America’s Civil War:

Louisiana Native Guards

By Robert P. Broadwater

Originally published by America’s Civil War magazine. Published Online: June 12, 2006

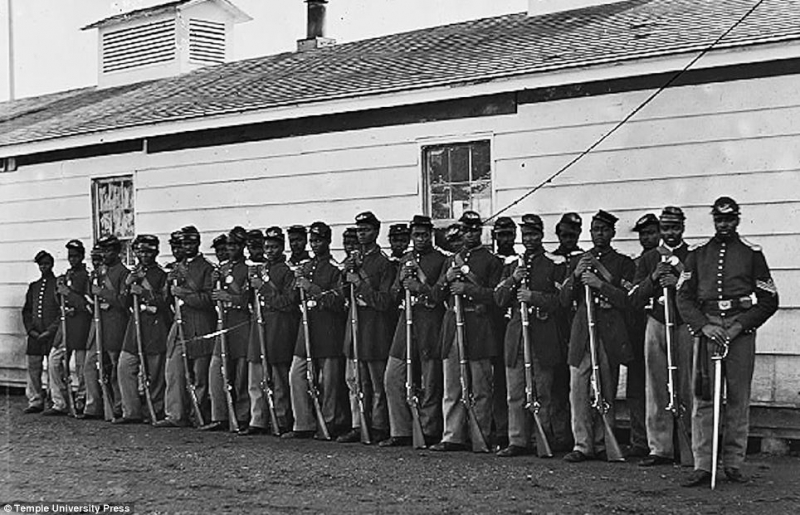

In general histories of the war, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry is usually presented as being the first African-American regiment in the Union Army to experience the trial of combat. In fact, the 54th Massachusetts’ assault on Battery Wagner took place almost two months after the Louisiana Native Guards had stormed a similar Confederate fortification at Port Hudson, Louisiana. They were the first officially mustered black regiment to fight for the Union, as well as the only unit in the Union Army to have black officers as well as white. Owing to the fact that they were far from the spotlight of media attention, their accomplishments were never fully recognized during the war.

The men of the Native Guards came from the New Orleans region. Most were free men of mixed-race bloodlines whose families had been given their freedom by the Federal government when New Orleans became an American possession through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

When the Civil War broke out, a number of the prominent free blacks of New Orleans met to discuss their course of action, and decided that they should support the new Confederate government and volunteer for military service. At first, Confederate authorities lauded their offer, and their patriotism was praised in local newspapers. On March 2, 1861, a month before the firing on Fort Sumter, theShreveport Daily News ran a story about ‘a very large meeting of the free colored men of New Orleans’ taking measures ‘to form a military organization, and tendering their services to the Governor of Louisiana.’

Praise was one thing; acceptance was quite another. Confederate leaders who had initially welcomed the prospect of black troops changed their stance in light of the growing influence of the abolitionists over the Federal government. In defending the propriety of slavery, Southern officials pointed to their long-standing argument that blacks were inferior to whites. Enrolling black troops on the same level as whites would tend to refute that argument to all the world, and the Confederacy opted to deny the Louisiana Native Guards the privilege of fighting for their new country.

A combined U.S. Army and Navy expedition accepted the surrender of New Orleans on April 26, 1862. But the capture of the city and the sealing off of the mouth of the Mississippi was just the beginning for the Federal army of occupation. The Union force, under the command of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler, needed reinforcements. A Massachussetts politician with abolitionist leanings, Butler knew that the resources of the Federal government were stretched, and forwarded a request to Washington for permission to raise regiments of local black men.

It was not the first time the idea had been proposed. Black troops had been raised by the Union from among freed slaves in the Port Royal, S.C., area after it was occupied by Federal troops, but that experiment had met with less than desirable results. The ex-slaves were badly treated, did not get paid and received little or no military training. Butler’s experiment would be different. Washington did not officially respond to the request, so Butler decided to proceed with the recruitment on his own.

He approached several of the prominent black men of New Orleans to learn their feelings about joining the Union Army. The men were the very same individuals who had offered their services to the Confederacy only a year before, receiving a humiliating snub in the process. They were still willing to fight, and they desired to show the world that they were the equals of any soldiers. The Louisiana Native Guards would indeed enlist in Ben Butler’s army.

On August 22, 1862, General Butler issued a general order authorizing the enrollment of black troops. The blacks of New Orleans responded with enthusiasm. Within two weeks he had enlisted more than 1,000 men and could form his first regiment. Orders stipulated that only free blacks were to be enrolled in the regiment, but the recruiting officers were extremely lax in enforcing this rule, allowing many runaway slaves to be entered on the rolls with no questions asked.

On September 27, 1862, the 1st Regiment, Louisiana Native Guards, officially became the first black regiment in the Union Army. The 1st South Carolina held the distinction of being the first black regiment to be organized, but it had never been officially mustered into the army.

The astounding response to Butler’s call continued. Within a few short months, enough black men from the area had volunteered to form four full regiments, thus augmenting Butler’s force by more than 4,000 men and helping to solve his shortage of manpower.

Many of the prominent black citizens of New Orleans had been appointed officers in the regiments, and they were itching to disprove the slanders that the Confederacy had used to keep them out of the army. One such example was Captain Andr Cailloux, of Company E. Cailloux was an esteemed and wealthy resident of New Orleans who liked to boast that he was ‘the blackest man in America.’ He had been formally educated in France, including instruction in the military arts. The captain was a born leader and presented a striking martial presence while drilling his troops, issuing orders in both English and French.

White officers with Butler’s army were rapidly won over to the idea of serving with blacks. It was generally noted that the blacks took to soldiering more readily than their white counterparts, and that they were easier to train and discipline. One white officer serving with the Native Guards sent a letter home that expressed his admiration: ‘You would be surprised at the progress the blacks make in drill and in all the duties of soldiers. I find them better deposed [sic] to learn, and more orderly and cleanly, both in their persons and quarters, than whites. Their fighting qualities have not yet been tested on a large scale, but I am satisfied that, knowing as they do that they will receive no quarter at the hands of the Rebels, they will fight to the death.’

Though they were proving themselves model soldiers in camp, the members of the Native Guards were denied the chance to prove themselves on the field of battle. Instead, they found themselves relegated to performing manual labor on defensive fortifications or guarding those same fortifications once they were completed. For the moment, whites were still considered the exclusive combat element of Butler’s army, and the Louisiana Native Guards would have to bide their time.

In May 1863, Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant were trying to wrest the stronghold of Vicksburg, Miss., from the Confederacy. Major General Nathaniel P. Banks was ordered to coordinate his efforts so as to assist Grant and keep potential reinforcements from being sent to Vicksburg. Banks decided the best way to do that would be to assault Port Hudson, a Confederate stronghold located 30 miles north of Baton Rouge, on the east bank of the Mississippi River. The Louisiana Native Guards were by then under Banks’ command, and he fully intended to use them in his coming offfensive.

Just before the operations against Port Hudson began, the Louisiana Native Guards were presented with their regimental banner. When Colonel Justin Hodge handed the flag to Color Sgt. Anselmas Plancianois, he cautioned him that he was to protect, even die for, the flag but never surrender it. Plancianois responded, ‘Colonel, I will bring these colors to you in honor or report to God the reason why.’ His words were met with wild cheering from the ranks. The men finally had a flag of their own, and they were about to follow it into battle.

Port Hudson was a formidable stronghold. It crowned an 80-foot-high bluff along a bend in the Mississippi and was virtually unassailable from the river. The only possible way to attack it was by land, storming the defenses from the rear, but the Confederates had taken every precaution to guard against that eventuality. A line of abatis, felled trees with the branches sharpened, ran the entire length of the perimeter. Behind this were rifle pits and outworks. Finally, there was the main earthwork fortification, with 20-foot-thick parapets, protected by a water-filled ditch 8 feet wide and 15 feet deep. All the fortifications had been constructed using slave labor. Behind the works, the Confederates had mounted 20 siege guns and 31 pieces of field artillery. Though confirmed totals are not available, it is known that the Confederate garrison numbered more than 6,000 men. Dislodging them from such a strong position would have been a difficult undertaking for seasoned troops. It would seem far too much to ask of untried soldiers, but the Native Guards were eager for the opportunity.

Union artillery shattered the early morning calm on May 27, 1863, as the fort came under a heavy cannonading, intended to soften its defenses before the infantry was sent in. For four hours, Union guns hammered the fort.

The Native Guards, 1,080 strong, had been placed on the extreme right of the Union line. At 10 a.m., a bugle call signaled the attack, and the Guards surged forward with a yell. Between them and the works lay one-half mile of ground broken by gullies and strewn with branches, but the Guards advanced on the run. As they neared the fort, they were met by blasts of canister, fired almost into their faces from the works to their front. Artillery also fired into both flanks, and the carnage was terrific. Yet the Guards still pushed forward, unaware that something had gone wrong in the Union attack plan, and that they alone were taking on the fort’s garrison, a force six times their number.

Captain Cailloux urged Company E to keep pushing forward. As the color company for the regiment, his men drew unusually heavy fire from the Confederates, and a bullet shattered Cailloux’s left arm. He refused to leave the field and continued urging his men onward till they reached the edge of the flooded ditch. ‘Follow me!’ he shouted just before being hit by a shell that took his life.

With their commander dead, the troops of the color company halted momentarily at the ditch, and the Confederate defenders raked them with musket fire at point-blank range. To attempt a moat crossing in the midst of such galling fire seemed suicidal, so the men fell back to re-form for another attack.

Once again they charged the works, reaching a point 50 yards from the enemy guns, but the result was the same. By now, the Guards’ right wing was the only Union force engaging the fort. Unsupported and facing the entire weight of the Confederate defenses, they continued to press forward in a futile assault.

A number of soldiers from E and G companies jumped into the flooded ditch and tried to reach the opposite bank, but they were all shot down by the fort’s defenders. A white Union officer who witnessed the charge said, ‘they made several efforts to swim and cross it (the ditch), preparatory to an assault on the enemy’s works, and this, too, in fair view of the enemy, and at short musket range.’

The courage of the Guards was inspiring. Doctors in the field hospital reported that a number of black soldiers who had been wounded in the first assault left the hospital, with or without treatment, to rejoin their comrades for the second attack. Dr. J.T. Paine recorded that he had’seen all kinds of soldiers, yet I have never seen any who, for courage and unflinching bravery, surpass our colored.’

But courage alone could not overcome the extreme odds the Native Guards were facing. Rebel muskets and artillery were too much for them, and the ever-mounting casualties they were suffering were beginning to take the fight out of the men. Once again, they were forced to fall back, but not before several efforts were made to recover Captain Cailloux’s body, all ending in failure.

Incredibly, the Union high command still seemed to believe that the Native Guards could do the impossible. The Guards re-formed, dressed their lines and started forward at the double quick for the third time. They were met with the same galling fire that had doomed the two previous assaults, but still they rushed onward. Color Sergeant Plancianois had advanced the regiment’s colors to the enemy works when he was struck in the head by a 6-pounder shell. In all, six color-bearers were killed trying to advance the flag before the Guards were ordered to withdraw. With deliberation, they re-formed their ranks and marched off the field, as if on parade.

Of the 1,080 Guards who took part in the battle, 37 were killed, 155 wounded and 116 captured. Their conduct had made converts of most of the doubters in Banks’ army and proved that black troops could play a pivotal role in suppressing the rebellion. Their courage helped to pave the way for the more than 180,000 black troops who would don the blue and fight for the Union Army.

Captain Cailloux’s remains were not recovered until Port Hudson fell on July 8, at which time they were sent home to New Orleans for burial. His funeral was attended by both blacks and whites. Cailloux may have boasted that he was the blackest man in America, but heroism knows no color line.

This article was written by Robert P. Broadwater and originally appeared in the March 2004 issue ofAmerica’s Civil War.

>via: http://www.historynet.com/americas-civil-war-louisiana-native-guards.htm

__________________________

Louisiana ‘Native Guards’

fight well for Union

By D. Terry Jones

Special to The Journal

When the Lincoln administration authorized the enlistment of African Americans into the Union army in 1862, the 1st Regiment of Louisiana Native Guards was the first unit to be organized. The army, however, did not believe African Americans would be dependable in combat so it restricted the new recruits to performing menial tasks as a way to free up white soldiers to do the fighting. This policy infuriated the Native Guards because they wanted to face the Rebels in battle. They understood that fighting was the only way to prove their worth as soldiers and to bolster their claim for equal rights when the war was over.

The Native Guards got their chance in May 1863 when General Nathaniel P. Banks surrounded the Confederate garrison defending Port Hudson, Louisiana. Port Hudson and Vicksburg, Mississippi, were the last two Rebel strongholds on the Mississippi River, and President Lincoln was eager to reduce them in order to split the Confederacy in two and reopen the river to Northern trade.

Among Banks’ 30,000 men were the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards. The general needed every man he could muster for an attack on May 27 so he decided to give the Native Guards a chance to prove themselves in combat. William Dwight, Jr., a thirty-one-year-old Massachusetts general, commanded the portion of the battlefield that included the Native Guards. Dwight wrote that he believed Banks had decided to use the black soldiers in order “to test the negro question. . . . The negro will have the fate of his race on his conduct. I shall compromise nothing in making this attack for I regard it as an experiment.”

Incredibly, Dwight’s “experiment” did not include scouting out the position the Native Guards were to attack or even studying maps of the area. As it turned out, Louisiana’s black Union soldiers were being sent into a tangled maze of felled trees, thick brush, and irregular ground which was, perhaps, the strongest part of the Confederate defenses. General Dwight remained in the rear drinking throughout the entire fight.

At about 10:00 a.m., the Native Guards moved forward across the six hundred yards of ground that separated them from the enemy. A third of the way across, Confederate artillery opened up with what was described as “shot and shells, and pieces of railroad iron twelve to eighteen inches long.” One shell took off the head of the 1st Regiment’s color bearer and scattered his brains on the men near him. Despite the horror, two soldiers stepped forward and vied for the honor to carry the flag. Captain André Cailloux, one of the few black officers in the Union army, had his left arm shattered above the elbow, but he continued to lead his company forward until another bullet killed him instantly. When Cailloux’s men saw him go down, they fired one volley and retreated in confusion. The Confederates kept up a steady fire, and one later wrote, “We moad them down, and made them disperse, leaving there dead and wounded on the field to stink.”

Out of the approximately 1,000 Native Guards who participated in the attack, 36 were killed and 133 were wounded. The 60 Confederate defenders facing them did not lose a single man. For the entire day, Banks lost about 2,000 men to the Confederates’ 500 casualties.

Northern newspapers and magazines wrote extensively about the black soldiers’ bravery at Port Hudson, although they greatly exaggerated their accomplishments. A Harper’s Weekly illustration showed the Native Guards mounting the Rebel breastworks and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. In fact, the main attack lasted about fifteen minutes and none of the black soldiers got anywhere near the Confederate position. The most significant contribution the Native Guards made at Port Hudson was proving that African Americans could fight as well as white soldiers. In the days following the doomed attack, many officers and men made note of the Native Guards’ bravery and heavy losses. General Banks told his wife, “They fought splendidly!” and an enlisted man proclaimed, “All agree that none fought more boldly than the ‘native guards’.”

The Louisiana Native Guards were the first African American soldiers to see combat in a significant Civil War battle. Largely because of their service at Port Hudson, Union officers began recruiting more and more African Americans into the army and sending them into combat. By war’s end 180,000 blacks served the Union, with Louisiana providing more soldiers than any other state.

++++++++++++++++++++++

Dr. Terry L. Jones is a professor of history at the University of Louisiana at Monroe and has published six books on the American Civil War.

>via: http://www.thepineywoods.com/CivilWarMay13.htm

__________________________

Monday May 27th, 2013 9:37 AM

150th Anniversary of US Colored Troops officially fighting for a greater measure of freedom for people of African ancestry remains an open secret. Sadly the ongoing and escalating “Racism in our California Public School System” is best seen in the omission of the contributions of our service members of African ancestry to end “Slavery in California” and throughout the United States.

“The first major engagement in which black soldiers participated was an assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana, in late May 1863.

Control of the Mississippi River had long been a goal of the Union Army, and by the spring of 1863 it had secured the river’s entire course, except for Confederate bastions at Vicksburg, Mississippi and Port Hudson, Louisiana.

To cut off the Confederates in the Trans-Mississippi West and provide Midwestern farmers with a water route for the shipment of their crops, the War Department determined that a command under Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant was to capture Vicksburg, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, head of the Department of the Gulf, was to seize Port Hudson.

For months the Confederates had been fortifying Port Hudson, particularly to the south and west, taking full advantage of the choppy terrain to erect an ominous defensive position. The occupation force consisted of some six thousand Confederates under the command of Maj. Gen. Franklin Garner, a gritty officer and talented engineer who hailed originally from New York.

In late May portions of Banks’s Nineteenth Corps converged on the area around Port Hudson, and after some intense fighting the Federals took a horseshoe-shaped position around the Port Hudson garrison, with flanks nestled near the river. Among Banks’s besiegers, filling in at the northern edge of the Union line and closest to the Mississippi river, were the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, later the 73rd and 75th U. S. Colored infantry, a little over one thousand black soldiers in number.

The 3rd Louisiana Native Guards consisted of former slaves who had white officers. Originally, the regiment had black line officers, but efforts by Banks to purge the Louisiana native Guards of all black officers had already driven them from the service, regardless of qualifications or competence.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guards, though, were free {non-enslaved} blacks, with black captains and lieutenants who for the time being were unwilling to buckle under Banks’s pressure. According to its white colonel, the regiment had some of the best blood of Louisiana, the offspring of sundry white politicians, as well as numerous prominent and wealthy {non-enslaved} free blacks from New Orleans.

The next morning, when they assembled in position to begin their advance, no one in the Federal Army had examined the terrain. Several days earlier, as Banks’s forces approached Port Hudson from various directions, they had caught the Confederates by surprise. Gardner and his men had expected an attack from the south land possibly from the east, and they had devoted nearly all their time to fortifying their defenses in these areas. An advance in part from north of Port Hudson had caught them unprepared, and the Confederates had to throw up works hurriedly.

To their great advantage, though, the terrain suited their designs superbly. The black regiments were north of Foster’s Creek, and before they could do anything, they had to pass over a pontoon bridge to get at the Confederates. South of the creek, a thoroughfare called the Telegraph Road led to Port Hudson. The problems for the attackers were that a bluff ran parallel to the road on the Federals’ left, and the Confederates had positioned riflemen there to harass troops as they crossed the pontoons and attempted to move along the road. It was virtually impossible to get at these Confederates, because the area between the road land the bluff was choppy and filled with underbrush and fallen trees. To make matters worse, a Confederate engineer had skillfully tapped into the Mississippi River and drew backwater directly through that strip between the road and the bluff. On the right side of the road was a huge backwater swamp of willow, cotton-wood, and cypress trees. To the front of the advancing troops was a bluff, well defended by Confederate infantrymen and supported by artillery.

As if the Confederate defenders needed more help, the backwater cut across the pocket between that main Rebel line and the end of the bluff that ran alongside the road, shielding the Confederate artillery from possible assaults. Had an officer with authority and any sense examined the Confederate position, the charge of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards would never have taken place.

The first assault came from troops to the east of the two black regiments, and once those blue columns failed to pierce the Confederate defense, the burden shifted to the blacks. Around 10:00 A. M. they began crossing the pontoon bridge over Foster’s Creek. Immediately a few Confederate sharpshooters peppered them with rifle fire as a warning for what was to come, but despite their losses, the black troops retained their composure. They quickly deployed as skirmishers and worked their way along the right side of the road, trying to use the timber as cover, although the swamp and felled trees delayed their advance and some Confederate artillery shells depleted their ranks.

The black regiments had hoped to rely on artillery and some white troops as support in their attack. All they got, though, were two artillery guns, which proved no help at all. After their crews hurled one round, Confederate artillery promptly silenced them with a barrage, and for the remainder of the fight they contributed nothing to the battle. Success in that sector, then, depended solely on the black troops.

Some six hundred yards from the main confederate works, amid the timber, the black regiment shifted to their left and formed two battle lines consisting of two rows each, with the 1st Louisiana native Guards in the lead. They emerged from the woods advancing rapidly, although once clear of the trees, fire from the Confederate riflemen on the bluff alongside the road now struck them in the flank and created gaps in the ranks.

As they reached a point some two hundred yards from the main works, the Confederates opened with a hail of canister, shell, and rifle fire that ripped through the lines of black troops. By dint of sheer determination, the men pressed onward to their slaughter.

When the sheets of Confederate lead staggered the first regiment, the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards joined the fray, yet their entry into the assault merely compounded the casualties. Because of the confusion on the battlefield, it is unclear how many times the two black regiments charged the Confederates.

The New Your Times eyewitness claimed that he saw six separate attacks, while both the Union and Confederate commanders on the scene counted only three. Nevertheless, the black troops demonstrated dash and courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Some soldiers attempted to wade through the backwater to get at the Confederates, and a handful of other tried to scale the bluff where the riflemen had posted themselves, to no avail.

In fact, never did the black troops seriously threaten to break through the Confederate lines, regardless of their grit. In defeat, these black troops demonstrated an inner strength comparable to that of any soldier in the Union Army.

After several charges, it had become apparent to everyone on the field that renewed attempts to take the Confederate position were insane, and eventually the troops fell back to the woods for good. Nearly two hundred black troops were casualties, some 20 percent of the two regiments, and to highlight the utter futility of the assault, they had inflicted no casualties upon the Confederates.

Despite the terrible defeat, the Battle of Port Hudson marked a turning point in attitudes toward the use of black soldiers. A lieutenant in the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards told a captain, My Co. was apparently brave. Yet they are mostly contrabands, and I must say I entertained some fears as to their pluck. But I have now none. And another officer noted, they fought with great desperation, and carried all before them. They had to be restrained for fear they would get too far in unsupported. They have shown that they can and will fight well.

From a more official viewpoint, Banks announced to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success. In concurrence, Brig. Gen Daniel Ullmann, who was in the process of raising a black brigade in Louisiana, informed Secretary of War Stanton, the brilliant conduct of the colored regiments at Port Hudson, on the 27th has silenced cavilers and changed sneers into eulogizers.

There is no question but that they behaved with dauntless courage. The New York Times, which had cautiously endorsed the limited use of black troops on a trail basis just four months earlier, now declared the experiment a success.”

Extracted from Forged in Battle Proving Their Valor The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers by Joseph T. Glatthaar, New York: The Free Press, 1990

>via: http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2013/05/27/18737451.php