Every night of the week, and four times at the weekend, Lupita Nyong’o has been going on stage at New York’s Public Theater as the Girl, an escapee from a village in war-torn Liberia who finds shelter among the concubines of a warlord. In a relatively youthful career, it is the kind of role that Nyong’o is proving very good at – light-footed in the face of traumatic material – and the play, Eclipsed, by Danai Gurira, will move to Broadway in the spring. There are no men in Eclipsed and, Nyong’o says, “It’s rare that we have an all-female cast. And all-female African voices speaking for themselves on the stage. I don’t know any other play that does that. I felt it was something I needed to do.”

Nearly two years after winning an Oscar for her role as Patsey in Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, the 32-year-old says she had a lot of other options on the table; the decision to do a long run at a small New York theatre, rather than throw herself into a beckoning Hollywood career, is a sign of her priorities – and confidence. A few hours after we meet, in a photographer’s studio in Manhattan, Nyong’o is due at the theatre, and in these preparatory hours is quiet, composed – a leaver of pauses. She moves across the studio floor as if on coasters, and if she wasn’t made up fresh from the shoot, has the tiny proportions, cat-like eyes and perfect symmetry that don’t need much help to look magazine-ready. Since her Oscar win, Nyong’o has become a model for Lancôme, among others, something she regards with satisfaction. One of the best things about her recent success, she says, has been the extent to which, in her native Kenya, she is “a source of inspiration” for girls who might otherwise have thought acting and modelling weren’t options for them.

Nyong’o is still adjusting to her radical change in fortune, something vividly described by the chasm between the only two films she has so far appeared in. After making 12 Years a Slave, but before it was released, Nyong’o continued her apprenticeship with a tiny role as an air hostess in Non-Stop, one of those Liam Neeson vehicles in which he is either gurning and crunching his knuckles or flying through the air waving a gun, and in which Nyong’o had precisely one and a half lines. Her third film role, still heavily under wraps, will be as Maz Kanata, an alien character in the forthcoming Star Wars: The Force Awakens. (Journalists will not be allowed to see the film until next week. Recently, it was rumoured that her role had been cut in the edit, but the director, JJ Abrams, has strongly rejected this, saying, “The only rumour more ridiculous than Jar Jar Binks being a Sith Lord is that I cut Lupita Nyong’o’s performance because it wasn’t satisfactory. In truth, her performance wasn’t satisfactory. It was spectacular.”)

The question is how she managed to pivot the role of Patsey into a huge career launch and withstand the kind of pressure under which lesser novice actors might have buckled. It comes down to good sense and imagination, says Nyong’o, who, after growing up in the Nairobi suburbs, went to college in America. The trajectory of a girl from an elite Kenyan family to Brooklyn, where she now lives, via Mexico, Yale and Hollywood, is one that gave Nyong’o a certain amount of flexibility and willingness to suspend judgment. It also conferred what reads as a certain distaste for saying anything that might be construed as controversial; she is even reluctant to offer an assessment of the Kenyan national character – “oh no, I wouldn’t want to be the one to do that” – a diplomacy one imagines she learned from her politician father. She is one of six children, and her father, Peter Nyong’o, is a prominent politician who teaches political science at universities around the world; her mother, Dorothy, is managing director of the Africa Cancer Foundation. Both, Nyong’o says, encouraged their children to “find out what we were passionate about and try to make a living out of doing that.”

Still, the family’s inclination was towards rigorous academic pursuit rather than the arts, and it took Nyong’o a long time to figure out she wanted to go in a different direction. She attended a series of international schools in Nairobi, and when she was 16, her parents allowed her to move to Mexico to live with an elder sister for seven months and perfect her Spanish. Afterwards, she studied for a degree in film and theatre at Hampshire College, Massachusetts.

At no point during those years, Nyong’o says, did she have any real sense what she was doing with her life. But the American system gave her what she needed to find out: freedom. At Hampshire, she says, “there are no exams, no grades. It was a culture shock. I was used to a very structured school. I did the international GCSE and the international baccalaureate, and it took a while to adjust and appreciate [the American system]. And I did appreciate it, because I was very indecisive about what I wanted to do. I knew that if I was in a more structured environment, I would end up not taking the risks I was raised to take.”

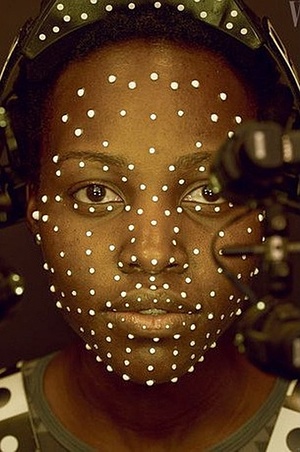

Those risks have led her to the Star Wars movie, for which she was covered in CGI tracking dots for most of her scenes. It seems a long way from the classical training she underwent during graduate school at Yale; how do you build character and motivation when you’re playing an alien?

“These worlds are created by human beings,” she says, “and at the end of the day they are created to illuminate something about us. So, under all the makeup, it’s just human relationships and wants and desires.” She laughs. “All we know is how to be human. And the way we take in the world that isn’thuman is also human.”

Nyong’o’s move from Kenya to the US gave her some insight into being a fish out of water, albeit one confined to this planet. Being in the US also made her appreciate what she had left behind; she realised how focused on western culture her education had been. “America has infiltrated all of us with its swag,” she says, laughing. “It took coming to America to make me realise the ways in which I was not American. It made me realise how much of myself and where I’m from I had neglected. That’s one of the reasons I took African studies while I was an undergraduate, because I realised I wanted to know a little more about who I was, aside from all that other stuff I had absorbed – not only from America, but from Britain. I grew up in a former British colony. So, coming to America, I realised it was the African influence I needed to familiarise myself with.”

At college, she began to think of herself as a film-maker, and for her final thesis flew back to Kenya to make a documentary called In My Genes, partially funded by her parents and focusing on the fascinating and often very difficult lives of black Kenyans suffering from albinism. It is a terrific film, a study in race and identity and the arbitrary nature of pigmentation. Nyong’o says it was a subject she identified with because she, too, had once been told she was the wrong colour – in her case, a casting agent who said, “I was too dark to be on TV.” She says, “to think that I was on the other end of the colour spectrum, when it comes to my complexion, yet we were experiencing similar discrimination. I think that’s what drew me to that subject.”

The casting agent was auditioning Nyong’o for a local commercial in Nairobi and the actor was horrified by what she said. “That was not fun to hear. But I just didn’t accept it. It hurt, you know. And I cowered. But I didn’t accept it, actually. That’s the truth.” The fact that she could, with some effort, shrug it off, is in no small part down to her mother, who “said you can do anything you put your mind to. It didn’t occur to me that I should change what I wanted to do. I needed to change how I was going to do it.”

Still, she looked around for role models. Oprah was one; the whole family would watch her talkshow while Nyong’o was growing up. “The overarching theme of her show is finding your purpose. That was huge.” What else? “The Color Purple was a huge influence on me. The closer I got to saying I wanted to be an actor, the more I started to look at which actors were doing things I was interested in and I admired. Charlize Theron and Cate Blanchett and Taraji P Henson. Elizabeth Taylor.” There is a long pause. “Oh, my goodness, whatsisface. Sidney Poitier was a very big influence on me.”

By the time Nyong’o graduated, she had started to lean away from documentary film-making and towards acting. While still a student, she had won a role in a Kenyan miniseries called Shuga and was convinced that, if she wanted to pursue an acting career, she should have some formal training. Rather than go to drama school, Nyong’o went to Yale to study acting as part of an MFA programme, a course most famously pursued by Meryl Streep; in the US, it is the acting course that comes nearest to the pedigree of RADA. During the vacations, she headed into a second season of Shuga, found a manager and, while still at college, was put up for the 12 Years a Slave audition.

Nyong’o was at an important junction when the role of Patsey came along; young enough to be bullish in the face of considerable pressure, old enough to have a firm sense of herself. “I felt comfortable in my own skin. Had I felt any other way, it might have been discombobulating.”

She had Yale to thank for this, she says, and also, one suspects, a certain level disposition evident in her long, thoughtful pauses and quiet demeanour – although it took her a while to get there. In 2005, when Nyong’o was an unpaid production assistant on the set of The Constant Gardner, which was filming in Kenya, she bugged Ralph Fiennes with questions to such a degree that, she has said, although polite, he eventually asked her to give him some “space”.

After Yale, however, Nyong’o had calmed down considerably. “I felt that I had just come out of a very rigorous training. I felt prepared. I also felt, psychologically, that one of the merits of going through an acting programme was that you work with your demons. You work through your self-doubt and learn how to make friends with it. And so when [a big break] comes along, it’s so easy to self-sabotage and say, I’m not ready. I felt like that a lot, but I would know that the next sentence is, ‘Breathe, it’ll be fine.’”

The other helpful element in her background was the fact that Nyong’o is not fazed by celebrity: in Kenya, her father is extremely well known, “a big public figure. And so I knew that the man sitting across the table from me was not necessarily the man on the cover of the newspaper. I grew up exposed to public persona versus private. I had no expectation that Brad Pitt would be anything other than a man. So of course there’s the nervousness, and the, oh my God! But there’s also a very healthy reminder in my system that these people are just people. I know the folly of not recognising that. I’ve seen people approaching my father with preconceived notions of who he is.” (Pitt is producing Americanah, the forthcoming adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel and Nyong’o’s first starring role.)

Filming 12 Years a Slave wasn’t easy. It’s a hard film, and the hardest scenes involve Nyong’o’s character, who is raped, beaten and abused by the plantation owner, played by Michael Fassbender, and his evil wife, played by Sarah Paulson. Nyong’o has talked about the discomfort, physical and emotional, of sleeping overnight in the complicated prosthetic back piece that depicted Patsey’s wounds after the whipping scene, but one wonders how she and Fassbender got through the filming of those moments together. “We spent a long time hugging. And we did a lot of dancing. We partied hard. It was really great. We both had a good in-and-out-of-character work sensibility. When we were in it, we were in it, and between takes would leave each other alone. It was like going into a boxing ring. We come, knock each other down, regroup, and at the end we hold hands.”

Her parents were disturbed when they first saw the film. Nyong’o says that her mother “didn’t talk about it with me for a while. And when she did, she was very mousy. She just said, ‘You did really well.’ But she was heartbroken. She was very quietened by it. Very moved.”

And her father? “My father, he’s a different kind of person. He said something…” There is a long pause. “He was at the premiere in London, and he said something funny to the effect of, ‘Why did you let them beat you like that?’” She laughs. “He also said that someone had asked him whether he could relate to the story, given his political past.” Nyong’o’s father once served as a minister and was harassed along with other family members for his opposition to Daniel arap Moi, the country’s president for over 20 years. Nonetheless, says Nyong’o, “he said that his life is like a dinner party compared with [12 Years]. There’s recognising that we are very privileged.”

One imagines that, to play the most brutal scenes, Nyong’o had to disconnect, but she says that isn’t a word that makes sense in the context. “Disconnection suggests that I can shut down and be someone else. I can’t do that. I feel like I use my personhood to do what I do. But it is understanding that it’s make-believe, and recognising that I have the privilege of doing this in a make-believe world, rather than having this be the truth of my life. And remembering that allows me to go for it with an open heart, because I get to walk away. Patsey didn’t get to walk away.”

The role Nyong’o is playing nightly on stage in Eclipsed touches on similar topics of trauma, enslavement and sexual violence. When she gets home to Brooklyn at 11pm, she watches mindless TV (the comedy Jane The Virgin is her current favourite) to relax. She hasn’t been back to Kenya for a while, but since winning the Oscar has been raised to the level of a national hero at home in a way that, she says laughing, is “quite spellbinding”.

What does she love about Nairobi? She thinks for a long time. “There’s a certain jive,” she says. “There’s a vibration when you spend time in a place. You absorb it and I know my Nairobi vibration. I love things like stopping by the side of the road at around four or five in the afternoon, when the roasted maize comes out. There are certain corners where you can find it, and there’s always discussions about where’s the good maize. The cassava chips. Things like that. I love the red soil.”

The fact that Nyong’o, in playing Patsey, was depicting a singularly American crime against humanity might perhaps have given her some distance on the role; some ability to regard it as a cultural outsider. Did she make a distinction in her own mind that, in this dreadful story she was telling, she was not animating her own nation’s history? “No, because at the end of the day, when I’m taking on a role, I’m taking that history personally. It’s got to be my history. And if I’d lived in Patsey’s time, I would have been in the deepest, darkest part of the cotton field. I would not have been spared. It may be distant, but it’s this close. It’s a history that affects America for sure, but we are not untouched.”

- Star Wars: The Force Awakens is released on 17 December.

Hair: Lacy Redway at the Wall Group. Makeup: Nick Barose at Exclusive Artists Management. Nails: Casey Herman at Kate Ryan Inc.

by

by