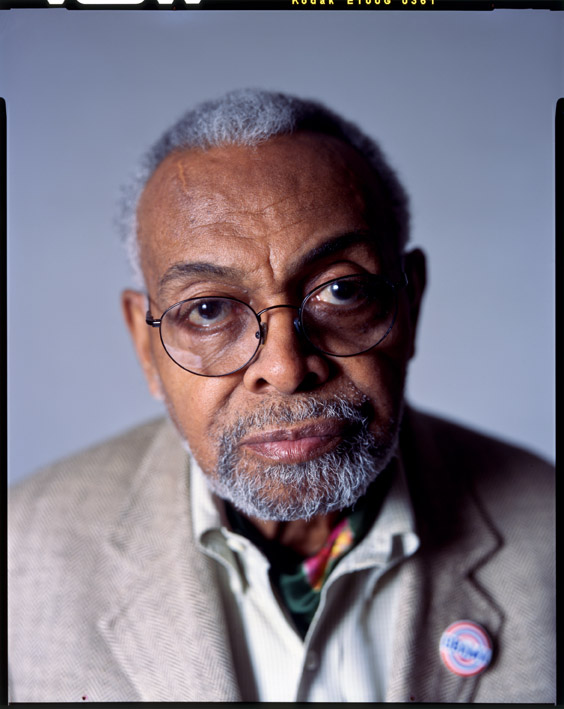

AMIRI BARAKA

7 OCTOBER 1934 – 9 JANUARY 2014

[People might think this is crazy, but I don’t remember when I interviewed Baraka. I know this is actually one of two in-depth interviews I did with Amiri. This was probably, but not definitely, in the nineties. The only other thing to note is that this is not just some random questions. Amiri and I had talked, over the years, about a lot of this stuff. All those references to the early writing came out of conversations and a lot of reading. This is a rough transcript, unedited. That’s it. Enjoy. —KyS]

KALAMU YA SALAAM: When you wrote A System of Dante’s Hell, at one point you decided just to start with memory. You sat down and just started to write your first memories — without trying to make any sense of them or to order them, but rather just to write whatever were your first memories. Is that correct?

AMIRI BARAKA: Yeah. That’s essentially what it is. I was writing to try to get away from emulating Black Mountain, Robert Creely, Charles Olson, that whole thing. It struck me as interesting because somebody else who had done the same thing was Aime Cesaire. Cesaire said that he vowed one time that he was not going to write anymore poetry because it was too imitative of the French symbolist and he wanted to get rid of the French symbolists. So he said he was only going to write prose but by trying to do that he wrote A Notebook of a Return to My Native Land. It’s incredible when you think about that. For me it was the same thing, I was trying to get away from a certain kind of thing. I kept writing like Creely and Olson and what came to me was: “I don’t even think this.” What became clear to me is that if you adopt a certain form that form is going to push you into certain content because the form is not just the form, the form itself is content. There is content in form and in your choice of form.

SALAAM: Is there content or is there the shaping of content?

BARAKA: No, I’m saying this: the shaping itself is a choice and that choice is ideological. In other words, it’s not just form. The form itself carries…

SALAAM: If you choose a certain form, then the question is why did you choose that form.

BARAKA: Exactly–Why did you choose that form?–that’s what I’m saying. That’s the ideological portent, or the ideological coloring of form. Why did you choose that? Why does that appeal to you? Why this one and not that one.

SALAAM: You said you were consciously trying to get away from the form?

BARAKA: Yes.

SALAAM: So, why call it A System of Dante’s Hell?

BARAKA: Because, I thought, in my own kind of contradictory thinking, that it was “hell.” You see the Dante–which escaped me at the time. It shows you how you can be somewhere else and even begin to take on other people’s concerns–I wasn’t talking about Dante Aligheri. See? I “thought” I was, but I was really talking about Edmund Dante, The Count of Monte Cristo. You see, I had read the Count of Monte Cristo when I was a child and I loved the Count of Monte Cristo. Edmund Dante, that’s who I was talking about and I had forgotten that. Forgotten that actually it was Dante Aligheri although I had read that and there was a professor of mine at Howard, Nathan Scott, who went on to become the Chairman of the Chicago Institute of Theology. Nathan Scott was a heavy man. When he used to lecture on Dante, he was so interested in that, that that is how he interested me and A.B. [Spelman] in that. He would start running it down and we would say that damn, this must be some intersting shit here if he’s that in to it. So we read it and we got into it. It was like Sterling Brown teaching us Shakespeare.

SALAAM: So the Count of Monte Cristo is what you were remembering?

BARAKA: Right. Absolutely.

SALAAM: But you were saying A System of Dante’s Hell. Explain the title.

BARAKA: I had come up on a kind of graphic which showed the system of Dante’s hell. You know, hell laid out in graphic terms showing which each circle was. First circle, second circle, etc.

SALAAM: That was Dante Aligheri.

BARAKA: Right. But seeing that, I wanted to make a statement about that, but the memory itself was not about that. See what I’m saying? I was fascinated by Dante’s hell because of the graphic but when I started reaching into Dante, I wasn’t talking about that Dante. I was talking about Edmund Dante. Remember, Edmund Dante, as all those Dumas characters–you know all of Dumas’ characters get thrown down, get whipped, somebody steal their stuff and they come back. All of them do that. Like the Man in the Iron Mask, that could be Africa sitting up inside that mask. The same thing with Edmund Dante, who I didn’t think was hooked up to the earlier Dante, but who was disenfranchished. Despised and belittled. And then his son, the count of Monte Cristo, puts all this money and wealth together. He’s got an enourmous fortune, and he vows revenge on the enemies of his father. That is what was in my mind. What’s interesting about that is first of all that it is Dumas, which I had read as a child before I read Dante Aligheri. I had read Dumas not only in the book but I had read classic comics, you dig? I had read all of that, the whole list in classic comics. That Count of Monte Cristo made a deep, deep impression on me. I think what it was is that I always thought that Black people generally, particularly my father, Black men like him, I saw a parallel with that. They had been thrown down. My grandfather…

SALAAM: And it was on you. You were vowing revenge on those who had thrown down…

BARAKA: Absolutely. My grandfather was “Everett”–which always reminded me of “Edmund”–my grandfather’s name was Thomas Everett Russ. He was the one who owned a grocery store and a funeral parlor and the Klan ran him out of there. Then he got hit in the head by a street light, that’s what they said when they carried him in, and he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair spitting in a can. You understand? So Everett/Edmund, all of that shit. I always remembered him. Like the night that Dutchman came out. I went down to the corner to look at all these newspapers. They were saying all kinds of crazy things: this nigger is crazy, he’s using all these bad words; but I could see that they were trying to make me famous. I said, oh well, I see.

SALAAM: What do you mean “make you famous”?

BARAKA: I could see that this was not a one night stand. They had some stuff they wanted to run about me, either on a long term negative or a long term positive. I said, oh, in other words you’re going to make this some kind of discussion. For some reason the strangest feeling came over me. I was standing on the corner of 8th Street and 2nd Avenue at the newspaper stand reading. I had a whole armful. At the time there were a lot of newspapers in New York: The Journal American, The Daily News, The Post, The New York Times, The Herald Tribune, The Village Voice, The Villager, I had all of them in my hand. A strange sensation came over me; the sensation was “oh, you’re going to make me famous,” but then I’m going to pay all of you people back. I’m going to pay you back for all the people you have fucked over. That was clear. There was no vagueness about that. That came to my mind clear as a bell. That’s why I think that whatever you do, there’s always some shit lurking in your mind and if the right shit comes together–you know the difference between quantitative and qualitative, you know that leap to something else. It could be liquid and suddenly leap into ice, it could be ice and suddenly leap into vapor. When I got that feeling, it was a terrific feeling. It was like some kind of avenger or something. It was: Now, I’m going to pay these motherfuckers back!

SALAAM: Like, all of sudden you now know why you were put here.

BARAKA: Yeah, that’s exactly right. Because until then people wanted to know about the village. I was kind of–not totally, but I was a little happy go lucky kind of young blood down in the village kicking up my heels. I mean I had a certain kind of sense of responsibility. I was involved in Fair Play for Cuba and those kinds of things. I had even worked in Harlem. But I had never determined that I needed to do something that personal and yet that general as pay some people back.

SALAAM: So this was not only personal; it was also taking care of business?

BARAKA: Exactly. I never saw that it was connected specifically to me…

SALAAM: So before your work, your writing, was personal?

BARAKA: Yeah, it didn’t have nothing to do with nobody because it was just me. But then it was, now that people would know my name, I had a sense of responsibility. As long as I was an obscure person, I was going to kick up my heels and be…

SALAAM: Obscure.

BARAKA: Right. Whatever I wanted to do. Althought that’s not a static kind of realization because you were moving anyway. You can’t come to this new conclusion unless you have moved quantitatively over to it. So that was a big turning point because I said, God damn, look at this!

SALAAM: Was that when you got the idea for System? When did you get the idea to write System?

BARAKA: I had written System already, but the point is that that was actually a kind of a summing up of one kind of life to make ready for another. I can see that now.

SALAAM: So System, in a sense, was what made it possible for you to look forward because now you had looked back.

BARAKA: Yeah, it sort of like cleaned up everything. You know how you want to clear the table. I had dealt with all of the stuff, now I can deal with the next phase of my life. Also, there’s this guy, I think his name is Brown, he’s an Englishman. There’s a book called Marxism and Poetry, a very interesting book, but anyway he says that drama is always most evident in periods of revolution. In other words when you get to the point that you’re going to make the characters so ambitious that they are going to actually walk around like they are in real life that means you’re trying to turn the whole thing around. That had been happening to me. I started writing poetry that had people speaking. It would be a poem and then suddenly I would have a name, a colon, and then a speech, then a name, a colon, and another speech. This would be within a poem. The next thing I know I was writing plays. You could see it just mount and mount and mount. You wanted realer than the page. You wanted them on the stage, actually walking around saying it. I had written a couple of plays before Dutchman but the way Dutchman was written was so spectacular that what happened with it didn’t surprise me. I came in one night about twelve and wrote until about six in the morning and went to sleep without even knowing what I had written. I woke up the next morning and there it was. I had written it straight out, no revisions. I just typed it straight out.

SALAAM: So where did it come from?

BARAKA: I don’t know. My life at the time. Whatever was interesting is that whatever had promoted it, I just wrote it.

SALAAM: When you came in did something tell you to write this or did you have a routine that you would write every night?

BARAKA: No, I didn’t do that every night. Most of the time I would get up and work in the morning or the afternoon, even though I did work at night a lot too, but on this particular night, I don’t know. I just came in sat down and started, and typed until I finished. I didn’t even know what I had written. You ever had that kind of experience where you are in that zone or whatever, you just do it til you’re finished, then you go to bed. I said I’ll look at that tomorrow, I’m too tired to look at that tonight.

SALAAM: Had you named it at that point?

BARAKA: Yeah. At first I was going to name it The Flying Dutchman and then I said, it ain’t really the “flying” Dutchman, so I just call it Dutchman. You know the “Dutchman” was really the train, that was the flying in it. But then there was a lot of ambiguity in it in my mind. I didn’t know if I wanted the train to be the Dutchman or the dude to be the Dutchman or the woman to be the Dutchman. So I just said, fuck it, it’s all Dutchman. I had nothing really fixed in my mind; what I’m saying now is all hindsight. At the time I just felt like writing some stuff, wrote it, went to bed and got up the next day trying to understand what I had written. You know how that is.

SALAAM: After you looked at it again did you do revisions on it?

BARAKA: No, not really. I just looked at it. I didn’t understand it.

SALAAM: What do you mean you didn’t understand it.

BARAKA: I understood the lines, the words, but I didn’t really understand what I was really saying. You can understand the words but not understand what you are saying, like: this is a car. You know what that means, but why are you saying that. What does that mean? I didn’t know. So, I left there a couple of days. Then it occured to me the best thing to do with this thing is to look at it. So I submitted it to this workshop I was in. The great benovolent Edward Albee who had made some money off the Zoo Story and Bessie Smith had started this workshop. In fact, Adrienne Kennedy and myself were in that workshop, and quite a few, I thought, intersting white playwrights. Israel Horowitz, a guy name Jack Richardson–Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Momma’s Hung You In The Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad–, McNally, and a couple of other interesting playwrights. I had got up in there because I had started writing this drama and I thought that maybe it would help me. I had written about three or four plays before that, The Baptism, The Toilet. I had written some plays and lost them. We did one of them on the radio, The Revolt of the Moon Flowers. I don’t know what happened to them. Somebody will come up with it.

SALAAM: At this point you were doing a lot of what some people would call automatic writing?

BARAKA: Yeah, but I always do a lot of that. I always allow myself to be as free as I can be within the context of what I think I want to say. I always feel that whatever is in you is probably a little more knowledgable about you than you. The best thing you can do is make sure it doesn’t get crazy; it’s like you’re releasing something out of yourself. It’s like you turn on a faucet and stuff starts pouring out of you but you can’t let it just run wild, but it’s certainly something coming out of you and the best thing is to let it flow but at the same time guide that flow. You can’t just be completely unconscious.

SALAAM: So you want to organize the flow of the outpouring of the self?

BARAKA: Right. You don’t want to just be…

SALAAM: Dissipated?

BARAKA: Right. You want to keep some kind of hand on it, some kind of consciousness. It can’t be completely unconscious.

SALAAM: You had written Blues People, which is a formal study, you had done this major fiction piece, A System of Dante’s Hell, you were doing the poetry, and you had gotten off into the drama. Why were you working in so many different forms?

BARAKA: Because I never thought I shouldn’t. To tell you the truth, I like that I could do that. That intrigued me as a person. No, there are no restrictions on any of this, that’s someone else’s problem, it’s not mine. I do what I want to do and I always thought what gave me that liscense to do that was the fact that I said that, that I had that feeling. I also felt that I never had any kind of strict need to be governed by America in that way. Even as a little boy I always felt that, I ain’t yall cause if I was yall, I wouldn’t be going through these changes I’m going through. I wouldn’t have to be this Black outsider. If I was in the shit with yall, I wouldn’t have to be me, so since I am me, fuck yall in terms of that. I will determine what I do. If I want to write plays, poetry, essays and anything else, I’m going to do that. Why? Because I can do that and I don’t see any reason not to do that. My view was that I’m not restricted by yall because I’m not with yall. Yall have told us that: we ain’t yall, therefore why should we be restricted by yall? I had that sense real young.

SALAAM: But at the same time, when you were first writing that stuff. Like the interview with you about Kulchur and Totem press and the guy was asking you about that. He asked you about being a “negro writer.” The line you used was something like, If I’m looking at a bus, I don’t have to say that I’m a negro looking at a bus pass by full of people, I can just say there’s a bus passing by full of people.

BARAKA: Well, you see, the point is that I could understand that what I felt was in that anyway. What I felt was going to be in that. I could say, I am a negro looking at that but, but even if I said, I’m looking at that bus, it’s still me. The point was how do you invest that actuality into what you have created. How do you make sure that’s in there? It is in there formally because you said it’s in there and you are actually a negro, but how do you make sure that’s in there? Well, once the whole Malcolm thing came about, we got super on top of being Black. I think what I said then was correct except that later on we wanted to make sure that it was actually in there, that it was actually functioning, because it doesn’t change the object. If I say look at that lamp or if I say I am Black, look at that lamp, it doesn’t change the lamp but the question is what recognition of yourself do you want and what interest does that recognition serve. The insistence of Blackness might be its own worth. The real consciousness of being Black might affect your description of the lamp even if you don’t say that. It might affect how you perceive the lamp. That’s what I was wrestling with; yeah, there’s still the bus but it’s also still me saying it. But it is true that the degree to which you want that to be in that description is important.

SALAAM: At this point, your work was not autobiography in the sense that people talk about formal autobiography, but it was autobiographical in the same sense that a musician’s solo is autobiographical. You had your voice and you were telling a story, much of which happened to you but a lot of which happened to you on an imaginative level and not necessarily on what would be called a factual level.

BARAKA: Yeah, it’s like a doubled up kind of thing. Certain things that actually happen give you a certain kind of experience, part of that experience is just a recounting of what actually went down but certain parts of it is just a result of what happened. The experience gives you an experience, the actual experience gives you another experience. So now you’re dealing with what happened and with what that happening made you think. That’s the double up thing. Now, if you try to talk about what happened and about what that happening made you think without roping one off from the other, you know, without trying to separate them then you are creating another kind of form. But let me tell you about the form of Dante. What I thought of–and this is really a musical kind of insistence–I thought I’m going to get something in my mind but I’m not going to talk about it directly. I’m going to get something in my mind and I’m going to talk about what it makes me think about. Like if I think about New Orleans but I don’t mention New Orleans directly but I let whatever kind of imagery comes out of that New Orleans just course as freely as it can while keeping my own hand on it to a certain extent. That is what I called my “association complexes”–I thought up a name for it for some reason. I would say this and whatever came off of that, I would run it. And that’s what Dante was actually about. I was trying to run through the literal to the imaginative. That’s what I was doing: taking an image and playing off of it. I thought that was something like musicians who take harmonies and play of it or taking the melody, dispensing with the melody and playing some other stuff.

SALAAM: You were doing the Cherokee/Koko thing?

BARAKA: Exactly.

SALAAM: You might alter the changes a little bit, but you were definitely changing the melody?

BARAKA: Oh yeah. I didn’t want the melody. The melody was old, auld lang sgyne. I didn’t want that. I figured that whatever I was going to play was going to come up in the same changes but it was going to be relevant.

SALAAM: What was your thinking about what people had to say about System? The reason I’m asking that is because the plays people could relate to as plays, the poems they had references for, particularly the early poems that they could deal with from an academic perspective, but System was a whole other kind of thing.

BARAKA: Like I said, I was trying to get away from what a whole bunch of people were doing, so it didn’t make any difference to me. I saw this magazine for the first time in, I don’t know, twenty or thirty some years, the magazine was called the Trembling Lamb. They published the first five, six or seven sections of Dante and I thought it was a breakthrough because I thought it was something different from what the little circumscribed community of the downtown hip was doing. So recognizing that, or at least what I thought I was recognizing, well, whatever people think, they’ll think differently after awhile. It didn’t make any difference to me what they thought.

SALAAM: So after it came out and you started getting reactions from people, what did you think?

BARAKA: Well, I never got any bad reactions at first. I got some reactions from critics whom I didn’t think knew anything anyway, so that didn’t mean anything. But in terms of my peers, I never got any bad criticism that would make me think I needed to do something else.

SALAAM: You describe it as a breakthrough…

BARAKA: A breakout!

SALAAM: So you make a breakout but all of sudden it’s like you stopped writing fiction as far as the reading public goes?

BARAKA: I didn’t see it that way.

SALAAM: I’m not saying you stopped writing fiction, I’m saying as far as the reading public goes what fiction came out after that?

BARAKA: Tales. But then when I look at it–well, the first couple of pieces in Tales are from Dante. They were written in the same period. And then a lot of those things that are post-Dante are still making use of the Dante technique. As a matter of fact Tales covers three periods, there’s stuff from downtown, from Harlem, and even stuff from Newark. But it is the same kind of approach.

SALAAM: Ok, but then what? With the fiction–the reason I’m asking you specifically about the fiction is because publically we can trace Amiri Baraka the playwright. The plays are there, even the ones that haven’t been produced that much, the scripts have been in circulation and in many cases published. The same for the essays and definitely the same for the poetry. Even when they weren’t published formally, informally they were circulated around. But the fiction, not so. And at the same time, if we talk about a major breakthrough in terms of form, you probably made the biggest breakthrough with the fiction.

BARAKA: Hmmm. I guess you’re right. But, you know, nobody ever asked me to write a novel.

SALAAM: What about the Putnam thing where they asked you to write…

BARAKA: Yeah, but then I wrote it and they didn’t like it. See, the point is this is how I can guage what I can do. I’m a poet. How do I know that? I write poetry all the time. Can’t nobody say shit to me about poetry. That’s where I am. But if you want me to do some other stuff, you’re going to have to say something about that. Like I wrote a lot of pieces of fiction in the last couple of years but that’s because I decided to do that. I had some other stuff on my mind. I thought that maybe–and I still believe this–I shouldn’t write fiction and I shouldn’t write plays unless they are a form of poetry, that’s my view of it.

SALAAM: What do you mean by that?

BARAKA: I mean that’s the only way I think of writing. I would not think of writing a play or a piece of fiction unless it was poetic in the sense of investing the same kind of attention to the lines, and the rhythm, and the imagery. That’s why in the last couple of years I’ve been writing fiction just to see what that’s about. I’m very curious about things like that. I know that as far as the day to day America of my own mind, I’m a poet. That’s the only thing I will do without nobody bothering me or asking me to do. I don’t need nothing or no one to do that. I will write poems because I am alive. I will write them on envelops, books, paperbags. I’ll write on anything in the world, newspapers, paper towels, toilet paper, anything. That’s got something to do with your own obsession, your own modus operandi.

SALAAM: What I’m getting at is that you were conscious that you made a breakthrough with Dante and you were consciously trying to do something different. You were consciously trying to be different and you succeeded at being different.

BARAKA: Which allowed me then to continue doing what I was doing in the first place. In other words, once I discovered that I had gotten past that, then I could write poetry if I wanted to do it. For me, although I am interested in anything at any given time, poetry is the fundamentaly interesting things because it’s the shortest and the most intense.

SALAAM: Yeah, but you write some long poems.

BARAKA: That’s because I can sustain that, but I still believe that poetry is the most intense and the most direct.

SALAAM: In terms of what you do technically, at one point you were trying to write a certain way. Now that you have proved that you can write a certain way, do you still try to write in specific ways or do you just write?

BARAKA: I just write. It like that Billy the Kid story. Billy the Kid was walking down the street and his nephew said he wanted a whistle, so Billy pulls out his gun and pee-owww, shoots a reed through. And they said, how do you do that, Billy, without aiming. Billy says, I was always aiming. The point is that you get skills and understanding that is part of your whole thing and that gives you the confidence to do it, once you know you can do it. Whatever you need to do you can do that because you have already done it, you have thought about it, and you know what that is. To me that’s the initial gratification. I think there’s a lot of gratification in that people don’t even know about. People see the results of it, but there’s a lot of stuff about form and content that nobody will ever really know why they did it. It’s a matter of actually feeling your own self. For instance, Art Tatum. They say Tatum would practice twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day. Now somebody practice the piano sixteen hours a day, when it comes time to play, playing ain’t nothing. It’s effortless. But what was he doing in that crib for sixteen hours.

SALAAM: So what kind of shedding do you do?

BARAKA: Shedding? Well I do that all the time. I throw a lot of stuff away. I mean I write a lot of stuff and throw it away, but it don’t be a long thing, it might be a series of short things. I mean experiments with stuff, with voices, tenses, the abulative, the past perfect.

SALAAM: So you try all kinds of things?

BARAKA: Why not? I don’t want to be held down by the language. In other words, if you just know one thing, well that’s all you can do, but if I know that in this tense I can do such and such, then there’s all kinds of stuff that can come to you imaginatively.

SALAAM: Are you viewing it like music then? You take a given theme, but you know that if you play it in a minor key you will get one feeling and if you put some major chords in it, you will get a different feeling?

BARAKA: Absolutely, absolutely. It’s always music in that sense. I always use the reference of music to justify anything wild that I might want to do in writing. I mean I could go from James P. Johnson, to Duke Ellington, to Monk and be playing the same tune, but it come out different sounding. Listen to Liza for instance. How much more stength do you have to know all three of those references, to have all that laid out in your mind…

SALAAM: And not just to know it abstractly, but to be able to do that. To be able to play like that. That’s one thing about using the music as a reference: all the cats who were innovators, who make a breaktrhough and made a contribution and created a new form, they had first mastered a previous form.

BARAKA: I would agree with that, yes.

SALAAM: So in a sense you were working at mastering the previous shit, so you could do the out shit?

BARAKA: Oh yeah. Absolutely. At a certain point when you get to that (he mimics running scales on a piano), that itself provides the logos for doing the next. You keep saying well I did that shit, so what’s next? if you were free to do what that suggests, what would you do? Play backwards, play it upside down. What if I took just those two notes? You know what I mean? What are the feelings that come out of there.

SALAAM: So then you’re talking about the freedom principle?

BARAKA: That’s what it is. It’s nothing else but that.

SALAAM: Did you ever decide to be a writer and if so when?

BARAKA: I think I decided when I got back to New York from the service. When I first came back I was thinking that maybe I would be a painter.

SALAAM: You were really thinking about being a painter?

BARAKA: Yeah, but at the time I said, well, that’s too much work to buy the canvas, and then to have to buy paints, framing shit and having shit all stacked up in the studio. I thought that, finally, that was too much trouble.

SALAAM: Did you like painting?

BARAKA: Oh yeah.

SALAAM: What did you like about it?

BARAKA: The question of interpreting something from real life and making it into an image of it. That was interesting. Plus, my mother had sent me to all these different classes. I took piano lessons, drum lessons, trumpet lessons–I must have taken piano lessons three different times. I went to drawing and painting lessons. That was when Newark was a real city and they had these classes with teachers all over the place, but then the middle class left to pay us back for burning Newark down around `66. Anyway, that’s why I had a broad kind of aesthetic and knowledge about creating stuff.

SALAAM: Ok, you had all those music and art classes, but you only had one creative writing class and that was in high school. Is that right?

BARAKA: Yeah, but my mother used to have me reciting the Gettysburg address once a year in a Boy Scout suit, and she would have me singing, there was always some kind of approach to word, image and music. I always had that in my mind as points of a triangle.

SALAAM: Of the three, which one held the most interest for you early on?

BARAKA: The music because I always wanted to do that but the word was always closer. I always had more control and more understanding of the word.

SALAAM: So why did you go to New York thinking about being a painter if the music was what you liked and the word was what you could deal with the easiest?

BARAKA: Because I had given up the idea of being a musician when I went away to college. I used to play the trumpet locally until I went away to school. When I went away to school, I never picked it up again. I figure it must have been something. Maybe it was the closeness to the word that relieved me of that other need to deal with the music. It was the closeness to the word and then a beginning to see the word as a kind of music that I could control as opposed to the instrument.

SALAAM: Which you could play but which you couldn’t control as much as you could the word?

BARAKA: I didn’t have the kind of facility. The things I had in my head as far as music, I never got close to except with words.

SALAAM: So what you were carrying around in your head, you tried to get it out with the horn and it wouldn’t come but with words it would come out?

BARAKA: Yeah. With the horn I could just hear it, I heard what I wanted. I heard trumpet players who sounded like I would have played like that if I could have played. I would hear people say, damn, that sound something like Miles, but Miles was a paradigm rather than what I wanted to sound like. As a kid I used to try to play like Miles and be like Miles but actually it changed at different times. At one point I thought Kenny Dorham was closest to what I wanted to sound like, then parts of Don Cherry, than parts of this kid named Norman Howard who played with Albert Ayler. But it all was a kind of word making sound. That’s what I liked about Kenny it would be (imitates a Kenny Dorham riff), that clipped, staccato sound, that sound of actually breaking it down to almost syllables and vowels rather than that logato sound. I guess it was more percussive and sounded more like spoken phrases.

SALAAM: So after Howard you went to the service.

BARAKA: Yeah, after I got thrown out. I wouldn’t never read the stuff asigned for class, I was reading all the time but I wouldn’t read assignments. I had taken chemistry, that pre-med stuff. I got very bad marks in chemistry. The only courses I really did well in was, perdicatably, English, the humanities, philosophy, that kind of stuff, although I got good marks in physics for some reason. But chemistry and all that other stuff, I bombed in that.

SALAAM: You were thrown out because of academic reasons?

BARAKA: Yeah. Plus, I had been thrown out two or three times for various things.

SALAAM: Like what?

BARAKA: Well mostly for academics but also for not being cool. I had a real bad reputation in the dormitory and my room was always filled with merrymakers. A whole crowd would be in there. So the dormitory director was always in there. We had like a crew actually. It was a combination of Jersey, New York, and Philly in the main, but we also had some Chicago people and we even had a couple of hip dudes from St. Louis and Detroit. I guess it was a big city thing.

SALAAM: So there is no currency to the rumor that you were thrown out for eating watermelon.

BARAKA: Well, that was one of my suspensions but that didn’t get me thrown out. What happened was I was just sitting out on campus on a park bench cutting this watermelon in half. I wasn’t even eating. Actually, I was just sitting there with it and was about to cut it because half of the watermelon belonged to another dude, Tom Weaver, who is now a lawyer in Philadelphia. Half of it was his, so I was sitting there. But, you know, we knew what we were doing. We were making fun of these negroes. I was sitting there with it and this guy comes up to me and says, hey, don’t you know you’re at the capstone of negro education and you’re sitting there blah, blah, blah–get rid of it. I said, well, I’ll get rid of the half that’s mine–which was, of course, more bullshit. [Howard President] Bush figured that we were fucking with him all the time. I don’t know if the watermelon qua watermelon was the real deal, although to be sure the negroes didn’t like that, but I don’t know if it was a regular colored person with watermelon and he said that to them and they just left, I don’t know if it would have had the same impact.

SALAAM: …as when it was the leader of the merry pranksters?

BARAKA: Right. He knew we hadn’t just wandered in off the fields with that watermelon. So he figured what are you niggers trying to do, you know you’re trying to make a joke. That was funny to us because we thought they were corny anyway. Nobody there dug Charlie Parker. That’s the way we estimated it. They didn’t dig Charlie Parker so they didn’t know what was really hip.

SALAAM: What year was this?

BARAKA: `54.

SALAAM: When you got kicked out what did you tell your parents?

BARAKA: I told them I got kicked out. There was nothing else I could tell them. That’s when I went to the service, because I was really hurt and embarassed. I was embarassed because they were hurt.

SALAAM: Because you didn’t mean to hurt them.

BARAKA: No, but I was their oldest son. I had scholarships when I went away from home. I wasn’t supposed to just dive bomb like that. I don’t know what they thought really except that they were surprised and disappointed that I had fucked it up like that.

SALAAM: And then you headed on in to the service which was a complete disaster.

BARAKA: Complete! I figured I had dive bombed into the underworld then. I even saw some of the guys I had been in college with who were now officers and I was like an airman nothing. I didn’t have any stripes and then I got to be an airman third class and had one stripe, an airman second class with two stripes, while most of these dudes–hey, some of the dudes I was in school with are admirals and generals now. Andy Chambers the head of the naval something. Tim Bodie the head of air military command or some shit. A lot of these jet pilots was close friends of mine. The guy who was head of the secret service that guarded the president was my roommate in college.

SALAAM: You were kicked out of the air force also weren’t you? What was the specific charge?

BARAKA: I was kicked out of the air force for fraudulent enlistment.

SALAAM: What was fraudulent about your enlistment?

BARAKA: That I hadn’t told them that I was a red, that I had been fucking with people who were on the House Unamerican Activities Committee. It was largely bullshit, but you know. Remember they had the attorney general’s list, which turned out to be completely unconstitutional, but the list which listed these organizations which were “out.” Well, a couple of those organizations I had had affiliation with.

SALAAM: When they asked you or when you enlisted?

BARAKA: When they asked me later and when I thought about it, I told them.

SALAAM: These are your late teens and early twenties; was there any place that you could stay that was acceptable to you and you to them?

BARAKA: I don’t know. I’m still trying to figure that out. When they kicked me out of the village, I thought that was complete.

SALAAM: What do you mean “when they kicked you out of the village”?

BARAKA: When I left. It’s the same thing; when you figure you can’t stay there anymore, when you figure that whatever they are doing you don’t want any part of it, so what’s the difference? In other words, when the management grows intolerable, you have to hit the road. If you don’t hit the road then, that means you’re just fooling around.

SALAAM: You were doing a Trane book a while back, whatever happened to it?

BARAKA: It’s still around. The early chapters, about five or six chapters, are there, plus I’ve written reams of stuff on Coltrane that would go into it. So, I would do that early stuff and I would add all the stuff I written since and that would be the book.

SALAAM: Is Trane the only person you’ve done a book like that on?

BARAKA: No, I’ve got a book like that on Monk, and one on Miles, and probably Duke in a minute.

SALAAM: So what do you do, you just write this stuff? I mean, how do you write stuff like this knowing that it probably won’t get published?

BARAKA: Some of it is published in small journals, some of it is published in Europe, some of it is fugitive stuff published in this review, that review, stuff all over, which when taken together would make a book. I would probably put a circle around it as an overview of the material, but I know there’s enough material to make a book. Oh, I have a book on Malcolm X too. It’s about thirteen or fourteen essays and some other stuff, seven or eight poems and a couple of plays. You know but it’s like people don’t be flocking to that stuff. You tell them about it and that be it. These publishers are not really interested. I mean a couple have asked me for books and I tell them I have those books but they don’t seem like they are interested. Like the Malcolm book, I thought they might be interested in that. They have books out about Malcolm by everybody, people who don’t even know anything about Malcolm; I mean little corny motherfuckers got a thing on Malcolm. See they want the opposite of what would be a mass, democratic, revolutionary line. They are into the debunking and lying period, rewriting and revising history right now. After every revolutionary period they always have a period where they revise it and say: all that stuff you think happened, didn’t happen. The Rodney King syndrome [“can’t we all just get along.”] I mean I’ve got books that actually explain Malcolm, explain the motion from say Malcolm to where we are and where we have to go. But apparently I have to just do those books myself, or create a network, or make a cooperative hook up with other publishers. Another thing I’ve been thinking off, people I know that have the same kind of thing in mind, I thought that if they had a publishing operation, I could be part of it. I would have an imprint.

SALAAM: What’s interesting to me is that you do all this writing in so many different genres and covering a broad range of material even though there is, shall we say, a publishing freeze on the ink that is coming out of your pen.

BARAKA: Yeah, well, what can you say? That’s like a cycle or a circle. You have to live with that.

SALAAM: It reminds me of these jazz artists, back in the day, in the forties and the fifties and the sixties, who were making all this music knowing that most of it was never going to be recorded and put out there.

BARAKA: That’s the way it is. You just have to focus on what you’re doing and do that the best way you can without letting the static be louder than the music.

SALAAM: How did you learn to write so fast?

BARAKA: Necessity. I guess, being an activist you don’t have that kind of spread out time that these people seem to say–the classical, actually the court writers–seem to think is necessary. I’m not in to being a court writer. You have to find a way to make use of your time the best way you can, which a lot of people don’t really understand, but that means you have to do it when you’re conscious of it. You can’t say I’m “going” to do this and I’m “going” to do that. You have to do it when you can do it, and hope you can find it.

SALAAM: And when you can do it, sometimes it’s just maybe an hour here or a couple of hours there.

BARAKA: Yeah, that’s about it. But, you’ll be surprised that when you’re pressed like that a lot of times your mind gets clearer.

SALAAM: So you think that far from being an impediment to your writing, your involvement in activism has helped to strengthen and focus your skills as a writer?

BARAKA: Yeah, it makes you more focused and more rapid. You know you’ve got to get in and get out, you’ve got to say exactly what you want to say, and you’ve got to figure that’s it.

SALAAM: And also figure that you may not get a chance to say this again.

BARAKA: There you go. If I’ve got the chance to do this now, I better walk it right now, because this might be it. And then the question is, let me try to find this shit. But I think that it works because you know time is a precious sort of thing. You don’t think of it as anything else. This is important, it’s precious and this is the time that I have.

SALAAM: Again, using the music as a metaphor, it’s sort of like being in a band and you know yall are going to play tonight. You don’t necessarily know what tunes the leader is going to call but when the leader calls a tune and it’s your solo, you can’t say well wait a minute, I’m not ready for that.

BARAKA: Naw. You don’t have that problem with me. You just say go and I’m on that. The thing is trying to–well, it’s like you got these bullets and you’re trying to find a gun. Hey, you know where we are, right? You understand how we got here? Well, the rest of that shit need not have too much explaination.

SALAAM: In terms of what you use with your writing style, you once said you knew you were a negro because you loved irony–or something to that effect. What does irony have to do with it?

BARAKA: Bloods are always laying down syllables on people, especially when they didn’t have the chance to really jump on them and kill them or else to get away from them, they be hiking them. They be murder mouthing them on the cool. I think it’s not just in the sense of people not knowing what you’re saying, but it’s like heaping it up–you can some shit straight out and then be heaping some stuff on top that makes it straight-out-er, if people dig it. After awhile for the blood, it’s just a style. You’re always using language like that. Like the blue notes, they are always turning them.

SALAAM: Is this part of the ambiguity of language that seems almost intrinsic to the African American use of the word?

BARAKA: Yeah, because the blood’s use of the word has to do not only with the written but also with the spoken, because before the written is the spoken. The written is actually a kind of conduit for the spoken for Black people. A lot of these people their language is always written so that’s where it is. But, at least for our tradition, and I think anybody who is serious about language, always sees the written as a conduit for the spoken for the perception of reality. The spoken word is alive.

SALAAM: What do you mean by “alive”?

BARAKA: It’s live, it’s coming from a live person. It’s in the form of your life, it’s not after the fact. It’s at the time of.

SALAAM: So it is in the now time as opposed to past time?

BARAKA: Right, it is it’s pulse, it’s beating as you hear it.

SALAAM: Taking it to another level, are you saying that the spoken carries the meaning but it also carries the rhythm of the life that utters it?

BARAKA: Yeah. And the sound ot it–the page has no sound on it and that’s a whole different color butter right there because the sound is very important. If you start with the spoken rather than the written, then to get that spoken into that written requires that you do a lot of shit to the written to make it accomodate the life of the spoken.

SALAAM: Is that part of your struggle with writing: to make the sound look like something?

BARAKA: Yeah, to make the sound carry off into a text. It’s like Duke, you can look at Duke’s scores, if you can read, and you hear something but you don’t hear Duke. You could read Afro-Asian Eclispe all you want but you won’t hear it unless you hear it. To hear that, to me, is a totally different experience.

SALAAM: Do you see yourself as a writer being a translater of sounds and of the sound experience?

BARAKA: Yeah, because if it’s not about the sound, it ain’t real to me, because I think of that as real life. That’s why by the time the written catches up with the spoken its obsolete. These people be writing some stuff that people were running long time ago in form and content.

SALAAM: So now form and content, are usually listed as the two major variables, but I would like to propose and get your reaction to this proposal: form and content are basically a western dualism, and that as far as the African and African-American traditions go, you have form and content, but you also have style. So you take somebody like Claude McKay could take the sonnet and work with the sonnet and come out with something like “If We Must Die.”

BARAKA: Yeah but to me, that form was still a straitjacket for that particular content. The difference between McKay and Langston’s stuff is the difference.

SALAAM: I’m not saying that form is irrelevant.

BARAKA: No. But you have to have correct form or otherwise your shit is going to be fucked up. It’s like if I put you in a cop suit, I don’t care what you think, somebody might say there’s a cop, shoot him. There’s a content to form.

SALAAM: So you’re saying that each form–particularly once it has been codified into a specific form–proposes its own content.

BARAKA: Absolutely, because it carries thought with it, and it carries reason. There’s a reason for that form; it coheres with somebody’s language, somebody’s rhythm, somebody’s life, and somebody’s philosophy.

SALAAM: How does it carry the content?

BARAKA: It carries the content by putting a philosophical emphasis on certain aspects of life.

SALAAM: So you’re saying a philosophical emphasis on abstraction will give you a proclivity toward certain forms, and a philosophical interest on sound will give you a proclivity toward other forms?

BARAKA: Yes, for instance, one time I asked a big time capitalist why they were so wary and suspicious of art. He said because it’s unpredictable. That explains it. If you are a merchant and you’ve got to have predictable results for your bottom line, then the form of what you do, you want that to be predictable too. You don’t want form to be a verb, you want it to be a noun. You want form to be a receptacle of whatever you want to put in it. You don’t want the form to be alive. I’m looking for an alive form.

SALAAM: What is a live form for you?

BARAKA: One that relates to what humans still use to communicate, and the ways that they communicate, and the reasons why they communicate.

SALAAM: In looking at the form in some of your work, in some of the short plays that you wrote, often characters would be speaking a language that is recognizable as standard english–and I’m not talking about slang, I’m talking about some way out shit.

BARAKA: Well, if you listen to the rappers, or like I was looking at this movie, A Thin Line Between Love And Hate. Well the way they talk in there that’s not just regular Broadway theatre language. All that stretching and bending of words, and different voices, and emotional kinds of uses of vowels, and songs in the middle of talking, that’s got to do with a living kind of life style not the written text that referenced in dictionaries. You can’t find that in thesauruses and stuff. That has to do with Black thought, Black music, Black lifestyle. The ballad form, communication by tones and rhythms. To get that into the work is hard on the page. You have to have notations if you’re going to use pages.

SALAAM: Like in Home on the Range and Experimental Death Unit you have people talking all kinds of stuff. How did you write that–I’m asking a technical question. Did you put words in a hat and just pull them out?

BARAKA: No, I got the rhythms of what I thought they might be saying.

SALAAM: What do you mean by rhythms?

BARAKA: Well that kind of people I was creating, well their personalities would make them go (does a chipper sing-song rhythm).

SALAAM: So you heard the sound of what they would sound like, but how did you get the words?

BARAKA: That’s what I heard. You just try to make an omnamyopoetic representation.

SALAAM: Omnamyopoetic? Is that a technique you use often.

BARAKA: Yeah, always. That’s what bebop is. You take the rhythm and make it into a vocal sound.

SALAAM: So the rhythm becomes the melody and the harmony?

BARAKA: Yeah, which it is anyway, to me, always, but that’s another thing. I’m still working on that.

SALAAM: Again going back to the music, when you listen to a lot of James Brown, he started off in a classic rhythm and blues bag, but some where around the mid sixties he started changing and by the seventies he was in so deep a funk that everything in the band was playing rhythm, it didn’t matter what instrument it was.

BARAKA: That’s right. That’s what you hear in the best of the jazz people, too. Blakey, Trane, Monk, Duke, the rhythm is principal.

SALAAM: So this omnamyopoetic form–not form–but approach that you’ve talking about, this is a prioritizing of rhythm in your approach to writing. Is that a correct assessment?

BARAKA: Right. It’s rhythm as language.

SALAAM: So you first hear what the characters would sound like.

BARAKA: I’m hearing it as I write it down.

SALAAM: And hearing that sound leads you to what words to choose.

BARAKA: Those are the words. When I hear them, they are saying words, I’ve just got to try and figure out what those words are. The thing is to transfer them to the page. The translation of rhythms.

SALAAM: So how does that work with your poetry?

BARAKA: It’s the same way actually. The rhythm is the leading factor, even the theme has a rhythmic aspect to it.

SALAAM: Has that always been or has that been something that has developed over time with your work?

BARAKA: It’s been clearer. It’s always been but it’s clearer as I’ve gotten clearer.

SALAAM: Given that for all artists there are moments of clarity that are so absolute everybody can see them, and whether the artist digs the product of that clarity or digs whatever came out of that is another question. For example, Kind of Blue will always be one of Miles’ more definitive statements–not to say that nothing else he did was important but…

BARAKA: Yeah, that’s all rhythm and harmony. Nothing but rhythm and modes…

SALAAM: Rhythm and basically the feelings that you can project through those rhythms. Then you’ve got A Love Supreme for Trane. Charlie Mingus said Tiajuana Moods was his, and if not Tiuajuana Moods, you had Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. They all had strong rhythms. In terms of your writing, what is your Kind of Blue, your Love Supreme?

BARAKA: Why’s actually says that in a lot of ways.

SALAAM: Why’s is actually a score rather than a book of poetry? I mean, you indicate the musical references, but until you hear it recited, sung and played, you haven’t really dug it. You can’t fully appreciate it just by reading the score, you’ve got to hear it.

BARAKA: I think you were right in saying that Why’a is a musical score. It is in a lot of ways. It lays out that music to show you the kind of feeling that the words are supposed to be attached to.

SALAAM: You don’t see that in your other work?

BARAKA: A lot of the poetry I think is like that. I get fixed on a particular rhythm and I can get words out of that.

SALAAM: What about with the prose, anything in the prose?

BARAKA: Well, to me, the prose is an extension of that. I don’t think you can write prose unless you’ve got a rhythmic understanding of language, a feeling. When Ismael Reed says he doesn’t hear any music when he writes, I say, oh yeah, I can understand that because that just tells me that you think you write purely from the top of your head. That ain’t nothing.

SALAAM: Well that ain’t all for sure.

BARAKA: To tell me that you’re writing from the top of your head is to say simply that the whole depth of your experience is not valuable.

SALAAM: It’s also to say that your heart ain’t it, not to mention your gut and your groin.

BARAKA: Can I quote you on that. I can dig it. You know, pretty soon, they will have some stuff with which to write things down that will be more than just words. It will have sounds, rhythms, dances, facial expressions, all of that, you know what I mean?

SALAAM: All of that will be part of the presentation. So, why haven’t you recorded more?

BARAKA: Well, I haven’t had the time really but I is in a minute. Probably early next year, I will start having stuff coming out.

SALAAM: Given your breakthrough with System of Dante’s Hell–you personally breaking away from a lot of other contexts and trying to achieve your own voice–and given that you continued to write fiction but not much of it was published after Tales, why do you think that your fiction has not published. You’ve been able to get your prose, and your plays even–and that’s odd to get more plays published than fiction–why do you think that is?

BARAKA: I don’t know. I’ve got more stories than people think. It’s just a question of what you have time to focus on.

SALAAM: But how can you get more plays published than fiction?

BARAKA: Because I had plays done, performed, and therefore, for the commercial eye, that means there’s more of a reason to do it, I guess.

SALAAM: Did you ever think that maybe it was because what you were doing was too far out for most of the fiction publishers?

BARAKA: I know some of that was the case, but the fiction will come out when it comes out. I have several novels–they be talking about these people writing novels now, but these are novels I wrote fifteen years ago and they are stranger than a lot of that shit they praise now. I think it has to wait until there is an appreciation of it.

SALAAM: How can there be an appreciation of it before it arrives?

BARAKA: Because other people will be doing stuff like that, and then the whole question of language can be a little deeper than it is. It’s not there yet, but it will be there in a minute. I thought it was coming a couple of years ago, but…

SALAAM: What are you looking forward to doing?

BARAKA: I’m looking forward to getting all the books I have written published. I’m looking forward to writing a book on how to make revolution in the United States. That’s the one that I really want to write. The whole connection, historical, political, cultural.

SALAAM: So you want to write a David Walker book and get yourself killed?

BARAKA: I don’t know about that.

SALAAM: You understand what I’m saying?

BARAKA: Yeah, I know, but that’s what has got to be done. The book that I’ve got to write which I’m ready to write now is how to make revolution in this country, which is a broad kind of philosophical and agitational work. That’s what I’m trying to do.

SALAAM: What is the easiest way for you to write: typewriter, pencil or computer?

BARAKA: Computer now, but it’s difficult to do any of it when you don’t have the time. I have to handwrite a lot of stuff only because I can’t always get to a typewriter or computer.

SALAAM: When you say computer now, why do you say now?

BARAKA: It used to be typewriter.

SALAAM: Why the typewriter as opposed to hand? You can type faster than you can write?

BARAKA: Oh yeah. I don’t want to have no hookup with a pencil. I want to get it done. I don’t want to be messing around with it in no kind of physically debilitating way which is what handwriting is for me. Why should you handwrite it when you can do it another way? All I want to do is get them down.

SALAAM: And you find the computer a better tool than the typewriter?

BARAKA: Absolutely, because you can store it and all of that. You can print out a whole lot of copies at once.

SALAAM: So you’re not talking about he specifics of putting it on the page, but rather what can be done with it once you’ve got it in the computer?

BARAKA: Right.

SALAAM: Do you find the cut and paste, or going back and being able to insert or delete easily, do you find that useful?

BARAKA: Absolutely.

SALAAM: When you write do you throw away much?

BARAKA: Yeah, more than you think. But I throw it away in a swoop. That’s the way that I get it. I write it in a swoop and if I don’t like it, I throw it away, and if I do like it I throw it on a pile. For me, once I get on it, once I get the chance to do it, seven times out of ten it’s going to be something I want. If I get the chance to do it, it ain’t going to be no problem.

SALAAM: Do you do a lot of thinking about it before you write it, or do you just do it?

BARAKA: Sometimes, I think about it but most of the time I just write it. I have it in my mind for a long time whether I know it or not, so when I get to it, it’s coming out of there. That’s it.

SALAAM: Is there a difference for you writing on assignment as opposed to on inspiration?

BARAKA: Assignment sometimes is hard because it’s a task even if you want to do it, and a task usually has a level of resistance to it, for me anyway. It’s still something you want to do but it’s just that you might also have something else you want to do at the same time.

SALAAM: You were at one point noted for the record reviews, music columns, and stuff like that. At one point you were the “hottest negro” doing that. At one point you were the first Black writer to have a column in Downbeat?

BARAKA: I used to write for them all the time, but that was always give or take. You never knew. I was on the porch.

SALAAM: So you would throw your columns up on the back porch and pass back the next day and see which ones they took and which ones they left?

BARAKA: Yeah, that was it. And then they came with shit after I got out of there saying “Is LeRoi Jones a Racist” on the front cover. I said, these motherfuckers are really out, this is the dog.

SALAAM: Did you view those as assignments or as inspiration?

BARAKA: I wanted to write about the music so it didn’t matter.

SALAAM: Did they ask you to write a column about such and such, or did you just present stuff to them?

BARAKA: I asked them to write a column: Apple Cores. That was it.

SALAAM: You were basically writing whatever you felt like writing.

BARAKA: Yeah.

SALAAM: Writing the liner notes, how did that work?

BARAKA: There was a blood in charge of A & R (artist and repretoire) at Prestige, Esmond Edwards. He the guy who set that up–for which I am ever grateful.

SALAAM: Why were you grateful?

BARAKA: Because it was a gig and I needed that gig very badly. It was a real job and he gave it to me, maybe once a week. I used to do fifty dollars a liner note and I would do four a month. At the time that was like a monster, a blessing.

SALAAM: How would you go about doing the liner notes?

BARAKA: I would get the record and bam, I would play it and while I was playing it, I would write it.

SALAAM: Did you talk to the artists, interviews and stuff, or did you just write from your own reactions?

BARAKA: If I could get them, I would talk to them. Call them up. I would always need a lot of help and I would always want to talk to them anyway. I was always interested in jazz musicians, what they thought and what their lives were like.

SALAAM: If you had to leave and somebody said you can put a book together and we’re going to put them in a time capsule, plus we’re going to put them all over the world–maybe about twenty of them in different parts of the world, and they are going to opened up a hundred years from now, what of your stuff would you put in there?

BARAKA: Ahhh man. I guess Blues People would be one thing.

SALAAM: Why Blues People?

BARAKA: Because it tries to lay out some stuff that might be valuable to people even in the future.

SALAAM: What else?

BARAKA: I don’t know. I’d have to think about that. Certainly Black Fire and Confirmation.

SALAAM: Which brings up the question of editing. A lot of people think you made your mark first as a poet, but actually you made your mark first as an editor and a publisher. Was that by conscious design? Did you say to yourself I think this is the way to really break into this stuff.

BARAKA: Yeah. I thought that the best thing for me was not to wait for the people to come publish me but to publish people so that I could publish myself and whatever else was happening to make a way for a whole group of young people.

SALAAM: So you consciously set out to become an editor and a publisher?

BARAKA: Yeah.

SALAAM: Where did you get that idea from?

BARAKA: From me.

SALAAM: I asking this because what you’re saying implies that you wanted to do more than just get yourself in print.

BARAKA: Yeah, that’s right. I thought that it would be better to get everything that was happening because that would make whatever you were doing more significant. It was not just you, it was a lot of people that had these ideas.

SALAAM: When we read some of the letters, statements and interviews with people form the village period about you, when they would mention you, a lot of the writers and publishers had a lot of respect for your talent as an editor. Did you think of yourself as talented as an editor?

BARAKA: Yeah. I thought I knew how to get together something that people wanted to read. I figured if I found something I wanted to read then I knew a lot of people would like it.

SALAAM: How did you develop that talent?

BARAKA: I think by knowing the field and know the varieties of that discipline, knowing about magazines and about other kinds of publications, which I did know a great deal about.

SALAAM: How did you know about that?

BARAKA: While I was in the Air Force I had read everything in the world.

SALAAM: Is that what you did while in the Air Force instead of Air Forcing?

BARAKA: Yeah, I was the night librarian, and I ordered all the books. The woman who was the day librarian found out I knew all about the books so she hired me as the night librarian. So the whole time I was at Ramey when I wasn’t up flying, I was in the library. I ordered all the books and the records. I had my own group in there. We would sit there get drunk and read and listen to music.

SALAAM: You mean you went through that whole library?

BARAKA: Yeah, I stocked the sucker. Not only did I go through it, but I stocked it. I would go through all the bestsellers and the publisher’s catalogues and find out what was happening, what was I supposed to know about, what was I supposed to read.

SALAAM: Basically you read not only what they call the classics, you read everything that was happening?

BARAKA: Yeah. Bestsellers, classics, whatever. I would check it out and find out what was it, what was it supposed to be, who was a Kafka. I would search around until I would find Kafka, I would read it, and then I got it.

SALAAM: Where there any particular individual editors whom you liked?

BARAKA: No. I used to read so much different funny shit. I liked a thing called Accent, that was the University of Illinois. When I got out the way Johnathan Williams did his Jargon Books. Then I started seeing other stuff from people all over the world, different magazines and stuff. From that I could see what it took. The form would be functional in the sense that it would be alive and it would carry the content in the way that you wanted it to be understood.

SALAAM: By the time you started doing Yugen all that other stuff, you had already peeped most of the stuff that was out there and you had made a conscious decision that this is what I want to do.

BARAKA: Yeah.

SALAAM: So then, Black Fire is no accident?

BARAKA: Right. It was just a matter of me getting to that particular gig, because any place I would be, any group of people I would be with, I would try to collect, sum up and anthologize.

SALAAM: When you say any group you would be with you would try to collect, sum up, and anthologize, why? What was the motivation behind that?

BARAKA: So that it could be a lasting kind of presence. Something that indicates that your experience wasn’t just personal and transient, that it had an objective kind of impact and function in the world.

SALAAM: So that if people want to look at what was getting ready to jump off with American fiction, you had to pay attention to Moderns, right?

BARAKA: Right.

SALAAM: Are you saying that this was a conscious decision to try to codify this is what’s happening right now in that particular genre?

BARAKA: Right.

SALAAM: And you did the same thing with Black Fire?

BARAKA: Right.

SALAAM: And you did the same thing with Confirmation, although a lot of people slept on that? Why do you think people slept on Confirmation?

BARAKA: Because they wanted them to. What are you trying to do Amiri?

SALAAM: And who is they?

BARAKA: The controllers of public information?

SALAAM: Are you going to do anymore editing?

BARAKA: Yeah. I’m thinking of some stuff that I would like to do.

SALAAM: Like what?

BARAKA: Well I’d like to take Black Fire and extend that and make it a statement of then through now.

SALAAM: In listening to the tapes and the recordings and everything that you have done over the years, has performance shaped the way you write and use your poetry?

BARAKA: It has something to do with the shape that it takes, obviously, but not in terms of the catalyst. I guess the catalyst is ideas and emotions. Sometimes you can see that the very kinds of methods that you use, remain in your consciousness, that is, if you use a lot of rhythmic kinds of methods and processes, then it means that even when you’re not doing that, that kind of presence is going to linger in your skull.

SALAAM: You have three specific recordings that you did completely–I mean you as a soloist and not just one or two cuts on a compilation. You had Black & Beautiful, Soul & Madness which had an R&B base partly and a new music base partly. That kind of showed two different directions all at one time happening.

BARAKA: That’s because that’s what I dig. I wrote a thing called The Changing Same; it’s my feeling that the music is a whole. We get blinded, not necessarily blind but the blind folks and the elephant. We get a piece of where we’re coming from, where we are at in our time, place, and condition. We get what we’re able to get, what we can dig, or perceive, or understand, but if we can dig the whole thing and dig that it all belongs to us, then we could use it like we want to use.

SALAAM: What made you think, or feel, that putting a piece out like Beautiful Black Women with the Smokey doowop, that the people who would dig that would also dig something like Form Is Emptiness?

BARAKA: Because they go into deeper shit in their churches. Number one. These people [avant garde artists] think they out, they need to dig these negroes in these churches jumping up and down with their eyes rolling around in their head smoking a cigar. I haven’t seen anybody doing that on stage. All that whooping and hollering and rolling on the floor and kicking their feet in the air, and starting to scream about Jesus, Jesus. You ever seen somebody wild with Jesus? That’s what I was saying about James Brown long time ago. Poets was thinking they were getting out there but they had better check James Brown. His voice was further out than Ornette and them because James’ voice had more himmy, dimmy, shimmy, scrappers in it that you can hear. To me it was just a release of the whole consciousness.

SALAAM: When you got to Nationtime it seemed like you were able to orchestra that whole sweep of the music, from the chants with percussion, to the R&B and doowop, to the new music and everything.

BARAKA: Yeah, because I feel it all. it obviously wasn’t a commercial catalyst. We were doing it because we wanted to do it. We were obviously digging Martha and the Vandellas and digging Smokey, just like we were digging Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Trane. To us it was just different voices in the same family, different voices in the same community. I know that the screaming and hollering in James Brown and the screaming and hollering in Albert Ayler was the same scream and hollering, you understand.

SALAAM: Yeah, coming out of different mouths but the same spirit.

BARAKA: Right, the same sound, different experiences they had, but it was the same: gift of song and story, same gift of labor and spirit. It’s the same gift, like the gifts of Black folk DuBois talked about.

SALAAM: Do you consider Nationtime the most realized of all the recordings?

BARAKA: In some way yes because of the formal kind of preparation and the fact that the people we were working with we had worked with both organizationally, ideologically and artistically, so there was a kind of ensemble strength. There are some other records I like the stuff we did on them, you know that record with David Murray, but Nationtime I like for the whole ensemble, plus we had some hip people like Reggie Workman and Gary Bartz. And we had the scratch [money] to put it together and do it. I guess it was like some Earth, Wind and Fire stuff, we had a chance to get the shit, plan it, go over it, and then go in the studio and get down with it. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to go from rhythm and blues, to new music, to Africa at will.

SALAAM: When you got to New Music, New Poetry, with David [Murray] and Steve McCall, that was a point when you were introducing marxism into the lyrics of the poetry and the music was new music but at the same time it had sort of like a funk thing but not quite.

BARAKA: Well, see, those elements are in David. David, like Albert [Ayler] had that. That’s why I was drawn to them because their playing includes the whole spectrum, the new and the old, the main and the out. When I worked with them I knew that they were going to do some stuff and whatever it was, it was going to have those elements in it. Wherever you go with it–sometimes it’s going to sound straight out funky, sometimes it’s going to be reaching into the way-gone-asphere, it’s going to be as varied as the different aspects of our music is.

SALAAM: I have tapes of you reading from as early as 1962 or `63 and even back then the sound of your voice is much the way it is now–your sound, in the musical sense of sound, is relatively the same. You hear it and say, I know that, that’s Baraka. But how you use your voice today has changed dramatically. Now when you do the poetry programs, first of all without saying anything–you don’t introduce the music that you hum or sing, you just go into it and start beating on the podium to get the rhythms and humming or scatting the melody, and then the poem floats in on top of all of that, but you are consciously setting it up as though you were a band and not just an individual standing up there reciting poetry.

BARAKA: Right. That’s because I learned that you can’t be limited by what you feel by the circumstances–I mean you are limited but you ain’t gon be limited. I can’t have a band with me all the time. So what does that mean? It means you have that musical insistence without the band, although you feel that, that’s why you call for a band. It’s like DuBois told Shirley [Graham DuBois], she said I don’t have any pencil, no crayon, no books, what should I do? He said, be creative. So, that’s the only thing you’re left with. It occurred to me that as a musical presence the human is the instrument, that’s where all those instruments come from. We have created all those instruments, so we must be able to create them in some kind of approximate way by ourselves.

SALAAM: But you have consciously decided that creating the music is an essential aspect of performing the poetry?

BARAKA: Yeah, because it makes me get off the line.

SALAAM: Come up off the page?

BARAKA: Exactly. Otherwise you be just reading, which is what they do in symphony orchestras. They put the score down there and they read it, but that ain’t what we want to hear. In that sense the self gratification in terms of what you dig at the same time puts it in a more live kind of form. And that’s what I’m interested in. A lot of times people’s poetry be dull because they are not interested in it. They’re not trying to communicate to you their ultimate concerns even if that’s what they were doing once in that poem. They are going through a formal process. It struck me that to get away from the incessantly formal or the overly formal nature of readings–remember that if you’re reading, if you’re a professional poet, that’s your gig, that’s your job. If you’re going to approach it without trying to reach the element that inspired it in the first place, well, why do it?

SALAAM: At the same time, does using the music make the “I” less the individual I and more the collective I? For instance, when you use Monk’s music, that’s everything Monk means to you but it’s also everything Monk has meant to other people in the world.

BARAKA: Absolutely and it extends that kind of feeling which is the essence of what that poetry is. If the poem has some relationship to that piece of music–other than arbitrary–then that relationship is going to be stated a little more forcefully too.

SALAAM: At one point you were talking about having the music be popular with the people. I assume that when you were talking about that, you were implying that there had to be a connection between what you were doing and what people were receiving. Did you mean the audience as consumers or the audience as validators, or what? How did you mean that?

BARAKA: To reach them not because you were trying to sell them something but rather to turn them on, in the old sense of that, to tell them what’s happening. You’re trying to teach and reach, you’re trying to educate and agitate. Propagandize. To mean all art is propaganda but not all propaganda is art, like Mao said. You try to move people to what it is that you understand about the world.

SALAAM: You have attempted to make a statement about what direction poetry should go in other than an academic direction. Was that conscious on your part?

BARAKA: Certainly. That’s something that comes with degrees of your own self-consciousness. At the point that I could see that there was this and that, I certainly wasn’t interested in that and I was doing this, and the more you do this, then the more openly you are opposed to that. Because you can be opposed to something objectively and not even know it. Somebody can do a close reading of your shit and tell you. At another point you become aware of it, or you are aware of it from the jump. But the more you are conscious, the more you will be conscious.

SALAAM: Ok, so describe your writing style. Do you consider yourself an avant gardist, a mixture of surrealism and realism, what?

BARAKA: I don’t eschew any form, that’s my line. I’ll try anything.

SALAAM: So you’re like want these dudes walk up on a stage and tell the band, call whatever you want to call, I’m with it?

BARAKA: That’s right, as long as it ain’t nothing completely corny.

SALAAM: What you’re doing with fiction stylistically, don’t you consider that really different from what most people are doing?

BARAKA: In some ways yeah, because of what I’m attempting to do. As far as the evolution of stuff, if you see something that seems new to you, you understand that it’s different from a lot of stuff, but that’s not it’s total value. It’s value is that it gives you a sense of being somewhere you are not, of saying something that you haven’t, or giving some kind of presence to some kind of feeling or expression that you haven’t done before. But in terms of it being different from this, this, and that, I’m aware of that but I don’t ultimately think that’s the most valualbe thing about it. I just think that’s the way I am.

SALAAM: So you’re saying, I am different but that ain’t the important thing. The important thing is that by articulating this difference I can open up some stuff that hasn’t been here before.