The Power to make and to appreciate pictures

belongs to man exclusively. — Frederick Douglass

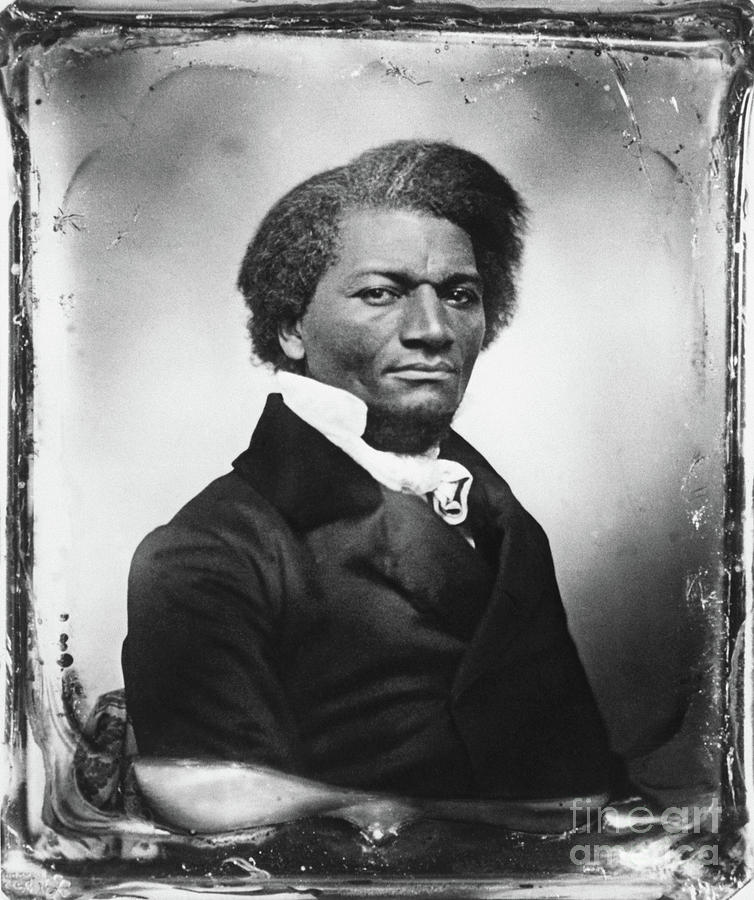

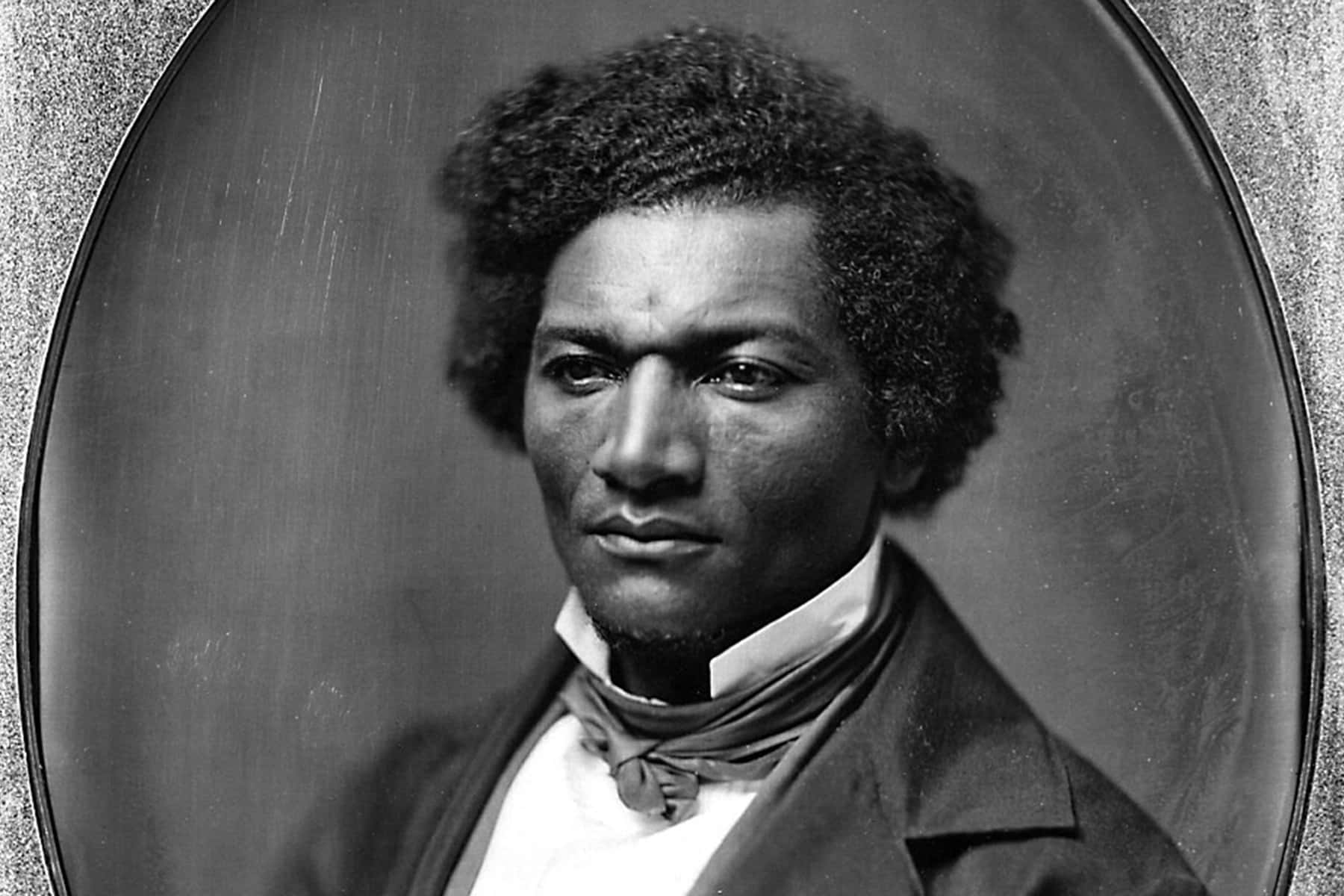

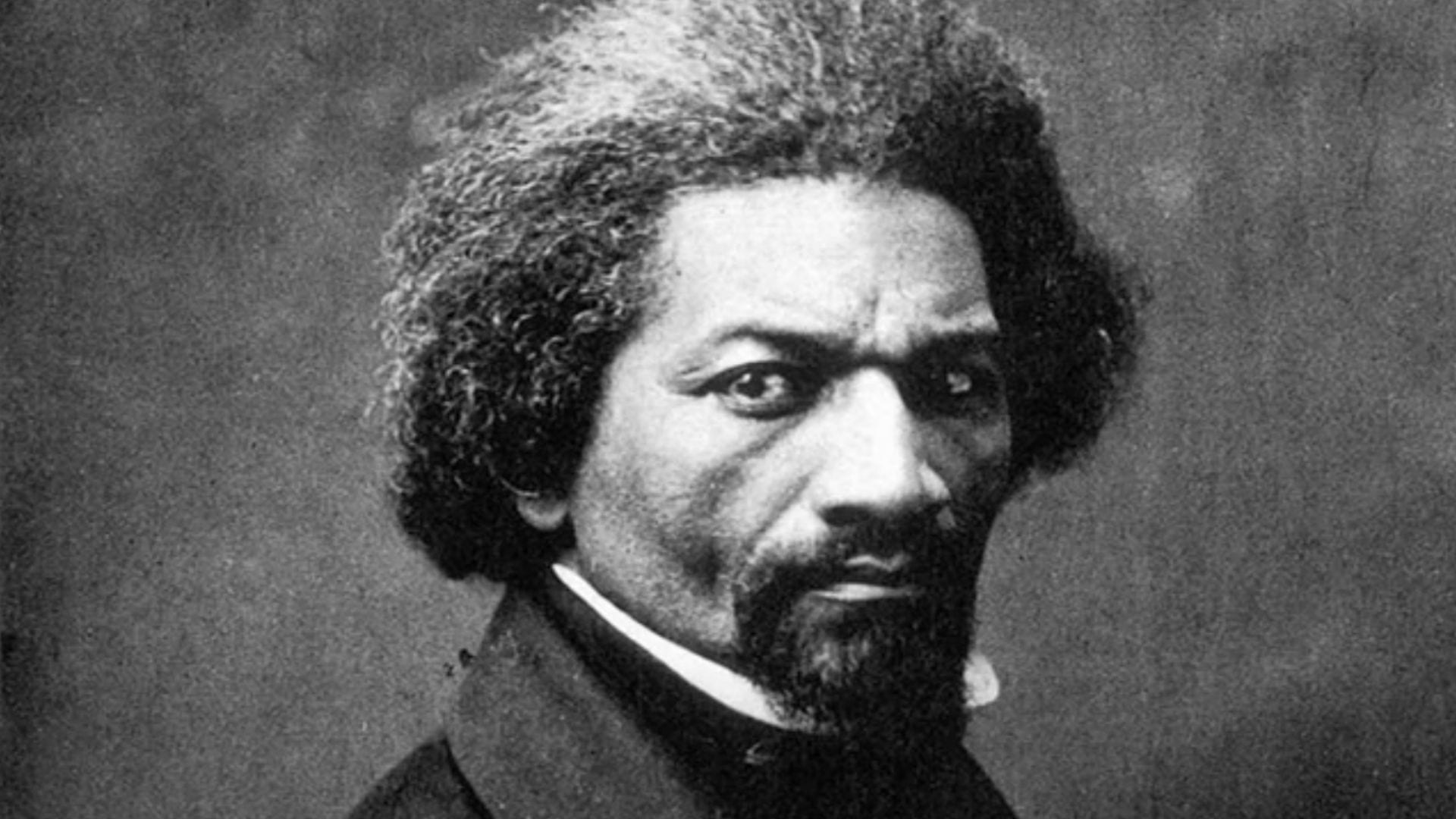

Frederick Douglass was no ordinary personality. He was extraordinary. Although enslaved when he was born, he transformed himself into a world renown orator, writer, and statesman. Throughout his adult life, he was conscious of his status and strove to present himself in the most positive light possible.

Aware of the potential impact of the then new technology of photography, Douglass sat for at least 160 individual photographs. In fact, during his era, he was the most photographed person in American history, including his contemporary, President Abraham Lincoln, who is credited with 126 different photographs.

Douglass was a full time abolitionist. In 1847 he founded a newspaper, The North Star, at a time when it was against the laws of Southern-states America to teach “negroes” how to read. Slave owners had predicted that literacy would make us unfit to be slaves, i.e. would make us rebellious.

Douglass was partially taught to read by Mrs. Sophia Auld, the wife of one of his enslavers. When those lessons were aborted by Hugh Auld, Auld’s husband, Douglass went on to surreptitiously learn to both read and write.

He used his wits to trick young Whites he encountered while doing his chores in the streets. He carried a notebook and found ways, such as offering them bread he had flinched from Mrs. Auld’s kitchen, to show him the meanings of words and phrases. According to his autobiography, the learning process took approximately seven years to complete.

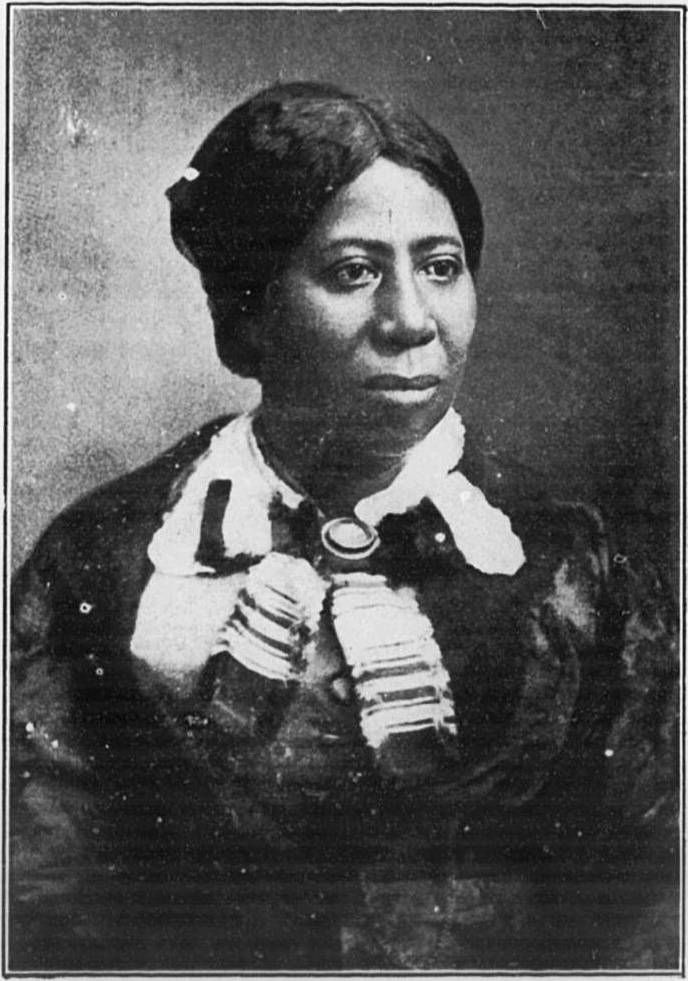

As he grew toward adulthood in the Baltimore area, he had the support of Anna Murray (March 8, 1813 – August 4, 1882), who eventually became his first wife. Murray was the daughter of a recently manumitted couple and encouraged young Douglass in his abolitionist dreams.

Through her work, she provided both funds and sailor’s clothing Douglass used to escape from slavery. Soon after arriving in New York, Douglass was approached by David Ruggles, a Black man who sheltered Douglass.

Ruggles was a free Black man and activist, a leader in the New York Committee of Vigilance, an organization dedicated to actively fighting slavery. Eventually, Anna joined Douglass in the Ruggles home. On September 15, 1838, the couple entered a forty-four year marriage.

Although she was not fully literate, Anna was an activist and willingly worked with Douglass as an abolitionist. They moved about the northeast area.

Anna turned their Rochester, New York home into a terminal of the Underground Railroad, supporting runaways on their way to Canada. Her work is too often overlooked, especially as she remained on the home front, and did not share in the limelight cast upon her famous husband.

Moreover, Anna Murray Douglass’ abolitionist work was dangerous and also unlawful in southern slaveholding states. According to the Fugitive Slave Act, harboring and abetting runaways was an offense. That Anna Douglass successfully held down the fort, as it were, while Douglass was often away from home is an amazing feat, especially when we consider that she was also the prime caretaker for their family.

Anna and Frederick were an example of a couple working as one to realize and promote the advancement of their people. Their forty-plus years of marriage and abolitionist work was more than the average lifetime of many of their contemporaries.

During their marriage they had five children: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Redmond, and Annie (who died young). Frederick was often away on speaking tours while Anna reared the children and took care of the family. After the Civil War the family settled in Washington, D.C. where Anna died on August 4, 1882.

Douglass had established himself as an activist, orator and writer. He was the author of three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845), published prior to the Civil War, 1861 – 1865; My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), often considered by scholars and abolition activists, as his master work; and, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised in 1892).

Narrative was a cause celebre and was popularly received in America and in Europe. Some questioned Douglass’ authenticity but Douglass astutely cited people, places and dates in his autobiography, effectively countering doubters.

As Douglass’ fame grew, Hugh Auld was determined to recapture Douglass. Responding to the many threats of recapture and kidnapping, Frederick Douglass decided to travel abroad. From August 1845 until just over two years later, Douglass toured Britain and Ireland. Eventually a cohort of friends and supporters “purchased” his freedom.

During his lifetime Douglass achieved notoriety as a preeminent “man of letters” in the 19th century. Certainly there was no other person of color whose published work was as influential, especially if we consider his popular speeches, such as the perennially cited “What To The Slave Is Your 4th of July”.

His literature continues to be studied well into the 21st century, and some of his noted aphorisms, such as “you may not get all that you pay for, but you will certainly pay for all that you get”, remain both accurate and popular among organizers and people struggling against systemic systems of physical, political, and economic oppression and exploitation.

Consider the circumstance: born into chattel slavery, the child of an enslaved woman and a White owner, Douglass’ lot was circumscribed and pre-ordained except he refused to submit to the standards of his time.

When he became a free man, or, more accurately, when he became a famous abolitionist asserting his right to be free, he started a newspaper, The North Star. Beyond that daring feat, he chose to speak for himself and was not content with others speaking for him or his people.

In the nineteenth century, Frederick Douglass (February 1818 – February 20, 1895), was the most recognized individual in America. Douglass set the standard for what a serious, conscious and politically active Black man looked like.

Aware of the potential impact of the then new technology of photography, Douglass sat for at least 160 individual photographs. In fact, during his era, he was the most photographed person in American history, including his contemporary, President Abraham Lincoln, who is credited with 126 different photographs.

Douglass was no ordinary personality. He was extraordinary. Although enslaved when he was born, he transformed himself into a world renown orator, writer, and statesman. Throughout his adult life, he was conscious of his status and strove to present himself in the most positive light possible.

Douglass became a full-time abolitionist. In 1847 he founded a newspaper, The North Star, at a time when it was against the laws of Southern-states America to teach “negroes” how to read. Slave owners had predicted that literacy would make us unfit to be slaves, i.e. would make us rebellious.

Douglass was partially taught to read by Mrs. Sophia Auld, the wife of one of his enslavers. When those lessons were aborted by Hugh Auld, her husband, Douglass went on to surreptitiously learn to both read and write. Douglass used his wits to trick young Whites he encountered while doing his chores in the streets. More importantly, he carried a notebook and found ways, including offered them bread he had flinched from Mrs. Auld’s kitchen, to show him the meanings of words and phrases. According to his autobiography, the learning process took approximately seven years to complete.

During his life time Douglass achieved notoriety as a preeminent “man of letters” in the 19th century. Certainly, there was no other person of color whose published work was as influential, especially if we consider his popular speeches, such as the perennially cited “What ToThe Slave Is Your 4th of July”.

Douglass was the author of three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845), published prior to the Civil War (1861 – 1865); My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), often considered by scholars and abolition activists, as his master work; and, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised in 1892).Narrative was a cause célèbre and was popularly received in America and in Europe. Some questioned Douglass’ authenticity but Douglass astutely cited people, places and dates in his autobiography, effectively countering doubters concerning the veracity of his claims.

His literature continues to be studied well into the 21st century, and some of his noted aphorisms, such as “you may not get all that you pay for, but you will certainly pay for all that you get”, remain both accurate and popular among organizers and people struggling against systemic systems of physical, political, and economic oppression and exploitation.

Consider the circumstance: born into chattel slavery, the child of an enslaved woman and a White owner, Douglass’ lot was circumscribed and pre-ordained except he refused to submit to the standards of the time.

When he became a free man, or, more accurately, when he became a famous abolitionist asserting his right to be free, he founded three newspapers:

The North Star (Rochester, N.Y.), 1847-1851 (137 issues)

Frederick Douglass’ Paper (Rochester, N.Y.), 1851-1860 (220 issues)

New National Era (Washington, D.C.), 1870-1874 (211 issues)

This is an astounding achievement of both literacy and abolitionist advocacy. Douglass understood the power of the written word. To conceive of producing a newspaper in the 19th century is one thing, to actually print and disseminate an abolitionist newspaper was no mean feat, indeed, if he had done nothing else in life, the founding of the three newspapers was a major accomplishment, a Herculean feat that few have matched.

There is another and little known side of Douglass as a trenchant social critic. Frederick Douglass presented four theoretically searching lectures on the new technology of photography. He presciently believed that photography could counter the negative images of his people flooding the mainstream circa the Civil War period.

More than simply write about the wonders of photography, he was a theoretical and cultural critic of the new image-making genre. Douglass believed that creating pictures was a human preoccupation; a way not only of reflecting the world but a means to, or at least an attempt to perfect the world.

The reality of his lectures about photography is his amazing enlightenment. He speaks as a seer, showing us ourselves, our motives, the very essence of our being. The book Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American contains three of his four major lectures on photography, presented when the 1839 art form was in its infancy and adolescence, well before it’s twentieth century development and twenty-first century maturation.

Picturing Frederick Douglass includes numerous photos and illustrations, and additionally contains transcriptions of the important essays: “Lecture on Pictures” (1861), “Age of Pictures” (1862), and “Pictures and Progress” (1864–65). Even today when the camera on smart phones is ubiquitous, few of us are learned enough to theorize about photography.

Speaking of the tremendous import of Daguerre’s invention of photography, Douglass enthusiastically noted:

Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them. What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all. The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures, could purchase fifty years ago.

Douglass – “Lecture on Pictures” (December 3, 1861)

More than simply write about the wonders of photography he was also a theoretical and cultural critic of the new image-making genre. Douglass believed that creating pictures was a human preoccupation; a way not only of reflecting the world but a means, or at least an attempt, to perfect the world. One of the main goals and great good of photography is to see the world and all that is in the world not simply as we imagine, understand, or even as it appears to us, but rather as the world in truth is.

The photographic faithfulness of our pictures, in delineating the human face and form, answers well the stern requirement of Cromwell himself. “Paint me as I am,” said the staunch old Puritan. The order reveals perhaps quite as visibly his self-love as his love of truth. The huge wart on his face was probably, in the eyes of the great founder of the English Commonwealth, a beauty rather than a deformity. But in any case we are bound to respect the requirement.

Douglass – “Age of Pictures” (1862)

The reality of his lectures about photography is his amazing enlightenment. He speaks as a seer, showing us ourselves, our motives, the very essence of our being. However, in speaking of photography, Douglass also makes an essential observation:

The process by which man is able to posit his own subjective nature outside of himself, giving it form, color, space, and all the attributes of distinct personality, so that it becomes the subject of distinct observation and contemplation, is at [the] bottom of all effort and the germinating principles of all reform and all progress. But for this, the history of the beast of the field would be the history of man. It is the picture of life contrasted with the fact of life, the ideal contrasted with the real, which makes criticism possible. Where there is no criticism there is no progress, for the want of progress is not where such want is not made visible by criticism. It is by looking upon this picture and upon that which enables us to point out the defects of the one and the perfections of the other.

Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflections of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.

Douglass – “Pictures and Progress” (circa 1864/1865)

Clearly, Frederick Douglass is a philosopher. He argues that photography not only enables us to see the reality of people and objects, but more importantly also enables us, through learned criticism, to consciously critique that which is in contradistinction to what ought to be. For Douglass, photography not only shows us what is, photography also primes us to critique what isn’t, and to long for, work toward what ought to be.

Douglas was no simpleton, nor was he a narcissist in love with his own image spied in the hundred-plus images of himself he sat for during his lifetime. Douglass is the philosopher who knows that a truthful picture shatters all specious propaganda on the one hand, simply by presenting the truth, but, and even more importantly, truth enables us to critique what is and simultaneously strive for what we think ought to be.

According to Douglass we are not only picture making and picture appreciating creatures, at our best we are also picture creators. A truth picture allows us to envision creating a more ideal picture that more closely conforms to our desires, our conceptions. How one looks is one thing, how one appears to others is another. The goal is to bring the truth and the desired appearance into registration, i.e. to make them one and the same.

Although it is a fact that photography pictures the truth, in the 20th century we discover that even photography distorts the truth depending on the lens used to view and capture the object, as well as the quality of the equipment and the method of reproduction, or any number of other issues (lighting, movement, perspective, etc.).

That Frederick Douglass was both wowed by photography as well as appreciative that photography could be one of the ultimate abolitionist tools is at the core of his arguments about the value of photography. Photography made it possible to escape illusions, made it possible to represent the truth, or should we say, come closer to representing the truth than could a painting or a drawing.

In the 19th century and beyond, the truth of who Black people were and are is a major American issue precisely because so much propaganda and demeaning displays had been issued about us. Indeed, lies were presented as truth. Douglass saw that photography had the power to destroy lies.

Douglass also saw that photography was capable of generating feelings as well as ideas. In one of his profound summations Douglass noted in Lecture on Pictures (1861) that “Only a few men wish to think, while all wish to feel, for feeling is divine and infinite.”

We assess a picture as powerful, not only because of what it makes us think, but rather because of how it causes us to feel—and feeling a certain way can cause us to appreciate or to dismiss a reality whether that reality is dimly or perceptively perceived. When one reads Douglass exegesis on photography, whether we fully understand what Douglass means, we can use our own responds to understand the feelings generated by a photograph, whether that photograph is a quick snapshot or a fully composed, artistic rendering.

Douglass deals with far more than mere appearance, he is concerned with the social meaning of image making and with the value of the image as time passes on.

What is most striking about Douglass’ understanding concerning photography is that in making his arguments, Douglass displays a breadth of learning. His ability to read and write were far beyond utilitarian. Indeed, Douglass lived in the realm of “thinking about things”—the whys and wherefores of existence.

Picturing Frederick Douglass includes numerous photos and illustrations, and additionally contains the important essays: “Lecture on Pictures” (1861), “Age of Pictures” (1862), and “Pictures and Progress” (1864–65). Even today when the camera on smart phones is ubiquitous, few of us are learned enough to theorize about the meaning, impact and social use of photography. It is extremely important to recognize that his four essays on photography were all written during the Civil War period, an era when the new technology was used to bring home the horrors/the reality of war. Arguably, beyond famous men of the era, the most impressive photographs that many Americans saw were images of war.

From the very beginning, Douglass peeped the potential power of the photographic image and sought to understand its dynamic reach into the human soul. Douglass used himself as both a model for and an example of what could be achieved by portrait photography.

With his impressive lionized coiffure–what would in another century be characterized as a massive afro–and his steely gaze—no smiling, no grinning, no comedic buffoon–Frederick Douglass exemplified the “New Negro” well before the 1920s Garvey Era/Jazz Age had yet to arrive. Douglass saw the future. Moreover, he wanted friend and foe to know what he saw. His stern visage was a portent of the shape of Black portraiture to come.

Douglass and grandson Joseph – October 31, 1894

by Black photographer James E. Reed