January 31, 2014

Printed in Africa

By Pooja Bhatia

WHY YOU SHOULD CARE

Here’s where to find a good book these days, along with some cutting-edge narrative and exquisite prose: Africa.

What a sad decade for the book business in the West. Publishers have consolidated, advances have shrunk and the hands of the sad old literary guard are sore from wringing.

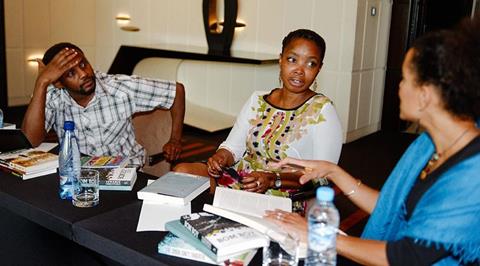

It’s a different story in Nairobi. And in Lagos, Abuja, Johannesburg, and even Harare. Over the past decade, these cities have become epicenters of a literary renaissance with truly pan-African potential. There are prestige publishers, big-money prizes and literary festivals galore.

The stories have shifted, too. Nowadays, there’s little angsting about national identity in a post-colonial context or, for that matter, over catastrophe and want. Instead, a bevy of young Africans are shaping the future of fiction, reportage and critique on their continent, and perhaps well beyond.

“It’s beyond an evolution — it’s a revolution,” says Nigerian-American Ikhide Ikheloa, a critic and prominent observer of the scene.

It may have begun in 2003, when Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s first novel, Purple Hibiscus, was published — and not just by an American publisher but by a Nigerian one, too. By now, Adichie is the still-young doyenne of the contemporary African lit scene. Her recent novel, Americanah, found a perch on the New York Times list of top 10 novels of 2013 — just weeks before Beyoncé sampled one of Adichie’s TED talks on her new album.

Or maybe the renaissance began with Granta’s publication, in 2005, of “How to Write About Africa,” an essay that skewered Western tropes:

In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions. Africa is big: fifty-four countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book.

Perhaps it had already begun in 2003, when the Kenyan author of that essay, Binyavanga Wainaina, helped to found Kwani Trust, a Nairobi-based literary house and publisher. Or in 2002, when Cameroonian-Capetown transplant Ntone Edjabe printed 1,000 copies of a new journal called Chimurenga. It has since succeeded in its aim to “get Africans to write about Africa as they saw it,” instead of following the lead of Western papers.

Such seeds have yielded a fertile literary landscape. Strong evidence comes in the current mania for book prizes across the continent. For years, the British Caine Prize dominated the arena, and not without some harsh criticism: “Ah, the tyranny of Mzungu prizes!”

Ah, the tyranny of Mzungu prizes!

But the years since have seen more African-led prizes.The first Kwani Manuscript prize for unpublished novelists was awarded in 2013. New this year: The Etisalat Prize for first-time novelists, sponsored by a mobile phone company and accompanied by a $25,000 purse, and the Africa39 prize for fiction writers under 40.

Homegrown publishing is a crucial ingredient. Adichie’s Nigerian publisher is a former banker named Muhtar Bakare, who believed that, contrary to the then-conventional wisdom, Nigerians would read — if only they had access to affordable literature. He was proved right, authors say.

But while Africa-based publishers such as Farafina, Kwani and Cassava Republic have helped make books more accessible and affordable across the continent, it is still difficult for, say, a Nigerian writer to be read in Kenya without being published by a London- or New York-based house, Edjaba said recently.

That’s one reason that Etisalat, the mobile company, is using its literary prize to support local publishing. It insists that the books of shortlisted authors be published in Africa as well as abroad. The idea is to contribute to Africa’s book infrastructure, says Ebi Atawodi, a Nigerian who led the prize’s design. ”As a writer, you’re just not going to go to a publisher and get the same benefits you’ll get in the western world,” she says. “They don’t have that kind of funding, distributions channels or basic infrastructure.”

“The Internet has at least broken up the West’s monopoly on publishing.”

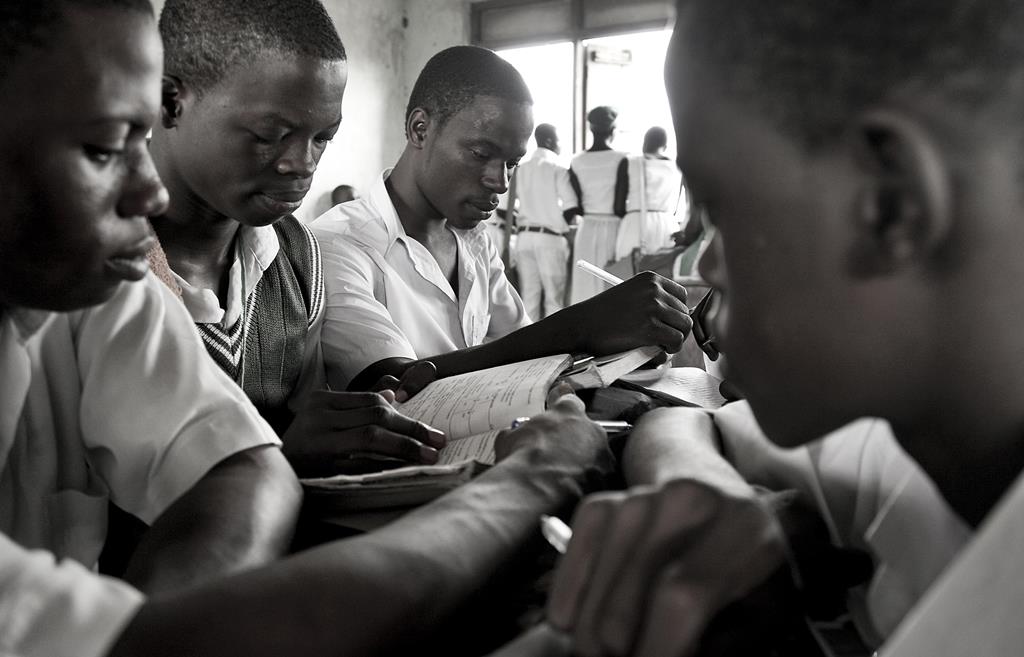

Until then, argues Ikheloa, the Internet has become “the number-one publisher of choice of Africans today.” And while Facebook posts and blog fodder might not come with a contract, the Internet has at least broken up the West’s monopoly on publishing. “We once had to go through gatekeepers, and they decided what stories to tell,” he says.

As the names of the publishers have changed, there has been a refusal to abide the usual story about Africa — war, poverty, dirt, hunger — and an insistence on diversity of narratives, themes and styles.

That idea was powerfully articulated by Adichie in her 2009 TED talk, The Danger of a Single Story, in which she spoke against the tradition of writing about “Sub-Saharan Africa as a place of negatives, of difference, of darkness.” The talk has been viewed more than 6 million times on TED. Nope, it’s not the one Beyoncé sampled.

Wainaina, who wrote the Granta satire, is another lodestar of the movement. He is a 43-year-old Kenyan who is to contemporary African literature what Salman Rushdie was to post-colonial literature back in the 1990s: a leader, advocate and omnipresence on the literary scene. He’s fierce, too. When, last month Nigeria outlawed same-sex relationships, Wainaina released a “lost chapter” of his acclaimed 2012 memoir that announced that he is gay.

Perhaps it was a stretch for his wide African readership. Or perhaps not: If the continent’s flourishing literary scene is any indication, they can handle that story, too.

>via: http://www.ozy.com/fast-forward/printed-in-africa/5972.article#.UuwbiJ0FRHw.twitter