The weather was cold. Gray. Snow on the ground. A typical London winter. Somewhere in the metro north of the city. No nearby metro or bus stop. I had never been in that neighborhood before nevertheless I kept marching forward. Eventually I found the flat and met the ANC (African National Congress) representative. This was the late seventies or early eighties.

We had a welcomed and warm meeting. Literally in front of a flaming fireplace. At one point I enthusiastically acknowledged that we in the United States were inspired by the South African struggle. He stopped me. I don’t remember his name but he insisted that rather than them inspiring us, the truth was our struggles in the sixties had inspired them, our far away cousins.

I was an activist with a long history of take overs at SUNO (Southern University in New Orleans), sit-ins at the New Orleans city hall, and as a delegate to the 1974 Sixth Pan-African conference in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. I was not a star struck political neophyte.

After years of both study and struggle I was impressed with a number of resistance movements including Amilcar Cabral’s PAIGC and Nelson and Winnie Mandela’s ANC. I was offered the opportunity to meet with a senior representative of the South African liberation movement, which was why I had trekked to this meeting with a previously unknown person. We sat, just the two of us, in an impromptu but unforgettable tete-a-tete.

Decades later and well into another century, I no longer consider myself a Black nationalist. I have seen too much as both an activist and a journalist to believe in limited solutions to international political, economic and gender problems, particularly in the Middle East.

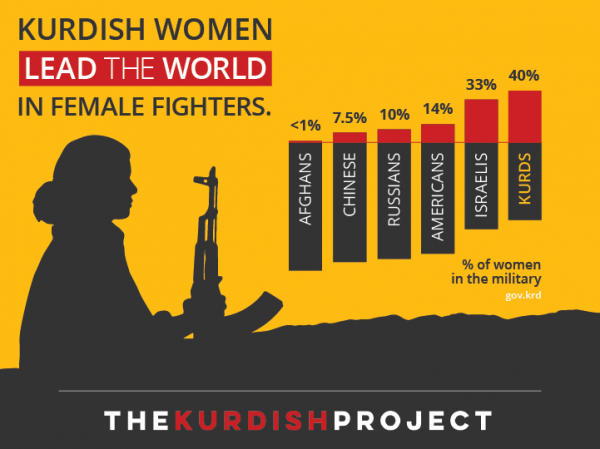

When I became aware of the Peshmerga (“those who face death”) branch of the Kurdish struggle, I was struck by the high degree of female participation as fighters and leaders in their fight for independence.

Moreover, the ups and downs of their decades long movement was an example of indigenous organization that was not based mainly on either religion or one-state ideology. Approximately 30 million stateless Kurds were spread out over four separate Middle East countries, all four of whom had both internal problems as well as differences with each other.

What really struck me was the degree of female participation in the Kurdish struggle. Based both on the ground-level reports from the trenches and foxholes on the battle field to intellectual analysis offered by committed pro-Kurdish advocates, my resulting understanding of the Kurds impelled me to write and share my views.

Historically, the main leaders of African heritage armed struggles in the western hemisphere have been women. Whether talking, for example, about Nanny in Jamaica or Harriet Tubman in the USA, women were not only fighters in individual struggles but were indeed locally, nationally, and even internationally recognized leaders.

In more contemporary times I had been blessed to spend time with Assata Shakur in Cuba. Life experiences and study have predisposed me to favor female participation as an indispensable element of anti-establishment activism. Like many who initially were strong advocates of Black nationalism, worldwide realities led me to move beyond race as the major ideological definition.

In our seventies organization, Ahidiana, we had a saying: “if we are wrong reality will contradict us, and if we are serious we will correct ourselves”. The volatile Middle Eastern struggle, and particularly the example of guerrilla women, spurred me take the Kurdish struggle seriously.

Make no mistake. The female Peshmerga women are a committed cadre of soldiers who were among the leaders in active battle against ISIS. The Peshmerga are a military force from the northern region of Iraq founded in the 1920s. They have been fighting for generations and even when betrayed, they are not about to surrender.

They do however face daunting odds. They have no heavy weapons, e.g. no tank squadrons, no major artillery, no air force, and most significant in the long run, no atomic bomb (plus, no way to make or deliver atomic weapons even if they had them).

The Kurdish army is basically an infantry during an era of modern warfare, which is why they are no match for the Turkish assault. They can not hold territory, can not defend towns and cities for any length of time against enemy encroachment. They are unable to protect large civilian populations. While it is true that they were leaders in the fight against ISIS, that struggle was predominately house to house, hand to hand combat between infantry forces. What the Kurds have is a will to resist, to fight to the death.

In October 2019 when Trump announced that he was abandoning support for the Kurds that was a major turning point in this conflict. A turning point but not an end. The Kurds have literally seen nations come and go. They deserve our support. But with or without diplomatic and military support, they will continue to struggle. They are an inspiration to the world.