JANUARY 25, 2018

Keeping the Poor

Poor

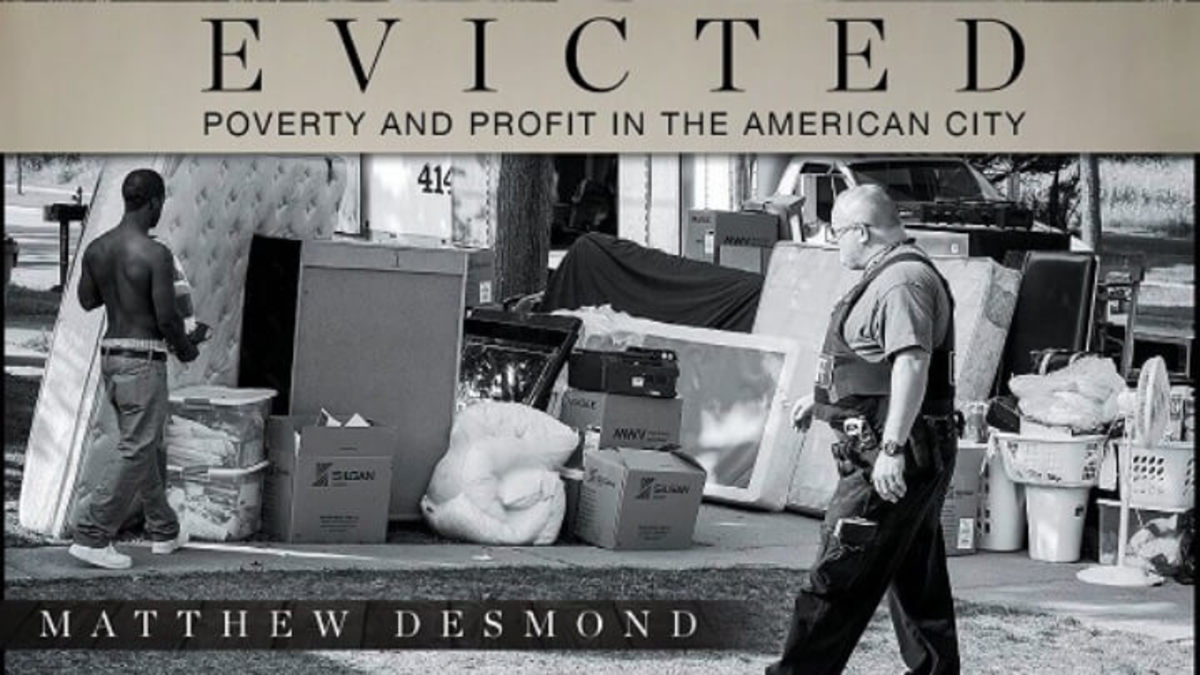

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, by Matthew Desmond

Why is it that many, if not most poor people in our society seem trapped in misery? Matthew Desmond gives us part of an answer in this well-executed ethnography of two populations of poor people, one black, one white, in Milwaukee.

Desmond, a Harvard sociologist, used his MacArthur Foundation “Genius” grant to support about three years of work, living first in a largely white trailer park in southside Milwaukee, then in a largely black inner city area of the northside. Telling people he was a writer who wanted to write about their lives, he gained the confidence of maybe a dozen people in both places who are pseudonymously featured in the book. His subjects included a prominent landlord on the northside, and the property manager in the southside trailer park.

For starters, not one of the subjects has a steady job. All rely on some combination of income not related to a regular job. This could be food stamps, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security, disability payments, or hustling on the informal economy through dealing drugs, casual, off-the-books work, or prostitution. For these people, rent constitutes typically two-thirds or more of monthly income.

Many of them have children, and that poses extra challenges when living in poverty. Having children imposes higher standards that one must meet in order to keep them. At the same time children are more likely to damage apartments or bother neighbors; either outcome raises the risk of giving the landlord a reason to evict a tenant. You can obviously be evicted for failure to pay your rent, AND in addition, for your children being children.

Rents in poor areas are, paradoxically, high, because the poor population are largely captives: they are prevented by means legal and illegal from moving out.

Rents in poor areas are, paradoxically, high, because the poor population are largely captives: they are prevented by means legal and illegal from moving out. Middle class neighborhoods and suburbs don’t want them, and laws against discrimination have been ineffective. This especially affects nonwhites, of course, but even poor whites are largely kept confined to the areas where they already live.

One of the strengths of this book is that it also lets us look at things from the landlord’s perspective. Landlords do make a lot of money and live well—and well away from their tenants. But they also have a constant challenge to keep their properties from deteriorating when occupied by people who have no resources for upkeep, few skills, too many people in an apartment (usually without the landlord’s permission) and constant impingement of chaos from the inner-city streets (e.g., drug dealing, violence, homelessness).

As a result, the landlord resorts to eviction frequently. At any given time a significant part of the population is either on notice of imminent eviction, or literally homeless after an eviction. Getting adequate housing after an eviction is even more difficult because the eviction is on the public record. That’s one more way of locking people into bad inner city housing.

Conservatives often argue that people are poor because of poor choices they have made. This book makes clear how simplistic that is, but it also shows us that people frequently do make bad choices, like withholding rent because the landlord hasn’t made repairs, or getting back together with an abusive spouse, or spending scarce funds on impulsive purchases, or repeatedly relapsing into drugs or alcohol. The bad choices don’t make people poor, but they do help keep them poor.

Desmond argues that what makes them poor is a society that is increasingly unequal and that systematically fails to provide people with what they would need to escape poverty. That would include not only an adequate income, but also good schools, good health care, and stable, decent housing. He believes we have the resources to deal successfully with this problem, as other advanced Western societies have done, but we lack the political will.

He concludes with a thoughtful appendix that discusses his ethnographic methods, and how he used other methods, such as survey research, to fill in the gaps.

Reading Evicted is as absorbing as watching a slow-motion video of a train derailment. We need to get back on track.