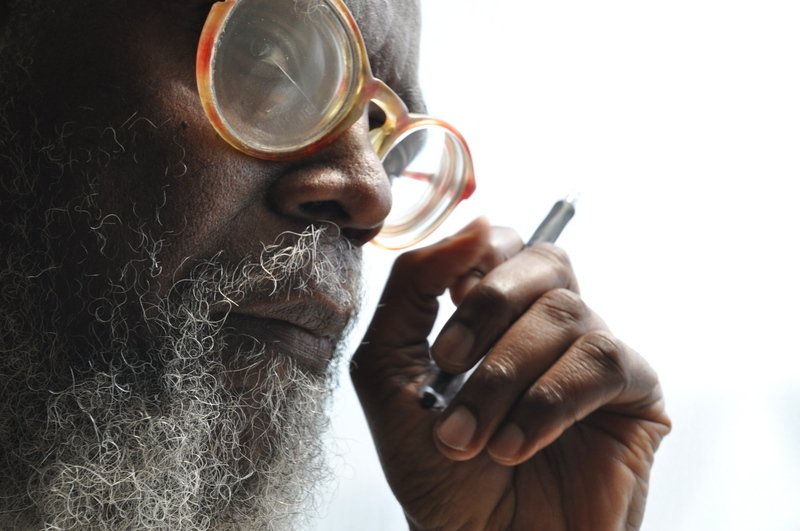

photo by Alex Lear

RAOUL’S SILVER SONG

Raoul stood on the wooden patio balcony enjoying the twilight’s slow departure. With the patient concentration of a piano tuner unhurriedly working in an empty ballroom, Raoul watched the evening shadow creep up the cream colored concrete wall as the sun light gradually dimmed and the criss-crossing sunbeam shafts merged into the darkest green of the shadow shrouded banana tree trunk.

With each slow breath, through nostrils that barely moved when he inhaled, Raoul caught the bouquet of courtyard odors: frying sausage from somebody’s pan, shrimp in the alley from last night, and the sweet subtle fragrance of watermelon waffling upward from the Johnsons just below him, sitting out eating the pink fleshed fruit and chatting about their grandchildren.

But more than what he saw or what he smelled, Raoul liked what he heard: the sounds of a New Orleans evening in the Treme area muted by the wood of old buildings, sounds mingling like the melodic strains of a brass band improvising, different elements going to the fore and then receding: a rancorous car horn blown at two kids chasing a ball into the street, the high squeal of the car’s brakes a cacophonous counterpoint to the car’s blasting horn; Mabel singing to herself while she cooked, today her natural alto was stuck on “Amazing Grace” sung in C; the Johnsons listening to their favorite Louis Jordan recordings; someone’s radio on loudly (the person was probably sitting on their front steps, with a beige touch-tone Princess telephone perched on the door sill, talking to a friend who was probably doing the same in her neighborhood), the station was WWOZ and the fifties R&B show had not too long ago come on; water and sewage moving through the plumbing — thick, heavy iron pipes which were common decades ago — that ran up the outside of the building next to the stairwell; a television barely heard, Raoul couldn’t tell what show it was or where it was coming from, but he could tell it was a television because every 35 or 40 seconds a burst of forced laughter erupted instantly and died down quickly; the long soft watermelon burp from below; and, the low eruption from his own bowels as Raoul passed gas.

What he liked about all these sounds is that no one sound was supreme, neither noise nor music was so loud or lasted so long that it dominated the soundscape — this was a good band.

Although the catalogue of sensual stimulants was long and varied, Raoul felt relaxed here. He savored the ballad tempo of day’s exit in this little courtyard. The atmosphere was soothing, it invited reflection, meditation, cat-napping, snoozing, quiet cigarette smoking, thinking things through, forgetting, reading letters over and over, a good long novel, memorizing a short poem. Everything. Nothing. Raoul liked this.

Raoul’s hand rested lightly on the heavy wood railing, a railing pitted by the bombardments of time, a railing no longer smooth like it was when initially, proudly, installed by the Heberts, a neighborhood family of laughing carpenters (a father, Harold, two sons, Francis and Eric, and a cousin, Daniel, whom everyone called “Two-Step”).

Whatever paint had once graced the railing was long since gone. Now the wood was colored by the pigments of natural aging: rain borne atmospheric dirt and rodent excrement, bird droppings and tiny insect slime; the bleaching of the merciless semi-tropic Crescent City summer sun; the seasoning of sweat and other body fluids; sundry dyes from a plethora of spilled drinks composed of every imaginable concoction of juices and flavorings used to disguise the sharp taste of the alcohol; colorings from an exhaustively long line of liniments, potions and medications (for example, a three-quarters full bottle of some chalky white substance of dubious medicinal value which had been pitched in real anger at the genitals of the third in a long series of tenants by a live-in lover on the way out — the bottle broke on the railing when the tenant successfully sidestepped the not unanticipated missile); the indelible blotches left by blood from a terrible accident with a knife which left a little hand permanently scarred; soot streaks from a holiday inspired outdoor barbecue that should never have been lit there in the first place; not to mention the many burns from snuffed cigarettes and the 159 ice pick holes assiduously bored into the wood by someone who was bored out of their skull one day waiting for a certain individual who never came.

None of this would have surprised Raoul. Like the patina of most elderly humans we meet whose skin tones reflect a full life, this railing had a long survival story. Raoul liked graceful survivors: people and things which held up well, didn’t cry or carp about life’s severities, but rather simply persisted in being what they were.

Raoul lived alone. He chose his lifestyle. He…

Someone was knocking at his door. He stood motionless. They knocked a second time. Raoul thought about not answering the door. A third knock. Louder. With the unhurried motion of a man who has enjoyed a long life and feels no pressure to accomplish anything else, Raoul moved slowly from the balcony into the front room and to the front door.

When Raoul opened the door a young girl stood there.

They looked at each other. She couldn’t have been more than 17 or 18.

“Raoul Martinez?”

“Good evening.”

“Excuse me. Good evening. Are you Mr. Raoul Martinez?”

“Who wants to know?”

“My name is Mavis Scott.”

“And?”

“And. I’m, uh, looking for Raoul Martinez.”

“What for?”

“Music lessons.”

“I don’t give music lessons.”

“………”

“I said I don’t give music lessons.”

“I know all your music.”

“What music?”

Mavis unhitched her large leather bag from her shoulder, lowered it gently to the floor, knelt beside it and quickly retrieved her flute case. She place the case on top of the bag, opened it, and assembled the flute, blew air through the silver cylinder to warm it, stood quickly and began “The Silver Song.”

“Well. Uh huh. I still don’t do lessons.”

Without hesitation Mavis started into “Ra-Owl.”

“Where you learn that from?”

“A record.”

“I ain’t got no record.”

“June Johnson — The Copenhagen Connection.”

“That was… How you got holt to that?”

“I like your music.”

“How you found me? How you know I was here?”

“I like your music.”

“I like a lot of stuff. That don’t mean I know everything.”

“But if you really like something, you learn about it.”

“Mavis…”

“Mavis Scott.”

“Alright. Come back tomorrow. Four-thirty.”

“You’ll teach me?”

“No, I’ll think about it. I’ll tell you my answer tomorrow.”

“You want me to call before I come?”

“Can’t call.”

“Oh they have phones at school.”

“Can’t call me. There ain’t no phone here.”

“Oh.”

“Good evening Miss Mavis Scott. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

***

“Come on in.”

When Mavis walked into Raoul’s room, she felt like she was falling into a past she had never seen but a past she wanted desperately to know about.

Raoul walked away from Mavis. He opened a half closed door and disappeared into the adjoining room.

An old armoir and an old piano dominated the room where Mavis stood. She looked for a television but there was none. She looked for anything that would give clues to Raoul’s personality, but there was nothing else personal in the room. The balcony doors were open to the courtyard and the window on the street side of the room was closed and tightly shuttered.

Raoul reentered the room, a trumpet in his hand.

Mavis looked at the piano. Raoul assumed she could play some piano. If she couldn’t at least play some chords on the piano it would be a waste of his time to try and teach her anything.

“Ok, hit some chords.”

He pointed toward the piano with his horn.

“Go head, girl. You say you wanna learn. This your first lesson.”

She sat at the stool, her hands just above the keys and then rested them lightly on the keys. She wanted to cry, unable to think of anything that seemed appropriate to play.

“Mavis, blues, b flat, watch me. Uh, uh, uh-uh-uh-uh.”

Mavis tried to think of blues chords, some notes, blues songs even. Every song she thought of she rejected because it was not the song he wanted. She didn’t know what he was going to play but whatever he was going to play she knew it wasn’t what she was trying to recall. With great effort she lifted her hands. It felt like some invisible force was trying to hold her hands down. Her hands dangled above the keys, coiled tightly, a leopard waiting to pounce but no prey passed her way.

Mavis bit her lip. Her nostrils itched and burned slightly. Tears formed on the inside edges of her left eye. He had already counted it out. Would it be too corny to play “CC Rider”? That was too simple. So was “St. James Infirmary” or even “Goin’ Down Slow.” But what key. B. Yes, he had said B.

Whenever Mavis was under pressure to perform her subconscious would flood her mind with so many possibilities that the hardest part of the creative process was not the thinking of something to play, but rather deciding on which one idea to play.

Once she had sat in at Jay-Jay’s place…

“Girl, you don’t know no blues? You don’t know no blues, how I’m gonna teach you to play jazz?”

Raoul walked out the room.

Mavis cried quietly to herself. When Raoul returned with a piece of paper in his hand he pretended he didn’t see her tears. Mavis quickly wiped her eyes with her forearm. Raoul sat the sheet of music on the piano stand. It was just a series of chords. No melody. No time signature. No bass lines. Just chords.

Raoul snapped out a slow walking tempo.

“Uh. Uh. Uh. Uh.”

Mavis smiled when she heard Raoul’s trumpet. This was “Ra-Sing.” She hadn’t recognized the changes written out on paper, but she knew the song. By the time they were at the tune’s bridge, Mavis was very comfortable with the chords. If she were playing flute there is so much more she could have done, but on the piano all she could do was feed chords.

Suddenly he gave it to her.

Mavis was ready. She did a break and filled the hesitation with three deftly timed, chimming block chords. Then started a phrase that consisted of four chords which resolved on the next chord in the progression. At the bridge she dropped the tempo compeletely and strung out a set of altered chords which she had thought of two years ago while listening to the record over and over. Mavis was ready.

“Go on, go on, girl.”

“I could play it better on flute. I don’t have much piano chops.”

“OK. Do it”

Mavis picked up her flute case from beside the piano stool, assembled her flute, held it to her lips and waited for Raoul’s count.

Raoul closed his eyes. The only count was an almost imperceptible nodding of his head. But Mavis saw, she saw and was ready. He would see. She was ready.

They played “Ra-Sing.” At the bridge he dropped out and Mavis confidently flew.

“Play it pretty baby, play the pretty way you talk.”

They played the song through twice.

“Yea. Now that’s better. Where you from girl?”

“Right here.”

“Yea, huh.”

“Yes,” she smiled, resting her hands and her flute in her lap, allowing her head to tilt a bit to one side. “Same place you from. We both coming from the same place.”

“Yeah,” he said with a slightly mocking “we’ll see about that” tone. “Let’s take it from the git go. Watch me now.”

They chased each other playing a fleet “Ra-Owl”. He laughed at her swirling trills.

“Don’t put no dress on this man now.”

“No, just a pretty shirt,” and she did it again.

It was uncanny the way this young girl played something like June did. At the bridge June had always hung back, quarter noting just behind the beat. She was playing it like June played it. They ended together, Mavis voiced below Raoul.

“Solid.” He smiled. There was nothing like playing. Raoul thought about playing with June. Mavis was still laughing. “Yaknow, June always used to say,” Raoul altered his voice to imitate June’s famous growl, “mannn, ya don’t play music. You serious music.”

Mavis stopped laughing. She didn’t stop smiling. She looked at Raoul.

“Girl, music is more than just a love, it’s a passion and that’s the way you got to play. It’s got to be like you can’t help yourself.”

“You mean you got to give yourself to it.”

“No, baby. I mean you got to get everything you need to live from it. Fish need water. Birds need air. You got to need music. Yaknow, you got to need it bad, so bad that when you don’t play, you can’t live.”

There was still so much Mavis did not know about herself, especially about what she needed to feel fully alive.

Raoul wasn’t looking at her. He started to play. His horn was at his lips. He fingered the valves quickly. His cheeks puffed out. He almost started but didn’t. Raoul thought of something. Mavis didn’t know what he was thinking but she could tell he was thinking of something.

Raoul didn’t know why he thought so suddenly of Martin Luther King getting shot in the neck, except that really living was the only thing worth dying for. Living the way you wanted, doing what you wanted to do, that’s all was worth dying for. Raoul played “The Silver Song.”

Mavis joined him. They played forty-six and one half choruses when Raoul just stopped suddenly. He put his horn down. Stood up. Walked out the room. The lesson was over. It was almost night. Mavis packed her flute quietly and sat for a minute looking at Raoul’s horn. She fingered the top of her flute case like it was a piano, she was fingering the changes to Raoul’s “Silver Song.”

She played the piano well, so well that her piano teacher encouraged her to become a piano major. He said she had the passion to play like he had never seen in a student in a long time. When Antonio Luzzio said that, Mavis wondered what did he know about her passions. All he could teach her was technique, she remembered thinking when Mr. Luzzio spoke softly about piano and her passion. Later, Antonio Luzzio said to her one day when she was playing Chopin for him: “Your hands love the piano and the keys love them back. I will teach you the technique so you can forget the technique.”

Now, studying with Raoul, Mavis blushed to herself. She never thought she would be so thankful for what Mr. Antonio Luzzio had taught her. He had taught her to play correctly, so now there was nothing between her and the music. She could hear the changes and hit the right chords. She could also alter the changes and create new chords that were harmonically correct. “Thank you Mr. Luzzio,” Mavis said to herself.

Raoul finally came back into the room. He was getting his soft leather cap out of the almost antique armoire. She had seen cedar robes before, with the long dressing mirrors and the strong but pleasant wood smell.

“I can’t come tomorrow,” she said as she watched him methodically place the black cap on his head. The cap looked expensive. Mavis did not know that the cap was from Norway, nor did she know it was a gift which Raoul cherished.

Her saying she couldn’t come tomorrow reminded him to tell her she couldn’t come on Friday; she didn’t need to know why.

“Neither next day, either. Look here, for next time, work us out a ‘rangement for “A-Train” in slow to mid tempo. You better mute me too.”

“Why?”

“Why? ‘Cause I said so.”

“No, not the lesson, I understand that. I mean why I can’t come on Friday.”

“I done already tolt you, ’cause I said so.”

“OK, Raoul,” God, she hoped she had said his name casually enough, “because you said so.”

He didn’t answer. He left the room. The lesson was over.

***

They were playing Monk — rather Raoul was playing Monk and she was struggling to find something to play. Everything she thought to play was so obviously not what should be played.

“Why is Monk’s music so hard to play?”

“It ain’t hard to play. It’s hard to fake!”

Mavis chuckled almost inaudibly, agreeing with Raoul’s pithy summary. Raoul played a half chorus and stopped.

“Monk made you play or else sound like you couldn’t play.”

Silence.

“Like the hardest thing about Monk is rhythm, and that’s the hardest thing in life, to find your own rhythm.”

“But when you playing with others you can’t just play your own rhythm.”

“The trick baby is to know when to solo, when to ensemble, when to comp and when to lay out. That’s life. That’s music. Sometimes you take the lead with a solo, sometimes you play your part right long side everybody, sometimes you’re in the background accompanying what’s going on, sometimes you don’t play. Dig?”

“But how do you ensemble when everybody else is playing a way you don’t want to play?”

Raoul turned to the piano and played the head of “Evidence” again. He picked up his horn and played variations on the theme. He got up off the piano stool and kept playing, motioning for Mavis to sit at the piano. Mavis put her flute on top the piano, sat and comped the changes. He stopped. She stopped.

“When you can’t play, lay out.” He played some more. She joined him. He stopped. She started to go on. She stopped.

“Some fools think shedding is about perfection, yaknow that ‘practice makes perfect’ bullshit, but, yaknow, that ain’t where its at. Shedding is for learning what not to play, learning what doesn’t work and learning not to do that. I mean your woodshed ought to be full-a all your mistakes. Practice making mistakes. Playing makes perfect. Shedding is all about making mistakes, baby.” He started again. He stopped. She started to play something. It didn’t work. She stopped.

“When you can play what you can’t play now, then you can play.” Raoul started again. Before she could start, he stopped. “Yaknow, it ain’t about you. Monk was about Monk. But when you play Monk, you got to be you playing Monk. When you play your stuff then its about you.” Raoul played “Evidence” again. Mavis comped. Raoul soloed. He altered the changes. Mavis followed laughing. Raoul’s logic was so clear. He returned to the head. They ended together with a flourish, she had the sustain pedal down and the piano’s resonance undergirded the mirth of their entwined laughters.

“Mavis. Blues. B flat. Use the flute. Uh. Uh. Uh-uh-uh-uh.” And they were flying. She had a variation of “Killer Joe” that was smoking and matched perfectly what he was doing. Soon she found that she was leading the song. At the bridge she stomped her foot loudly on the floor, indicating a stop-time. She ripped off four measures and threw it at him. He was pleased with her self-confidence and began trading fours with her. She started flutter tonguing and screaming false notes. He wah-wah muted the horn with his hand. She hummed into her horn. He picked up a metal ash tray and got right nasty.

This was something like that night in Jay-Jay’s when she had sat in but it was better because it was just happening, and she was not having to prove anything. Mavis remembered something she had played that night, it was something she had heard Rahsaan do on a record and she had copied it. When she did it that night, the crowd loved it. When it was her turn, she did that same thing.

Raoul stopped.

“Nah, why you played that. That shit don’t fit. It ain’t you, is it?”

“What do you mean it’s not me.”

“Who you heard do that?”

She started to deny that she had heard anyone do that. They were having so much fun playing. It had felt so good to be playing on an equal basis with him.

“Rahsaan.”

“Who?”

“Rahsaan Roland Kirk on the alb…”

“Rahsaan can play Rahsaan. You play you and when you ready to play Rahsaan then you be you playing Rahsaan but don’t be taking Rahsaan shit trying to make it yo shit. You don’t know what all that man went through to get that sound. You don’t know what he was thinking. And I don’t want to know what you thought he was thinking or feeling. I wants to hear what you thinking and what you feeling, even when you playing his shit. Play me some Mavis Scott. I wants to hear Rahsaan, I’ll put a record on.”

“I just, I just thought it would fit there.”

“Imitation don’t never fit in jazz. Don’t care how much some people might think they like it. Jazz is for real and if you ain’t being for real, you ain’t playing jazz.”

Raoul walked out the room. Lesson was over.

Just as Mavis was about to leave, her flute packed and her feelings shredded like a tom cat’s favorite scratching pole, Raoul returned into the room with a picture in his hand. He held it out to her.

Mavis looked at it quickly.

“That’s me and June in Copenhagen.”

“Um humm.” Mavis barely held the metal frame a full minute before gently returning Raoul’s most treasured photograph.

“I thought you might like to see it, you know, you knowing all about me and June and such.”

Raoul had no way of knowing that Mavis saw his picture everyday. How could he know that Mavis had her own copy, sent to her mother by June who was her second cousin. Raoul knew everything but he didn’t know this. He thought Mavis was hurt because of what he had said to her, why else didn’t she look at the photograph which he had seldom shown to anyone.

“Thanks.” They stood uncomfortable in the silence like musicians listening to the playback of a sad take late in a recording session that has not gone well — even though they had tried their best, the outcome did not sound too good. Maybe the best thing was just to pack it up and try again on another day.

***

After knocking twice and getting no reply, Mavis tried the door knob. The door was unlocked. She let herself in, moved quickly to the piano, and set up to shed — it was no longer like basic lessons, now they spent most of the time practicing together.

The way they played together was almost like they were equals — well not really equals, because Mavis was only a beginner, but they played together like colleagues, musical colleages. No, it was more than that, there communion felt to her like more than band mates who only played periodic gigs together and seldom saw each other beyond that. Well, although it was true these sessions were the only time they saw each other, still it was more than just sessions.

The way they would break out laughing simultaneously after playing a good exchange or after hitting an unplanned ending abruptly but precisely in tune with each other, that was like friends. That’s what it felt like, good friends.

After all, Raoul didn’t play in public anymore. Absolutely refused. So, in a sense, Mavis was Raoul’s only peer. “Don’t nobody want to hear no old man playing no more.”

“You ain’t old.”

“You too young to know what old is.”

But there was also something else simmering between them. Something just beneath the surface. At least, Mavis wanted there to be something else. Well, at least, sometimes she wanted there to be something else. She wasn’t sure if he wanted there to be something else. He had never even so much as touched her before. Well he had touched her shoulder once and had nudged her with his hip to catch a beat or something, but his bare hand had never touched her skin.

Where was he?

Mavis played her flute for a minute or so, waited. Raoul did not appear.

Another Raoul-less minute passed slowly.

“Raoul.”

Nothing.

Mavis looked at the bedroom door, or rather looked at the door she supposed led to Raoul’s bedroom. She had never gone any further into Raoul’s apartment than the front room where they shedded or quickly dashing in and out of the little bathroom on a couple of occasions.

Should she go inside the bedroom?

She went to the door.

Should she knock?

The door was already ajar.

“Raoul,” she called out.

Nothing.

She touched the door.

Should she push the door open?

She opened the door.

Raoul lay sleeping on his bed. Naked to his waist, or maybe he was totally naked and only exposed to his waist; a spread covered the lower half of his body. Mavis could not tell if he had any other clothes on.

She trembled.

Should she?

She started to call his name.

Should she wake him?

Or, should she… ?

She undressed quietly, quickly. Maybe, if she just climbed into his bed. The window was open. A breeze blew through. Maybe, he wasn’t really asleep. Maybe, he was waiting to see what Mavis was going to do. What was she going to do?

Mavis felt the wind dashing slyly between her legs, mocking her quandry, challenging her to move from the spot where she stood glued in confused frustration.

The wind blew again. She felt a chill there.

The curtain moved.

Mavis turned her head to look at the curtain. Is this what Lot’s wife felt like, unable to go and unable to stay? Mavis’ head hurt. Why was she even thinking about the bible and where did Lot’s wife come from? Something moved.

Raoul had moved, turned half way over toward her.

No.

Raoul snored. It was a soft snore, but a snore. Would he wake up before she could get out of the room?

Carefully, slowly, Mavis bent to retrieve her clothing which lay in a shameful little pile beside her. This man was older than her father. Almost old enough to be her grandfather. Mavis did not understand the attraction, nor the repulsion, but she felt both, and, after initially acting on the former, was now being swayed by the latter.

The curtain moved again.

Mavis held her breath.

God, this was stupid.

With clothes in hand, Mavis stood trying to figure what was the better choice, try to dress quickly and silently in here, or slip naked back into the front room and dress in there. Suppose Raoul woke up while she was dressing? Suppose when she moved to go into the front room the floor squeaked or the door squealed and Raoul saw her naked?

How could she explain this to Raoul?

Raoul moved again, rolled away from the door.

Mavis dashed quickly into the front room. It took her so long to get dressed. Her hand trembled terribly.

Once dressed, she picked up her flute — the metal felt so cold — and stood silently in the middle of the floor. What now?

Eventually, she decided to leave.

At the front door she wondered whether Raoul was alright.

Mavis opened the door and closed it softly behind her and started to walk away. But suppose he were sick. He hadn’t looked sick or anything. He looked alright. But maybe he had a heart attack. But she was sure he had been breathing normally. At least she hoped he had. Mavis didn’t remember his snoring because she herself had not been breathing normally. If something were wrong and she left him like that; she couldn’t do that.

Mavis went back into the apartment. Everything sounded ok.

Mavis walked across the room. She didn’t hear anything that sounded wrong.

Mavis stood in the bedroom door. Raoul slept soundly, except he had turned toward the door and lay fully exposed. Mavis saw him facing her nude. She trembled anew. Finally she left.

***

“Hey girl what happened to you yesterday. I fell asleep about two and didn’t get up til six. Did you come and think I wasn’t home or something?”

“No. No. I didn’t, couldn’t come yesterday. I just came by today to pay you what I owe you because I won’t be able to come anymore.” Why had she lied? She wanted to call it back, but didn’t.

“You don’t owe me nothing. I just want to hear you when ever you start playing if you do like you say you gon do and if you keep playing like you been playing.”

“Yes, when I really start playing I’ll let you know and if you play, you have to let me know.”

“I won’t, but then, one never knows, do one?”

“No, for sure, one never knows until one does.”

“Yeah you right, girl. Until one does, one don’t.”

Mavis stood up, “Raoul, thanks for your help.” Her hand was sticking out toward him. He took her hand into the warmth of both of his and held it. He looked her in the eyes.

“Mavis, you pass it on whatever it is you think you learned funny girl.”

“For sure. Always learn. Always teach. And always know when you suppose to be learning and when you suppose to be teaching.”

He was still holding her hand. “Lady, you got it.” He slowly returned her hand to her.

Everything felt so final, like this was graduation and even if they saw each other again it would be different. Maybe that’s what calling her “lady” meant.

“Do you still, I mean are you still tied up on Fridays?”

“What made you ask that?”

She walked toward the door away from him, “Oh youth I guess.”

“You’ll get over it.”

“Yes, well…”

“Goodbye sweet lady, play what you must but always be ser…”

“….always be serious about the music.”

Raoul kissed her on her nose. She turned quickly, nearly stumbling as she ran hurriedly down the stairs onto the waiting sidewalk below. She heard a radio. She heard a tv. She heard some kids playing. Cars passing. Somebody arguing about something. A riverboat whistle blowing on the river. The St. Claude bus pulling off three blocks away. And quietly above it all, Mavis heard Raoul’s “Silver Song.” At first she thought the sound was in her head. Then she looked up.

Raoul was sitting by his front room window, playing with his horn stuck out the window, playing for the whole neighborhood to hear.

A new found confidence squared Mavis’ shoulders as she loped down the street humming along with Raoul’s trumpet.

—kalamu ya salaam