December 23, 2014

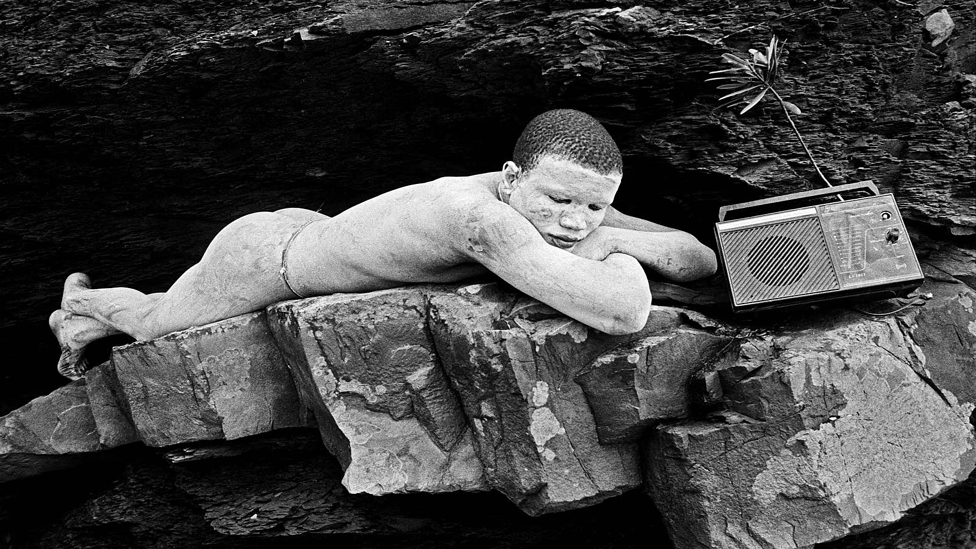

It’s a story of most young South Africans. We all move from the countryside to the city to better our lives and to find jobs. The idea was not to … I didn’t come to Johannesburg to work as a photographer but the idea really was to find a job for myself.

This is where – I used to stay here. After moving from Hillbrow, I stayed in this building with friends, Sipho and (indistinct). I studied photography when I was still at home then while I was working, searching for a job I saw, ‘Market Photo Workshop’, on a board and I went inside. I went back there and while I was sitting outside while the intermediate class was starting they were like, ‘Why are you sitting outside’, and I said, ‘But I don’t have money’, and they said, ‘Sit down here, we’re coming now’, and then they called me to a class and from then they gave me a bursary. I explained myself and my situation so I was given a bursary until my advance.

The one outside (is saying) ‘Women are not allowed inside. How did they get in?’ (calls answer to man).

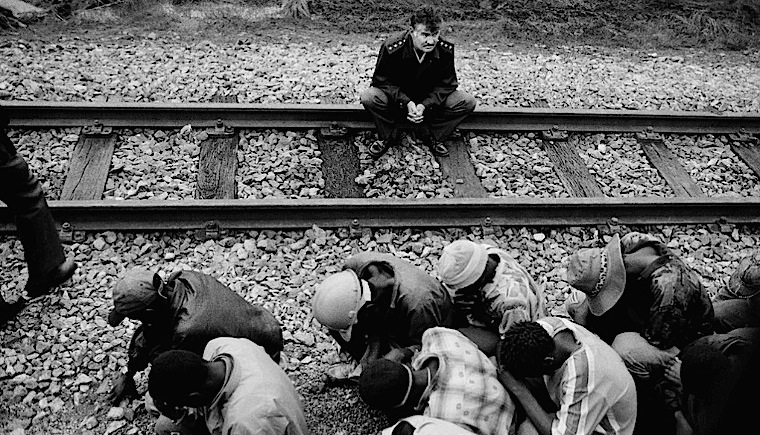

It used to be for immigrants coming into the city but now it’s a home of taxi drivers, security guards, people who are working in the factories and people who have moved to the city to find jobs.

So I started right at the end of 2006 to visit the hostel. That wasn’t really to make any photographs, I was just going there to visit and drink beer and come back home and sleep over. And slowly I started to come with a digital camera because I wanted to see how they react. And I saw the reaction: ‘Which newspaper are you from? No, We don’t want to be photographed’ and things. And then I came with the ‘point and shoot’. After I came with the Yashica 6’ by 6’- people started introducing themselves to me.

Photographs are powerful. Sometimes, it’s very important to understand the people. I don’t like the idea of just coming and ‘click’ and going. If you want to get that richness, that intimacy, you need to spend time and understand the people … understand exactly what they like, what they don’t like before even taking a camera and shooting.

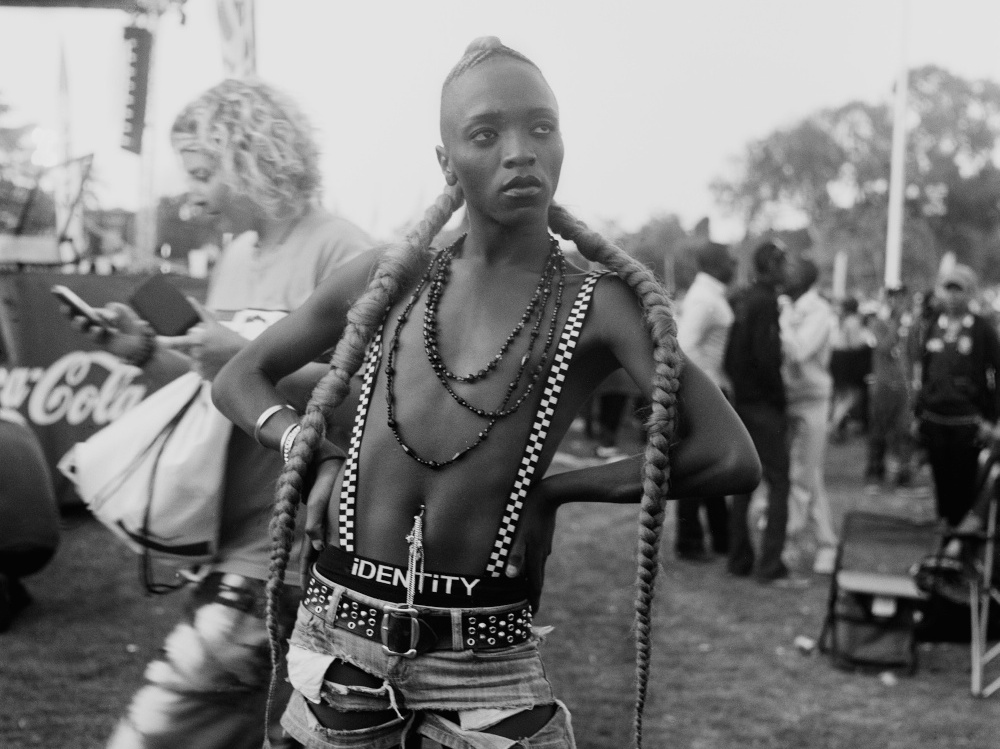

There are so many interesting things in a hostel besides everything. You find guys wearing skirts not because they are gay. I find it very interesting because nowadays we are very scared to hold hands and walk in the streets because of the stigma of being called a homosexual. I found the men were more open about that. They didn’t care. No one would say anything because he’s wearing a skirt. Those kind of things which, as men we are losing them now. Some other men don’t even want to be hugged. They’re saying, ‘No, no, no, don’t give me a hug.’ I felt like they were very free.

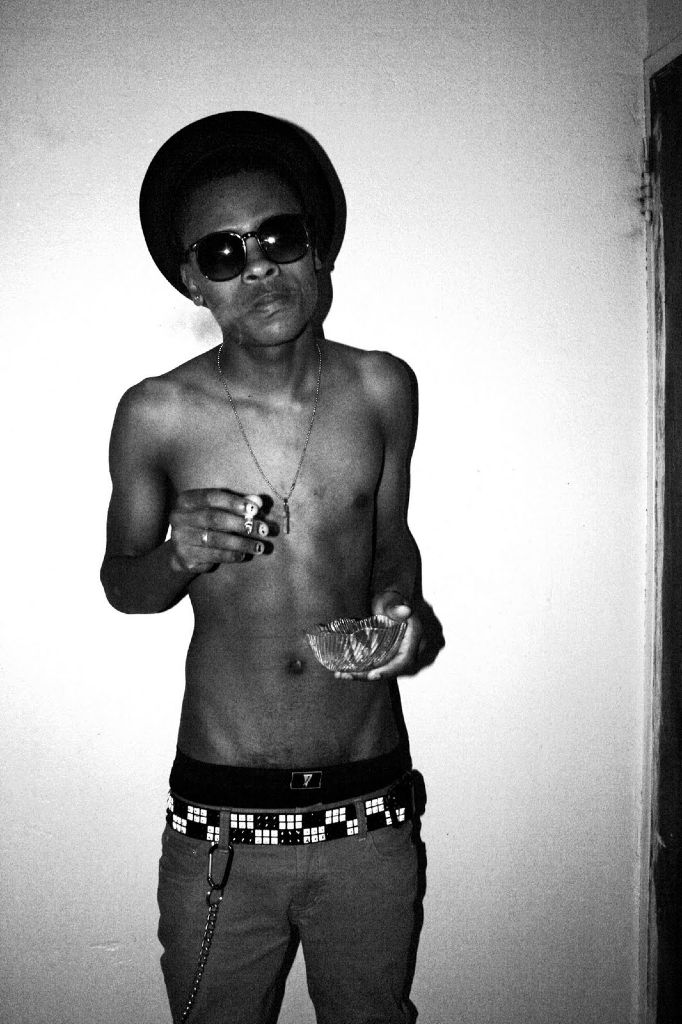

I started working on ‘Country Girls’ in 2003. I discovered this group of gay guys living in a small town in South Africa. What I found out that was interesting about them was that they were very united, as much as there was hate and whatever, they were together and fighting for who they are. When I was there I discovered that they don’t want to be called men. If you call them men, it’s like a big insult. So they want to be called women – sorry, girls. So I thought that ‘Country Girls’ would fit very good for the project.

Sipho has got a very interesting story because his father beats him up very strong because of his sexuality but what I like about him is the minute his father stops beating him up, he takes his high heels, puts them on and walks in the streets so, ‘Even if he beats me up,’ he says, ‘he can’t change who I am’.

My work is not about poverty really because I try all the time, even if it’s the space but I try to get people in their happy mood, in their daily life but in a very good presentation. I try to find beauty in a place where you think there’s no beauty, where you look at it and think there’s no beauty there. But all the time I try to find that thing that makes their life move on.

Transforming

South African

photography

Joburg’s Market Photo Workshop is partly responsible for the dynamism and breadth of contemporary South African photography today, and it is quickly becoming one of the best of its kind in the world. Jorrit Dijkstra interviewed its director, John Fleetwood

South Africa might be one of the most infrastructurally developed countries on the continent, but when it comes to photography there is still a lot to improve. Without proper training or representation, aspiring photographers are stuck. This is where The Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg plays its role, laying the foundation for those whose talent suggests they have what it takes to conquer the international photography scene.

“In 2014, photography from the African continent is a convoluted and complex matter”

It’s hard to imagine that world-renowned photographer David Goldblatt started the Market Photo Workshop in his hometown of Johannesburg already 25 years ago, back in 1989. Ever since, the training institution has played a major role in ensuring that, in their own words, “visual literacy reaches neglected and marginalized parts of South African society.” The workshop is now an established and well-respected place for national photographers to start their career. “Many of our alumni have changed and transformed the landscape of contemporary South African photography,” says director John Fleetwood, mentioning names like Zanele Muholi, Jodi Bieber and Sabelo Mlangeni. That is definitely something to be proud of. We asked John, who has been guiding both the educational and artistic framework of the workshop for over ten years, a couple more questions to get to know more about the Market Photo Workshop and photography in South Africa.

TIA: Can you tell us something about the history of the Market Photo Workshop?

JF: Our initial focus was on social documentary photography, providing them an entry into the media landscape. This was the core of the curriculum, because photography as a social and political practice was an important strategy in documenting the socio-political landscape of apartheid South Africa. Ever since we’ve adapted with time and we now offer formalized short and long courses in photography, educating learners in all technical and practical aspects of the medium. We’re not just a school anymore, but also a gallery (since 2005) and project space. Next to that we run multi-layered public and development programs. With this we create a viable and tangible transformation and development opportunities that engage with a greater community within society.

How much of your time goes on educating compared to exposing and representing photographers?

The Market Photo Workshop is actually really small and we have to work on one project at the time. Up until 2010 the majority of our operation was about training and focusing on the successful photographers we educated. Since then we’re really aimed at creating a bigger photographic community and [focused also] on other aspects of having a professional career within photography. One of the advantages of the workshop is that we’re dynamic and can shift our interests, which is necessary to stay ahead. The glitch of a gallery and international fame seem nice though, but our main aim will probably stay with education in the future. With forty per cent of people under 25 unemployed, you can imagine how important a good education is, especially for photographers.

What do you think of the status regarding photography in South Africa?

It’s a complicated spectrum that I have to break down. On the one hand we’re really blessed with the continued flow of talented photographers that pass through the workshop and are now established in the market. At the same time however, the government gives less and less funding to art and culture projects, and that affects us. We don’t have the same budget to support our students and are both struggling. How that’s going to develop in the future is exciting as well as scary.

And how does the international audience perceive this?

There is a strong interest in African photography from the international scene and South African artists are of course making use of that. There is a growing market in general, but mainly from abroad. This interest is not really seen within the country or even the continent. That’s a shame, because their talent should also be recognized by a local audience. Having said that, I see that this is even more the case in other African countries; in South Africa photography is at least seen as a real profession. Therefore we have a system that gives talent from other African countries a chance to partake in a course by administering a quota. We aim to have a quarter of each class be non-South Africans.

Earlier this year you were one of the jury members for the photography competition POPCAP. Do you do that more often and what is the value for your students?

I’m involved with a lot of photography awards in South Africa as well as internationally, either as jury member, nominator or curator. For me personally that’s very important to keep up with what is happening in photography around the world. I have to admit that I do look out for (African) photography and more specifically photographers from South Africa when involved, because I feel there is a real need to promote ‘my own’ photographers. Having said that, the African continent is very big and I cannot talk about countries I haven’t been or don’t know the scene. Yet I have met a lot of them and that makes it easier to understand and consider their work.

Having been in the (African) photography scene for so long, has it changed visibly over the years?

I think that in 2014, photography from the African continent is a convoluted and complex matter. Exposure does not equal acknowledgment or meaning and we are seriously struggling to explain to our audience what our photography is about. Young photographer, especially, don’t know what to actually show. If their subject is not within the realm of their audience, they easily miss out. This happens everywhere, but in my opinion especially in Africa. Part of the audience already has an opinion about what photography should look like when made by Africans and that causes a wrong pattern of expectations.

“Blackeneze”, 2001. Pigment inks on cotton rag paper. 69 x 54cm. Edition of 10. © Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko

Do you see something changing in the way African photographers portray their subjects, or in the subjects chosen, that can be linked to the continent’s rising economy?

“Part of the audience already has an opinion about what photography should look like when made by Africans”

On the one hand yes, because there are definitely photographers shifting from documentary to art photography because they have the means to do so. On the other though, most of them still think it’s very interesting to photograph the poor, the working class and the struggling. Interestingly the middle class has also come up as a subject for projects, mainly because there is so much diversity in this group of people. A growing middle class doesn’t mean the photographer is actually a benefactor is this, which resonates in the subjects of my students especially. Perhaps there is an opening there, but that needs to be explored further.

Can you talk about the quest to reclaim “over 100 years of photographic misrepresentation” as Dr. James Michira puts it?

Photography is the perfect medium to record what’s happening around you, not what is going on somewhere else. With documentary photography coming up on the African continent and many of our students being involved in it, they are writing their own history. It’s about documenting and authoring at the same time, and a complete picture encompasses both. In that sense the documentary photographers from the continent now are completely different than the ones from abroad in the last century. Next to that their intensions also differ, of course.

Photography is a self-narrative and starts within your own world. You have to position yourself, and African photographers definitely chose the right subjects in modern day society to show a new view to the outside world. They are the best interpreters to what they experience every day themselves.

+++++++++++++++++++++

Jorrit R Dijkstra is an arts & culture journalist, specialized in photography. Born in the Netherlands but living in Australia, he developed a passion for the continent of Africa on his very first visit. Next to his freelance writing he’s also the senior editor of Silvershotz, an interactive contemporary photography experience.

>via: http://thisisafrica.me/lifestyle/market-photo-workshop-transforming-south-african-photography/