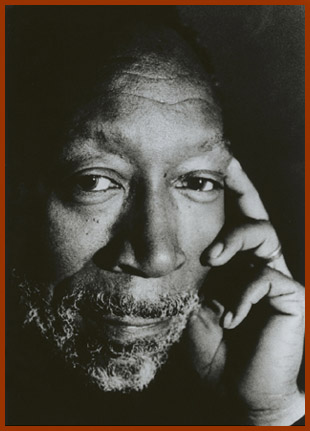

THE MAN

WHO WROTE I AM

I think art has always been political and has served political ends more graciously than those of the muses. I consider myself to be a political novelist and writer to the extent that I am always aware of the social insufficiencies which are a result of political manipulation. The greatest art has always been social-political, and in that sense I could be considered striving along traditional paths.

—John A. Williams

August Wilson was insistently whacking the dinner table. He had been at it for 47 times and still had eleven more thrashings to go. John A. Williams, sitting to Wilson’s left and beaming a small, self-effacing smile was obviously honored by Wilson’s animated response to Williams telling all of us sitting around the small table that he had submitted his new novel, Clifford’s Blues, fifty-eight times before finding a publisher.

“Fifty-eight!,” an incredulous August Wilson echoed, not sure that he had correctly heard Williams. When Williams confirmed that he had submitted the novel about a gay, black jazz musician interred in Dachau Nazi concentration camp to fifty-eight different publishers over a number of years before finally receiving an assenting nod, August Wilson stopped all conversation as he patiently began ticking off the repetitions while intoning the count in his resounding baritone voice: one, two, three, and so on, not stopping until the final hit, Fifty-Eight!

We were attending the Gwen Brooks Writers Conference at Chicago State organized by Haki Madhubuti and staff. August Wilson, born April 27, 1945 was only two years older than me. But John A. Williams was a master from an earlier era. Williams was born December 5, 1925 in Jackson, Mississippi.

Williams was the first novelist whose work fully engaged me in terms of my life experiences and aspirations. Indeed, while I was in high school, just when my interest in jazz was deepening, I encountered Williams’ 1961 novel, Night Song, which subsequently was made into a 1967 movie, ‘Sweet Love, Bitter’ starring Dick Gregory as jazz musician Richie ‘Eagle’ Stokes, a character based on Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker.

Like many writers of my generation, jazz was the artform that moved me the most. I wanted to be able to write with the innovation, intensity and impact of jazz musicians who were for me the leading artists of the sixties and seventies. While Night Song got my full attention, what really got all inside me was Williams’ 1967 novel, The Man Who Cried I Am. Black cultural twists on the existential questions of being and identity were deeper than simple reflections on racial bigotry. Williams wrote about the complex humanity of the black condition and not just the topical politics of African-American life and struggles.

While what it means to be black in america is a general preoccupation of 20th century black writing, male novelists seem almost compelled to deal with the difficulties of self definition. Initially published anonymously, in 1912 James Weldon Johnson dropped The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man; in 1952 Ralph Ellison kept us wondering as we tried to identify and identify with the nameless protagonist of The Invisible Man; in 1953 Richard Wright confounded many a reader with The Outsider after having enraptured millions with Native Son; Baldwin notably entered the fray with 1962’s Another Country, providing a veritable Rubik’s Cube of inter-racial/inter-gender juxtapositions in which everyone seeks to find theirself in the wake of the suicide of a black man. That’s just a quick handful of examples, but that search for manhood and self identity is a long, winding, and too often lonely road.

I read The Man Who Cried I Am as a young man, full of all the certainty about existential questions that only the young possess. I can not speak for everyone, but most of the black writers who are males and specialize in fiction whom I know of or whose work I have read, most all of them are swinging their pens at this elusive target. It is almost like we are blindfolded celebrants at a sixteenth birthday party trying our best to swat—indeed trying to bust, to destroy—the perpetual pinata as though it were a wasp nest that we could bat away and thus rid ourselves of the deadly stings of a vicious and racist society within which we were born, sort of like coming of age in a sacred circle of hell—it’s sacred because it’s not only our birthplace but belonging to this peculiar society is also our birthright, and it’s hell, well, because it is, our very own personal and public place of persecution.

I did not have to read anything more than the title to understand the profoundness of The Man Who Cried I Am; especially to grasp the multifaceted import of the verb in the title. Cry has so many meanings, so very many meanings, not the least of which is the paradoxical injunction commonly said to us, shouted to us, extorted, pleaded, you name it, constantly ringing in our ears: “a man ain’t suppose to cry.” And yet every African American man I knew, at some point or another must cry “I am”—or die.

Asserting one’s existence can easily get your ass killed if you are black and male. (Our sisters are also killed and imprisoned, but the routine with them is that they are exploited and sexually traumatized with the rapist and exploiters too often being men of color.) Making it in America, how soever one defines “making it” does nothing to alter that deadly equation of brutality and lynchings—ask President Obama, how come there are so many, publicized ritual murders happening now that a black man is president. Could it be that the police and others are engaging in a ritual slaughter of the “nigger in the white house”?

Williams novel includes the controversial idea that the government has prepared concentration camps for African Americans. What the mainstream dismissed as fantasy seemed to me a realistic possibility. In 1965 when I was in the Army one of my platoon buddies was a young soldier of Japanese ancestry. He had been born in a California interment camp during World War 2. After so many long, hot summers and the conflagrations that arose following the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968, the possibility of concentration camps for blacks seemed not only possible but probable to me.

Michelle Alexander’s 2010 publication The New Jim Crow struck a resonant chord. America leads the world in incarceration. Louisiana leads America in per capita incarceration. New Orleans leads Louisiana. Could it be that the prisons are America’s concentration camps? Is America’s penal system the fulfillment of Williams dystopian prophecy?

Most young men in this new millennium have never heard of, not to mention have not read, John A. Williams startling and perpetually relevant novel. Significantly the protagonist of the book is a writer. We writers spend a lot time, expend a ton of words, trying to explain ourselves to our audiences but actually to ourselves. We writers are trying to make understandable our very existence whether for the race in general or as an individual in particular.

It is said that on one of the ancient temples of Egypt an injunction is inscripted: know thy self. The graffiti scrawled on the soul houses of black males in America is the simple, confounding question: Who Am I?

When I met John A. Williams I was in my fifties. I had a biological father whom I revered and a close friend and mentor whom I sometimes refer to as a father-friend. Both of my grandfathers had been preachers: on my father’s side was what was called a jack-leg preacher, a man without church or congregation, and on my mother’s side, he was a pastor who founded two churches, one in the country side and one in the city. I did not lack for role models.

I left the church at fifteen (or thereabouts) and never looked backed. I peeped myself in John A. Williams. Actually, at the time I met him, I saw him as a grandfather figure. One of countless older black men whom the weathering of time and social battles had mellowed but never defeated. I never told him how much I admired his work nor did I attempt to stay in touch with him. But when I was in Munich, Germany in 1998, I was compelled to sojourn to Dachau concentration camp, the same camp John A. Williams described in his last novel Clifford’s Blues, which I enjoyed immensely.

John A. Williams has written both fiction and nonfiction; has published over 20 books both here and abroad. I try to avoid cliches, but in this case the cliche is correct: if John A. Williams were white, he would be celebrated and widely taught in high school and colleges, as are writers of far, far less accomplishments. The more I learned about Williams, the more I admired him. I should have bowed when I met him. He was a quiet, dignified elder/warrior. He had never wavered in the struggle, nor had he attempted to simplify or reduce our struggle to obvious, albeit wrong-headed, dichotomies of right and wrong, black and white.

John A. Williams was not only a socially conscious craftsperson, he was a meticulous and extensive researcher, and an elegant wordsmith. His deeply researched, historically accurate fiction and non-fiction holds up well because it is both factually accurate as well as artfully scripted. What we have in John A. Williams is a success at communication, if we would but read and reflect on what he was attempting to tell us. In America success is too often measured by popularity. Williams wrote fiction, journalism, essays, biographies, as well as edited anthologies. He now serves as a model of who and what a writer should be. My three early influences were Langston Hughes, LeRoi Jones (bka Amiri Baraka—like him I too had changed my name), and James Baldwin in that order. Currently, although I still very much admire my personal triumvirate, in my elder years I have come to respect and treasure the work of John A. Williams.

He not only stayed the course, but although he won a bevy of awards as well as authored numerous publications and related projects, unfortunately Williams remains relatively unknown and seldom celebrated. Regardless of how the world treats him/treats us, we should never forget. We should never forget who he is, never forget who we are. Indeed, to the degree that we do not know John A. Williams, to that same degree we men and women who are writers do not know the fullest reach of ourselves as voices who are crying in the wilderness; crying out both for self recognition as well as for the recognition of our people.

But regardless of how well he is or is not known, is or is not lauded, regardless, even in his obscurity John A. Williams is a resplendent example of a writer who confronted and answered that eternally perplexing question of “who am I?” While endeavoring to describe the enormous complexity of our being, Williams gave a profoundly simple, existential response to the ultimate query. Like god and nature, our existence is its own explanation: I am/we are. Being is definition. Our struggle as writers is to adequately give voice to the complexity of our simple response. Thank you brother John A. Williams.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Beautiful thought provoking tribute brother Kalamu. I feel compelled to revisit his work and read his entire oeuvre. Thank you.