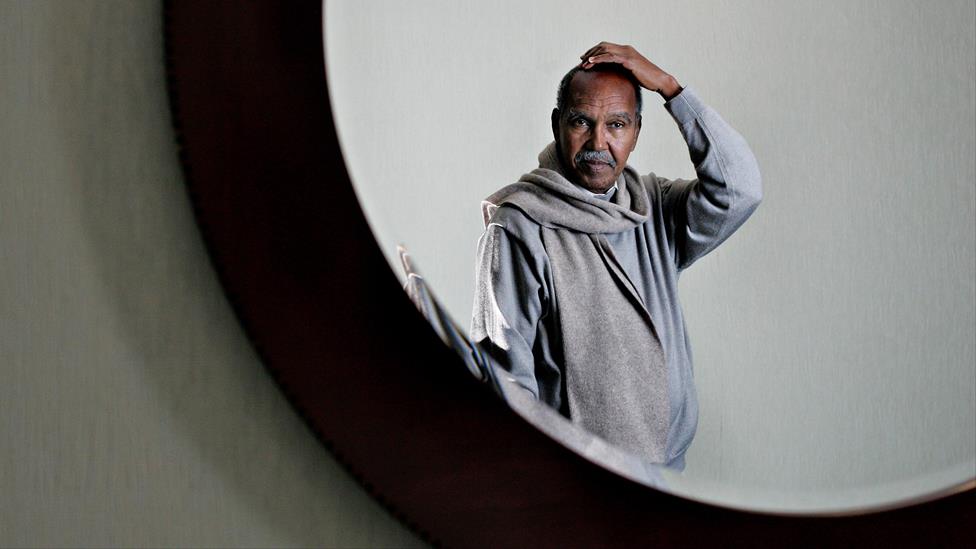

Nuruddin Farah, 68, hasn’t won the Nobel Prize in literature. Yet.

But he still has time, and his latest novel, Hiding in Plain Sight — out Thursday — could be one more sign that he ought to be discussed.

Somali-born, Ethiopian and Indian-educated, and a former resident of Germany, the United States, Sudan, Italy, Nigeria — Farah is nothing if not global. And yet, his work is also obsessed with problems that are particular to a certain region of the world — in this case, his motherland. Hiding in Plain Sight’s story follows Aar, a United Nations logistics officer who (like Farah did in the late ’90s) returns to Somalia after many years. Upon his return, he receives death threats from the al-Shabab terrorist organization. An attack soon erupts (no spoiler; it happens quickly). It’s a story that’s far too real: Farah notes, almost casually in the acknowledgments, that his sister Basra Farah Hassan was killed by a Taliban bombing in Afghanistan.

It’s all the more haunting, then, that the story follows Aar’s younger sister Bella, a photographer living in Rome. She and Aar’s estranged wife, Valerie, are put into conflict over the fates of Bella’s niece and nephew. Over the course of the book, the ways in which all of these characters interact allow Farah to raise questions of national identities, sexuality and aesthetics.

As I spoke with Farah over the phone, his dedication to human rights and his love of books were both themes that he returned to again and again. We discussed the roots and themes of Hiding in Plain Sight, as well as his fondness for working in trilogies, this particular novel’s invocation of certain books and the way art can illuminate social issues across the world.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

OZY:

Where did the initial idea come from?

Nuruddin Farah:

I’m obsessed, as you may know, with a few areas of life. One of them is what makes a person tick: What are our identities? Who are we, really? Are we the people we are, born into the country in which we are born and are brought up, or are we larger than the countries in which we were born and in which we were brought up? These are the ideas that have always come to me. And the other thing that, obviously, is very, very important for me is human rights. What matters to people? What choices can they make where they are safe from harm, safe from terrorism, and so on and so forth? These are the things that kept me going and that have always kept me going, right from when I started writing my first novel.

OZY:

Bella is a photographer in the story — how did you think about her art?

NF:

Her project — the one that she was going to work on, just before her brother is murdered — is one that would take in the conflict that is Somalia into account, in a photographic image of that in various parts of the world, because Somalis have now joined the world’s diaspora. Those are some of the things that have also interested me: to record all of these things, register the sorrows and the joys of finding a home elsewhere, and living in it.

OZY:

Let’s talk about sex. It’s a big deal in the book.

NF:

In truth, we in Africa, and especially in the Islamic world, are sex-obsessed. We’re obsessed with sex, but we avoid having a dialogue about it, both in Africa as well in the Middle East, in the Arab world, in the Islamic world. My interest is to start the dialogue — the dialogue that goes on between choices. How much of a choice does one have to admit to being homosexual in Africa or in the Middle East? My interest in the human rights of the individual started with my first novel, From a Crooked Rib, in which a young nomad Somali woman is being bought and sold. That’s the way we deal with it, in the tradition, and so the struggle still continues.

And I’m saying, inasmuch as it is right for democracy to take shape in Africa and the Middle East, democracy is that package that can’t be cherry-picked. You don’t say, “I want this and I don’t want this.” “We should insist on elections, but we won’t allow people to express themselves sexually in their own way.” Recently, I saw in the Ugandan and Kenyan newspapers about President Museveni of Uganda, who was harangued — there was a demonstration against his presence in the U.S. Hotels in Texas would refuse him admission; they wouldn’t want him to stay in the hotel. Some of these countries are obsessed in determining. … They say that homosexuality is un-African. My argument is, homosexuality is a human self-expression, and it is in Africa as it is in the Middle East, in Saudi Arabia, in Morocco, everywhere else. And yet people are in continuous denial. …

That’s how it all started, in fact. It’s the usual thing: It’ll be controversial, and then someone will say, “Oh, Nuruddin Farah — he lives somewhere else.” I’m saying that, as a young man, I knew homosexuals in the village and town where I grew up. But people would deny that. They would say, “It’s un-African.” And I’m saying, no, it is human. To be gay is human.

OZY:

A lot of your work falls into trilogies. Is the next novel you’re working on a thematic follow-up to this one?

NF:

It is very possible, but I may take one paragraph from this novel and work it into an entire novel. The characters may be new, but the characters will share a great deal of similarities with the characters in this novel. It may not necessarily revolve around sexuality. It may take us to another theme which is related to this. Religion is one; quite often, people quote the Quran or the Bible or the Bhagavad Gita, they have a religious side. The new novel may contain a lot of that — looking at life through a theological point of view. It may. As I said, I haven’t finished the entire novel. I’m working on it.

OZY:

What books do you admire? Did they influence this book at all?

NF:

For much of the time, I live by myself amongst books. Books are my friends, my companions. As I said to you, the characters sit at my table and have dinner with me when I am by myself, and sometimes even in company. When one writes one’s first novel, one can actually be truthful, and one may write as much as one knows about the life one is writing about. But the more books you write, the more you start a dialogue with other writers — other writers from the past, other writers from the present, one’s own friends’ books, books one didn’t like. This continuous dialogue takes me to other books. Inasmuch as it is wonderful to meet people, books are a lot more interesting than people.

+++++++++++++++++

>via: http://www.ozy.com/pov/sitting-down-with-a-novelist-scarred-by-the-taliban/36644