The Plunder of

Africa

How Everybody

Holds the Continent Back

>via: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/review-essay/2015-06-16/plunder-africa

__________________________

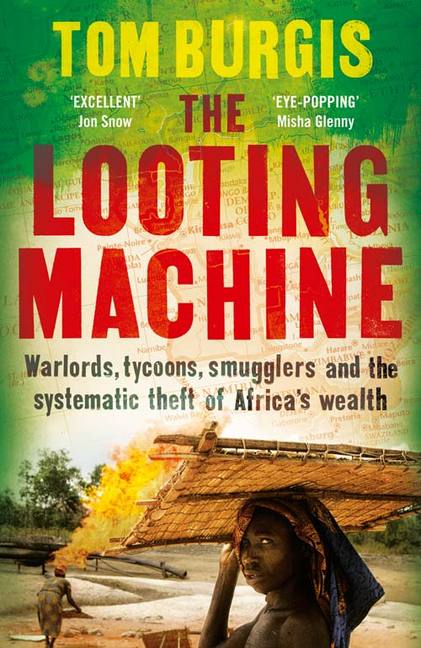

The Looting

Machine

by Tom Burgis

– reviewed by Desné Masie

Tom Burgis’ The Looting Machine is a rollercoaster read. Filled with vignettes on spooks, smugglers and kleptocratic warlords with suitcases of cash, it reads like a crime thriller, while at the same time being a well-researched, accessible account of the extractives industry; the privatisation of power in Africa and its impact on the continent’s people. This portrayal of the intersection of business and politics, and its potentially corrupting influence may also explain the paradox of rising GDP growth coupled with increasing inequality – a key problem in the era of ‘Africa Rising’.

Each chapter of The Looting Machine deals with a different country and a particular issue in its political economy, but some main unifying themes stick out. For example, the impact of the ‘resource curse’, hollowing out the economies of developing countries. Burgis also tackles the much-debated role of China in Africa, as globalisation atomises power to new sites of influence and capital. Additionally, he is concerned with the impact of financial secrecy, and potentially inequitable tax practices on developing economies; and how this facilitates rent-seeking.

This is all tied together by Burgis’ argument for the pervasiveness of the so-called ‘Queensway Group’, incorporated in Hong Kong, which is depicted throughout the book as a sort of global corporate mafia with the shadowy middleman Sam Pa as its kingpin. Crucial to Pa’s modus operandi on the continent, according to Burgis, is his leveraging of ‘guanxi’ (关系), the system of social networks and influential relationships that facilitate business and other dealings. The monetisation of such political relationships is also depicted by Burgis in the multi-million-dollar bankrolling of the Kabila dynasty by the businessman Dan Gertler in the Congo, the enrichment of South Africa’s politically-connected black oligarchs, the Futungo in Angola, and the involvement of Beny Steinmetz in Guinea.

Having been a financial journalist myself, I am amazed at how far Burgis has gone in untangling the web of corporate structures sometimes used in international financial chicanery. For example, at the Marange diamond fields in Zimbabwe, he assumes the bearing of a diamond trader in order to get through a checkpoint into a mining zone. And indeed, the book begins with a candid foreword about Burgis’ treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of some of the awful things he had seen on the continent – most notably a massacre in Jos. It is imagery like this, juxtaposed with private jets and gleaming corporate boardrooms from London to Luanda, that underscore the book’s insights.

Due to the continent’s egregious inequality, the rich in Africa can live in an insulated poverty-free bubble. In visiting the slums of Angola and the townships of Johannesburg, Burgis has therefore made a concerted effort to find the truth behind annual financial results and stock prices.

Financial journalism is usually one of the cushier parts of the profession, with meetings normally taking place in plush hotels and restaurants or corporate HQs. Working at a premier title, the average day generally consists of a reporter flitting from meeting to meeting with CEOs and their PR minders sprinkled with corporate gifts and briefings with the Finance Ministry and regulators. The capture of financial journalism can therefore be corrupting for all parties involved, and the importance of the support of the Financial Times newsroom for investigative work such as this, and its practice of picking up the bill for lunch, cannot be understated.

However, while it is undoubtedly important to expose corporate malfeasance and stamp it out, I do think that journalists also contribute to a particular narrative of sensationalist bad news. I would really like to see more stories and books about what is working, and could be done better in globalised supply chains, such as this, also in the FT, about the Dutch company Fairphone, which was incubated near London’s Silicon Roundabout in Bethnal Green.

Burgis begins his book with the balancing caveat that there are definitely some businesses which have a positive impact on Africa, and later he is at pains to point out that not all financiers or bankers are shady. However, The Looting Machine is by no means a glowing account of the role of business in Africa. An informant laments to Burgis that foreign business people think that in Africa anything goes, and that they therefore do things in Africa that they would not consider back at ‘home’.

Burgis obliged me by answering some questions on the role of business and international finance in economic and human development in Africa.

DM: It would seem that you are ambivalent about the altruism and outcomes of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), where initiatives such as “community development” and the Kimberley process have (unwittingly) contributed to, and incentivised conflict, malfeasance and money laundering amongst kingmakers and power-brokers. Have I understood correctly?

TB: Yes I think that’s broadly it. Also that CSR can be used to mask corporate abuses such as trade mispricing and tax evasion.

DM: What do you think could be done about financial secrecy and aggressive corporate tax avoidance? How can developing countries in particular fight for their interests in contracting?

TB: One option would be for governments to decline to do business with companies registered in tax havens.

DM: Mineral beneficiation seems to have worked well in Botswana … What do you think of new mining legislation in South Africa in this regard, and mining legislation such as the Zambian mining tax and the pros and cons of these for developing countries?

TB: Focussing on beneficiation makes a lot of sense. Why should that value accrue elsewhere? SA-made catalytic converters would be a success story. Protectionism is a dirty word but without tariffs how do you protect nascent domestic industries? On Zambia, the tax take has been so minimal in the past (circa 2-3 per cent) that no one could in good faith object to an increase, I would say. The difficulty is managing that added revenue to stop it causing havoc as resource rent often does.

DM: You say that the corporatisation of politics has replaced ideology, and the politicisation of corporate life through the accumulation of ‘guanxi’ is expressed through the monetisation of networks, parallel states and rent-seeking. What in your opinion can be done?

TB: The hardest question of all. These are transnational networks that float beyond the reach of national institutions that might call them to account – judiciaries, parliament etc. It’s part of the simultaneous globalisation and privatisation of power. No simple answer. But somehow the balance of power has to become more local again.

DM: Who is this book aimed at and what do you wish them to take away from it?

TB: A general, engaged reader. No prior expertise of Africa required. Thriller fans and politicos equally welcome! The idea is to prompt debate, not prescribe lots of (far-fetched) solutions.

DM: I am amazed at the personal toll and obvious risk to your life that came with this book, the quality of which makes the amount of work, the information you have accumulated and the quality of the research quite obvious … Why? What did you wish to achieve by writing this book?

TB: The point of journalism is to call power to account, and I hope the book does that in some small way. The personal toll you mention is real, but far smaller than that endured by many of the people I wrote about.

DM: I think it was really important to highlight the complicity of both westerners and Africans as regards the human and environmental cost of these issues. The insatiable need for cheaper and faster smart-phones has made us turn a blind eye to human rights abuses both in Africa and China. How could we encourage businesses, politicians and consumers to understand the long-range positive impact of sustainable business and addressing inequality meaningfully? Why do you think there is so much apathy about this? Is the problem too big to tackle, or is there no turning back as one of your protagonists says?

TB: It’s odd that western consumers insist on knowing the origin of their coffee but not of their copper. There’s been some progress on tagging minerals from eastern DRC, though that process also creates new trouble.

DM: You talk about China in Africa and have been criticised for comparing China’s rise in Africa to neo-imperialism – although in the book you do critique Western imperialism – what would you say to these critics? Do you wish to clarify your opinion on China’s role in Africa?

TB: Both true in different countries. There’s certainly a neo-colonial approach (as encapsulated by Sanusi) but it’s also understandable that China’s largesse is understandable compared with centuries of exploitation.

DM: I was astonished to read about the alleged pervasiveness of the business interests of Sam Pa via the Queensway group, and it is a theme that runs through most of the book. Is he the only such mega-player from China or are there are other corporations and groups of which you are aware of operating on the continent, and that you can talk about?

TB: There are lots of other middlemen but he looks like the biggest.

DM: Any closing thoughts on globalisation?

TB: Was the pope perhaps right – globalisation as a way to enslave nations?

Dr Desné Masie is a former Senior Editor for the Financial Mail and was the Corporate Relationship Manager for the Royal African Society. Her doctoral thesis evaluated the effects of news media in financial markets and on corporate reputation.

>via: http://africanarguments.org/2015/03/19/the-looting-machine-by-tom-burgis-reviewed-by-desne-masie/