In Conversation: Nadifa Mohamed

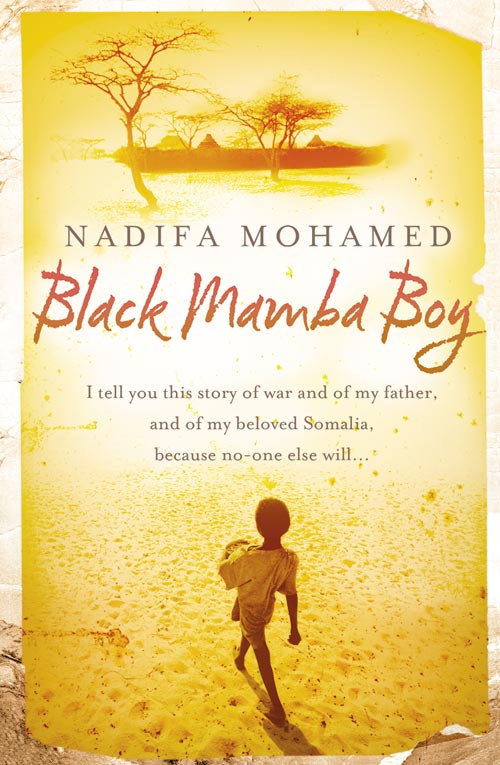

A powerful and emotionally engaging debut novel, Black Mamba Boy, which was recently longlisted for the 2010 Orange Prize for Fiction, is both a historical document and a work of fiction. Nadifa Mohamed takes us back to Somalia in the 1930s, as she tells the jaw-dropping story of her father’s life and journey. It is the story of young Jama Mohamed and his childhood journey across East Africa after the death of his mother, in search of his father – a man he has only heard of but has never met. It is a journey of self-discovery, survival, exile, dislocation, dispossession and migration that will take him through Somaliland, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Palestine and, finally, Wales. In her own words, Nadifa Mohamed’s explains the inspiration behind her novel.

Belinda: How long have you been writing and when did you come to that defining moment, when knew this is something you want to do, no matter what?

Nadifa: It was a slow realisation that I was writing something that I wanted to get published, I started writing about five years ago, basically because I wanted to commit my father’s story to paper and from there I discovered how much I, personally, got from writing.

Belinda: Let’s talk about your writing journey a little bit, are you a full time writer and when did you become a full time writer?

Nadifa: I was a full-time writer up until a year and a half ago when I started working again but with writing it’s something that you are always thinking about, working out, whatever you’re doing.

Belinda: How many stories or ideas had you already worked on and didn’t get a good response before you got your breakthrough?

Nadifa: None, ‘Black Mamba Boy’ is the first thing I have written creatively.

Belinda: What inspired Black Mamba Boy?

Nadifa: It was inspired by my father’s unusual life and I wanted to write his story but also about his generation of Somalis.

Belinda: Does the title have any symbolic meaning?

Nadifa: Yes, it is a translation of my father’s nickname. When my father was born he reminded his mother of a black mamba that had crawled over her stomach when she was pregnant.

Belinda: How long did it take to write the novel?

Nadifa: I started the novel in a cottage in Wales in 2005 and I finished editing late 2009.

Belinda: There is the art of writing and the discipline of writing, how do you combine being a writer with other aspects of life without giving one more power over the other and strike a balance?

Nadifa: What I love about writing is that it is actually enriched by the other aspects of my life; the films I see, music I listen to, the experiences I have all help me to write. You need discipline to meet deadlines but the actual creation process for me is fluid and grows organically.

Belinda: Who are your influences when it comes to literature or for their writing style?

Nadifa: I love poetic, gorgeous writing that describes the world. I am influenced probably by everything that I have read, seen and listened to, and it all comes out when you write. In terms of literature, I love lyrical writing: The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, The Electric Michelangelo by Sarah Hall, Beloved by Toni Morrison but so many others too. Banjo by Claude Mckay and Waiting For The Wild Beasts To Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma definitely affected the style of my novel.

Belinda: How would you describe your writing style and voice?

Nadifa: That’s hard! I wanted to celebrate my father’s life and wrote very subjectively because of that. The novel begins when he is a child so I wanted the innocence and adventure of childhood to come through. I also wanted the writing to do justice to the beauty of his life and environment and absorb the poetry of Somali culture.

Belinda: You father’s story serves as a lens for readers to go back in time and experience life in Somalia like we have never heard or seen it. What’s the story about Somalia and East Africa, and your background that were you keen to get across to your reader or anyone who picks up your book?

Nadifa: I was interested in exploring how life in Somalia has changed since my father’s birth and how it has remained the same. I didn’t realise that Somalis generally, and my family particularly, were so mobile. There was a huge community of Somalis in Aden but also in Sudan, Egypt, and South Africa. They grabbed at the opportunities that were presented to them and changed a lifestyle that had lasted centuries overnight, only their nomadism stayed the same. And that we have an interesting, largely unknown history that spans vast distances and that all of the horrors of the last century are an important part of our story but are not the beginning or end of it.

Belinda: You explore different themes in your book, political disorder, war, violence, dislocation and dispossession, migration among others. But it stands out that this was your father’s journey and one that has migration at its core. Was that a subject you wanted to explore based on your heritage?

Nadifa: Yes. I am an immigrant but I didn’t know that I was a third generation immigrant. My grandparents and father had also settled outside of Somalia, and in similar ways had to acclimatise to different cultures. That knowledge closed the gap between me and them. Migration is still a huge issue for Somalis, we gain and lose through it, and it was incredible to learn that from the mid-eighteenth-century Somalis have been smuggling themselves into countries that they know next to nothing about. However, I also wanted to bring attention to the negative consequences that western colonialism had on the region; the recruitment of child soldiers, dispossession of land, enforced labour, and segregation. People had to flee Somalia not just because of drought and unemployment but also because their country was not under their own control.

Belinda: How far back did you go when researching your story in order to be as accurate as you could be about the historical aspects and details of your book?

Nadifa: I went back to sixteenth-century texts because my father thought that one of his ancestors had fought with Ahmed Gurey and I wanted all of that history and mythology in the novel. Most of the historical sources I used were from 1850-1945 when Europeans began to write about the region and although they described the environment very well, they were pretty useless at describing Somalis as real people. I was ecstatic to find an autobiography by a Somali sailor written in 1929, and it was perfect. He recorded not only his physical journey but his thoughts, feelings, and experiences as well. Somali life has changed so drastically that some details have been lost as generations have disappeared, taking that knowledge with them, hopefully we can record more now.

Belinda: Did you find you were more objective when writing because you did not live in your father’s shoes and so was far removed from the situation?

Nadifa: About some things yes, I could see why my father fought for the Italians to earn a living but I also empathised with the Ethiopians who were fighting to free their country.

Belinda: You write so much about the level of poverty that was endured by many, was this a major concern for you when your father started telling you his story?

Nadifa: Yes and no, it was important for me to emphasise how much people’s poverty formed their lives because my father always impressed on me how much the hustle for survival dictated everything. However, I didn’t want the characters to be obscured by their situations; I wanted them to express their quirks, prejudices, hopes.

Belinda: What topics of discussion did you want to evoke in people with this historical work of fiction?

Nadifa: Many – identity and how it is formed when you are not rooted to a particular place or family unit, the problems that arise when young people are left to look after themselves and how patterns of abuse continue unresolved in communities.

Belinda: Why did you examine the staying power of the characters you created and their ability to endure the rough times and still have hope?

Nadifa: I am interested in how much people can survive, the human spirit is incredibly strong but also fragile. Some people, like my father, can emerge from violent, hopeless situations relatively unscathed while others are broken by much less. When I read about what is going on places like Somalia now I wonder what the actual details of peoples’ lives are, what they think about, what they dream about and hope for, this is what is missing from a lot of the narrative about Africa and other poorer regions.

Belinda: How challenging was the emotional journey as you wrote this book, it is about your father and you must have learnt a lot about him. Was it easy for you to separate yourself from the story and write objectively?

Nadifa: It really varied, sometimes the fact that the boy in the novel was a figment of my own imagination and not really my father was clear and I could separate myself from the story. At other times I was writing about situations my father had really endured and I couldn’t help but feel for him as a daughter rather than just someone who was writing a book based on his life.

Belinda: How important is it for you as a writer to bring the different kinds of emotional facets I could hear while you read at the Southbank into your work?

Nadifa: It’s crucial, to write a novel that people will enjoy and feel they have got something out of you have to access those emotions that people of whatever time or place share. It is one of the reasons that I wanted to write a novel rather than a biography, with novels you breathe life into a character, you make them whole and the reader can sink into their skin. We all feel grief, love, loneliness and every other emotion and we can identify with characters when we see them also struggling with these feelings.

Belinda: And there is the relationship between the powerful and powerless, especially with the relationship that existed in the house Jama’s mother lived in with Jama before she died and also when Jama went back to live with Jinnow and the way he was treated by the other people; was your aim to question that aspect of Somali society and society in general?

Nadifa: Yes, I came to the realisation that however poor or oppressed you are there is someone always worse off than you, and that is true in all societies.

Belinda: I noticed divides along the lines of tribesmen and family lineage, is this another issue that you found challenging to accept during your research?

Nadifa: I had to accept that there was another aspect to the Somali clan-system apart from the really terrible side we saw in the civil war. In my father’s life his clan was like a huge social welfare network that looked after members unquestioningly.

Belinda: What emotions did you want to evoke about that period in people and how they see life today?

Nadifa: Empathy, respect and wonder.

Belinda: What has the response to your book been like since it was released?

Nadifa: Incredible, I have received support and encouragement from all kinds of people.

Belinda: Have you had any negative responses since your book was released?

Nadifa: No! Luckily.

Belinda: What do you want readers to take away from the book after reading Black Mamba Boy?

Nadifa: The books I really enjoy are the ones that immerse me in a different life that let me life somewhere else as someone else for a while, I hope that my novel achieves that and my readers are taken on a journey that will extend their horizons a little.

Belinda: Your book explores relationships and friendships, what did you, as a writer, learn about your father from the friends he had throughout his journey?

Nadifa: That friendship can last a very long time! My father is still in contact with people he met in Eritrea seventy years ago, I hope that my own friendships are so strong.

Belinda: Has this book, in anyway redefined the lens through which you view your own personal history and life?

Nadifa: Yes, I look back on what my father experienced with wonder and pride, and I feel that I must be as generous to people as those who helped my father were.

Images

Image of Nadifa Mohamed: Sabreen Hussain

Black Mamba Boy jacket Cover: Harper Collins

Read my feature on Nadifa Mohamed: Telling Our Stories: Two New East African Writers

>via: http://belindaotas.com/?p=2638

__________________________

19 APRIL 2013

Granta Video: Nadifa Mohamed