16 Harsh Realities

of Being Black

and/or Mixed

in Brazil

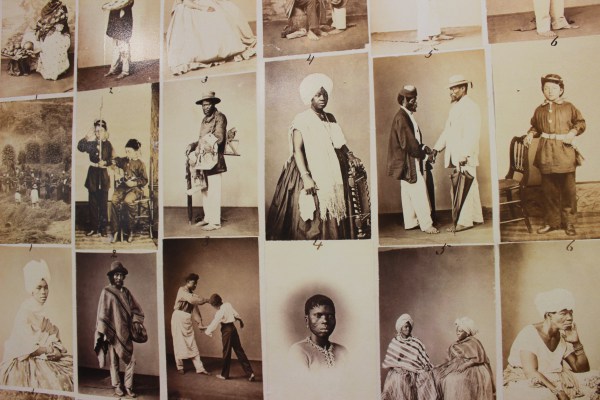

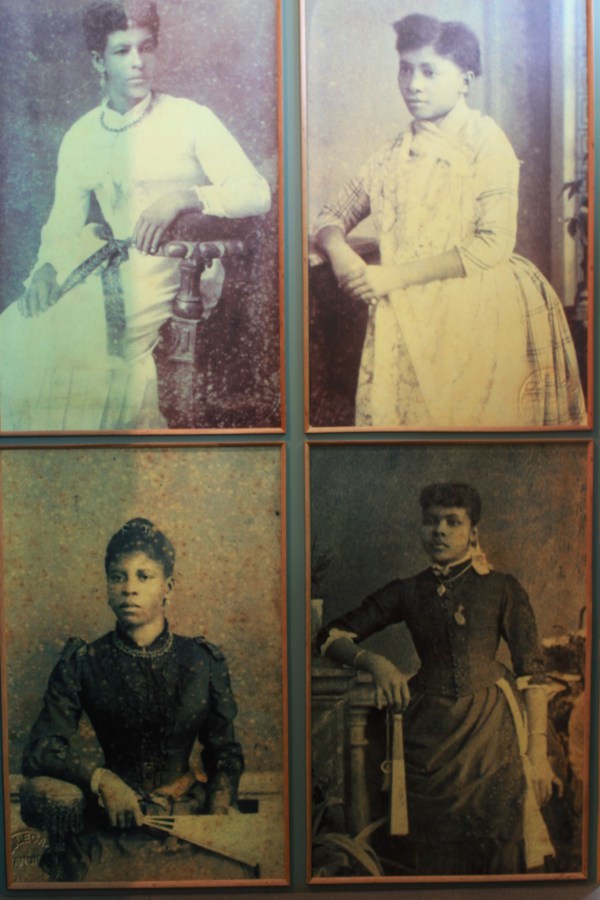

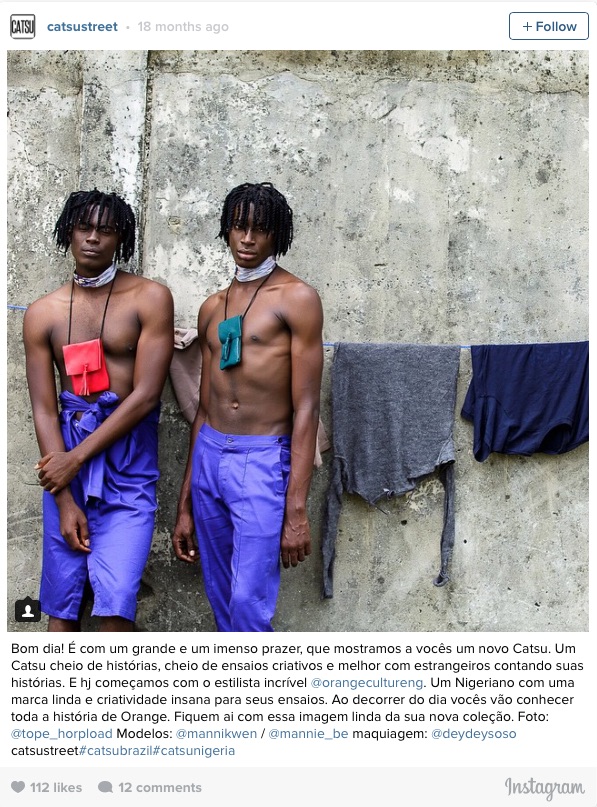

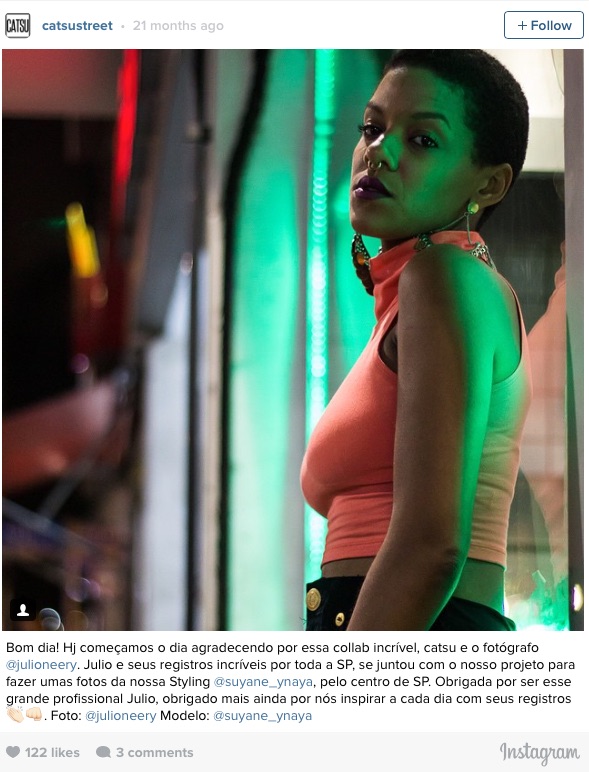

The Instagram photos spread throughout this piece are from the Brazilian art and photography collective CATSU, which documents the beauty and vitality of black and mixed culture in Brazil. Read more about them here.

On July 31 Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail released an expansive, 9,000+ word report on race in Brazil. That the series even exists is amazing because Brazilians strongly deny the existence of race or racism in their country, and perceive themselves as the ultimate mixed culture. And in many ways they are — a full 51% of Brazillians describe themselves as black or mixed race. But beneath the facade of a diverse country are racial inequalities that are, in some instances, worse than what blacks suffer in the United States.

Here are 16 harsh realities of being black and/or mixed in Brazil we learned from The Globe and Mail’s report;

1. Many black Brazilians hope for their children to have white skin so they do not suffer as they do.

The article opens with the story of Daniele de Araújo, a dark-skinned mixed Brazilian woman whose one prayer when she found out she was pregnant was for a white-skinned baby.

She told God she wanted a girl, and she wanted her to be healthy, but one thing mattered above all: “The baby has to be white.”

Ms. de Araújo knows about the quixotic outcomes of genetics: She has a white mother and a black father, sisters who can pass for white, and a brother nearly as dark-skinned as she is – “I’m really black,” she says. Her husband, Jonatas dos Praseres, also has one black and one white parent, but he is light-skinned – when he reported for his compulsory military service, an officer wrote “white” as his race on the forms.

And so, when their baby arrived, the sight of her filled Ms. de Araújo with relief: Tiny Sarah Ashley was as pink as the sheets she was wrapped in. Best of all, as she grew, it became clear that she had straight hair, not cabelo ruim – “bad hair” – as tightly curled black hair is universally known in Brazil…

And there is no point being precious about it. Black is beautiful, but white – white is just easier. Even middle-class life can still be a struggle here. And Sarah Ashley’s parents want her life to be easy.

2. Many dark-skinned Brazilian women are seen as only good for domestic labor, and dark-skinned Brazilian men are seen as only good for service jobs.

It is a cornerstone of national identity that Brazil is racially mixed – more than any country on Earth, Brazilians say. Much less discussed, but equally visible – in every restaurant full of white patrons and black waiters, in every high rise where the black doorman points a black visitor toward the service elevator – is the pervasive racial inequality.

3. During the slave trade, Brazil imported more slaves than any other country

Brazil imported more slaves than any other country. Fully 20 per cent of all the people abducted from Africa to be sold were brought here – an estimated five million people; 400,000 went to the U.S. and Canada.

4. Because they were cheaper to purchase and replace, Brazilian slaves were treated worse than slaves in the United States.

The journey to Brazil was cheaper than the one to North America because of both proximity and wind patterns, which meant that the slaves were cheaper, too. Slave owners saw no point in spending money to feed their slaves well or care for them; it made more sense to work them to death and replace them. As a result, slaves in Brazil had dramatically shorter life spans than those who went to the United States. But they were essential for the development of the economy – the sugar plantations, the coffee farms, the gold mines.

5. Brazil was the last country in the world to officially end slavery

6. When slavery was abolished in 1888, blacks outnumbered whites in the country, so the government instituted “embranquecer”, a policy to ‘whiten’ the population via emigration of poor white Europeans.

The government actively discouraged their former owners from giving the slaves paid work, and launched an effort to woo poor white Europeans to the country as a new labour force – with the overt intention to “embranquecer,” to whiten, the population.

“The founding principle of the first republic was eugenics,” is Mr. dos Santos’s sardonic assessment. This was eventually enshrined in an immigration law that stated, “The admission of immigrants will comply with the necessity of preserving and developing, in the ethnic composition of the population, the characteristics that are more convenient to its European ascendancy.”

7. Samba and the Brazilian dance-fighting art of capoeira were both appropriated from black Brazilian slave culture.

Cornerstones of black culture – such as samba music and the martial art capoeira, practised in secret by slaves – have been thoroughly co-opted into Brazilian identity.

8. Brazilian favelas (or slums) were created because former slaves were denied the right to live in cities.

9. Black and mixed Brazilians earn less than white Brazilians, and are severely underrepresented in government and business.

Even after those 13 years of rapid change, black and mixed-race Brazilians continue to earn far less than do white ones: 42.2 per cent less. More than 30 per cent fewer of them finish high school…

At the last census, in 2010, 51 per cent of Brazilians identified themselves as black or of mixed race. But the halls of power show something else. Of 38 members of the federal cabinet, one is black – the minister for the promotion of racial equality. Of the 381 companies listed on BOVESPA, the country’s stock market, not a single one has a black or mixed-race chief executive officer. Eighty per cent of the National Congress is white. In 2010, a São Paulo think tank analyzed the executive staff of Brazil’s 500 largest companies and found that a mere 0.2 per cent of executives were black, and only 5.1 per cent were of mixed race.

10. Interracial marriage in Brazil often consists of higher status blacks marrying lower status whites/morenos (brown-skinned Brazilians) to produce lighter children.

Even interracial marriages are not the tribute to colour-blindness that they might appear to be. Disaggregate the data on who is marrying whom, and they show that such marriages are least common in the highest (predominantly white) income brackets, and most common among the lowest earners, who are almost entirely black or of mixed race. Carlos Antonio Costa Ribeiro, a white sociologist at Rio’s State University who studies race and economics, describes it as a sort of bleak bargain: When such marriages do occur, the darker-skinned partner usually has a higher level of education or a higher income or both. The relationship, at least on one level, is an economic transaction – each person is gaining social mobility, of one kind or the other.

11. Blacks who do manage to succeed in society are often re-cast as moreno or white. Their success ‘whitens’ them.

There is also a sort of alchemy, Prof. Ribeiro explains, by which people with a mixed racial heritage who succeed in business or politics, such as billionaire media magnate Roberto Marinho, come to be viewed as white. Even in the two fields in which black Brazilians succeed at the highest levels – sports and music – that alchemy can work its dark magic. Soccer phenom Neymar da Silva Santos Jr., who presented as black when he first began to attract attention on the pitch, has, with his ascendancy, become in the popular perception, if not white, certainly not black.

12. Blacks sometimes think of themselves as ugly.

“I wish I looked like you,” the five-year-old says. “I wish my skin was like yours; your skin is beautiful.” Her mother gently corrects her. “I tell her, ‘My skin is ugly. This colour is ugly.’ ” … When she was growing up, her mother, who is white, said things such as, “I found you in the garbage.”

“She didn’t say it in a mean way, exactly,” Ms. de Araújo says. Yet her mother never made comments like that to her sister. “I always wondered if it was because my sister was older, or because she was lighter,” she recalls. “I believed I was the worst of the worst, the ugliest. I believed everyone was looking at me.”…

Ms. de Araújo is close to her aunt, Simone Vieira de Lucena, whose skin is as dark as hers, and who grew up, like Daniele, as the darkest of her multihued siblings. Ms. de Araújo often uses the family nickname for her: Neguinha.

“I’m the darkest – so they always called me that,” says Ms. de Lucena, 42. When she was a kid, she says, her sisters told her that someone with her nose, her hair, could not hope to find a husband. The idea took such firm hold that she would not let anyone take her photo until she was in her 20s… She and her niece refer to each other as preta, black, sometimes, instead of by name, and Simone calls her best friend, whose skin is darker than hers, macaca (monkey) or fumaça (smoke). They do it, Simone and Daniele say, with complete affection. “It’s different,” says Simone, “when it’s between us.

13. It is considered impolite to refer to people as black.

…among strangers, it is polite to describe colour by using a word that implies lightness: Call the person you’re looking for morena, not negra, even though her skin is black.

14. The introduction of affirmative action at public universities in 2004 was largely met with resistance.

Brazil has two kinds of universities: There are private ones, which are either exceedingly expensive or of very poor quality. And there are public ones, run by the federal and state governments, which tend to be of a much higher calibre – and are free. But because competition for spots in the public schools is fierce, only applicants who have had a private-school education, and the benefit of months or even years of private coaching for the entrance exam, can pass the entrance test.

But in 2004, UFBA introduced a new policy: 36 per cent of seats would now be reserved for black and mixed-race students. For years, black activists had been targeting the universities, as the ultimate symbols (and purveyors) of the elite, for a first effort at affirmative action. In 2002, university administrations began to adopt ad hoc strategies, reserving spots for non-white students. The quotas, as they are baldly called here, applied to every faculty, but they had an outsized impact on the prestigious schools of law, medicine and engineering, which, even in majority-black Bahia, had long graduated all-white classes, year after year.

The quotas pushed the normally veiled discussion about race in Brazil into the open. Students and faculty staged large, angry protests against them. Television news programs showed weeping white mothers describing how their children had prepared their whole lives to follow in their parents’ footsteps but suddenly were being denied their birthright. The harshest critics of affirmative action insisted the policy was introducing racial discrimination into Brazil – rather than working to mitigate it – simply by noting the very existence of a hierarchy between the races.

15. Brazil has little black business or culture infrastructure although this is slowly starting to change.

“There’s no black radio or TV and there’s one magazine with a circulation of 40,000 copies. Second, economic power – we don’t have economic power in this country. Because of segregation, they had it in the U.S. – in a strange way it was helpful. There had to be black lawyers, black doctors, there was a black Wall Street in the 1950s. You can’t have black media or black education, with private schools to teach the history [like the U.S. had], if nobody has any money.”

16. Like the United States, Brazil has high rates of police brutality against black men.

Rio’s military police killed one out of every 23 people they arrested in 2008, the year they launched a “pacification” program in some favelas, ousting gangsters and installing military police units with new training in community policing. (The comparable figure for the United States is one in 37,000.) The number of people killed by police has since fallen dramatically in pacified areas: While in 2008 police killed 122 people in alleged conflicts in pacified favelas, in 2014 they killed just 10. However, less than a third of favelas have been pacified and, in the city as a whole, the number of people killed by police increased by 25 per cent from 2013-14.

17. Despite all this the number of people who identify as black in Brazil is rising, as black pride starts to take hold in the culture.

For 130 years, Brazil’s census data showed one steady trend: Every time the government counted its citizens, more of them were white. The successive waves of immigration played the biggest role in this. But so did a less tangible process: the slippery business of “passing,” through which mixed-race people took on a white identity.

And then, in 2010, came a change that startled demographers. For the first time since the slavery era, there were more black and mixed-race Brazilians than white ones. The census enumerates adults, so the birth rate doesn’t explain the change – and in any case, that rate is nearly equal across races.

Something else is going on, says Sergei Soares, who heads the national Institute For Applied Economic Research. It’s a shift in self-identification. “You could say that what’s happening is not that Brazil is becoming a nation of blacks, but that it is admitting it is one,” says Mr. Soares, who is white. There has been a black movement here since before the end of slavery, but it has never been influential. With the end of two decades of military dictatorship in 1985, however, there began to be new space for debate about rights.

>via: http://blackgirllonghair.com/2015/08/16-harsh-realities-of-being-black-andor-mixed-in-brazil/