JUNE JORDAN AND

A BLACK FEMINIST POETICS

OF ARCHITECTURE // SITE 1

This entry is the first by guest author A

lexis Pauline Gumbs, Phd. Alexis is a queer black troublemaker, a black feminist space cadet time-traveler and an inspired embodiment of love. She is the founder of the Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind Planetary Community School and the co-creator of the Mobile Homecoming Project: An Experiential Archive Amplifying Generations of Queer Black Brilliance.

Black women’s geographies and poetics challenge us to stay human by invoking how black spaces and places are integral to our planetary and local geographic stories and how the questions of seeable human differences puts spatial and philosophical demands on geography. These demands site the struggle between black women’s geographies and geographic domination, suggesting that more humanly workable geographies are continually being lived, expressed, and imagined.

-Katherine McKittrick in Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle

Site 1

The Bottom of the Barrel

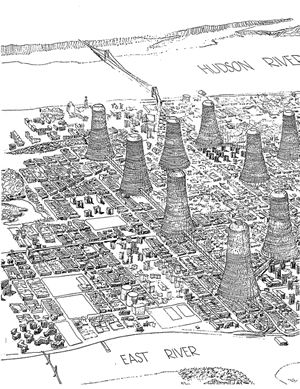

When June Jordan imagined “Skyrise for Harlem” the architectural plan that will be the model for this ritual of recitation and resituation, she was scraping the bottom of the barrel. After witnessing the Harlem riots in 1964, June Jordan abruptly found out that she was a newly single mother. She also offers frankly in a reflection in her first collection of essays, Civil Wars, “There was no money. Those days I didn’t eat.” Her son Christopher had to stay with her parents because she could not feed him. Sometimes friends dropped off milk and eggs and scotch and cigarettes. The money that she eventually got from selling her article about the architectural plan “Skyrise for Harlem” a plan in collaboration with her close friend R. Buckminster Fuller, was the only money that she had. On December 24th 1964 the money finally came and she was able to get Christopher back and assemple a semblance of Christmas. There was no money. Those days I did not eat. Some of June Jordan’s cousins have gone on record saying June Jordan was dramatic. She exaggerated. But I have seen the records of June Jordan’s phone getting cut off, I have seen the medical records that show the impact of poverty on her physical and psychological health. And knowing that for June Jordan who loved and admired her parents, but who also experienced abuse growing up in their home, I trust that it was really dire circumstances that had her make the difficult choice to send her son to live with her parents at this particularly dire economic time in her writing life.

This is important to state because for those of us who know anything about her June Jordan is a miracle. It is as if her life and her smile were sent out of the sky specifically to inspire us. She was a poet, skilled to create a language for living that contradicted the logic of global capitalism that institutionalized itself during her lifetime, but she was an architect because she built an ethical life out of difficult decisions everyday. Skyrise for Harlem, came from the very bottom of the barrel, the place where as womanist process theologian Monica Coleman and many others say, we make a way out of no way. Like Jordan’s tangible architectural work and blueprints, Jordan’s work as an architect, building something out of space filled by an empty belly is forgotten. As my partner Julia and I have travelled the country interviewing, honoring and documenting the work of innovated black queer feminist elders we have found that some of our genius elders have been couch surfing past middle age, face homelessness and worry daily about where they will house the priceless vessels of brilliance that are their bodies, and where they will keep the priceless boxes of archival materials they have saved from a life deciding to build something bigger than what capitalism would imply.

So the bottom of the barrel is a place, and I say it is a site of intervention. What does an architect who is accountable to the bottom of the barrel, who can give an account of what that rock and hard place space of choosing feels like, what does that architect imagine and build? And what happens to those plans in the context of capitalism? If you were to flip through the April 1965 issue of Esquire Magazine, the source of just in time money that allowed June Jordan to have Christopher home by Christmas, where June Jordan’s article and the plans for Skyrise for Harlem appear you would see the most expensive cars and liquor and clothing advertised. Not bottom of the barrel but top shelf, enticing the imagined audience of white men with disposable wealth. And maybe if you thought about the difference between the audience for these ads and the bottom of the barrel Harlem existence June Jordan was navigating as single mother you could predict but probably still never understand the violence of the editorial revisions the staff of Esquire made to her piece. June Jordan created a vision and an article called “Skyrise for Harlem” but here between the top-shelf scotch and the pall mall cigarettes and the newest Pontiac and the Italian leather shoes you will see a title June Jordan never approved, but consented to when she signed the paper that gave her the money to have Christopher home by Christmas. The bottom of the barrel. If you look you will see the title, not Skyrise for Harlem, but Instant Slum Clearance.

This instant. We were never meant to survive. Because that is what happens at the bottom of the barrel. You don’t get a say. But this triumph. On the bottom of the barrel what Katherine McKittrick calls a more humanly workable definition of life is being created. So visionary and transformative and dangerous to the unsustainable sponsors of Esquire magazine that it must be made into a joke. This is what happens at the bottom of the barrel the unglamorous and frightening space where housing is a basic need, where it is obvious how love and life and imagine suffer how home is impossible when whether you have water depends not on whether you go pump some, but on whether you can convince an absentee landlord to imagine you as human. June Jordan published a plan for Harlem generated from and accountable to the bottom of the barrel which is a place where we should not have to live, but is also an ethical space, a space of knowledge, a space of clarity about what life requires. So as architects of discourse and as builders of a movement, what do we know about the bottom of the barrel? How is that place of knowledge, clarity, injustice and violence reflected in our work? What everyday choices would we make if we were accountable to that place?

>via: http://pluraletantum.com/2012/03/21/june-jordan-and-a-black-feminist-poetics-of-architecture-site-1/

__________________________

June Jordan

1936–2002

One of the most widely-published and highly-acclaimed African American writers of her generation, poet, playwright and essayist June Jordan was also known for her fierce commitment to human rights and progressive political agenda. Over a career that produced twenty-seven volumes of poems, essays, libretti, and work for children, Jordan engaged the fundamental struggles of her era: over civil rights, women’s rights, and sexual freedom. A prolific writer across genres, Jordan’s poetry is known for its immediacy and accessibility as well as its interest in identity and the representation of personal, lived experience—her poetry is often deeply autobiographical; Jordan’s work can also be overtly political and often displays a radical, globalized notion of solidarity amongst the world’s marginalized and oppressed. In volumes like Some Changes (1971), Living Room (1985) and Talking Back to God (1997), Jordan uses conversational, often vernacular English to address topics ranging from family, bisexuality, political oppression, African American identity and racial inequality, and memory. Regarded as one of the key figures in the mid-century African American social, political and artistic milieu, Jordan also taught at many of the country’s most prestigious universities including Yale, State University of New York-Stony Brook, and the University of California-Berkley.

Born July 9, 1936, in Harlem, New York, Jordan had a difficult childhood and an especially fraught relationship with her father. Her parents were both Jamaican immigrants and, she recalled in Civil Wars: Selected Essays, 1963-80 (1981), “for a long while during childhood I was relatively small, short, and, in some other ways, a target for bully abuse. In fact, my father was the first regular bully in my life.” But Jordan also has positive memories of her childhood and it was during her early years that she began to write. Though becoming a poet “did not compute” for her parents, they did send the teen-aged Jordan to prep schools where she was the only black student. Her teachers encouraged her interest in poetry, but did not introduce her to the work of any black poets. After high school Jordan enrolled in Barnard College in New York City. Though she enjoyed some of her classes and admired many of the people she met, she felt fundamentally at odds with the predominately white, male curriculum and left Barnard without graduating.

In 1955, Jordan married Michael Meyer, a white Columbia University student. Interracial marriages faced considerable opposition at the time, and Jordan and her husband divorced after ten and a half years, leaving Jordan to support their son. At about the same time, Jordan’s career began to take off. First working in film, Jordan was soon exploring the impact of environment and architecture on the lives of low-income Black families, working with the architect Buckmeister Fuller. In 1966 she began teaching at the City College of the City University of New York, and in 1969 she published her first book of poetry, Who Look at Me. Aimed at young readers, the book was originally a project of Langston Hughes. Who Look at Me uses Black English poetry to describe several paintings of black Americans, prints of which are included in the book. Jordan felt strongly about the use of Black English, seeing it as a way to keep black community and culture alive. She encouraged black youngsters to write in that idiom through her writing workshops for black and Puerto Rican children. With Terri Bush, she edited a collection of her young pupils’ writings, The Voice of the Children; she also edited the enormously popular and influentialSoulscript: Afro-American Poetry (1970; reprinted 2004).

Jordan’s concern for children, especially African-American children, always stood out in her work. Her 1971 novel for young adults, His Own Where, also written in Black English, explores Jordan’s interests in environmental design. Sixteen-year-old Buddy, and his younger girlfriend, Angela, try to create a world of their own in an abandoned house near a cemetery. Jordan explained her feelings about the book to De Veaux: “Buddy acts, he moves. He is the man I believe in, the man who will come to lead his people into a new community.” Jordan’s other work for young people includes Dry Victories (1972), New Life: New Room (1975), and Kimako’s Story (1981), inspired by the young daughter of Jordan’s friend, fellow writer Alice Walker.

Although Jordan has not written specifically for young readers since Kimako’s Story, she explores her own formative years in Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood (2000). Jordan’s searing description of learning to be a “good little soldier” under the severe tutelage of her father who drove her to be strong and smart, to appreciate beauty, but often at the cost of a beating, is told in the guileless voice of a child. Jordan explained her goal for the book in an interview with Elizabeth Farnsworth of NewsHour: “I wanted to honor my father, first of all, and secondly, I wanted people to pay attention to a little girl who is gifted intellectually and creative, and to see that there’s a complexity here that we may otherwise not be prepared to acknowledge or even search for, let alone encourage, and to understand that this is an okay story…a story, I think, with a happy outcome.” Jordan further commented in an Essence interview: “My father was very intense, passionate and over-the-top. He was my hero and my tyrant.” Booklist critic Stephanie Zvirin observed that Soldier, written “in the flowing language of a prose poem” is “a haunting coming-of-age memoir.”

Throughout her long career, Jordan gained considerable renown as both an essayist and political writer, penning a regular column for the Progressive. In Some of Us Did Not Die: New and Selected Essays of June Jordan (2002), published the same year of the author’s death from breast cancer, Jordan presents thirty-two previously published essays as well as eight new tracts. The essays examine a wide range of topics, from sexism, racism, and Black English to trips the author made to various places, the decline of the U.S. educational system, and the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001. Writing for Lambda Book Report, Samiya A. Bashir called the new essays “fiery,” adding that the collection provides “evidence of…[Jordan’s] indomitable spirit.” Noting that Jordan writes about homosexuality as well as her own bisexuality, Bashir went on, “In the essay, ‘A Couple of Words on Behalf of Sex (Itself),’ Jordan moved beyond the ethereal beauty of love in defense of the concrete beauty of sexual experience and desire. In typically humorous style she decried the increasing demonization of sexuality and sexual desire.” A Kirkus Reviews contributor wrote, “Some of the stronger pieces here…address the vast complex of injustice that is contemporary American life.” An edition of Jordan’s collected poems was also published posthumously. That volume, Directed by Desire: The Collected Poems of June Jordan (2005), includes various poems published from 1969 through 2001, many of which discuss her battle with cancer. Janet St. John, writing in Booklist, declared the book “a must-read for those wanting to learn and be transformed by Jordan’s opinions and impressions.”

In an obituary for the San Francisco Chronicle, Annie Nakao wrote that the author “left a mountain of literary and political works.” Nakao added: “As I discovered soon enough when I picked up a June Jordan work, its contents could shout, caress, enrage. The thing it never did was leave you unengaged.” In an article of appreciation in the Los Angeles Times following the author’s death, Lynell George explained how the author “spent her life stitching together the personal and political so the seams didn’t show.” George further stated that throughout her life the author “continued to publish across the map, swinging form to form as the occasion or topic demanded. Through poetry, essays, plays, journalism, even children’s literature, she engaged such topics as race, class, sexuality, capitalism, single motherhood and liberation struggles around the globe.” However, Jordan perhaps understood her own legacy best. In an interview with Alternative Radio before her death, Jordan was asked about the role of the poet in society. Jordan replied: “The role of the poet, beginning with my own childhood experience, is to deserve the trust of people who know that what you do is work with words.” She continued: “Always to be as honest as possible and to be as careful about the trust invested in you as you possibly can. Then the task of a poet of color, a black poet, as a people hated and despised, is to rally the spirit of your folks…I have to get myself together and figure out an angle, a perspective, that is an offering, that other folks can use to pick themselves up, to rally and to continue or, even better, to jump higher, to reach more extensively in solidarity with even more varieties of people to accomplish something. I feel that it’s a spirit task.”

CAREER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- (Editor) Soulscript: Afro-American Poetry (anthology), Doubleday (Garden City, NY), 1970.

- Some Changes, Dutton (New York, NY), 1971.

- Poem: On Moral Leadership as a Political Dilemma (Watergate, 1973), Broadside Press (Detroit, MI), 1973.

- New Days: Poems of Exile and Return, Emerson Hall (New York, NY), 1973.

- Things That I Do in the Dark: Selected Poetry, Random House (New York, NY), 1977, revised edition, Beacon Press (Boston, MA), 1981.

- Passion: New Poems, 1977-1980, Beacon Press (Boston, MA), 1980.

- Living Room: New Poems, 1980-1984, Thunder’s Mouth Press (New York, NY), 1985.

- High Tide—Marea Alta, Curbstone Press (Willimantic, CT), 1987.

- Lyrical Campaigns: Selected Poems, Virago Press (London, England), 1989.

- Naming Our Destiny: New and Selected Poems, Thunder’s Mouth Press (New York, NY), 1989.

- Haruko/Love Poetry: New and Selected Love Poems, Virago Press (London, England), 1993, published asHaruko: Love Poems, High Risk Books (New York, NY), 1994.

- Kissing God Good-Bye: New Poems, 1991-1997, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1997.

- (Editor) Soulscript: A Collection of African American Poetry, Harlem Moon (New York, NY), 2004.

- Directed by Desire: The Collected Poems of June Jordan, edited by Jan Heller Levi and Sara Miles, Copper Canyon Press (Port Townsend, WA), 2005.

FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS

- Who Look at Me (poetry; for young adults), Crowell (New York, NY), 1969.

- (Editor, with Terri Bush) The Voice of the Children (poetry anthology; for young adults), Holt (New York, NY), 1970.

- His Own Where (young adult novel), Crowell (New York, NY), 1971.

- Dry Victories (nonfiction; for young adults), Holt (New York, NY), 1972.

- Fannie Lou Hamer (biography; for young adults), illustrated by Albert Williams, Crowell (New York, NY), 1972.

- New Life: New Room (picture book), illustrated by Ray Cruz, Crowell (New York, NY), 1975.

- Kimako’s Story (picture book), illustrated by Kay Burford, Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1981.

PLAYS

- In the Spirit of Sojourner Truth, produced at Public Theatre, New York, NY, May, 1979.

- For the Arrow that Flies by Day (staged reading), produced at the Shakespeare Festival, New York, NY, April, 1981.

- Freedom Now Suite, music by Adrienne B. Torf, produced in New York, NY, 1984.

- The Break, music by Adrienne B. Torf, produced in New York, NY, 1984.

- The Music of Poetry and the Poetry of Music, music by Adrienne B. Torf, produced in New York, NY, and Washington, DC, 1984.

- Bang Bang über Alles, music by Adrienne B. Torf, produced in Atlanta, GA, 1986.

- I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky (opera libretto; music by John Adams; produced at Lincoln Center, New York, NY), Scribner (New York, NY), 1995.

NONFICTION

- Civil Wars: Selected Essays, 1963-80 (autobiographical essays), Beacon Press (Boston, MA), 1981, revised edition, Scribner (New York, NY), 1996.

- On Call: Political Essays, 1981-1985, South End Press (Boston, MA), 1985.

- Bobo Goetz a Gun, Curbstone Press (Willimantic, CT), 1985.

- Moving towards Home: Political Essays, Virago Press (London, England), 1989.

- Technical Difficulties: African American Notes on the State of the Union, Pantheon Books (New York, NY), 1992.

- Affirmative Acts: Political Essays, Anchor Books (New York, NY), 1998.

- Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood (memoir), Basic Books (New York, NY), 2000.

- Some of Us Did Not Die: New and Selected Essays of June Jordan, Basic/Civitas Books (New York, NY), 2002.

OTHER

- Also author of The Issue. Work represented in numerous anthologies, including Double Stitch: Black Women Write about Mothers and Daughters, edited by Patricia Bell-Scott, Harper, 1992. Contributor of stories and poems (prior to 1969 under name June Meyer) to national periodicals, including Esquire, Nation, Evergreen, Partisan Review, Negro Digest, Harper’s Bazaar, Library Journal, Encore, Freedomways, New Republic, Ms., American Dialog, New Black Poetry, Black World, Black Creation, Essence, and to newspapers, including Village Voice, New York Times, and New York Times Magazine. Author of column “The Black Poet Speaks of Poetry,” American Poetry Review, 1974-77; regular columnist for the Progressive, 1989-97; contributing editor for Chrysalis, First World and Hoo Doo.

FURTHER READING

- American Women Writers, 2nd edition, St. James Press (Detroit, MI), 2000.

- Children’s Literature Review, Volume 10, Thomson Gale (Detroit, MI), 1986.

- Contemporary Literary Criticism, Volume 114, Thomson Gale (Detroit, MI), 1999.

- Contemporary Poets, 7th edition, St. James Press (Detroit, MI), 2001.

- Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 38: Afro-American Writers after 1955: Dramatists and Prose Writers, Thomson Gale (Detroit, MI), 1985.

- Jordan, June, Civil Wars: Selected Essays, 1963-80, revised edition, Scribner (New York, NY), 1996.

- Jordan, June, Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood, Basic Books (New York, NY), 2000.

- Muller, Lauren, editor, June Jordan’s Poetry for the People: A Revolutionary Blueprint, Routledge (New York, NY), 1995.

- St. James Guide to Young Adult Writers, 2nd edition, St. James Press (Detroit, MI), 1999.

PERIODICALS

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 7, 2000, Valerie Boyd, review of Soldier, p. L15.

- Austin Chronicle, August 25, 2000, Craig Arnold, review of Soldier.

- Black Issues Book Review, September, 2000, Samiya A. Bashir, review of Soldier, p. 32.

- Booklist, February 15, 2001, Donna Seaman, review of Kissing God Goodbye: Poems 1991-96, p. 1102; April 1, 2001, Stephanie Zvirin, review of Soldier, p. 1461; September 1, 2005, Janet St. John, review of Directed by Desire: The Collected Poems of June Jordan, p. 43.

- ColorLines, winter, 1999, Julie Quiroz, “‘Poetry Is a Political Act’: An Interview with June Jordan.”

- Essence, April, 1981, Alexis De Veaux, “Creating Soul Food: June Jordan”; September, 2000, Alexis De Veaux, “A Conversation with June Jordan,” p. 102.

- Kirkus Reviews, July 1, 2002, review of Some of Us Did Not Die: New and Selected Essays of June Jordan, p. 933.

- Lambda Book Report, October, 2002, Samiya A. Bashir, review of Some of Us Did Not Die, p. 28.

- Library Journal, October 1, 2004, Michael Rogers, review of Soulscript: A Collection of African American Poetry, p. 121.

- Los Angeles Times, May 15, 2000, Merle Rubin, review of Soldier, p. E3; June 20, 2002, Lynell George, “An Appreciation: A Writer Intent on Rallying the Spirit of Survival; Poet June Jordan Cast a Penetrating Eye on Issues Both Political and Personal,” p. E1.

- Ms., June-July, 2000, R. Erica Doyle, review of Soldier, p. 82.

- New York Times, July 4, 2000, Felicia R. Lee, “A Feminist Survivor with the Eyes of a Child,” review of Soldier, p. B1.

- Publishers Weekly, May 8, 2000, review of Soldier, p. 218; July 8, 2002, review of Some of Us Did Not Die, p. 42; June 27, 2005, review of Directed by Desire, p. 54.

ONLINE

- Alternative Radio, http://www.alternativeradio.org/ (March 24, 2006), David Barsamian, “June Jordan: Childhood Memories, Poetry & Palestine.”

- June Jordan Home Page, http://junejordan.com (March 24, 2006).

- Online NewsHour,http://www.pbs.org/newshour/ (March 26, 2006), Elizabeth Farnsworth, “A Conversation with June Jordan.”

PERIODICALS

- Guardian (London, England), June 20, 2002, p. 20.

- Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2002, p. B19.

- New York Times, June 18, 2002, p. A23.

- San Francisco Chronicle, June 27, 2002, Annie Nakao, “June Jordan—in Your Face and in Our Hearts,” p. D12.

- Washington Post, June 16, 2002, p. C8.

Discover this poet’s context and related poetry, articles, and media.