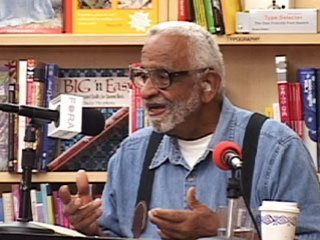

NELSON PEERY

Nelson Peery is the author of “Black Fire: The Making of an American Revolutionary,” a memoir that won first prize in the Midwest Authors Award for Biography. He has been interviewed by journalists, radio and television hosts, and spoken on campuses throughout the country. His books, essays and articles raise profound questions for everyone fighting for social change.

Nelson Peery grew up in rural Minnesota, the son of a postal service worker in the only African-American family in the town. Hoboing across the Western U.S. supplemented his education during the depression. It was an experience that no school could teach about racism and the American economy. His book, “Black Fire,” describes these years, as well as his years in the U.S. Army.

He wrote “Black Fire” because no one had told the story about the Black soldier during World War II and he wanted to set the record straight. He returned from the war determined to continue his political activity. He wanted to show how a person becomes a revolutionary from their life experience and the conclusions they come to about what must be done to make America live up to its promise.

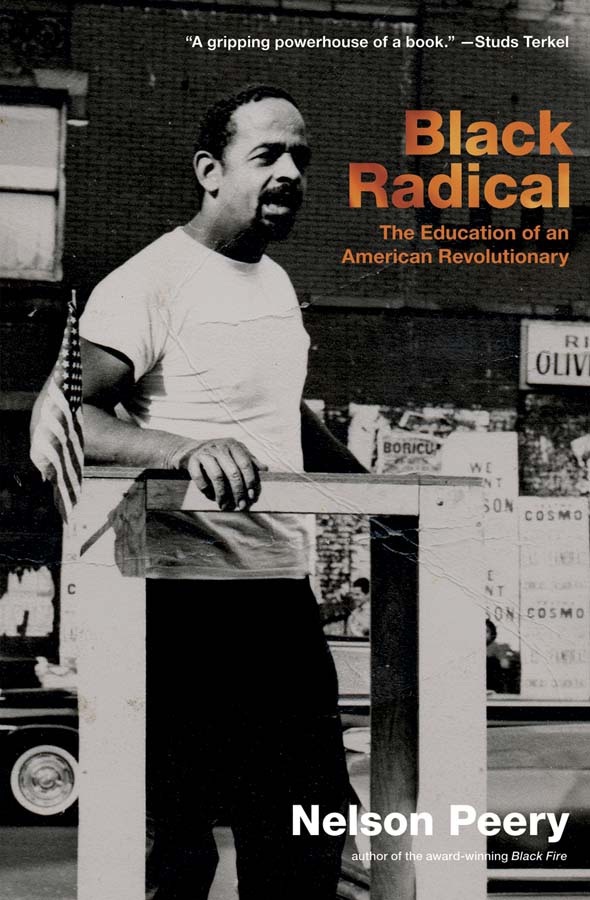

In his new electrifying sequel, Nelson Peery picks up where Black Fireends. “Black Radical: The Education of an American Revolutionary,” begins with the author’s integration back into civilian life following the war. It describes the development of his revolutionary consciousness as he attempts to move from first-class soldier to first-class civilian. The book offers a rare perspective and a new and fascinating vantage on the crucial historical period from 1946 through 1968, including the postwar, grassroots struggle for equality and democracy led by Black veterans, the battles of the Black Left and revolutionaries during the McCarthy inquisition and their role in the Freedom Movement, and the 1965 Watts rebellion in Los Angeles, where Peery and his family were living at the time. Above all, it is about the education of an American revolutionary, amid the continuing struggles to bring to life the ideals that Peery and so many others fought for in World War II.

Nelson Peery’s other works include: “The Future is Up to Us;” co-author of “Moving Onward From Racial Division to Class Unity,” a book that discusses the historical evolution of racism and what makes today different; a pamphlet, “African American Liberation and Revolution in the U.S.”; numerous essays such as “School Days,” in the book, “Teaching for Social Justice,” and “The Birth of a New Modern Proletariet,” in the book, “Cutting Edge,” and many more writings on African American liberation, the global economy and the vision of a new cooperative America.

>via: http://www.speakersforanewamerica.com/nelson.php

The Education of An American Revolutionary from Cody's Books on FORA.tv

All Revolutionaries

Ain’t Built the Same

by Dax-Devlon Ross

Black Radical:

The Education of an American Revolutionary, 1946-1968

Author: Nelson Peery

Publisher: The New Press, 2007

Black Radical: The Education of an American Revolutionary follows author Nelson Peery’s journey as a political revolutionary in the post-World War II era. The memoir is the sequel to Peery’s award-winning memoir Black Fire, which, among other things, told the story of Peery’s experiences during the Depression and his political awakening as a soldier in the South Pacific. First off, it was a pleasure to read something so earnest, so forthright and unpretentious. If one thing shines through in Peery’s writing it is his style of presentation. Irrespective of his commitment to revolution, Peery’s writing comes across as belonging to someone who genuinely devoted his life to a higher cause—in this case, serving humanity.

One has to appreciate the book’s sense of balance, which, again, says something about the writer. Peery doesn’t just say he is dedicated to the working class or even live his life among the working class — though he had opportunities to live otherwise — he writes his story from the perspective of a common individual (AKA proletariat). It would have been easy for Peery to have written solely about the Communist Party or about the various social movements of the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. He could have written heroically about himself, inserted himself into the sweep of history; instead he resists the compulsion to self-aggrandize in favor of the simple, quite often unromantic reality of fighting for change. Revolution, the one Peery lived through between 1946 and 1968 — the period the book covers — involves all of the peculiarities and particulars of everyday life: marriages, divorces, childbirths, deaths, prosperity, action, inaction, depressions. To be a revolutionary, according to Peery , is to be a human being willing to hold steadfast to his/her faith in peace and plenty for all, not just a few. In Peery’s world being a revolutionary requires nothing special. Anyone willing to acknowledge the shortcomings of the present — their own included — and continue fighing for a better world anyway (which we all do!) has the revolutionary spirit already in them.

As history, Black Radical offers a ’People’s History of the Cold War and the Black Revolution.’ The rise of McCarthyism, the rumblings of the civil rights movement, and the apogee of the Watts Rebellion are all told through the humble eyes of a communist who made his living laying brick. This is not a story written from above the fray or in the warm mist of victory. This is a clear-eyed odyssey through the “Black Bottoms” of mid-century Cleveland, Detroit, New York, Minneapolis, and Los Angeles. Through it all we see Peery’s family torn apart, the wilting of his first love, the disintegration of his first marriage, the disappearance of comrades, the painful defection of others and the countless untold casualties of the repressive Red Scare regime. We see Peery bumping against the currents of the historical moment not only as a working person, intellectual and black man but as a serious radical, all of which, consequently, placed him at odds in practically every social setting he found himself in. In Black Radical the whole tangled mess of this nation’s troubled growth spurt from the precipice of fascism to the edge of revolution unravels against a single, simple man’s life, and it is better for it.

As a meditation on life, BR offers us all important lessons about what it meant to be a revolutionary. It meant keeping your mouth shut even when you’ve been belittled by a condescending ranking white comrade or a bigotted southern cop, getting on a bus to go underground at a moment’s notice, living long periods without a name or a connection to the world you loved, being tracked and trailed by the FBI and its army of informants. We often picture the revolutionary in a romantic light. Doing so feeds our need to believe life can be lived on a grander scale, even if that life is brief and fraught with pain. Revolution, though, is organizing people, educating people, creating consensus among people. It is retreating when your heart longs for a fight, pausing at the critical juncture where the personal risks clouding the political. Revolutionaries bide their time the same way prisoners learn to. They discipline themselves. They don’t waste time pitying themselves. They look forward even when the weight of the past is bearing down on them. In many respects revolutionaries are fanatics and zealots. They must be. History depends on their madness to propell us all forward.

At the same time theirs is also, quite clearly, a life worth living; for the revolutionary ideal, the vision of a future free of exploitation, feeds the revolutionary’s spirit with something that capitalism’s promise of prosperity simply can not. Peery’s life is instructive here. By choosing to be a part of the events of his day — to be accountable for his time here — his life flowed in the direction of the momentous. Leadbelly, Paul Robeson, Malcolm X — these are just a few of the well-known names that pass through the pages ofBlack Radical. But while Peery acknowledges these heroes respectfully, he does not indulge in sychopantism in order to make himself appear more important by association. He would rather tell us about the nameless and faceless, the few who hold up the wall of resistance while the rest of us wait for the ‘right’ time to join the revolution. In fact, though Peery dedicates this book his late wife, it could easily be read as a memento to a generation of unsung heroes who kept the beat of resistance alive when its pulse teeterd on the brink of flatlining.

As literature, BR picks up where Ralph Ellison’s hero in Invisible Man leaves off. The parallels between Invisible and Peery should not be overlooked by any serious reader. Both stories concern thoughtful and articulate young black men from the South who are attracted to the Communist Party. Both stories culminate in a riot. But rather than give up on both his people and the class struggle the moment he feels betrayed by both, Peery chooses to fight on, and to work to build the party and the movement that he wants. Whereas Invisible virtually accepts his disinherited status, Peery refuses anyone else’s claim of right to struggle for human freedom. BR’s response to IM is that communism isn’t the problem. The people who become communists — middle-class whites whochoose to fight alongside blacks who have no choice but to fight, for example – are the problem. As an historical footnote, it is important to remember thatInvisible Man won the National Book Award at the height of the anti-communist mania. Despite Ellison’s professed allegiance to art above all else (and the book’s literary brilliance), we can not overlook IM’s politics if we hope to understand its critical success.

As a writer, Peery is more than capable. He does not try to dazzle us with his style. His prose is fluid. His stories at once effectively capture his inner emotion and the spirit of the age. When he dons his polemicist cap it is always within the context of the story itself, always in stride. Peery’s true gift as a writer is to make the complex concrete. He brilliantly bridges the gap between the political theorist and the blue-collar worker as only someone who has lived in both worlds can. Like any skilled craftsman he focuses on the doing the work correctly so that it serves its purpose. All of the bells and whistles that too often mar otherwise important books are, for the most part, left in the bag. As refreshingly straight forward as BR’s style is, however, it is also a luxury: Nelson Peery has a story to tell. He does not have to unearth it or manufacture it or invest it with filler (gatuitous sex scenes, stereotypical signifyin’ scenes, romanticized standing up to the Man scenes) to make up for the life he didn’t lead but would like to tell others about nonetheless. Unlike many, too many, Nelson Peery actually has lived a life worth writing about.

>via: http://thehnic.wordpress.com/2007/08/27/all-revolutionaries-aint-built-the-same/