug. 16, 2008

“Pierce County’s notorious runaway is in trouble again.”— Tacoma News Tribune, Oct. 19, 2010

The Pierce County prosecutor implored the court to declare “enough is enough” in 2008 and hold Semaj accountable for the first time. The judge that day, Frank E. Cuthbertson, laid out the stakes for Semaj, the same ones he has wrestled with ever since.

“It’s time for you to step up and stop all the drama and stop all the nonsense and stop making these bad decisions and be a person who’s going to help your family and is going to help our community,” the judge told him. “For some reason, I still believe you can do it.”

I wasn’t running away from my mom. I was running to a better place” – Semaj Booker

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 2

February 19, 2015

He is 17, a junior at Curtis High School in University Place, and sometimes he Googles his name to watch his highlights. But always he includes “basketball” or else he gets the bad stuff.

He’s athletic in ways most people can only fantasize. He dunks and shoots three-pointers and runs the court in just a few strides. But some people tell him he looks awkward, as though he’s still learning his body.

This is his first year at Curtis, his third high school in Washington, and he also lived in Texas and North Carolina. Curtis is harder than his other schools, especially math, so sometimes he gets in trouble for listening to music during class.

He works as a referee and gets paid $10 an hour. One time, he worked nine hours but his check was for $83. His response to this fact of life: “Come on, man!”

He didn’t start playing organized basketball until middle school, but now it’s everything to him. He wants to dunk on every team in the league. He loves hearing his name in the starting lineup. “It makes me feel important, I guess,” he says. He’ll talk forever about his favorite movies and TV shows, almost all of which are cartoons: “Big Hero 6,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” “Pokémon.” None of his teammates make fun of him for this.

“Well, OK, none of them know,” he says.

He dreams of the places basketball can take him, and all of those places are somewhere else. He received a generic recruiting letter from San Diego State, but while the idea of college basketball excites him it also gives him pause.

“I’m going to take the SATs,” he says, “but I already know I’m not going to do good on it.”

Instead he talks about playing overseas — what he calls his “main goal” because he wants to see the world. “I just can’t wait,” he says. “I don’t have that much time left growing up so might as well think of it now.”

One thing he likes about Curtis: No teacher has ever asked him about being the runaway.

Curtis HS forward Semaj Booker is introduced at the start of a district playoff game with Federal Way. (DEAN RUTZ / The Seattle Times)

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 3

Feb. 26, 2015

The night before the final game of his junior season, he eats with his mom at the Applebee’s near their apartment. Her name is Sakinah Booker. She can’t make it tomorrow night, the game is in Chehalis, and anyway, she feels like an outsider. She’s a single mother, and it seems everyone at Curtis has their mom and dad, their aunts and uncles, but all Semaj has is her.

She does most of the talking. Semaj watches an old Sonics game on TV. There’s a picture on the wall of a team at the state tournament, and the last time Sakinah was here she asked the manager if they could replace the picture with her son’s team if he made it to state.

Their relationship has always been complicated. She admits that Child Protective Services was at her house recently to look at one of her children, which was also the case when Semaj was younger. He regrets the trouble he caused her, but as he has grown up, he has also grown more independent.

“He’s just a teenage boy trying to figure things out, and mommy can’t always be there,” she says. “I don’t get my hugs and my loves like I used to. We don’t do that as much. He has a life now. But, see, that’s what I want for him.”

After Semaj’s story spread, Sakinah and Semaj went on “Dr. Phil,” which earned a reprimand from the judge. But she claims it was not a stunt. It was about getting Semaj counseling, something Sakinah says Dr. Phil’s people had promised to do.

Same for when she appeared on “Inside Edition” and said she was proud because Semaj showed her he could “achieve” anything he wanted. That was survival mode. She says “Inside Edition” agreed to pay for her flight and hotel so she could pick up Semaj in San Antonio.

She had to do what she had to do.

He’s just a teenage boy trying to figure things out, and mommy can’t always be there.” – Sakinah Booker

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 4

March 5, 2015

His Curtis team comes up one game short of state, so Semaj watches from the bleachers. At the concession stand, he shakes hands with a Division I coach but he’s so nervous he barely talks. Later, he says it’s the first D-I coach he has ever met.

In the background at the Tacoma Dome, the announcer calls out players. A pep band plays “Living on a Prayer.” No matter how much he tries to avoid it, no matter how much he lets the game distract him, his past always comes up.

He thinks about it every day. His mom tells him he needs to open up, but he won’t. He went to a therapist but wouldn’t talk.

“I don’t like crying, and it will make me really emotional,” he says, avoiding eye contact.

As reserved as he can be, he can be just as quick-tempered. His moods change abruptly. He tries to hide his feelings, but sometimes his anger spills out in fights. As if a giant gate swings open and all his hidden rage rushes out.

It’s a side of himself he doesn’t like.

On the car ride home, he says he’s going to a school dance the next night. His first. But he is not nervous, he says, shrugging, smiling.

“OK, of course I’m nervous going with a girl,” he admits.

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 5

April 12, 2015

He was in a fight at Curtis, and it was bad, and he might get expelled. He’s not sure, but he knows he’s in trouble. The fight was over something avoidable, some perceived slight he couldn’t let pass.

He had to be pulled off the other student, and only later did he realize what he’d done.

“I just felt sad after because I didn’t mean to hurt him,” he says.

He’d been showing up late to school, missing his first and second classes, and then the fight. It’s why people fear for him. He is 17, but had it happened only a few months later, after he turned 18, he could have faced more severe legal trouble.

For all his rough edges, Semaj can be heartbreakingly endearing. Vulnerability doesn’t embarrass him. After every game at Curtis, he thanked the coach’s wife for baking cookies, so he became her favorite player. Everyone around him believes Semaj wants to be loved, but at times he seems incapable of accepting that love.

Andy Nelson, his AAU coach, is one of the people pulled into his vortex. He lets Semaj stay at his house, drives him to games and washes his clothes. He sees the innocence of a boy inside the body of a grown man.

A couple of summers ago, Nelson and Semaj were driving around Tacoma the day before flying to California for a tournament. Suddenly, Nelson realized he was about to get on a plane with Semaj Booker.

“Do you have your ID?” Nelson asked.

Semaj looked at him curiously. “What do I need that for?”

Nelson explained that in order to get through security at the airport, people had to show identification.

“You, of all people, we’ve gotta get an ID for,” he said.

Semaj laughed. “I think they made those laws because of me.”

Some of the happiest times in Semaj’s life have been at basketball tournaments in California. He went to Disneyland and rode his first big roller coaster. “I was scared, not going to lie,” he says. “I screamed like a girl. The second time we went on it, I was just happy because it was fun and I was around people I liked.”

He had $2 in his duct-tape wallet on another trip before Nelson and a parent chipped in. He ate three funnel cakes in one day and wanted another, he liked them so much. At the arcade, his teammates asked why he was so good at a high-speed driving game.

“Do I even need to answer that?” he dryly answered.

In those moments, Nelson sees Semaj as an “agent for change.” Nelson feels like he will have failed if he doesn’t watch Semaj get his diploma, if he reads something bad about him in the paper.

“I don’t know if I could live with myself if I didn’t invest in him,” he says.

Everyone around Semaj sees his life heading one of two ways, including Semaj. He has the capacity to escape his environment, but he could also be someone … “who just messes up,” he says, finishing the thought. “I look at it the same way.” He is on the verge of becoming a man, but no one knows what kind of man he will become.

His past trails him everywhere, and even if he manages to forget about it, people remind him. Prying adults bring it up, unable to contain their curiosity. Semaj knows what to say, but it’s weird telling an adult.

What he never tells them, what he can barely talk about, is foster care.

He was 11 when he and his siblings had to leave their mom. He and his older brother ended up in a house together, but they were separated after a fight.

Cain and Abel, his mom calls them. Semaj knows his brother blames him for splitting up their family.

“My mom says it’s not my fault,” he says, locking eyes, “but in my heart I know it is.”

Semaj hated foster care so much he ran away. Pedaled his bike until his legs burned and he reached his mom and sister.

“I felt like I was in exile,” he says. “I just wanted to be alone from the world. I just wanted to be in a cocoon. Just a person with some headphones.”

When the police knocked, he tried to hide under the futon. He crawled into bed with his mom and little sister and begged not to go back. His mom told him he had to, that both of them would get in trouble if he didn’t.

She looked at him and said, “You’re better than this.”

I felt like I was in exile. I just wanted to be alone from the world. I just wanted to be in a cocoon.” – Semaj Booker

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 6

July 1, 2015

A lot has happened, he says. He was suspended from Curtis for a week, and soon after, he started talking about how uncomfortable he felt at the school. He moved out of his mom’s apartment following an argument and moved in with his girlfriend.

He goes to Oakland, an alternative high school in Tacoma, and is trying to get a fifth year of eligibility to play basketball.

He no longer has a phone.

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 7

July 20, 2015

Semaj and Andy Nelson are on the road. Nelson says Semaj played his ass off against a future D-I player in Vegas. Semaj thought it was pretty cool when Nelson introduced him to coaches at a small junior college.

“He’s created some opportunities for himself down here,” Nelson says. “Don’t want it to go by the wayside.”

When they get back, Nelson drops Semaj off, and they say an awkward goodbye.

He feels Semaj running away.

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 8

Nov. 5, 2015

He unbuckles his seat belt and slides out of the car when he says, “A lot of my friends are dying.”

Just three days ago, one of Semaj’s friends, an 18-year-old named Elijah Crawford, was shot and killed. Semaj woke up to the news the next day. He left school early and went to see his mom. He couldn’t stop crying.

“I knew him,” he says. “I knew him as a person. I knew who he was and who he grew to be. He grew to be a man — a young man.”

He lost another friend, Lorenzo Bolden, in August when one of Bolden’s friends accidentally fired a gun. The bullet struck Bolden in the head. Semaj has video on his phone of him and Bolden playing basketball.

A family friend has never seen Semaj so inconsolable. He spends more time in the gym and even has a phone again so college coaches can reach him.

“I want to make it,” he says. “That’s why I’ve been in the gym. I want to get out of Tacoma. They tell me I have the power to get out of Tacoma, but it’s on me.”

He stares at the Trail Blazers game on TV. It’s hard for him to talk about this.

The deaths of his peers forced him to come face to face with his own fragility, his own precarious place in the world, and what scares him most is turning into his environment.

“I’m not young anymore,” he says. “Like, the world is kind of a bad place.”

When the beignets topped with whipped cream and ice cream arrive, he lights up. He shovels a spoonful, takes a big bite and holds up the spoon for inspection. “Ooooh, these are nice!” he says.

They remind him of funnel cakes in California.

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 9

Nov. 23, 2015

He is nervous. He goes to Clover Park and his appeal for a fifth year of eligibility is in the afternoon. If he loses, he can’t play basketball.

And without basketball, he once said, he wouldn’t have any motivation.

He is no longer in touch with Tim Kelley, Curtis’ coach, who says Semaj vanished, or Andy Nelson, his AAU coach, who hasn’t heard from him in months. He seems to know everyone in Tacoma but keeps few people close.

“He has all this potential, but then he has that part that will fly at any time,” Nelson says. “What’s happening now is his window is closing on his opportunities, and he’s feeling anxious, he’s feeling nervous. And he’s running to the next, easiest thing to get him by.”

After school, Semaj spends 30 minutes explaining why much of his life has been out of his control. It doesn’t take long for word to reach him: His first game is in a week.

He has all this potential, but then he has that part that will fly at any time.” – Andy Nelson, AAU coach

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 10

May 2016

Clover Park High School basketball player Semaj Booker goes up for a basket before playing in the Clover Park Warrior’s playoff game against the Washington Patriots at Foss High School in Tacoma, WA, Monday, February 15, 2016. (Ellen M. Banner / The Seattle Times)

He had a good senior season at Clover Park. Good enough that the coaches at Tacoma Community College noticed.

“We had intentions of taking Semaj on with us for a while,” says Joe White, the school’s assistant coach. “But as soon as we started showing more interest, Semaj veered away.”

White and his coaches haven’t heard from Semaj in months. The same scenario unfolded with Evergreen State College. Mel Ninnis, Semaj’s coach at Clover Park, fears for him. Semaj didn’t go to Clover Park’s season-ending banquet and stopped going to class.

“We’re all broken,” Ninnis says. “We all have scars and mistakes. But when he really exposes himself to his teammates, it becomes very transparent that he is in grave need. He needs so much to become a complete, whole man who has inner peace. Honestly, he needs a lot.”

On the last day of the month, Semaj sends a message: “My girlfriends pregnant and I leave August first to this prep school.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 11

Jan. 18, 2017

He walks into the mall pushing a stroller. He looks the same — tall, lanky, distant expression — but also a little weary.

“This is Mathayus King Blue-Booker,” Semaj says, pulling the blanket away.

For three months before his son’s birth on Dec. 22, 2016, Semaj had lived in Illinois with his mom. The plan was for him to play at a prep school — to finally get away — but he never went to prep school. He returned to Tacoma and cried during his son’s birth because his girlfriend was scared, and he didn’t like seeing her like that.

He rubs his temples and covers his whole face with his large, thin hands.

“It’s been shitty,” he says, looking at his girlfriend and son. “Besides her and my family, I didn’t really have anything else I really cared about.”

Already, Semaj admits, he has trouble expressing affection and talking to his son, but he knows the pain of not having a father.

“When I look at him, it makes no sense that somebody wouldn’t want to be around him,” he says. “At the end of the day, I love him no matter what, and I can’t do my son like that.”

Semaj Booker at Kobayashi Park in University Place on Monday, June 6, 2016. Booker says he often comes to the park with friends. “I like the sound of the water,” he says. (Lindsey Wasson / The Seattle Times)

They tell me I have the power to get out of Tacoma, but it’s on me.” – Semaj Booker

✦ ✦ ✦

Chapter 12

Feb. 11, 2017

A police officer found Semaj pulled over on the side of the road. But when the officer flipped on his lights, according to the police report, Semaj jumped in the car and drove away again.

The officer rammed Semaj’s car into a ditch, at which point Semaj took off running. Once the officers cornered him, he ran up the hood of a police car, leaving a behind a dent on the roof, and fled into the woods and was arrested.

By then, Semaj had racked up a troubling list of charges: third-degree assault, eluding a police vehicle, fourth-degree assault/domestic violence, resisting arrest and third-degree malicious mischief. When asked why he fled, he said he didn’t like to be touched and had anger issues.

He also apologized.

In a letter of support, his girlfriend called him “thoughtful, mindful, generous, and giving.” She wrote he “loves basketball,” that he could “go pro,” that he “wouldn’t mind doing that for the rest of his life.”

“He’s so close to his dreams!” she wrote. “It would really suck if this mistake jeopardized that in any way. … Semaj’s so bright and has so much potential he just needs firm guidance and a stable role model in his life.”

The life he’d never known.

Epilogue

When I heard about Semaj’s arrest, I was crushed. For his girlfriend, for him, but mostly for his son.

From the beginning, people talked about Semaj’s potential to be an “agent of change,” to “break the cycle” of his life. It was the thing he was running toward and the thing he was running from.

Maybe he can still be that change.

For more than two years, Semaj and I became a part of each other’s lives. We talked about LeBron James and beignets, about anger and restraint, about what inspires him as well as what scares him. He always answered my messages and questions, one of the few people he kept around, but he hasn’t responded to me since February.

His court date is set for July 26.