SAN FRANCISCO

ART EXHIBIT

“THE BLACK WOMAN

IS GOD”

TURNS THE HISTORIC

DEVALUATION OF

BLACK WOMEN

ON ITS HEAD.

by Sheila Bapat

This moment is fraught. Racial strife overwhelms the heart. In this moment, bearing witness to transformative art is a way to open our minds, strengthen our souls, and move us forward toward racial justice. One San Francisco art exhibit is accomplishing exactly that.

On Thursday, July 7, The Black Woman is God: Reprogramming That God Code launched at SOMArts in downtown San Francisco, and it will be on display through August 17. The installation features more than 60 Black women artists’ depictions of Black women as deities. The July 7 kickoff included artists, dancers, and musicians performing inside the spacious SOMArts gallery to celebrate the exhibit and its assertion, The Black Woman is God. At the launch, San Francisco and Oakland-based curators Melorra Green and Karen Seneferu discussed the recent rash of police violence in Black communities in their opening remarks and noted that through coming together, we can move humanity forward.

But the need for this particular exhibit extends far, far beyond this current moment. As Seneferu’s website notes, “The Black woman’s contribution in the society has been devalued. She has been viewed as second-class citizen, relegated to the dresser draws of history. However, she has shaped and changed the world in social and political spheres.”

The exhibit intentionally turns the historic devaluation of Black women and their contributions—social, political, economical—on its head. This exhibit asserts Black women’s power and beauty and does not seek to devalue any other group in the process. I write primarily about women’s economic status and the exclusion of women of color from basic labor laws, and the concept of The Black Woman is God is deeply relevant. It applies pressure to the beliefs and values undergirding the laws and policies that exclude Black women’s lives from economic policymaking and their labor from economic value and protection.

In particular, domestic work—caring for children, elders, and homes—has historically been rendered invisible in U.S. law and excluded from basic legal protections. The United States’s earliest laws designed to protect laborers, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which codified the minimum wage, and the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which protected collective bargaining activity, were both enacted in the 1930s. Both laws excluded domestic work from economic protection.

When slavery was legal, many Black women slaves were confined to cleaning and cooking and caring for slave owners’ homes. The devaluation of domestic labor through legal exclusion is indeed a legacy of slavery and a result of sexism: Southern legislators refused to support these 1930s laws unless they did not include domestic workers, who, in the South, were still predominantly Black women.

Even today, Black women’s lives are not prioritized in our economic policymaking. As Angela Glover Blackwell wrote recently in Yes! Magazine, a critical strategy for achieving gender equality in the workplace is to invest holistically in communities where women of color live and raise their families. Accessible and affordable transit and fresh and healthy foods for the communities where women of color live are not invested in and are underutilized in economic policy. She asserts that “the roots of workplace inequality run deeper than…workplace policies…the realities of living in disinvested communities can put low-income women and women of color at a disadvantage before they even enter the workforce.”

And labor union leadership still does not include enough women of color. A reportfrom the Institute for Policy Studies published in 2015 notes that “[I]n 2014 black women accounted for 12.2 percent of union membership compared to 10.1 percent for white women, 8.9 percent for Latinas, and 11.8 percent for Asian women. However, in no union are the leadership demographics for black women representative of the union’s membership demographics.” Black women comprise the rank and file of unions and yet they are not the leadership face of the unions.

Economic policy and labor activism requires that we make Black women’s lives a focus. But meaningful economic and social policy changes in these areas also require that the persistent devaluation of Black women in our culture be transformed — which art can help achieve.

“Mother is known as the caretaker. If children aren’t cared for, we say, ‘Where is their mother?’” Green told me. “We need to view women as mother of civilization, too. If we as Black women know who we are, if we know our greatness, this world would be different. The imbalance of haves and have nots would be different.”

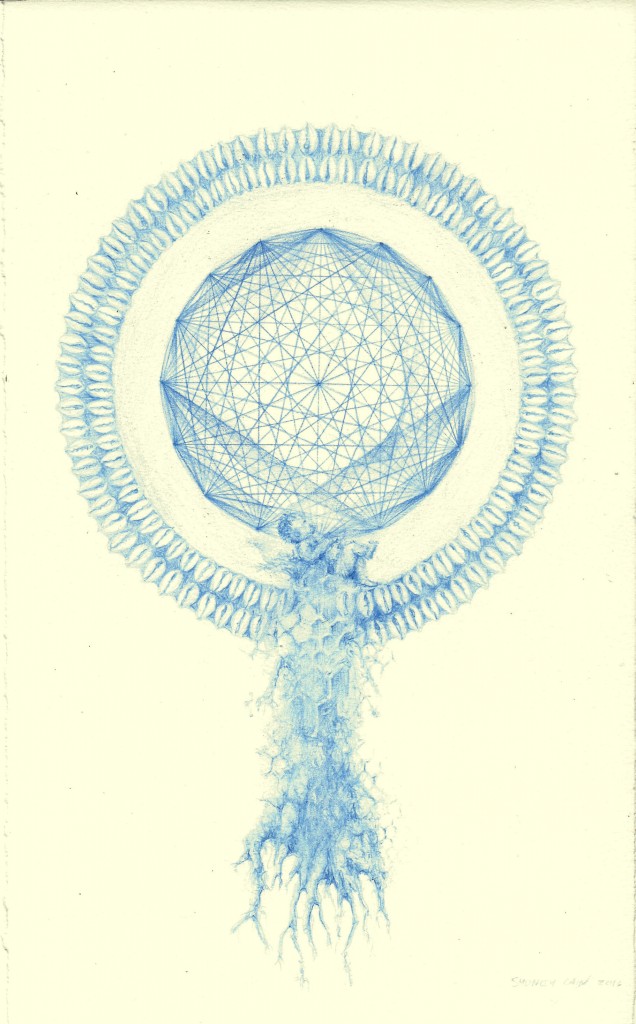

The power of art helps us envision a new reality and can drive our thinking about what the world can and should look like. For example, artist Nicole Dixon’s piece Transmission addresses the “need to pass down ancient knowledge from the powerful archetype of the Black woman to the next generation.” Dixon’s mixed-media technique layers drawing, painting, fabric, paper, and natural objects.

“The statement The Black Woman is God and the truth of it is diametrically opposed to Black women’s reality and the way people see Black women,” Dixon told me. “Because of this exhibit, you can feel the energy and the truth bubbling up, the tension between the truth of The Black Woman is God and the lived reality.”

Artist Yasmin Sayed notes that The Black Woman is God exhibit embraces Black women’s ability to “dance in the…field of possibilities.”

Artist Toshia Christal has three pieces in the exhibit. She participated because of the power of collective action. “When we’re talking about economics and politics and justice, it is really a matter of coming together in the community to move forward together,” Christal said. “We can’t do it alone.”

Indeed, when Seneferu and Green conceived of this exhibit in 2012, Green originally proposed curating only Seneferu’s art. But Seneferu insisted on inviting many, many more women to participate.

The result is a truly moving collection with paintings, clay works, photographs, and mixed-media pieces decorating the walls of SOMArts. Together, the women crafted a collective assertion that helps reprogram Black women’s positions in politics and society.

According to Seneferu, spiritually is essential to political transformation. “Spirit drives politics,” Seneferu told me. “Spirit has to be embedded in the politics. The root of this exhibit is transforming the spirit and claiming the Black woman as God. Recognizing that if [the] Black woman, who has been most dehumanized, can be viewed [in a] spiritual way, that creates space for all oppressed groups to do the same.”

Activists fighting for both racial and economic equality are invoking God into their organizing in various ways. For example, Alicia Garza is a cofounder of #BlackLivesMatter and special projects director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), one of the leading organizations fighting for women’s economic equality. Garza’s Twitter handle is Love God Herself.

Recently, a photo emerged of activist Ieshia Evans in a one-woman standoff with police during a protest against police violence. Evans later wrote on her Facebook page: “This is the work of God….I am a vessel! Glory to the most high! I’m glad I’m alive and safe.”

The Black Woman is God exhibit seems to encompass the way in which spirituality already is influencing activism. The installation will be at SOMArts, a gallery in the South of Market (SoMa) region of San Francisco, through August 17. This gallery is led by Maria Jenson, the gallery’s first African-American executive director.

“It is said that timing is the key to everything. And the timing of The Black Woman is God happened at the nexus of a series of profoundly tragic events—more police shootings,” Jenson said. “Countless people arrived to opening night [of this exhibit] with heavy hearts but ended the evening with spirits lifted. Art has long served as a response to social issues, providing perspective and healing, however, the artwork on display in the BWIG exhibit is also celebratory, a soulful reminder of the power of black feminine essence.”

The Black Woman is God is emerging as a movement of its own. Green and Seneferu plan to organize The Black Woman is God exhibits nationally to invite more communities to share in the concept. Building The Black Woman is God movement is critical for Black women, their families, and their communities.

“We have camera phones showing us publicly being killed, and nothing is being done on a large enough scale such that enough is enough?” Green said. “I would like to assert that a conversation about the Black woman being God is a huge force to be reckoned with. We are still treated as second-class citizens.”

“But if you can find beauty in each piece of art that comes from inside of each of those artists, that can signify and validate all of our beauty.”

+++++++++++

Sheila Bapat is an attorney and writer focusing on gender and economic justice. Her first book, Part of the Family: Nannies, Housekeepers, Caregivers and the Battle for Domestic Workers Rights was released by Ig Publishing in 2014.