JUL 03, 2015

Frederick Douglass’

Fiery 4th of July Speech

Unveiled in 2013, the 7-foot bronze statue of 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass looms large in Emancipation Hall inside the U.S. Capitol, a landmark constructed in part by slave labor. Douglass’ presence in the building seems only natural now that millions of Americans have come to recognize his heroic journey from slave to statesman, and the contributions he made to ending America’s original sin. But that was not always the case, and, on July 5, 1852, the larger-than-life figure stood within another hall — Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York — facing an audience, and a nation, very different from those who gather in the Capitol today.

A gifted orator, Douglass wanted more than to convince the crowd of hundreds gathered to celebrate Independence Day about the hypocrisy of slavery. He wanted, as James A. Colaiaco writes in Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July, “to sting the conscience of America.” Douglass did not mince words. “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine,” he would tell those assembled. “You may rejoice, I must mourn.” And he was just getting warmed up.

Much as one wonders what the White House Correspondents’ Association was thinking when it invited comedian Stephen Colbert to address its annual dinner in 2006, one wonders what the good citizens of Rochester were expecting when the outspoken Douglass took the podium in Corinthian Hall. At only 34, Douglass was arguably the city’s most famous resident, and he was well on his way to becoming, as Colaiaco puts it, “the most famous black person of the nineteenth century.”

When Douglass was asked to deliver the celebration’s keynote address, about 3.5 million African-Americans were still enslaved — roughly 15 percent of the U.S. population. A slave for the first 21 years of his own life, Douglass had founded The North Star, a leading abolitionist newspaper. The great contradiction between the ideals proclaimed by the nation’s founders and the human rights denied its black citizens lay at the core of his life and work, and he was not going to put the matter aside, even for the Fourth of July.

Independence Day was not regularly celebrated in the U.S. until the early 19th century, but by 1852 it had become what it remains today — a celebration of America’s “civil religion.” That year July 4 fell on a Sunday, so most Independence Day ceremonies like Rochester’s were held on July 5, though they too resembled a church service. Only after a local reverend led those assembled in prayer and read from the Declaration of Independence did Douglass take the stage to deliver a speech now known as “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

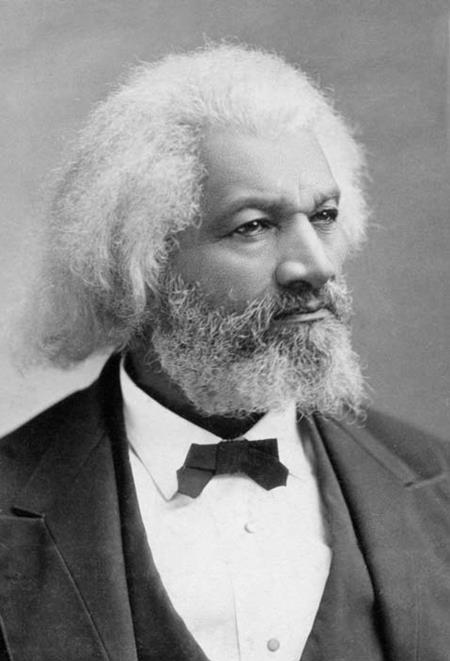

Tall with an iron countenance and thick mane of hair, Douglass began quite humbly with disclaimers about his “nerves” and his “limited powers of speech,” begging for his audience’s “indulgence.” Of course, the wonderful orator with a sonorous baritone voice was anything but inexperienced. From the masterful pauses, gestures and rhythms of his honed technique to his wit — including the ability to mimic Southern politicians — Douglass could hold a crowd’s attention for hours on end, often without notes and only his prodigious memory to guide him. As evidenced by the famous Lincoln-(Stephen) Douglas debates later that same decade, oratory was the primary form of entertainment and political debate at the time and, says Colaiaco, “no one more than Douglass understood the power of rhetoric to mold public opinion in a democracy.”

It wasn’t long before Douglass’ true aim became apparent. “Fellow citizens, pardon me, and allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence?”

And with the crowd growing more riveted and uneasy as it absorbed the former slave’s words, Douglass twisted the knife, including this famous passage:

What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: A day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless … your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery … a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.

Douglass, who also praised the nation’s founders “for the good they did, and the principles they contended for,” expressing hope that the “young” nation would someday overcome its injustices, provoked precisely the anger, shame and discussions he had intended — both inside the hall and across the country in the weeks and months that followed.

For Americans looking to celebrate this Fourth of July weekend with something meatier than a backyard hot dog, take a few minutes from the picnics and parades to read or listen to Frederick Douglass’ words, and reflect on how far we have come as a nation, and how much further still we must go.

You can read the full text of Douglass’ speech here, or watch James Earl Jones, another fine, baritone orator, read excerpts below.

++++++++++++

Sean Braswell is a Senior Writer at OZY. He has five degrees and writes about history, politics, film, sports, and anything in which he gets to use the word “futilitarian.”