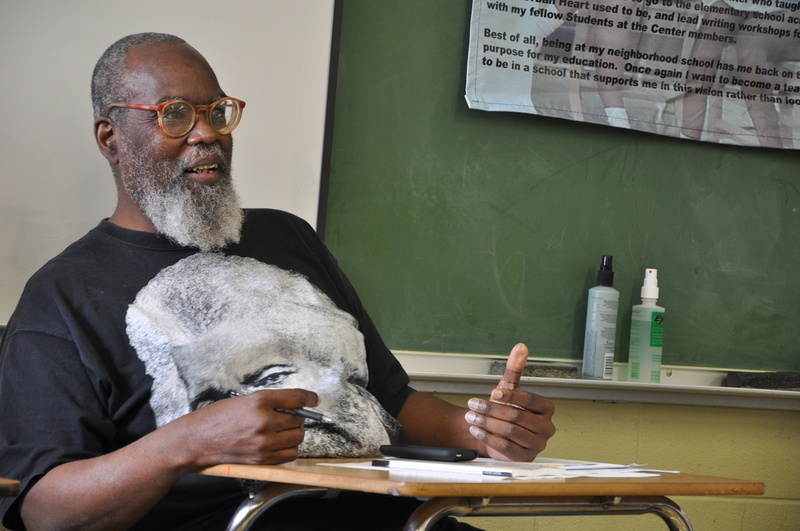

Interview with Award Winning

Neo-Griot Kalamu ya Salaam

[Rudolph Lewis, publisher of Chicken Bones, interviews

Kalamu ya Salaam circa 2003. The entire interview plus

most of Kalamu’s writings referenced in the interview

are available on Chicken Bones

>http://www.nathanielturner.com/kalamuinterview.htm]

1

NOMMO Literary Society

Rudy: Kalamu, I’d like to begin our talk with a discussion of your work with the NOMMO Literary Society. How do you keep the Society together? How do you keep the poets coming, working seriously on their writing skills?

Kalamu: I don’t. Folk either want to come and do so or they don’t. What I do is be very consistent. Except when I am out of town, every Tuesday I am there. I have a magnificent library of both books and music as a reference to help writers develop. I also assist in pointing people toward publishing opportunities.

Rudy: In your direction of NOMMO, what approach do you use? I mean how do you get a young writer to reconsider their topics or techniques? Do you sometimes shoot from the hip and say that’s crap, that’s not fully baked, or say go back to the woodshed with that one?

Kalamu: My approach is to offer a wide array of examples and influences. As to how effective I am, I think some of the members can answer that far more accurately than I can. There is no formal membership. Folks come and go. It’s wide open.

Our three-part format is 1. collective study, 2. announcements (which we call housekeeping), and 3. reading of original work and receiving of feedback. Generally, I am responsible for selecting what will be the subject of the collective study. Whatever it is, we take turns reading aloud and then discuss what we have read. This way we ensure a minimum common level of information.

The pieces range from formal studies of writing to creative work to essays about various topics. Less than 25% of what we study is specifically black-oriented. Announcements usually take only a few minutes. Reading original work and receiving feedback varies based on what folk bring to the table. In general, we are brutal with ourselves in giving criticism to regular members and very, very considerate of new members. We generally have more prose writers than poets per se. I think that is because NOMMO emphasizes “writing” rather than “reciting.” Performance is seldom the focus of any of what we do. As a result, the young poets who pass by from time to time don’t usually stay for any extended time.

As for telling folk what to do, or what to write, or how to write, I freely give comments, but I am not the only one and I am careful to make sure that the comments of others are valued. Plus, our associate workshop director, Paulette Richards, is a Ph.D. who teaches English and creative writing at Loyola University. Other dynamics of our workshop are covered in an introduction I have done for the next collection of workshop writings, “Speak the Truth to the People.”

Rudy: Is your work with the Society related to your teaching radio production and digital video to high school students? Do you find recruits for the Society among these students?

Kalamu: So far, there has been no overlap between the students I teach at the high school level and the NOMMO workshop. I have been teaching in the “students at the center” program for four years now. It is a learning process for me, a major learning process. Learning to teach what I know. Teaching has forced me to conceptualize and organize my information so that I can share it. I do very little recruiting for NOMMO.

Actually, I am not trying to increase the size of the workshop. We have a steady, core group of five to six writers and that seems to work well in terms of development. And from year to year there is always a turnover. Some folk moving on, new folk joining. Oh, one other thing. There are a couple of folk I mentor long distance via the internet, telephone and occasional in-person get togethers. Those are exceptions. And I certainly don’t want to take on any more. But that is another aspect of what I do.

Rudy: I still do not have a clear picture of the writers who are members of NOMMO. I assume they are all black. When you took me to a poetry set one night in New Orleans, I assumed some of those young people were in your group. Were they? How would you characterize those who are in NOMMO? Who are some of the writers who are now in NOMMO, who have passed through NOMMO?

Kalamu: If I remember correctly, only one of the writers you heard that night was a NOMMO member. Yes, NOMMO is a workshop for Black writers. At least 75% of our writers are female, and the majority are in late twenties to mid-thirties. Our youngest member is Sukari Ua, she is a 16-year-old high school student. I am currently the oldest at 55. We have a couple of folk in their early 40s. Some of our writers are self-taught, as I am, and others are formally trained.

We don’t have any writers who have made a big splash nationally, although a number of our writers are included in recent anthologies such as Role Call, Step Into A World, the Def Poetry Jam anthology, and E. Ethelbert Miller’s new anthologyBeyond the Frontier, as well as Afaa Weaver’s new anthology about African American families (due out in August 2002) [These Hands I Know]. Freddi Evans, one of our older members, both in terms of age and in terms of how long she has been in the workshop, recently published a children’s book [A Bus of Our Own] that won a major award. We plan to publish a second book by Freddi, the History of Congo Square.

Rudy: NOMMO is more than just a group of people. You have a place, a building in the middle of the community that is emblematic of a poetic, writing activity that goes on. Can NOMMO be duplicated in other cities? Does it need someone like Kalamu ya Salaam to make it work, long-lived? Do you think NOMMO will exist beyond you? Has NOMMO been duplicated in other cities?

Kalamu: Can NOMMO be duplicated as a writing workshop in general, yes; in particular the way we do it, probably not. Yes, our approach needs someone to take the responsibility of setting up a literary liberated zone, collecting and maintaining a library of books and music, and having the patience to work at the same project for five or ten years without getting tired. I have not even considered trying to duplicate NOMMO in another place. On the other hand, I hope that we can serve as an example to others and, in fact, be surpassed by what other folk are doing.

[NOMMO ended when Katrina hit New Orleans. We were set to celebrate our 10th anniversary in September 2005. Katrina happened August 29, 2005. —kalamu]

12Dec2015 – mini-reunion Nommo Literary Society— with Freddi Evans, Jarvis DeBerry, Kalamu Salaam, Nadir Lasana Bomani, Mawiyah Kai EL-Jamah Bomani, Marian Moore and Kysha BrownRobinson at Community Book Center.

2

Changes in Literary Style & Mainstream Publishing

Rudy: From your poems “Iron Flowers” (1979) to “The Call of the Wild” (1998) or your present efforts has your own poetic technique or approach changed?

Kalamu: Not much at all. In fact, over the last decade I have been focusing on fiction and over the last three or so years focusing on video. I have not produced much (for me) poetry. Of course, I keep developing incrementally but there have been no major stylistic developments. In fact except for the formal forms of haiku and my investigation of 14-line, emotionally-led poems (variations of sonnets), everything I am now doing I was already doing with my first book.

The blues, jazz, narrative and political poems were established as my direction by 1969 with “The Blues Merchant.” I have great facility with poetry but writing poetry is not my main focus. In fact, because I have done so much journalism and critical writing, poetry has never been the main or sole focus of my work, and as a result, my attention to poetry ebbs and flows.

Rudy: When did you begin these formal experiments? I know that as early as 1985 you were writing haikus. You gave me one of them to publish in Cricket, my short-lived poetry journal. It was “Haiku No. 30.”

| Haiku #30 Swabbed in sweat drenched blisswe answer gregg’s cornet with butt shaking footnotes |

Rudy: As I recall, you set as your task to write one hundred haikus and publish those as a book of poems. What became of that project? You have continued to work with the form.

Kalamu: Oh, I started this particular wave of haiku writing around 1985. Investigating haiku was a byproduct of me trying to come to grips, emotionally, with me leaving my marriage and the subsequent divorce. I have written about myself as a poet, a poetic autobiography of sorts, that was published by Gale Research as part of their ongoing writer’s autobiography series. They asked for a longish essay up to 10,000 words. I gave them a small book of about 47,000 words. They published the whole thing Art for Life: My Story, My Song. A lot of information is in there.

After the poetry-autobiography–I call it “poetry-autobiography” because it only talks about my work as a poet and does not go into any of my other writing or any of the other activities I have been involved in over the years. After that came out, I went on to write a short essay about my approach to the haiku. Based on the haiku section of the autobiography, that essay [On Writing Haiku] has been published a number of times including in Warpland, the literary journal out of Chicago State University, associated with the Gwendolyn Brooks Writers Conference.

As for the haiku project, I completed the manuscript. Have written over 200 haiku. Just never tried to get it published and was not that interested in publishing it myself. Two aspects about me and publishing that are relevant here.

First, I have never strongly desired to publish with an establishment press. The lack of a book by a mainstream press is one reason my work is not more widely known. I never wanted whatever success or relevance I achieve to be based in whole or even significantly on my association with the mainstream. That means I will most likely be on the periphery of publishing and popularity for the rest of my life.

At the same time, I don’t want to give the impression that I would not publish a book with a Random House or whomever, because if the conditions were right, I certainly would. It’s just that I am not too inclined to try and make it happen. I won’t put any significant energy into pursuing mainstream publication.

Let me tell you two little stories that illustrate my point. The first is from 1967. I was still in the army, stationed at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. I sent a manuscript of short stories, my first short story collection, to three companies. I believe it was Knopf, Dial, and William & Morrow because that’s who published Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and LeRoi Jones. Charles Harris, an editor at Morrow whom I got to know some years later, sent me a letter in response to my submission. He said that they would be interested in the stories if I would add a couple of stories to fill out the time line.

The collection was basically linked short stories about a young man dealing with social pressures and trying to decide what he wanted to do for a living and whether to marry his girl friend and start raising a family. Most of the stories take place in roughly the same time period except for the last story which jumps about 40 years and takes place at the man’s funeral. Harris was asking for a couple of stories to bridge those years. At the time I thought he wanted me to do something I didn’t want to do. I thought he wanted me to write some other kinds of stories. I never even responded to Harris’ letter. After I got out the army, I joined the Free Southern Theatre [FST] and turned away from fiction.

Before FST, I was writing fiction and poetry. After FST, I wrote mostly drama, poetry and journalism. The journalism happened because I was a founding member of The Black Collegian Magazine in 1970. But my point is, I was too ignorant and too maladjusted to take advantage of a major publishing opportunity. I don’t want to give the impression that the reason I don’t have a book with a mainstream press is solely because of some kind of ideological purity.

At different times, I have worked with literary agents or submitted material, but for various reasons it did not work out. I can get individual pieces published almost anywhere because I know how to write well and I have something to say, but when you consider a collection of my writings, well, inevitably I offend the powers that be. And being on the outside does not bother me because, as I have written elsewhere, only a Negro wannabe is worried about offending our oppressors and exploiters, worried about whether the people who maintain the mainstream will accept our work.

On the one hand, there is an essential opposition to the status quo, but at the same time, I know there is also some social maladjustment on my part. I can be difficult, very difficult to deal with. A lot of it has to do with my personality, my likes and dislikes, my understandings and ignorances. I just don’t like the mainstream. Period.

In fact, beyond my political disagreements, there are stylistic things I do which I know offend certain sensibilities. Although I try not to offend gratuitously, at the same time I know myself and I know my various audiences. I know some people react negatively to certain words, phrases, images, ideas; well, if those people are mainstream people, sometimes I use words and ideas that are offensive to them as a way of making my opposition clear. Plus, there is this New Orleans thing, where we will do some weird shit just to clear the air, to send the squares home so we can go on and get down.

The second story is recent. About a year ago, the director of a major university press contacted me and asked me to submit some material. I still haven’t sent them anything. Mind you, I have all kinds of manuscripts sitting around. A travel book, at least three collections of short stories, all kinds of poetry manuscripts, a science fiction novel that is half finished (it probably won’t ever be finished because I am not that interested in the novel as a form), two photo and essay books that use the work of New Orleans photographers, so forth and so on. But, you know, it’s just not part of my nature to give the white establishment anything but my undying contempt.

I know that not every individual who works in the establishment represents the establishment views, and I know that much of my work could find a home there if I really worked at submitting it, but, fuck it, that’s not what I am really interested in doing.

Other than my avoidance of publishing with the status quo, there is a second factor, namely the lack of major Black publishers in general and for poetry and fiction in particular. One reason there are so many self-published poets and fiction writers is because there are so few, literally only a handful, of Black publishers who deal with poetry and fiction.

Bear with me—I know this all seems a long way away from responding to the question of haiku, but I don’t think we can achieve a deep understanding of anything until we understand the context. Because we as African Americans were stripped of much of the material representations of African culture, most significantly of all, stripped of African languages—and you do know that language is both worldview and self-concept—because we were forced to use non-African forms and modalities of self expression, in order for us to maintain some sense of our own humanity we had to not only alter the content of what we put into the foreign forms that we were forced to use, we had to also alter the forms themselves so that those forms could fully represent us.

In America, our humanity has always been one of opposition to the status quo as long as the status quo was based on exploiting and oppressing us. That remains the case, it is just that the form of subjugation is no longer predominately racial in tone. Today our subjugation is environmental, gender-based, and economic in it’s major manifestations. By environmental I mean what most people mean but I also mean something more. We live in areas of environmental neglect and toxicity.

Additionally, from the standpoint of the social environment, whether you talk about education or health, access to transportation or recreation, we are at the bottom of most indexes. This is the basis of what I call an oppositional mentality. We are opposed to the conditions under which we are forced to live.

Here is the leap in my thinking: I believe this oppositional mentality also functions in the area of the arts and manifests itself in our always coming up, not only with new and interesting things to say, but also coming up with new ways to use existing forms and technology. We are innovators precisely because it is only through innovation that we can fully express ourselves and only through innovation can we mitigate, if not outright obliterate, our contemporary second class status and the debilitating legacies of our historic enslavement.

I don’t think most artists think of this consciously, but I think almost all of the Black artists we revere have de facto altered the cultural landscape, created new forms, and offered fresh insights. I never was interested in writing haiku like the masters of the form. What I was interested in was mastering the form so that I could use the form to say what I wanted to say in the way I wanted to say it. Finally, I have not continued to explore haiku. Occasionally, I will write a haiku, but it is not something that I am committed to working on in general. I’ve been there and done that. I can still do it, if I want to, but right now I want to do other things.

3

Borrowing & Adapting Literary Styles

Rudy: I assume you were first influenced by free verse, working without rhyme schemes, which itself is an artificial form. These forms set boundaries. They restrain expressiveness; some forms restrict thought much more so than others. Whether it’s iambic pentameter, alliterative verse, consonantal verse, Petrarchan or Shakespearean sonnets, or the exaggerated rhythms of Gerald Manley Hopkins, there is something unnatural about such forms.

I know McKay used the sonnet to great effect. He pressed effectively against the boundaries. Wright experimented with haiku. But his haiku are just a curiosity. They have had little influence. I read a book of poems by Sonia Sanchez in which she experimented with formal verse. I don’t recall the name of the form; it may have been a European form. I don’t recall. Do you know the book I am talking about? I thought she handled the form well. But I am not sure that the overall effect was meaningful. The natural expressiveness we usually associate with her seems to have been overly curbed.

Haiku is not natural to English. It is Oriental, coming from an entirely different cultural perspective. It is more radical than the Italian sonnet was in English. Note even Shakespeare had to change the form to make it work. Even rhyming is not natural to English, which tends to accent the consonant rather than the vowel. So why then the haiku? Could you talk about the reason you have chosen to work with formal verse and have continued to work with this form. Isn’t all that a step backward?

Kalamu: I think in some ways I answered some of these questions when I responded about haiku, but there are other interesting notions you raise.

First off, I started off attracted by rhyme. Remember that Langston Hughes was my first and most lasting influence. Remember that I was taught Paul Dunbar and James Weldon Johnson in public school. We recited their work in class, at assemblies, at public programs. Although I did not at the time think of all of this as poetry; nevertheless, those poems that heavily employed rhyme were my introduction and that is what I liked.

After Dunbar/Johnson/Hughes my next major influence in writing poetry was Carl Sandburg in high school. Next was e.e. cummings. And third, and more important than either Sandburg or cummings, was Black beat poet Bob Kaufman.

In hindsight, Sandburg was an extension of Hughes, however, I have not gone back to Sandburg since high school. I graduated in 1964, so that’s the last time I really read Sandburg’s work other than in passing. I never did get too far into cummings after the initial attraction. Kaufman, I continue to read. After those folk, there are no single influences that I can point out. Perhaps, someone who studies my work closely and asks probing questions might be able to come up with other influences.

Secondly, all art is artificial. All art is about a human being imposing a form on the raw materials of 1.) reality and 2.) one’s reactions (whether feeling or thought or both) to reality. All art. The question is what forms do you choose, or in some cases what forms do you use (even if you don’t consciously choose those forms). I maintain that we are predisposed to certain forms just by the weight of our childhood experiences, i.e., what we were exposed to as we learned to talk, walk, dance, sing and what forms were used when we received our initial formal education.

We are also predisposed by our genetic makeup, which is not to be confused with “race.” Genetics is a complex subject, but to reduce genetics to a shorthand for the sake of this discussion, we should be aware that individual personality traits such as temperament and attitude have genetic influences and are not simply individual responses to environmental stimuli.

The material/social environment on one hand and the individual response to that environment on the other hand are the two poles across which sparks the flash of art.

You ask why do I choose to deal with haiku and sonnet. One response is, why not use haiku and sonnet? As far as I am concerned, the haiku and the sonnet are mine to use if I choose to do so. As a human being, all of human culture is available to me.

For example, the whole of English literary history is part of my heritage, an imposed part, but an essential part nonetheless. I can choose to oppose certain aspects of my cultural heritage but I, as a conscious and political artist, can not ignore a major aspect simply because I don’t like it or because it represents the viewpoints of the master. The truth is, the master’s views are too often also my views unless and until I create different views and institute those different views.

From a revolutionary perspective, it is not enough to simply think about things. The material and social institution of revolutionary views is essential. Without creating a culture of our own, we invariably will be re-defined by the culture of others, and mostly the others who dominate us. But the revolution is not to separate us from the world. The revolution is to enable us to participate in world affairs and to contribute to world culture as whole and healthy human beings who are able to enter into reciprocal relationships with other cultures.

I take my cues from Black music. For the purposes of this discussion, let me use the example of jazz music, both in terms of forms and in terms of instruments. The forms of jazz include both original and borrowed forms. Some of the music is highly structured (composed and arranged) and some of it is totally improvised. Some forms such as the western musical scale are of European origin and others forms such as the “blue note” are of African origin. What makes jazz distinctive is not the forms per se, but the way in which jazz musicians used various forms.

Coltrane played “My Favorite Things” and in the process revolutionized jazz. The Coltrane revolution was not based on the European form but rather was based on what Coltrane did with that form. In a similar way, Coltrane played the tenor saxophone, a European instrument, but the way that Coltrane played that instrument revolutionized how every musician approaches the tenor saxophone.

Do we ask, Coltrane why were you playing an American pop tune rather than playing your own composition? Do we think Trane’s “My Favorite Things” is culturally unacceptable or that it is an example of Coltrane playing so-called “White music”? Do we say to Coltrane, why do you play a European created instrument?

I think— or, more accurately, I hope—when people read my haiku and my sonnets, they will see something very different from traditional Japanese haiku or Shakespearian sonnets. My goal is to use the forms in a way similar to how Trane used “Favorite Things,” simply as a vehicle to say what I want to say. Indeed, the haiku and sonnet traditionalists probably don’t think what I do is true to the classic haiku and sonnet forms, and they are right. Ultimately, I used those forms because I wanted to and because I could. Why? Well, like I said, why not?

I agree with Terence (the enslaved African writer from Roman history): there is nothing human that is foreign to me. I can learn and use any human cultural expression that exists; moreover, every human expression is part of my heritage. Or, to paraphrase African liberation leader Amilcar Cabral: we will be free only when we are both self-determined and are able, without inferiority complexes, to use any and all aspects of human culture that work for us.

I strive to be a revolutionary, rather than a racial or cultural chauvinist! The revolution is in actualizing self determination. We don’t necessarily have to use only those forms that we create. We can borrow and adapt, and in doing so, transform and actually create new forms out of those borrowings and adaptations.

I think a major part of what I perceive as the problem with the question you asked is an unnecessary dualistic approach to culture. Them and us. White and Black. Right and wrong. Yes, we need to create our own forms, which we have done, particularly with the blues in music and poetry. But we also can revolutionize pre-existing forms. My outlook is not either/or. We need both; we need to create and we need to transform, or revolutionize, pre-existing forms. Both/and, not either/or.

What is backwards is rejecting something simply because we did not create it. What is backwards is thinking that we have got to create everything ourselves. What is truly backward is assuming that human culture is not a shared culture, that somehow it is wrong for us to learn from others or to adapt forms that others have created.

On the other hand, I understand the importance of paying attention to our own creations and the importance of being grounded in our own culture. That is absolutely correct. We must be rooted in who we are. But, I believe, we must also embrace the whole world, or at least check out the world. You never know what might work for you.

I think the major problem has been not with our borrowings but rather with our ignorance about our own culture. I would have a real problem if I wanted to write haiku and sonnets but didn’t want to and, on a level of practical proficiency, actually could not deal with blues and jazz forms in literature. But, you know, I know what the mainstream knows, and I know my own culture.

Plus, I never borrow without adapting, without in some way either transforming the form itself, or transforming how the form is used so that the form that results represents me rather than is an example of me trying to be like those from whom I borrowed the form. I bet you don’t nobody think Japanese when they read my haiku, and for sure they don’t think iambic pentameter when they read my sonnets. But beyond that, you know that the bulk of my poetry is not in the haiku or sonnet form. The bulk of my poetry is blues and jazz based, clearly so.

Ultimately, it is backward for us to limit ourselves in any one way, whether it be only doing what we create or only doing what others create. I believe: we must be both rooted in the self as well as interested in the world.

###

>via: http://www.nathanielturner.com/kalamuinterview.htm