BLACK MILLENNIALS

THE CURIOUS CASE

OF LUPE FIASCO

When rap mogul Jay Z called Lupe Fiasco “a breath of fresh air,” I couldn’t agree more. The year was 2006 when he released Lupe Fiasco’s Food and Liquor. The transition of hip hop as a lyrical haven to a pop culture fixture, was well underway. Gone were the days when stellar rap music was measured by lyrical content and impassioned delivery. Now, the “best” rap songs were weighted on catchy beats and concise hooks and choruses, so as to be repeated easily. Rap was no longer a labor of love, it was a corporate chop-shop.

Lupe entered the mainstream as hip hop was changing from a lyrical exercise to a constant headbanger. At the time, I was proud of Lupe. As hip hop crippled with every Yung Something, Lupe stood strong. His spirit, bold. His content, deep. His musical prowess laid unchallenged in a wave of one-liners. The album performed well and garnered him four Grammy nominations. He won one with “Daydreamin’,” which featured sexual songstress Jill Scott.

A year later, he followed up with Lupe Fiasco’s The Cool, an album I believe qualifies as one of the greatest hip hop masterpieces of all time. Riding the moderate wave of Food and Liquor, Lupe delivered a powerful single in “Superstar,” with Matthew Santos crooning throughout. His public profile was rising significantly. Rumors of Child Rebel Soldier, a rap super-group with the likes of Lupe, Kanye West, and Pharrell, caused reverberations of intersectional excitement.

But his public profile coincided with the rise of internet downloads and piracy. The music industry was slow to minimize, or at least, level the exponential growth of illegal downloading. Lupe, already an awkward placement within the hip-pop stratosphere, felt the blow back. The Cool performed well on the charts, but didn’t ultimately penetrate nor resonate with the masses. Full of heavy political content, the masses sidestepped the lyrical intricacy for even more easily-digestible club hits.

There was pressure on Lupe. From the label. From his fans. From within. He needed to make an album which adapted to the consumer of the time. Simple. Quick. Easy. He gave us Lasers (2011). As a Lupe fan, I was sourly disappointed. Quick and simple was not Lupe. Selling out was not Lupe. Lupe was an artistic revolutionary; I could depend on him to fight back against the cultural flavor of simplicity. But with Lasers, he abandoned his charge. Regardless, there were some gems, “Shining Down” being one.

Depending on the prism from which one looks, Lasers is either a success or failure. This album is the only of Lupe’s to debut at number 1 on the Billboard 200. However, sales rapidly fell in the following weeks as many exposed the album for what it was; a concession to the musical trend of the time. Andy Kellman of AllMusic said it best: “If there is one MC whose rhymes should not be dulled for the sake of chasing pop trends, it’s Lupe Fiasco.”

Lupe’s stock continued to fall when, one year later, he referred to President Obama as a “terrorist.” Already a maligned fixture within pop culture, Lupe infuriated many in the Black community with his seemingly glib statement. For me, I understood where he was coming from: scholars, experts, and commoners alike recognize that global terrorism is largely fueled by foreign policies cemented in white supremacist capitalism. Lupe weathered the storm, largely because such school of thought is credible.

However, there was little recovery or public relations mending that could fix the unnecessary follow up. In 2013, Lupe was kicked off stage during an inaugural party performance after, yet again, chastising the President for a half hour. The maxim “there’s a time and place for everything” was more than fitting.

The timing of his rhetoric were even more problematic considering he had released an album only a few months before. Released in September 2012, Food and Liquor II: The Great American Rap Album Pt. 1 was met with critical acclaim but didn’t have the commercial sales to match. The lead single “Around My Way (Freedom Ain’t Free)” was a remarkable return for the lyrical engineer, but received hardly any airplay.

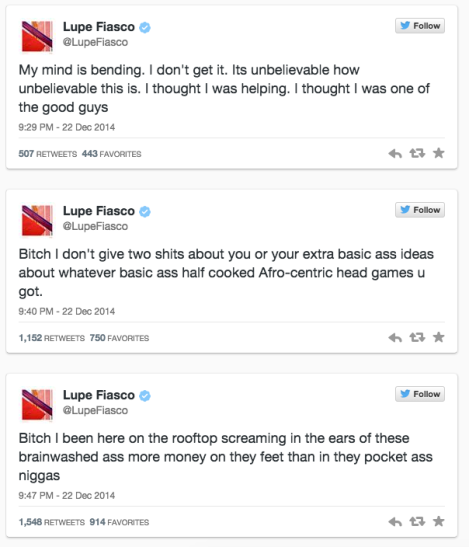

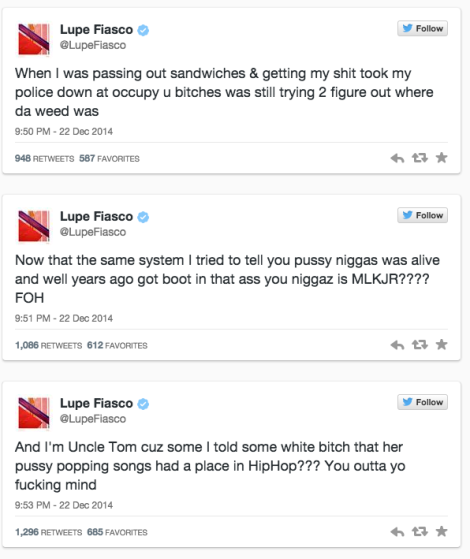

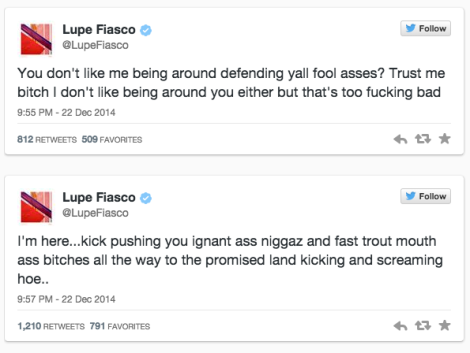

It was around this time when Lupe’s bitterness went public. However, his anger was less about legitimate Black rage, although his frenzied furor was embedded in built on it. Lupe was mad at his community, his Black community, for not embracing his craft in the same ways that we did Rick Ross and “rappers” of similar ilk. My friend perfectly summed it up as “horizontal hostility.” Lupe was no longer *publicly* lashing out systems or institutional racism…he was chastising and berating the victims of structural oppression, especially women. His Twitter page reads as a tragic onslaught of mockery. He regularly calls Black women “bitches” and other derogatory terms. His deep-seeded patriarchy took me by surprise, especially considering his musical history of promoting female empowerment.

The musical world is transforming, yet again. But unlike the first major transition in which Lupe found himself a novice, he is seasoned in the ways of shifting musical tastes and the cultural mores that define it. iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube are no longer dastardly thorns in a music executive’s side. Online platforms are more easily leveraged to equate to album sales.

The market no longer solely craves the trap music taste. The New School of Hip Hop, the real winners in the industry, are giving us social and political insight alongside exceptional production. J. Cole is a prime example of such. With no radio singles and little promotion, J. Cole gave us the wildly successful 2014 Forest Hill Drive.

And Lupe is largely responsible for the shift. He was the martyr, the guinea pig, the sacrificial lamb. He laid the corporate foundation for lyrical heavyweights Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole. Lupe was an industry sacrifice; he was the unique experiment who served to educate the archaic music industry that lyricism and anti-establishment business maneuvers, when coordinated correctly, are insanely marketable.

Simply put: Lupe was an artist before his time.

Lupe is still trudging along this new world of social online media. Recently, he found himself in the middle of the Azealia-AzaleaTwitter joust, with anger misdirected in almost every direction. Ironically, his series of tweets perfectly sums up his current mentality.

Despite his downward spiral, Lupe is keeping his head above water. His latest album Tetsuo and Youth is expected on January 20th, and many die-hard Lupe fans are looking forward to the magical prowess he regularly brings to our sonic palette. But as a public persona, as a human being caught and embittered by the stresses of celebrity, who knows what venture he’ll find himself next.

Underneath the egregious horizontal hostility, is a man who’s been used and tossed aside by corporate bureaucracy. He is hurt; feeling betrayed by the Black community because we, as a whole, didn’t uplift him in the manner he deems appropriate. And now, we are the receivers of his misplaced ire. Right before our eyes, we watched a spiritual revolutionary transform into a intransigent shell of his former self.

+++++++++++++++++++++

Arielle Newton, Editor-in-Chief. Get at me @arielle_newton. Get at us @BlkMillennials.

Arielle Newton, Editor-in-Chief. Get at me @arielle_newton. Get at us @BlkMillennials.

>via: http://blackmillennials.com/2015/01/08/the-curious-case-of-lupe-fiasco/