Context. Context. Context. That’s what counts in writing about historical developments; especially so, in the case of something as elusive as jazz. Not only the epistemological question: what is jazz? But the even more daunting dual inquiry: where did it come from and where is it going?

At the Professor Longhair symposium, I raised up my pinkie finger and stuck my big toe (briefly/quickly) in those swampy albeit swiftly flowing waters. Swampy in that on some levels, particularly when you try to analyze and understand the music, the whole thing is a morass, a mixing and merger of confounding, and often conflicting, if not utterly confusing, elements.

For example: a black man playing a piano, singing in a jumble of English vernacular and diverse patois (English, French, Native American and god knows what else), vigorously employing so-called Latin rhythms! Really ought to specify that the “Latin” elements ought to be spelled African (with a capital “A”). Ah, but I digress.

Our culture is a culture of change, or as Baraka aptly dubbed it: the changing same. Especially the music, which is a kaleidoscope of ideas and feelings expressed sonically. And it all be happening so fast, most of us have to run just to stand still. Think about what running with the pack means, and how everything is cool as long as your fast is keeping with their slow, or vice versa. Whatever, front or back, just stay with the pack. But if you slow down… well, that’s not advisable when hanging with the big dogs.

Anyway, this essay about the two-cradle theory is really just a ta-ta, a little taste. Hopefully in the next year or so, I’m going to write out from A to Z–Afro/Latin to Zydeco–the whole, wonderful, whirlwind of sounds that black music in the deep south has become.

The “Two-Cradle Theory Of Jazz” essay below was presented in a significantly shorter form and without the photographs as a keynote address for the Professor Longhair Symposium on April 12, 2019 in the auditorium of the New Orleans Jazz Museum located in the old U.S. Mint on the edge of the French Quarter, 400 Esplanade Avenue at the river (i.e. the mighty Mississippi River). Some of the most interesting observations came up during the question and answer dialogue that followed the formal presentation.

–Kalamu ya Salaam

A Two-Cradle Theory Of Jazz

The popular notion that “jazz” started in New Orleans has been challenged not by an argument that some other specific location was the birthplace of jazz, but rather that jazz was found throughout the United States following reconstruction at the turn of the century. My initial reaction—as I’m sure was the reaction of many jazz aficionados—was that such a notion was prima facie ridiculous. Everybody knows that the Crescent City is the birthplace of jazz.

But being somewhat intelligent, I literally listened to an online summation of the argument put forth in a book titled: Jazz on the Barbary Coast by Tom Stoddard. The central argument revolves around the Barbary Coast, i.e. turn of the 20thcentury San Francisco as a thriving center of jazz music at approximately the same time as jazz was credited as starting in New Orleans. The book cites relatively obscure musicians such as Sid LeProttie, Reb Spikes, Wesley Fields, Alfred Levy, and Charlie “Duke” Turner.

While the “not only New Orleans” crowd argues that jazz did not have a singular birthplace, they do believe that the original creators were black musicians. They assert that original jazz was played all over America from New York city to San Francisco, literally the breadth of the United States.

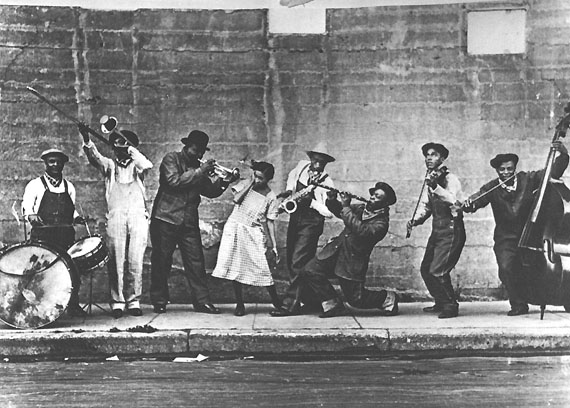

Of course, I was familiar with the famous 1921 photograph of King Oliver’s band on a street in San Francisco. The band is composed of Ram Hall, Honore Dutrey, King Oliver, Lil Hardin-Armstrong, David Jones, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Palao, and Ed Garland. Most of those musicians were New Orleanians.

While I’m always intrigued by the fact that King Oliver was gigging out on the west coast back in the twenties, while that photograph established that King Oliver and cohorts were in San Francisco, however the street shot does not prove that San Francisco was one of the birthplaces of jazz. Indeed, the photograph is actually more support for the proposition that jazz was a New Orleans product. It seemed to me much more probable that New Orleans musicians had traveled to San Francisco rather than jazz being born in San Francisco and elsewhere.

The 1921 date is significant because one of my related central arguments about the blues is that the iconic itinerate country blues musician traveling from place to place, especially in Mississippi as well as throughout the deep south, was not likely to be the case in virulently segregationist, antebellum Dixie. I don’t believe negroes were allowed to walk around playing guitars instead of picking cotton and doing other forced labor during that time period. Of course, that is an exaggeration but I think the point of my objection to openly mobile blues musicians pre-civil war is clear.

Whatever and whenever early jazz occurred, it was certainly not before the period of reconstruction, which incidentally is the period of America’s musical history that saw the rise of the music called ragtime. The most famous ragtime musician was Scott Joplin, who was born in Texarkana, Texas, November 24, 1868 and died in New York City, April 1, 1917. It is inconceivable, although not impossible, that jazz preceded ragtime.

Lt. James Reese Europe, left, arrives in New York with the 369th Infantry, commonly known as the “Harlem Hellfighters, ” following the conclusion of World War I. On that day in 1919, the infantry unit was treated to adoring cheers throughout the streets of Manhattan.

A contemporary of Joplin was James Reese Europe, who in my estimation, ought to be as celebrated as Scott Joplin. Jim Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1881 and moved while a youngster to Washington, DC in the beginning of the 1900s. As noted by the Library of Congress:

In 1910 Europe formed the Clef Club and became its president. This organization not only put together its own orchestra and chorus, but served as a union and contracting agency for black musicians. Soon it had as many as 200 men on its roster. On May 2,1912, the Clef Club Symphony Orchestra put on “A Concert of Negro Music” in Carnegie Hall. The concert was a tremendous success. The 125-man orchestra included a large contingent of banjos and mandolins and presented music by exclusively black composers. By this time, Europe believed that although black musicians respected white music of quality, they did not need to play or imitate it. Instead they had their own music to play which people of all races would want to hear.

Europe left the Clef Club in 1913 and formed another organization, the Tempo Club. The new club served much the same purpose as the Clef Club–booking black musicians for the dances which were sweeping New York City social life. In 1914 Europe formed an association with the popular dancing duo Vernon and Irene Castle. Europe invented the turkey-trot with the Castles, and the fox-trot, which is still popular today.

Europe also made a series of recordings in 1914 for the Victor Record Company. These recordings show that Europe’s music was like no other music produced at that time or since. Neither jazz nor ragtime, the recordings combine complex melodies and arrangements with driving rhythms. One of these sides, the “The Castles in Europe One-Step (Castle House Rag),” was named to the 2004 National Registry of Recordings.

When World War I became a reality for America, James Europe signed up and was commissioned a lieutenant for the 15th Regiment under Colonel Hayward. He was ordered to put together the best band he could muster, and he did so, going as far afield as Puerto Rico to find the musicians he wanted. His friend Nobel Sissle served as his drum major. This regiment became the 369th Regiment, known as the Hell Fighters, and proceeded to amaze continental Europe–especially France, with its brilliant and original music. Some French musicians, reading from the band’s parts, tried to duplicate Europe’s band sound but could not, which only caused their admiration to increase. In an interview, Europe graciously acknowledged this appreciation and attributed it to the fact that his musicians played their own, black music. Europeans, he argued, simply recognized his music as good because it was original and intrinsically worthy as music.

The United States press did not fail to notice Europe’s fame overseas and he was welcomed home in 1919 as a hero. He immediately embarked on a tour with his Hell Fighters band and played one show in New York to rave reviews. Just before the next show in Boston, he was knifed in the neck by a drummer in his band, Herbert Wright, over the latter’s delusion that Europe had cheated him. Europe appeared only slightly wounded. He ordered Sissle, who had helped subdue Wright, to carry on in his stead while he went to the hospital. The wound, however, was fatal, and Europe died within an hour. Nobel Sissle later wrote an unpublished memoirof Europe, which is available on American Memory.

Note that Jim Europe was at the height of his career when he was killed in 1919, which is within the same time period referred to by the Barbary jazz proponents and is consistent with what is often cited as the rise of jazz in turn of the century New Orleans. Indeed, it was only a handful of years later that the first “talkie” (feature-length movie with synchronized sound) came out. This infamous, so-called classic, 1927 Hollywood movie was the “Jazz Singer” featuring Al Jolson. I say infamous because, in this case, the jazz singer was a Russian born jew, Asa Yoelson, who performed in black face. Based on that fictionalization of history, the music of jazz was introduced to the majority of Americans by a non-native.

The early years of jazz are shrouded in mystery as is the word itself. How jazz got its name and who named it are subjects of debate and conjecture but no conclusive information has thus far been found.

Indeed, even what we do know about jazz is hotly debated. Did jazz start in the brothels of New Orleans shortly after reconstruction or was the true home of jazz in the black neighborhoods of New Orleans? Or was jazz a result of the mixture of rough uptown Negroes and the more genteel denizens of creole downtown New Orleans who were people of color who had lived in New Orleans for generations prior to the civil war?

Ragtime is primarily remembered as piano music, and was often featured on player pianos with mechanical piano rolls that could play in a manner that was difficult for many traditionally trained pianists to master. On the ensemble side of the street, America was entranced and enthralled by the military style music for marching bands by John Philip Sousa. Significantly, Sousa is credited with this revealing, ironic quote from someone who was not known as a jazz musician: “Jazz will endure just as long people hear it through their feet instead of their brains.”

The piston-like stepping of the traditional marching band was easily out classed by the second-line music and movements of New Orleans brass band music. The transition from jazz funeral music to both modern jazz (bebop, post-bop and fusion) and R&B influenced modern second-line music was introduced by the Dirty Dozen Brass Band. Their early hit was their anthem, “My Feet Can’t Fail Me Now.” This was dance music for the street rather than for the dance floor.

The Dirty Dozen is a direct descendant of bands like the Tuxedo or the Olympia Brass bands. The Dozens (as they are popularly known) introduced the energetic modern jazz and contemporary R&B stylings into the brass band repertoire. Initially, the transition went from ragtime to traditional jazz, but that development was followed by an even more radical transition initialized by the Dirty Dozen which was as likely to play bebop tunes and riffs as they were to funkify much older songs like “Little Liza Jane.” The wide-ranging, eclectic selection of songs endeared the Dozens to musicians, second-line dancers, and people partying at the Glass House, which was their home-base on Saratoga Street, uptown in Central City New Orleans. This aggregation actively illustrated how the music constantly moves.

Back in the day, when jazz was in its infancy (and often spelled “jass”) I believe the migration from piano-based ragtime to brass band jazz happened in Lincoln and Johnson Parks located in uptown New Orleans near present day Xavier University. The two blocks of Carrollton bounded by Fern, Forshey and Oleander streets was where the parks were located, adjacent to each other.

The main progenitor and jazz’s most legendary figure was Buddy Bolden. Don Marquis’ book In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man Of Jazz (1978) identifies the activities that occurred in the two parks. Buddy Bolden would hold court at Lincoln Park blowing away any and all competition at the neighboring Johnson Park, where John Robichaux’s Orchestra often held forth. Sunday afternoons were documented as lively affairs full of fun and frolic, well, at least until cornetist Buddy Bolden called his children home blowing his loud, blue-saturated music. Robichaux’s more refined ensemble failed to hold the attention of the assembled revelers. This was approximately 1900 to 1910.

Buddy Bolden, second from left in the back row, holding his cornet

Although much about Charles Joseph “Buddy” Bolden (September 6, 1877 – November 4, 1931) is in dispute, he is widely acknowledged as the first well-known jazz musician. His stomping grounds was uptown New Orleans in what is now Central City, not far from Johnson Park. King Bolden is considered by many, including Wynton Marsalis, to be the musician who modernized the music that developed into jazz by introducing what became known as “hot rhythms”. Meanwhile the piano kings were cutting up in barrooms, taverns, parlors, and on tailgates with pianos literally ensconced on the beds of trucks.

This time period of the early days of jazz also accords with both the rise and the demise of Storyville, the infamous red light district of New Orleans, noted for its nightlife (including brothels) and for its music. Founded in 1895, Storyville was closed by the department of the navy in 1917.

It is significant that Henry Roeland Byrd, also known as Roy Byrd, and better, and most famously, known as Professor Longhair was born December 19, 1918 in Bogalusa, Louisiana. He moved to New Orleans as a child and never took up residence outside of the city.

Tony Jackson

Longhair is one of the most famous of the long line of New Orleans pianists. The line of royalty stretches back to Antonio Junius “Tony” Jackson (October 25, 1882 — April 20, 1921) who is credited with composing the song “Pretty Baby” in 1916. Mr. Jackson was an out gay man who was considered a piano king of Storyville. His life and legend is undoubtedly one of the sources of the myth that jazz was born in Storyville.

Jelly Roll Morton

The most famous of the piano kings was the loquacious Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe, who is more popularly known as Jelly Roll Morton. Born October 20, 1890 in New Orleans, he traveled widely and often, including out to the west coast where he died July 10, 1941 in Los Angeles. His recordings for the Library of Congress are considered quintessential because not only is his music well documented but he also talked extensively about his life and musical career.

From this brief time line, it is easy to see where Professor Longhair fits into the history of the development of the music known as jazz. However, this overview by itself does not answer two important questions. One, was jazz born in New Orleans and two, was Longhair a jazz musician?

Professor Longhair, aka Fess

In the important film, Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together, Stevenson Palfi presents Longhair as a rhythm and blues pianist. More over, Longhair’s recordings are generally considered popular music rather than jazz, and are usually classified as New Orleans R&B. As for whether jazz was born in New Orleans, although no one indisputably knows, it is difficult to find definitive documentation that jazz was not a result of the great cultural confluence of influences known as New Orleans.

When asked was there a piano in his home and how did he learn to play piano, Longhair recalls that when he was coming up there were a lot of pianos around, some out on the streets and that he learned from his mother. In other words, yes, the music was all around him. But we must ask ourselves, is there any other place in the United States at that time period when pianos were found littered on the streets?

Longhair was a product of both his time and location: post reconstruction New Orleans. My two-cradle theory of jazz is simply that jazz developed out of the cultural context of turn of the century New Orleans where there were two major forms of music happening in the black community. One was the development of brass bands, a la Buddy Bolden. The other was the long line of piano kings a la Tony Jackson. A descendent of Tony Jackson via Jelly Roll, the “rowdy” (he had been a gambler and a boxer during his lifetime, “Whirlwind” was his pugilistic nickname) Professor Longhair’s distinctive piano stylings was a major moment/movement in the development of Black music in New Orleans.

In an important sense, in the beginning jazz actually was a two-cradle music. One cradle was piano music and the other cradle was brass band music. The typical New Orleans brass band included clarinets and a little later on, saxophones, as well as trumpets, trombones and tubas/sousaphones, plus, of course drummers. Typically, a brass band has two drummers; a snare drummer and a bass drummer. The tandem of percussionist often came up with tantalizing syncopations that no one man could achieve.

On the one hand, you might say that early jazz was primarily a piano professor tickling the ivories, or, on the other hand, early jazz could be a brass band, boisterously leading a procession of prancing revelers down a back street in old New Orleans. Either way, the resulting joyful noise, whether piano or brass band, was all good.