I have discussed with others and argued with myself: was the seventies the greatest decade for us Black folk during the 20th century? Actually, although there have been two World Wars, the Korean Conflict, a Cold War, and Viet Nam, not to mention the 50’s initiated Civil Rights movement, there is only one other decade during the 1900’s as iconic for our people as the seventies: that decade was the twenties, so-called Harlem Renaissance era–which I generally refer to as the Garvey Era.

I believe the American establishment has, as is its usual M.O., refused to recognize our homegrown contributions to the worldwide Black liberation struggle. Hence, we get all kinds of flowers thrown at the feet of the Harlem Renaissance with very few petals dedicated to the honorable Marcus Garvey during those major years between World War 1 and the Great Depression of the thirties.

The perfidy and misdirection is so deep, that Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God is often (mis)considered the Harlem Renaissance’s crowning literary achievement although the very important book was not published until 1937, long after the Roaring Twenties and the Renaissance were long gone.

The great Langston Hughes wrote the obituary for the Harlem Renaissance in the “WHEN THE NEGRO WAS IN VOGUE” chapter of his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea. Hughes’ reminiscence was bittersweet:

I was there. I had a swell time while it lasted. But I thought it wouldn’t last long. (I remember the vogue for things Russian, the season the Chauve-Souris first came to town.) For how could a large and enthusiastic number of people be crazy about Negroes forever? But some Harlemites thought the millennium had come. They thought the race problem had at last been solved through Art plus Gladys Bentley. They were sure the New Negro would lead a new life from then on in green pastures of tolerance created by Countee Cullen, Ethel Waters, Claude McKay, Duke Ellington, Bojangles, and Alain Locke.

I don’t know what made any Negroes think that–except that they were mostly intellectuals doing the thinking. The ordinary Negroes hadn’t heard of the Negro Renaissance. And if they had, it hadn’t raised their wages any. As for all those white folks in the speakeasies and night clubs of Harlem–well, maybe a colored man could find some place to have a drink that the tourists hadn’t yet discovered.

Then it was that house-rent parties began to flourish–and not always to raise the rent either. But, as often as not, to have a get-together of one’s own, where you could do the black-bottom with no stranger behind you trying to do it, too. Non-theatrical, non-intellectual Harlem was an unwilling victim of its own vogue. It didn’t like to be stared at by white folks. But perhaps the downtowners never knew this–for the cabaret owners, the entertainers, and the speakeasy proprietors treated them fine–as long as they paid.

Back in June 1926, Hughes, the leading Black writer of the 20th century, penned in The Nation magazine the most famous essay of the era, the oft quoted “The Negro Artist And The Racial Mountain“. Moreover, at a much later time, Hughes wrote an insightful analysis of the literary contradiction he elucidated in the “racial mountain” essay–essentially, as Mari Evans would subsequently clearly state in one of her essays, — tackling the social mountain was a choice a writer could, but was not required to make.

In his 1947 essay, “My Adventures As A Social Poet” Hughes presciently wrote:

Some of my earliest poems were social poems in that they were about people’s problems — whole groups of people’s problems — rather than my own personal difficulties. Sometimes, though, certain aspects of my personal problems happened to be also common to many other people. And certainly, racially speaking, my own problems of adjustment to American life were the same as those of millions of other segregated Negroes. The moon belongs to everybody, but not this American earth of ours. That is perhaps why poems about the moon perturb no one, but poems about color and poetry do perturb many citizens. Social forces pull backwards or forwards, right or left, and social poems get caught in the pulling and hauling. Sometimes the poet himself gets pulled and hauled — even hauled off to jail.

What then are acceptable subject matters for poetry or for songs?

Entrapped on the horns of the social dilemma, Black artists in America are constantly confronted with the question Hamlet never had to answer: To be social or not to be social? But that’s the way it is with Black achievement in America. In general a social orientation is frowned upon, if not outright discouraged, if one wants to be considered a great artist.

Whether we realize it or not, the establishment teaches us that socially-oriented artwork is not as “artistic” as truly great artwork that focuses on conditions common to all of humanity. That is why Black folk can be celebrated mythically while at the same time being erased, elided, smothered, covered and appropriated to the point at which, for example, Black music ceases to need Black musicians.

But there was a time and there remains a question of authenticity (does it grow out of one’s collective as well as individual experience?) and the question of innovation (does it add to or distract from the history of a particular genre?).

In the field of African-American music, answering the questions of authenticity and innovation, ultimately requires Black musicians, or at the very least musicians who identify as an individual with the collective condition of Black people, a-la Johnny “Hand Jive” Otis, who was of immigrant Greek ancestry (born Ioannis Alexandres Veliotes) and is often erroneously considered a light-skinned Black musician.

A most significant statement is from Johnny Otis himself “As a kid I decided that if our society dictated that one had to be black or white, I would be black.” As a talent scout and musician, Otis was the first to feature Little Esther Phillips, Etta James, “Big Mama” Thornton, Jackie Wilson, Little Willie John, as well as a host of lesser famous, early Rhythm & Blues artists. In 1950, Billboard magazine crowned Otis as the R&B Artist of the Year.

There is no question that Johnny Otis was a major impresario, TV and radio personality, and, most importantly, a contributing creator of the Rhythm & Blues genre.

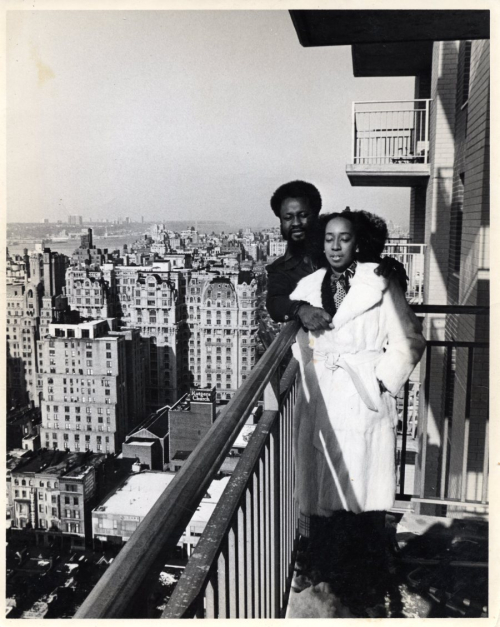

Dealing with the question of authenticity mated with social relevance, brings me to Doug and Jean Carn whose major recordings authentically reflected political and artistic developments among socially conscious African Americans of the seventies Black Power era.

Together, the couple released three albums on the Black Jazz label featuring Jean’s golden vocal work surrounded by Doug’s sterling arrangements and keyboard work.

Doug Carn was outstanding as a lyricist, penning words for some of the most moving contemporary jazz instrumentals. The albums were Infant Eyes (1971), Spirit of the New Land (1972), and Revelation (1973). A fourth album, Adam’s Apple, was released without Jean Carn. Carn’s lyrics, especially when articulated by Jean Carn, are both socially conscious and artistically impactful.

Over thirty years later in the first decade of the 2000s, Doug Carn recorded as a side-man with a number of jazz artists including Calvin Keys, Cindy Blackman, Curtis Fuller and Wallace Roney. None of those albums achieved the popularity and critical accolades as did Carn’s first three on the Black Jazz label (1969 – 1975) that featured Jean Carn on vocals.

Jean Carn would go on to change her last name to Carne and to record R&B with the Philly Soul team of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. However none of her R&B recordings were as profound or as popular as her early 70’s releases with Doug Carn.

Although many have tried, few have been able to produce instrumental and vocal jazz albums that garnered popular attention and also expressed the life affirming, socially relevant jazz-joy of Doug and Jean Carn’s first three albums.

In this new millennium the seventies albums of Doug and Jean Carn remain essential to any collection of modern jazz.

Enjoy.

Thank you for your insights. I agree.

This is been on my 2022 musical rotation,especially “Don’t Let It Go To Your Head” very timely.

RITE ON BROTHER KALAMU RITE ON.. HIT THEE NAIL ON THEE HEAD!!!!