When I was in sixth grade at Phillis Wheatley school, around the corner from the Dooky Chase restaurant, back in the fifties, I had class mates who routinely passed for White after school. We got on the New Orleans public transportation busses together, headed to Canal Street, where the main shopping and business district was.

One of the widest streets in America had trolley cars running up and down the median and was lined with stores and offices on both sides. The thoroughfare also was the place where the majority of the diverse bus lines from both uptown and downtown would meet and turn around. Additionally, Canal Street was an accessible and common meeting location known to most New Orleanians. “I’ll meet you by. . .” such and such store, corner, or bus stop. . . “you know, where the Peanut Man be.”

Pamela, Gilbert and a number of other friends boarded and sat in front of the screens; we trooped on to the back (occasionally one of us would throw a screen out the window). The wooden plaques had metal pegs on the bottom that fit into holes on the tops of bus seats. When Whites boarded the buses, if there were no open seats available, they would lift the screen and move it to seats further back. Blacks who were seated in front of where ever the screen was moved, were obliged to get up and move to a seat behind the screen. If there were no empty seats behind the screen, you had to stand. Segregation wasn’t nothing nice.

When I saw the movie Passing, based on the short novel by Nella Larsen that focused on former childhood friends who had both grown up to become women of means in New York City (one living in Harlem, the other visiting while her husband was doing business) during the Jazz Age twenties, Jim Crow memories sullied my consciousness.

The moneyed among us was a tiny minority within a minority. Petite bourgeois class components were even more glaring to me than were the obvious racial conundrums. In no particular order, racial, and in some cases racist, elements twirled around as if on a merry-go-round, class issues were ignored, and the supremacy of patriarchy was assumed.

In that situation, if you are Black, poor and female, you silently did the work while saying little if anything besides “yes, mam” or “no, mam” and “yes, sir” or “no, sir”.

This austere black and white movie is never solely what it seems to be. The cinematography is rich in its shadings that reveal tensions while hiding secrets. The color white dominates throughout and especially so in the conclusion in the snow that is immediately followed by a white-out ending.

Significantly, in the personal aspects of Irene’s life, blackness dominates. Check the skin tones, especially of her children; the dark interiors of her home, which are never portrayed as menacing or forbidding but rather as natural and comforting. In contrast to Clare, who luxuriates in Irene’s world, Irene is made ill by the pretense and contradictions she chooses to endure. This is a subtle and devastating subversion of a placid surface covering an interior life full of turmoil.

The aesthetics of the film present the color white as a source of conflict and the color black as a source of comfort. Whiteness dominates the setting when Irene and Clare are first reunited in a hotel restaurant. Most significantly, upon inserting herself into Irene’s domestic life, Clare is shown now obviously feeling at home; easily interacting with Irene’s children; quietly conversating with Irene’s husband; sitting in the back yard, sharing a relaxing, Indian summer afternoon with “Zu” (i.e. Zulena), who is Irene’s dark-skinned maid.

Obviously the director paid particular attention in employing a color palette on which white is presented as sterile and darker shades as fecund. The dialogue is sharp, always peeling back an exterior to reveal the true, albeit hidden, meanings of words, individuals, situations. In the light of darkness we are shown the realities of black, white, and various shades in-between.

Significantly, the soundtrack features solo piano passages by Ethiopian pianist and composer Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou. In the Harlem party sequences jazz predominates, especially when a raucous trumpeter joyously subverts the nuances of the film’s thematic music. The director’s musical choices are no accident. European elements are not presented, instead African and African-American musics provide a tapestry of meaningful sounds.

The scriptwriter and director, Rebbeca Hall, whose grandfather passed for white, has produced a subtle expose of the dangers of passing, particularly when one is outed. Preceding the tragic conclusion, rather than deny or denounce her Black interior, Clare escapes her racist, husband’s wrath the only way she can. He has accused her of being a liar and as he advances in demonic rage, she flees, or is she pushed?

However, before we get to the conclusion, we have to negotiate a maze of psychological feigns and thrusts. This movie is far from a one-trick pony, especially in the interrogation of the behaviors and intentions of the duo of leading women.

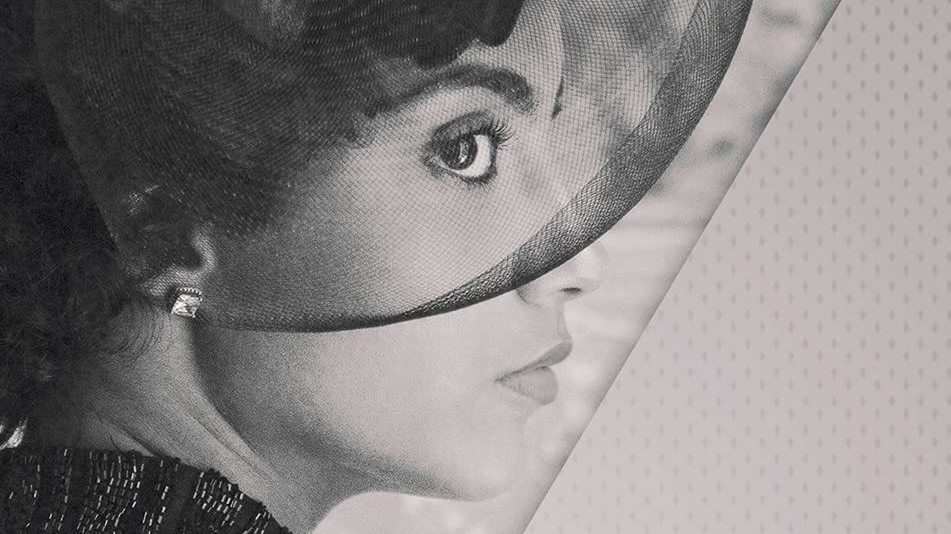

1. Repressed Irene Redfield, brim of her hat pulled down, hiding who she thought herself to be: a Black self, she presumed, Whites would peep if she weren’t careful when around them; a self-manufactured identity that was a paragon of both progress and psychosis. She was a light-skined stalwart of racial uplift organizations and, at the same time, mortifyingly afraid of exhibiting real feelings for her family, or displaying the actualities of her social status, and she especially had a reluctance to reveal her deep, complex, and often contradictory notions of self-identity.

2. Libertine (although far from liberated) Clare Kendry is a sell-out who furtively longed to return back as an in-sider. She dyed her hair blond but it was no permanent cover for her unfulfilled desire to actualize her authentic Black self even though she had chosen to live White. She had it all and still wanted more–what more? Why, dreams of Black freedom. How “they” danced through life. She stood the tragic mulatto on her head, desperately wanting both to enjoy the fruits of a forbidden White lifestyle and to be true to her own Black self.

3. Irene, talking around having “the talk” with her two sons, both of whom were too dark to ever pass; trying to keep her physician husband who wanted to escape from home by sailing off to Europe; engaging with a “colored” maid who keeps the homestead working; and, most of all, bereft of friends with whom she could engage in honest girl talk.

Reenie is truly a bird trapped in a gilded cage. In a passing moment of frank, to the point of bitter, conversation with acclaimed writer Hugh Wentworth (played by Bill Camp), Irene momentarily drops her guarded speech and reveals the vapidness of material success, noting that in one way or another we are all passing for something we are not.

4. Clare, the blond bombshell, is always on the verge of exploding. She has a daughter, whom we never see and who is sent off to Europe for an education. Another complexity is the deep, subliminal lesbian desire (including kisses and discrete touches) between the former classmates; the taboo feelings are evident and evidenced in exchanges between the duo who are friends “without” benefits.

In different ways they both desire to “be” the other, while at the same time, for divergent reasons, they are frustrated as they elect to never actually fulfill their mutual desire to “be with” each other. Nevertheless, Clare articulates that if her deception is discovered, then she is willing to move in with Irene (and with Irene’s husband, children and all). That hopeless situation would be a dream that would quickly curdle into a mishmash nightmare.

This austere black and white movie is never solely what it seems to be. The cinematography is rich in its shadings that reveal tensions while hiding secrets. The color white dominates throughout and especially the conclusion in the snow that is immediately followed by a white-out ending.

Significantly, in the personal aspects of Irene’s life, blackness dominates. Check the skin tones, especially of her children and husband; the dark interiors of her home, which are never portrayed as menacing or forbidding but rather as natural and comforting. In contrast to Clare, who luxuriates in Irene’s home, Irene is made ill by the pretense and contradictions she chooses to endure.

The aesthetics of the film present the color white as a source of conflict and the color black as a source of comfort. Whiteness dominates the setting when Irene and Clare are first reunited in a hotel restaurant. Most significantly, upon inserting herself into Irene’s domestic life, Clare is shown now obviously feeling at home; easily interacting with Irene’s children; quietly conversating with Irene’s husband; sitting in the back yard, sharing a relaxing, Indian summer afternoon with “Zu” (i.e. Zulena), who is Irene’s dark-skinned maid.

Significantly, in a nod to Ruth Negga’s paternal Ethiopian heritage, the soundtrack features solo piano passages by Ethiopian pianist and composer Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou. On the other hand, the film also offers Harlem party sequences, including a raucous, jazz trumpet solo, which joyously subverts the nuances of the film’s thematic music. The director’s musical choices are no accident. European elements are not presented, instead African and African-American musics provide a tapestry of meaningful sounds.

The scriptwriter and director, Rebbeca Hall, whose grandfather passed for white, has produced a subtle expose of the dangers of passing, particularly when one is outed. Preceding the tragic conclusion, rather than deny or denounce her Black interior, Clare escapes her racist-husband’s wrath the only way she can. He has accused her of being a liar and as he advances in demonic rage, she flees, or is she pushed?

The climatic denouement of the movie features figures trotting up six flights of stairs to offer salvation only to conclude with Clare flying out of an open window, falling to her death.

As is the case throughout both the book and the movie, ambiguity reigns. When one attempts to live as other than what we are, clear cut clarity is never achieved. Was Clare’s death a suicide, a homicide, or just an accident. Except for an insightful explanation by Lucas Blue, most of the many reviews I’ve read do not highlight nor definitively explain the meaning of this morbid and ambiguous ending. Indeed many reviews of the movie do not even acknowledge Clare’s death.

For African Americans of that era, the cost of living White was to kill the Black self. Dr. DuBois perceptively diagnosed the problem:

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line, the question as to how far differences of race-which show themselves chiefly in the color of the skin and the texture of the hair-will hereafter be made the basis of denying to over half the world the right of sharing to utmost ability the opportunities and privileges of modern civilization.

In Passing the racial, class, and gender issues and conflicts are subtly presented even when explicitly alluded to. This was the end of an era: circa 1929–the beginning of the great depression and also the publication year of Nella Larsen’s dystopian novel the secret of which is that nothing is what it appears to be or, to put it another way, appearance is no substitute for substance.

Divorced from the social issues of their time period, the conflicts raged internally: sickening Irene and killing Clare. Thus, illustrating the tragedy Fanon so famously explored in Black Skin, White Masks, except here the masks are “light skin” and upper class financial largesse–money is not a problem for either woman, yet life is unbearable for both.

As this movie makes clear, regardless of how high up the social ladder we ascend, we seldom fully escape. Given accidents of birth, regardless of what side of the fence we gravitate toward, the deadly gravity of White supremacy eventually touches, and in far too many cases, entraps us–and that is especially the case for those of us who believe the self-delusion that we have somehow successfully evaded the terror.