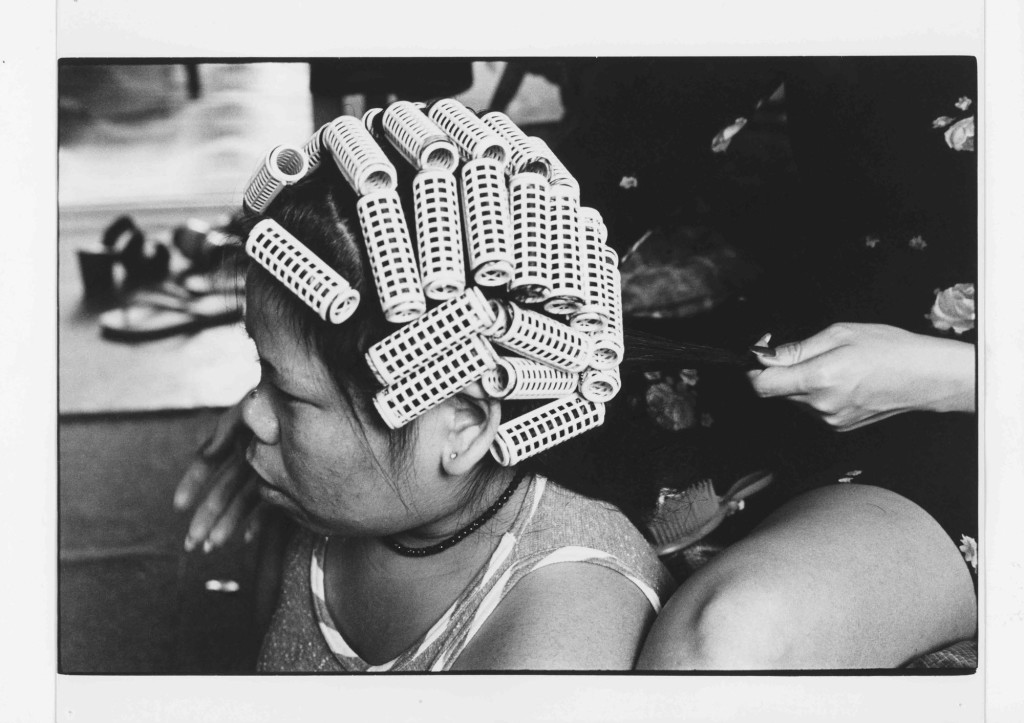

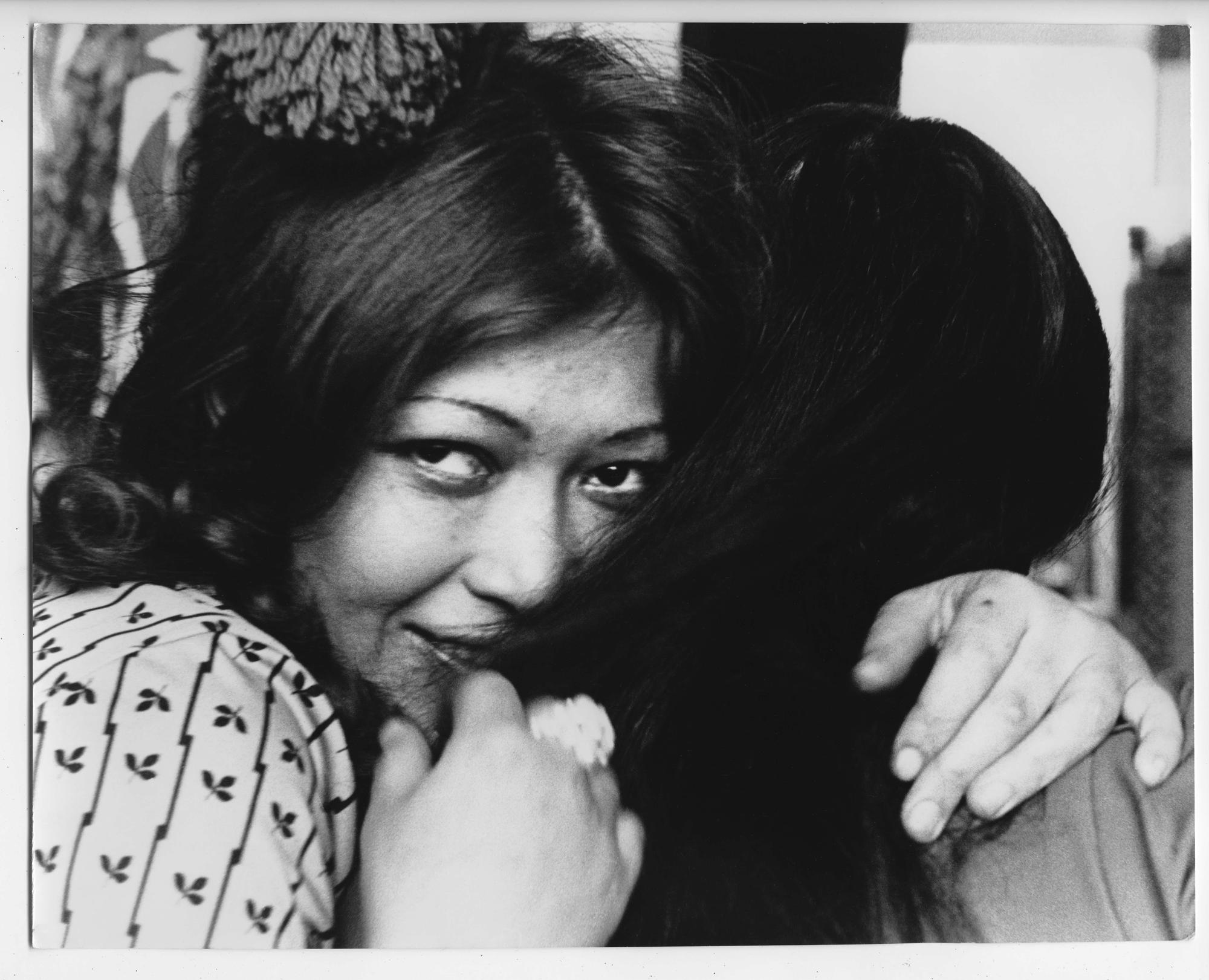

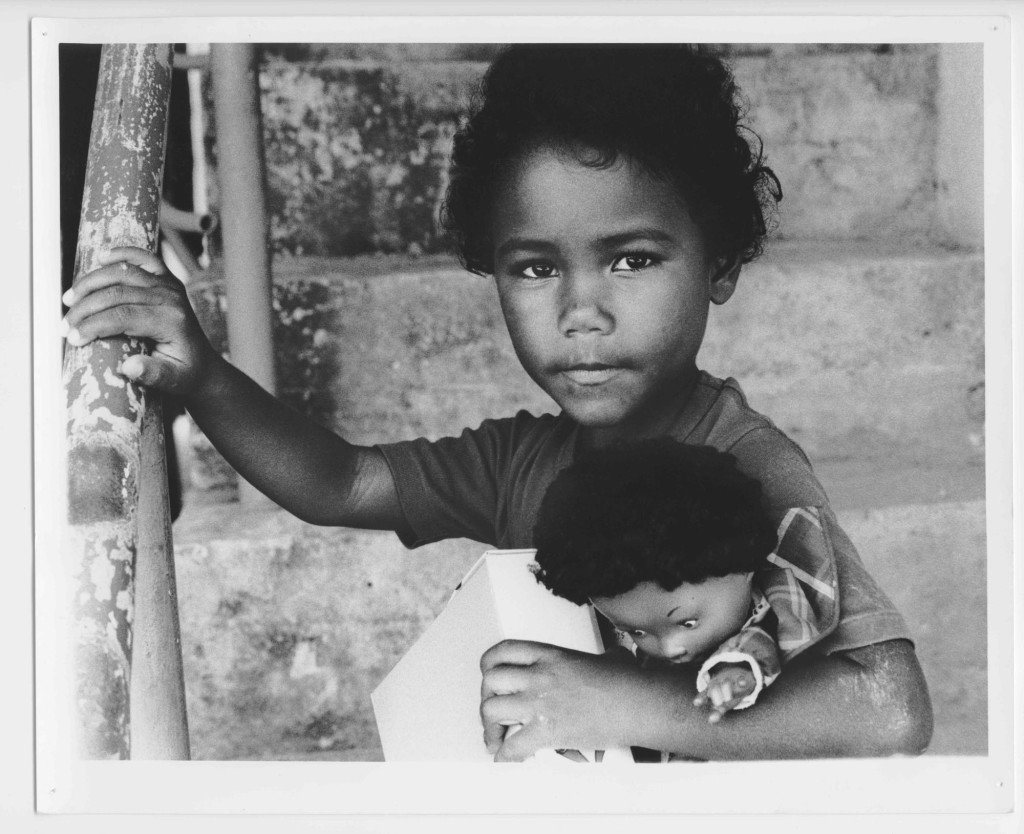

mao ishikawa’s

stunning photographs

of her friends

in 70s okinawa

The cult Japanese photographer gives

her first-ever English language interview,

about her new book

‘Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa.’

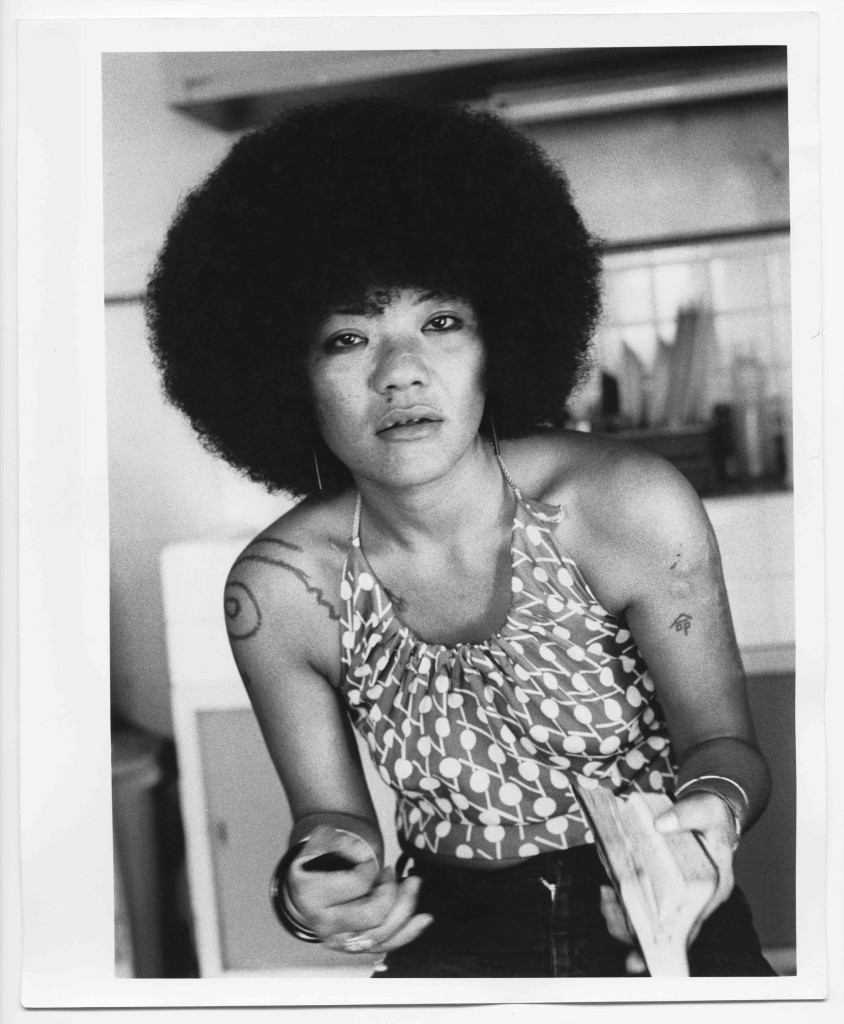

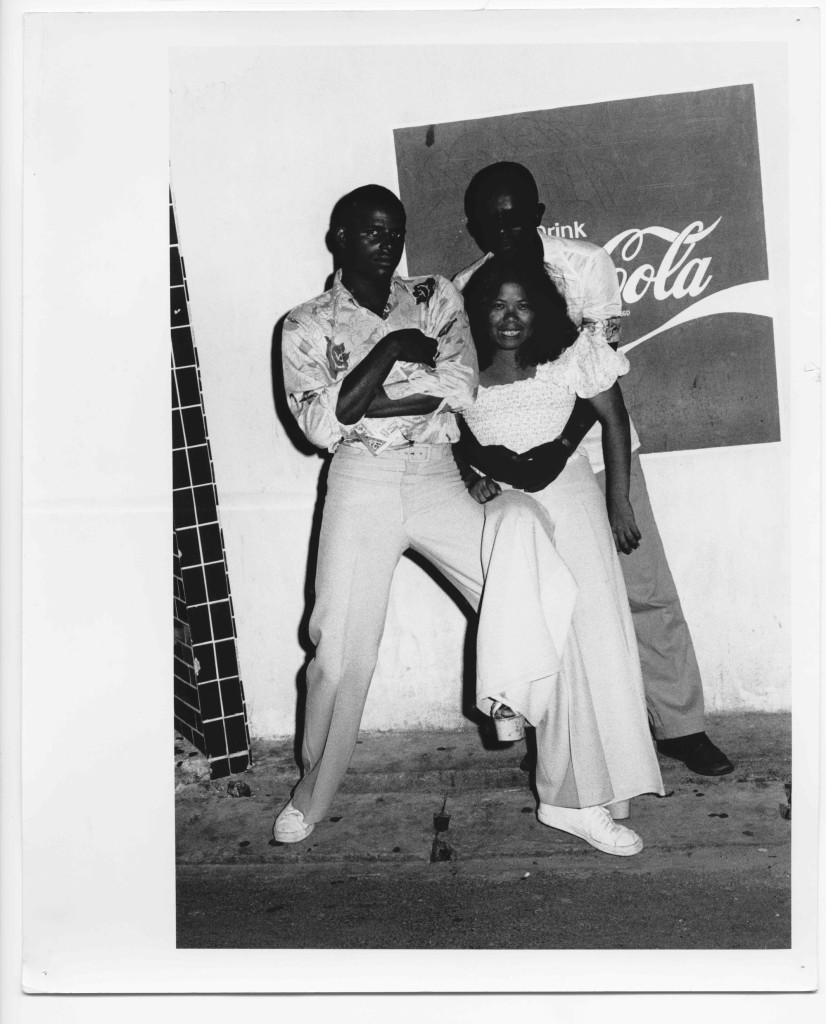

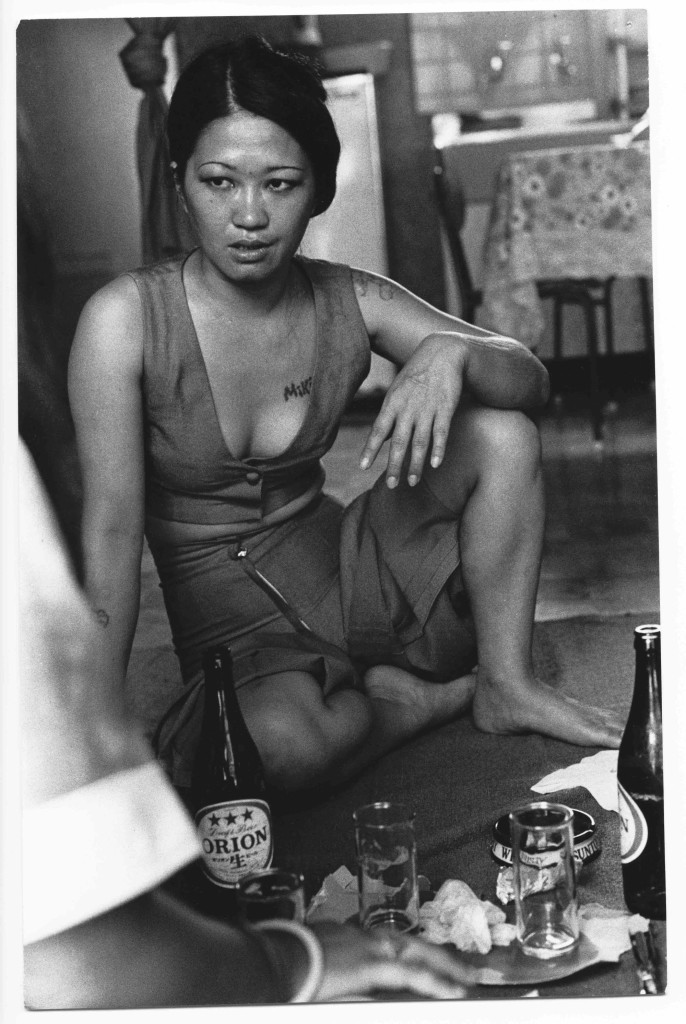

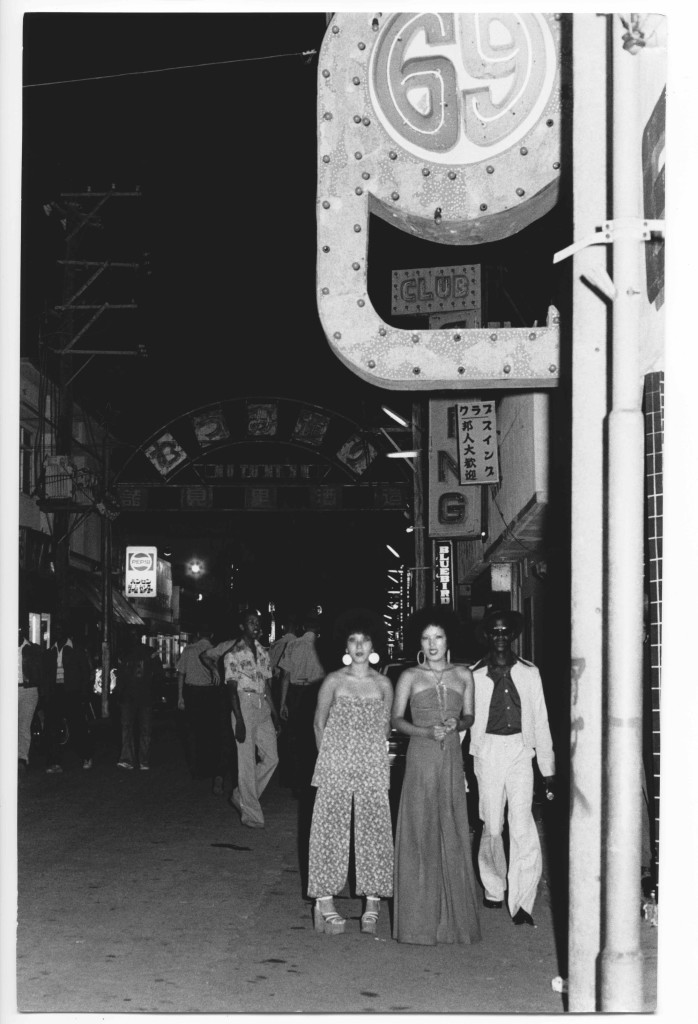

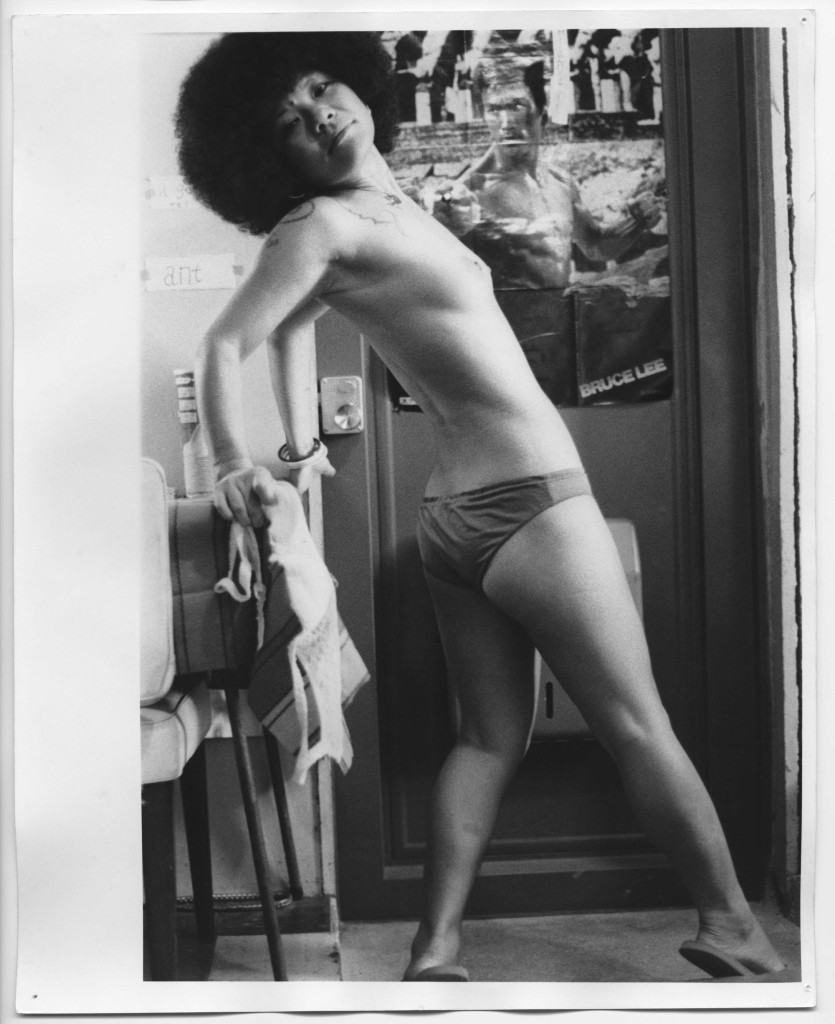

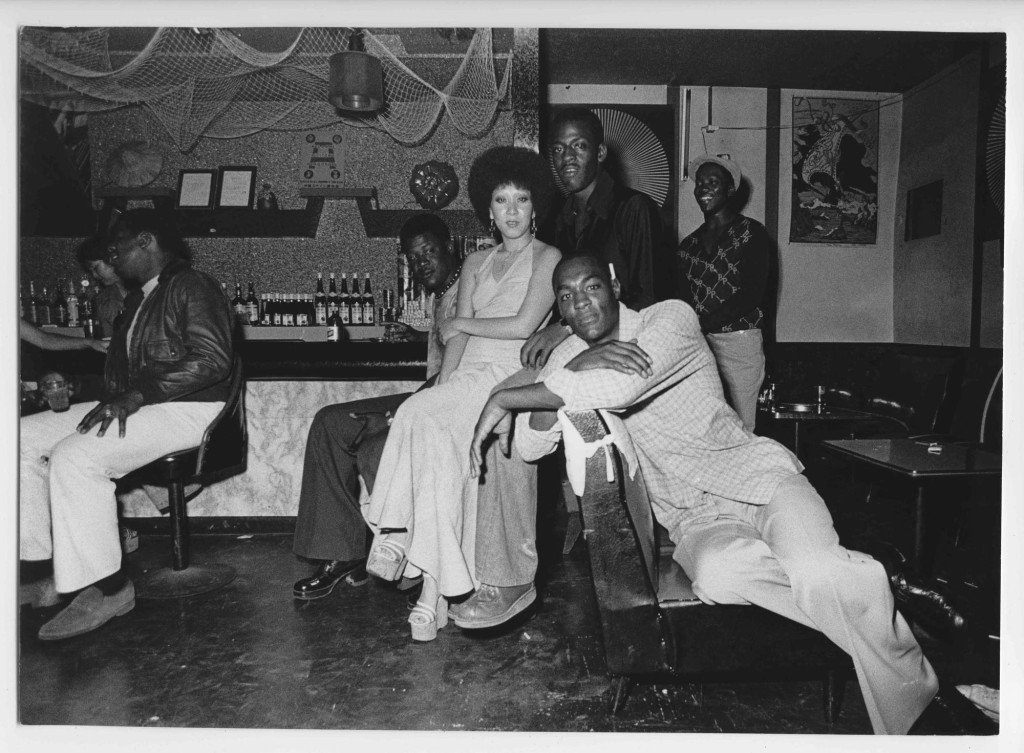

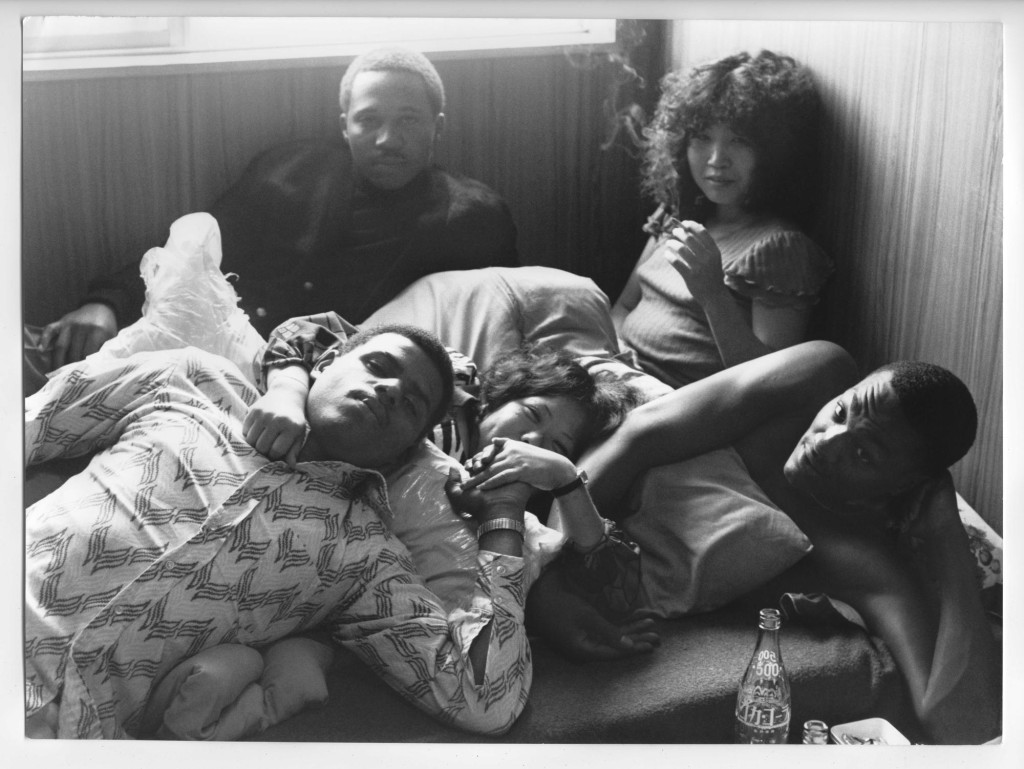

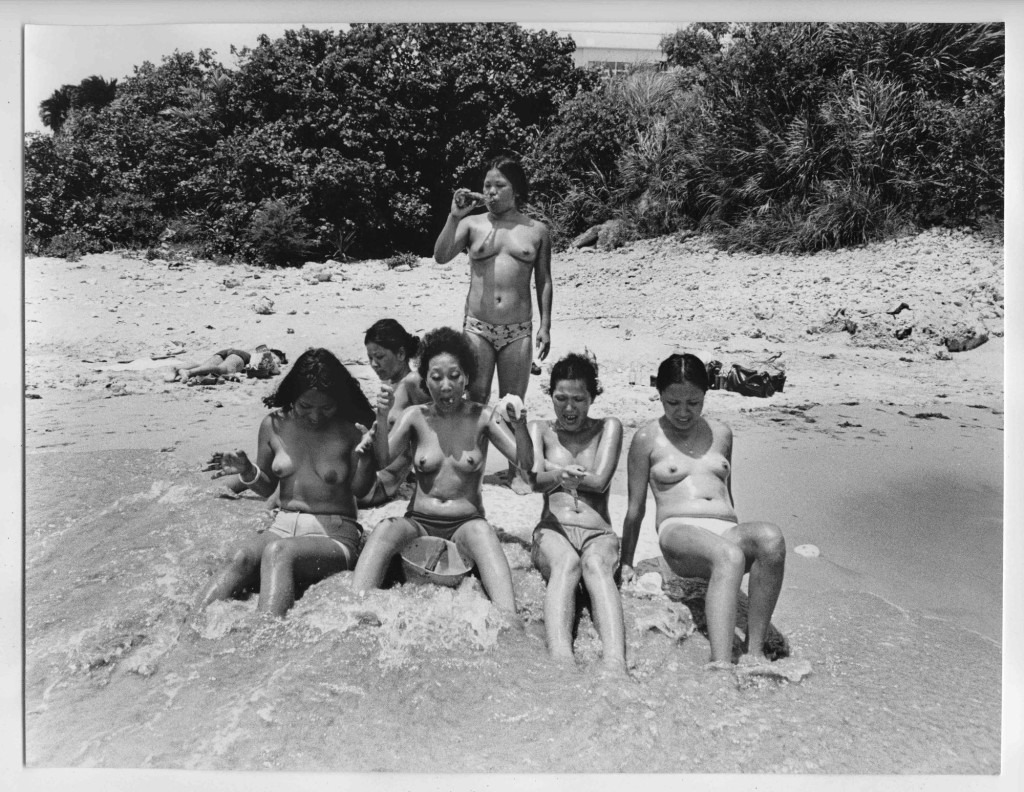

This Tuesday, at New York’s subterranean photobook shop Dashwood, cult Japanese photographer Mao Ishikawa is signing her first monograph to be published in the United States: Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa. The newly released silkscreen book features striking black-and-white photographs of Mao and her girl friends, who worked in segregated GI bars, along with their boyfriends – the black army soldiers who frequented those bars in American-occupied Okinawa from 1975 to 1977. The images of carefree 20-year-olds as they laugh and cry, drink and fall in love, contrast sharply with the divisive tensions of the militarily controlled island.

After just a few months in photography school — where she was taught by renowned photographer Shômei Tômatsu (who later championed her work) — Mao dropped out and returned to her home in Okinawa to begin her first project. “At the time I was young and rash, and before I gave it any thought I was already doing it,” recalls Ishikawa. “I couldn’t speak English at all but I went and talked to a proprietor of one of the bars and started working there that night. The customers were almost all U.S. soldiers in their 20s. Being around their age I was very popular. I had boyfriend after boyfriend. Sometimes one would rent an apartment and we would live together.” Here, Mao recounts her experiences for the first time to an English audience.

What was it like growing up in American-occupied Okinawa?

I was born eight years after the end of the war. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Okinawa was cut off from Japan and placed under occupation by the U.S. military. Until the “Reversion to Japan” in 1972, Okinawan police had no authority to arrest U.S. soldiers who were involved in accidents or crimes against Okinawans, so even when caught, suspects were handed over to U.S. military police and tried in their courts. Whether they ran over Okinawans with their cars, or raped women, robbed or killed, and even if they received a sentence of several years, there was no way for Okinawans to know whether or not those sentences were actually carried out. It was said that most of them were sent back to the U.S. and never actually went to prison. In that time it was like a U.S. colony where troops could do whatever they wanted. That is when I began to question: Is Okinawa really Japan? Are Okinawans really Japanese? I think that many children of that time period grew up asking the same questions.

Tell me about segregation at the time.

The Civil Rights Movement that started in America had spread among the U.S. troops. In April 1975, the year I began working in a black bar, the U.S. had completely withdrawn from the Vietnam War. I have heard that black soldiers were stationed on the front lines in Vietnam and that there was discrimination within the troops. Black soldiers and white soldiers wore the same uniforms and worked together, but once they changed into their civilian clothes and went out into town, there was trouble and endless fights. I have heard that that is why the entertainment districts for U.S. troops were segregated into white and black districts. However, I don’t really know if that is true.

Why did you and your friends choose to work at black-only establishments?

When I decided to take pictures of U.S. soldiers, I had never been to one of those entertainment districts, so I asked a journalist acquaintance what bar would be good and they told me of one in the black district of Koza city. I did not consciously choose black over white.

The Okinawan women other than me said that they started to come to the bar because their friend worked there, and then fell in love with a black soldier that they met there, and eventually ended up working at the bar. Women from mainland Japan liked black music from when they were little, found a lover at a club that black soldiers frequented, followed them to Okinawa when they were deployed and lived there. They broke up with their boyfriends but would stay in Okinawa and work at a black bar. There were many such cases.

What was it about your girl friends that was so interesting to photograph?

Okinawa is a small island. Because everyone knows everyone, many people live their lives concerned with how others see them. At the time when I was photographing, many Okinawans had the impression that black people are good at dancing, good at sex, and poor. In that milieu, these women fell in love with black soldiers that they met at the bar without any concern for how the world saw them. “What’s wrong with loving black people? What’s wrong with working at a bar? What’s wrong with enjoying sex?” they asked, and lived their lives freely and openly. Those women were very cool. I was more and more impressed as I photographed them. And a part of me was in them as well. Because I too worked at a bar, and lived with a black soldier that I met there and loved him.

What did you learn from the Americans?

American soldiers were very cheerful and self-assured to the point of arrogance. They didn’t care about how others saw them; they said and did whatever they wanted to. I think that that is very good compared to the Japanese who try to conform to society. They were closer to my personality and so it was very easy to live with U.S. soldiers.

Okinawa, which used to be the independent Ryukyu kingdom, was annexed by force in 1879 by Japan. The Japanese stated that “Ryukyu is over. Now this is Okinawa prefecture,” and the Ryukyu kingdom which had lasted for 500 years was dismantled and made part of Japan. That history, the relations between Okinawans and the Japanese, the history of black people and their relations with white people; I think they are very similar. I think that sympathy is a big reason I liked black people more and more.

What was it like when they left?

While I was living in town, I had three boyfriends, but it was different for all of them. Two of them proposed to me but I did not love them enough to marry them. The last man I loved, and when I discovered that he actually had a wife and child in America, I felt tricked and angry, but after a while, since I already loved him, I lived with him until he went back. The day he went back to America, I was so sad and lonely. He treated me kindly but his heart had already flown back to America. So I decided to give up and saw him off relatively calmly.

You initially published the book Hot Days in Camp Hansen, comprised of some of these photographs, back in 1982. What was the general response to the book?

At the time, the book was sold by mail order and so I did not have the opportunity to hear people’s thoughts on it. However, a woman who lived in Tokyo and bought the book said that it had moved her so much that she came to Okinawa to meet me.

How was your work received in what was then a very male-dominated industry?

At the time I had almost no interaction with the people in the photography industry of mainland Japan so I don’t know. The book was published by a group of Okinawan photographers who had started their own publishing company, but other than me all of them were men. They praised my photographs a lot because “these are photographs that couldn’t be taken by us men!”

Tell me about Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa and the images being published for the first time?

Miwa Susuda, of Session Press publishing house and Dashwood Books, came all the way from America to my home in Okinawa. I showed her my photographs and she said “beautiful!” many times as she looked at each one politely. I had never seen someone who would say that out loud so straightforwardly; her reaction moved me. This woman really understands my photographs. I was very happy. Afterwards, I sent all of the photographs to her, and left everything up to her, as I had faith that Miwa would create a good photobook. However, I did ask her to name the book Red Flower. In Okinawa, we call the deep red flowers that bloom everywhere akabana. Their image matched that of the women: flashy, free, and strong at the core. I also asked for the cover to be that deep red.

Miwa sent me a bare-bones sample book, but it wasn’t a completed version, so I haven’t yet seen all of the photographs that are to be published in America. I don’t know what unpublished photographs are included. I like all of the photographs I took, so it doesn’t matter to me which she has chosen. All of them are photographs of those women and their way of living that I was attracted to. I am very excited to see the book at the signing this month.

The book signing for Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa will take place on March 28 at Dashwood Books from 6-8pm.

Translation Jun Sato

All images courtesy of Mao Ishikawa and Session Press

>via: https://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/mao-ishikawas-stunning-photographs-of-her-friends-in-70s-okinawa