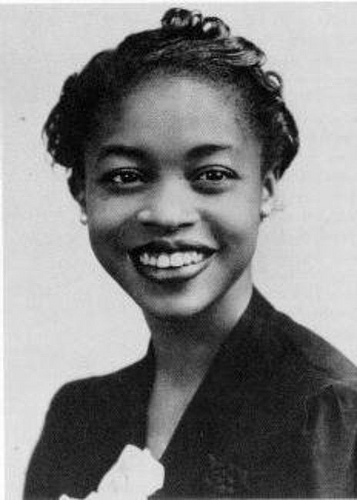

Margaret Walker

1915–1998

(Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage)

(July 7, 1915 in Birmingham, Alabama – November 30, 1998)

When For My People by Margaret Walker won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award in 1942, “she became one of the youngest Black writers ever to have published a volume of poetry in this century,” as well as “the first Black woman in American literary history to be so honored in a prestigious national competition,” noted Richard K. Barksdale in Black American Poets between Worlds, 1940-1960. Walker’s first novel, Jubilee, is notable for being “the first truly historical black American novel,” reported Washington Post contributor Crispin Y. Campbell. It was also the first work by a black writer to speak out for the liberation of the black woman. The cornerstones of a literature that affirms the African folk roots of black American life, these two books have also been called visionary for looking toward a new cultural unity for black Americans that will be built on that foundation.

The title of Walker’s first book, For My People, denotes the subject matter of “poems in which the body and spirit of a great group of people are revealed with vigor and undeviating integrity,” wrote Louis Untermeyer in the Yale Review. Here, in long ballads, Walker draws sympathetic portraits of characters such as the New Orleans sorceress Molly Means; Kissie Lee, a tough young woman who dies “with her boots on switching blades”; and Poppa Chicken, an urban drug dealer and pimp. Other ballads give a new dignity to John Henry, killed by a ten-pound hammer, and Stagolee, who kills a white officer but eludes a lynch mob. In an essay for Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation, Eugenia Collier noted, “Using … the language of the grass-roots people, Walker spins yarns of folk heroes and heroines: those who, faced with the terrible obstacles which haunt Black people’s very existence, not only survive but prevail–with style.” Soon after it appeared, the book of ballads, sonnets, and free verse found a surprisingly large number of readers, requiring publishers to authorize three printings to satisfy popular demand.

“If the test of a great poem is the universality of statement, then ‘For My People‘ is a great poem,” remarked Barksdale. The critic explained in Donald B. Gibson’s Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays that the poem was written when “world-wide pain, sorrow, and affliction were tangibly evident, and few could isolate the Black man’s dilemma from humanity’s dilemma during the depression years or during the war years.” Thus, the power of resilience presented in the poem is a hope Walker holds out not only to black people, but to all people, to “all the Adams and Eves.” As she once remarked, “Writers should not write exclusively for black or white audiences, but most inclusively. After all, it is the business of all writers to write about the human condition, and all humanity must be involved in both the writing and in the reading.”

Jubilee, a historical novel, is the second book on which Walker’s literary reputation rests. It is the story of a slave family during and after the Civil War, and it took her thirty years to write. During these years, she married a disabled veteran, raised four children, taught full time at Jackson State College in Mississippi, and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. The lengthy gestation, she believes, partly accounts for the book’s quality. As she told Claudia Tate in Black Women Writers at Work,“Living with the book over a long period of time was agonizing. Despite all of that,Jubilee is the product of a mature person,” one whose own difficult pregnancies and economic struggles could lend authenticity to the lives of her characters. “There’s a difference between writing about something and living through it,” she said in the interview; “I did both.”

The story of Jubilee‘s main characters Vyry and Randall Ware was an important part of Walker’s life even before she began to write it down. As she explains in How I Wrote “Jubilee,” she first heard about the “slavery time” in bedtime stories told by her maternal grandmother. When old enough to recognize the value of her family history, Walker took initiative, “prodding” her grandmother for more details, and promising to set down on paper the story that had taken shape in her mind. Later on, she completed extensive research on every aspect of the black experience touching the Civil War, from obscure birth records to information on the history of tin cans. “Most of my life I have been involved with writing this story about my great-grandmother, and even if Jubilee were never considered an artistic or commercial success I would still be happy just to have finished it,” she claims.

Soon after Jubilee was published in 1966, Walker was given a fellowship award from Houghton Mifflin. Granting that the novel is “ambitious,” New York Times Book Review contributor Wilma Dykeman deemed it “uneven.” Arthur P. Davis, writing inFrom the Dark Tower: Afro-American Writers, 1900-1960, suggested that the author “has crowded too much into her novel.” On the other hand, Abraham Chapman of theSaturday Review appreciated the author’s “fidelity to fact and detail” as she “presents the little-known everyday life of the slaves,” their music, and their folkways. In the Christian Science Monitor, Henrietta Buckmaster commented, “In Vyry, Miss Walker has found a remarkable woman who suffered one outrage after the other and yet emerged with a humility and a mortal fortitude that reflected a spiritual wholeness.” Dykeman felt that, “In its best episodes, and in Vyry, ‘Jubilee’ chronicles the triumph of a free spirit over many kinds of bondages.” Later critical studies of the book emphasize the importance of its themes and its position as the prototype for novels that present black history from a black perspective. Roger Whitlow claimed in Black American Literature: A Critical History, “It serves especially well as a response to white ‘nostalgia’ fiction about the antebellum and Reconstruction South.”

Walker’s next book to be highly acclaimed was Prophets for a New Day, a slim volume of poems. Unlike the poems in For My People, which, in a Marxist fashion, names religion an enemy of revolution, remarked Collier, Prophets for a New Day“reflects a profound religious faith. The heroes of the sixties are named for the prophets of the Bible: Martin Luther King is Amos, Medgar Evars is Micah, and so on. The people and events of the sixties are paralleled with Biblical characters and occurrences. . . . The religious references are important. Whether one espouses the Christianity in which they are couched is not the issue. For the fact is that Black people from ancient Africa to now have always been a spiritual people, believing in an existence beyond the flesh.” One poem in Prophets that harks back to African spiritism is “Ballad of Hoppy Toad” with its hexes that turn a murderous conjurer into a toad. Though Collier felt that Walker’s “vision of the African past is fairly dim and romantic,” the critic went on to say that this poetry “emanates from a deeper area of the psyche, one which touches the mythic area of a collective being and reenacts the rituals which define a Black collective self.” Perhaps more importantly, in all the poems, observed Collier, Walker depicts “a people striking back at oppression and emerging triumphant.”

Much of Walker’s responsiveness to the black experience, communicated through the realism of her work, can be attributed to her growing up in a southern home environment that emphasized the rich heritage of black culture. Walker was born on July 7, 1915, in Birmingham, Alabama, to the Reverend Sigismund C. Walker and Marion Dozier Walker. The family moved to New Orleans when Walker was a young child. A Methodist minister who had been born near Buff Bay, Jamaica, Walker’s father was a scholar who bequeathed to his daughter his love of literature–the classics, the Bible, Benedict de Spinoza, Arthur Schopenhauer, the English classics, and poetry. Similarly, Walker’s musician mother played ragtime and read poetry to her, choosing among such varied authors and works as Paul Laurence Dunbar, John Greenleaf Whittier‘s “Snowbound,” the Bible, and Shakespeare. At age eleven Walker began reading the poetry of Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Elvira Ware Dozier, her maternal grandmother, who lived with her family, told Walker stories, including the story of her own mother, a former slave in Georgia. Before she finished college at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, in the early 1930s, Walker had heard James Weldon Johnson read from God’s Trombones (1927), listened to Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes sing in New Orleans, and, in 1932, heard Hughes read his poetry in a lecture recital at New Orleans University, where her parents then taught. She met Hughes in 1932, and he encouraged her to continue writing poetry. Her first poem was published in Crisis in 1934.

As a senior at Northwestern in 1934, Walker began a fruitful association with the Works Progress Administration (WPA). She lived on Chicago’s North Side and worked as a volunteer on the WPA recreation project. The project directors assigned her to associate with so-called delinquent girls, mainly shoplifters and prostitutes, in order to determine if Walker’s different background and training might have a positive influence on them. She became so fascinated by an Italian-black neighborhood that she eventually chose it as the setting and title for a novel that she began writing (but never published), Goose Island. On Friday, March 13, 1936, Walker received notice to report to the WPA Writer’s Project in Chicago as a full-time employee. Classified as a junior writer–her salary was eighty-five dollars a month–her work assignment was the Illinois Guide Book. Other writers on the project were Nelson Algren, Jacob Scher, James Phelan, Sam Ross, Katherine Dunham, Willard Motley, Frank Yerby, Fenton Johnson, and Richard Wright. In 1937 the WPA office allowed her to come into the downtown quarters only twice weekly so that she might remain at home working on her novel.

Perhaps her most rewarding interaction with a writer at the project was Walker’s friendship with Wright, a liaison that, while it lasted, proved practical and beneficial to both fledgling writers. Before she joined the project, Walker had met Wright in Chicago in February, 1936, when he had presided at the writer’s section of the first National Negro Congress. Walker had attended solely to meet Hughes again, to show him the poetry she had written since their first meeting four years earlier. Hughes refused to take her only copy of the poems, but he introduced her to Wright and insisted that he include Walker if a writer’s group organized. Wright then introduced her to Arna Bontemps and Sterling A. Brown, also writers with the WPA.

Although Wright left Chicago for New York at the end of May, neither his friendship with Walker nor their literary interdependence ended immediately. Walker provided him, in fact, with important help on Native Son (1940), mailing him–as he requested–newspaper clippings about Robert Nixon, a young black man accused of rape in Chicago, and assisting Wright in locating a vacant lot to use as the Dalton house address when Wright returned to Chicago briefly the next year. Furthermore, Walker was instrumental in acquiring for him a copy of the brief of Nixon’s case from attorney Ulysses S. Keyes, the first black lawyer hired for the case. Together, Wright and Walker visited Cook County jail, where Nixon was incarcerated, and the library, where on her library card they checked out a book on Clarence Darrow and two books on the Loeb-Leopold case, from which, in part, Wright modeled Bigger’s defense when he completed his novel in the spring of 1939.

Walker began teaching in the 1940s. She taught at North Carolina’s Livingstone College in 1941 and West Virginia State College in 1942. In 1943 she married Firnist James Alexander. In that year, too, she began to read her poetry publicly when she was invited by Arthur P. Davis to read “For My People” at Richmond’s Virginia Union University, where he was then teaching. After the birth of the first of her four children in 1944, Walker returned to teach at Livingstone for a year. She also resumed the research on her Civil War novel in the 1940s. She began with a trip to the Schomburg Center in 1942. In 1944 she received a Rosenwald fellowship to further her research. In 1948 Walker was unemployed, living in High Point, North Carolina, and working on the novel. By then she clearly envisioned the development of Jubilee as a folk novel and prepared an outline of incidents and chapter headings, the latter which were supplied by the stories of her grandmother. In 1949 Walker moved to Jackson, Mississippi, and began her long teaching career at Jackson State College (now Jackson State University).

The fictional history of Walker’s great-grandmother, here called Vyry, Jubilee is divided into three sections: the antebellum years in Georgia on John Dutton’s plantation, the Civil War years, and the Reconstruction era. Against a panoramic view of history Walker focuses the plot specifically on Vyry’s life as she grows from a little girl to adulthood. In the first section Vyry, the slave, matures, marries and separates from Randall Ware, attempts to escape from slavery with her two children, and is flogged. The second section emphasizes the destruction of war and the upheaval for slaveowner and slaves, while the last section focuses on Vyry as a displaced former slave, searching for a home.

Walker said her research was done “to undergird the oral tradition,” and Jubilee is primarily known for its realistic depiction of the daily life and folklore of the black slave community. Although there are also quotes from Whittier and the English romantic poets, she emphasizes the importance of the folk structure of her novel by prefacing each of the fifty-eight chapters with proverbial folk sayings or lines excerpted from spirituals. The narrative is laced with verses of songs sung by Vyry, her guardian, or other slaves. A portion from a sermon is included. The rhymes of slave children are also a part of the narrative. A conjuring episode is told involving the overseer Grimes, suggesting how some folk beliefs were used for protection. Vyry provides a catalogue of herbs and discusses their medicinal and culinary purposes.

In response to Walker’s Civil War story, Guy Davenport commented in National Review that “the novel from end to end is about a place and a people who never existed.” For him Walker had merely recalled all the elements of the southern myth, writing a lot of “tushery that comes out of books, out of Yerby and Margaret Mitchell.” He further found “something deeply ironic in a Negro’s underwriting the made-up South of the romances, agreeing to every convention of the trade.” More justly, Chapman in the Saturday Review found “a fidelity to fact and detail” in the depictions of slave life that was better than anything done before. Lester Davis, a contributor to Freedomways, decided that one could overlook the “sometimes trite and often stilted prose style” because the novel is “a good forthright treatment of a segment of American history about which there has been much hypocrisy and deliberate distortion.” He found the “flavor of authenticity … convincing and refreshing. ”

Walker’s How I Wrote “Jubilee,” a history of the novel’s development from her grandmother’s oral history, is an indirect response to those critics who comparedJubilee with books like Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936) and who accused Walker of sustaining the southern myth from the black perspective. She answers her detractors by citing the references and historical documents she perused over several years in order to gird her oral story with historical fact.

Walker’s volume of poetry Prophets for a New Day was published in 1970. She calledProphets for a New Day her civil rights poems, and only two poems in the volume, “Elegy” and “Ballad of the Hoppy Toad,” are not about the civil rights movement. Walker begins the volume with two poems in which the speakers are young children; one eight-year-old demonstrator eagerly waits to be arrested with her group in the fight for equality, and a second one is already jailed and wants no bail. Her point is that these young girls are just as much prophets for a new day as were Nat Turner, Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and John Brown. In “The Ballad of the Free” Walker establishes a biblical allusion and association as an integral part of the fight to end racism: “The serpent is loosed and the hour is come / The last shall be first and the first shall be none / The serpent is loosed and the hour is come.”

The title poem, “Prophets for a New Day,” and the seven poems that follow it invite obvious comparisons between the biblical prophets and the black leaders who denounced racial injustice and prophesied change during the civil rights struggle of the 1960s. For example, several prophets are linked to specific southern cities marked by racial turmoil: in “Jeremiah,” the first poem of the series, Jeremiah “is now a man whose names is Benjamin / Brooding over a city called Atlanta / Preaching the doom of a curse upon the land.” Among the poems, other prophets mentioned include “Isaiah,” “Amos,” and “Micah,” a poem subtitled “To the memory of Medgar Evers of Mississippi.”

In For My People Walker urged that activity replace complacency, but in Prophets for a New Day she applauds the new day of freedom for black people, focusing on the events, sites, and people of the struggle. Among the poems that recognize southern cities associated with racial turbulence are “Oxford Is a Legend,” “Birmingham,” “Jackson, Mississippi,” and “Sit-Ins.” Of these, the latter two, claim reviewers, are the most accomplished pieces. “Sit-Ins” is a recognition of “those first bright young to fling their … names across pages / Of new Southern history / With courage and faith, convictions, and intelligence.”

CAREER

Worked as a social worker, newspaper reporter, and magazine editor; Livingstone College, Salisbury, NC, member of faculty, 1941-42; West Virginia State College, Institute, WV, instructor in English, 1942-43; Livingstone College, professor of English, 1945-46; Jackson State College, Jackson, MS, professor beginning 1949, professor emeritus of English, director of Institute for the Study of the History, Life, and Culture of Black Peoples, 1968–. Lecturer, National Concert and Artists Corp. Lecture Bureau, 1943-48. Visiting professor in creative writing, Northwestern University, spring, 1969. Staff member, Cape Cod Writers Conference, Craigville, MA, 1967 and 1969. Participant, Library of Congress Conference on the Teaching of Creative Writing, 1973.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

POETRY

- For My People, Yale University Press (New Haven, CT), 1942.

- Ballad of the Free, Broadside Press (Detroit, MI), 1966.

- Prophets for a New Day, Broadside Press (Detroit, MI), 1970.

- October Journey, Broadside Press (Detroit, MI), 1973.

- This Is My Century, University of Georgia Press (Athens, GA), 1989.

PROSE

- Jubilee (novel), Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1965.

- How I Wrote “Jubilee,” Third World Press (Chicago, IL), 1972.

- (With Nikki Giovanni) A Poetic Equation: Conversations between Nikki Giovanni and Margaret Walker, Howard University Press (Washington, DC), 1974.

- Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius, Dodd (New York, NY), 1987.

- How I Wrote Jubilee and Other Essays on Life and Literature, edited by Maryemma Graham, Feminist Press at The City University of New York (New York, NY), 1990.

- On Being Female, Black, and Free: Essays by Margaret Walker, 1932-1992, University of Tennessee Press (Knoxville, TN), 1997.

- Conversations with Margaret Walker, edited by Maryemma Graham, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson, MI), 2002.

OTHER

- Contributor to Black Expression, edited by Addison Gayle, Weybright & Tally (New York, NY), 1969; Many Shades of Black, edited by Stanton L. Wormley and Lewis H. Fenderson, Morrow (New York, NY), 1969; Stephen Henderson’s Understanding the New Black Poetry: Black Speech and Black Music as Poetic References, Morrow (New York, NY), 1973, and The Furious Flowering of African American Poetry, edited by Joanne V. Gabbin, University Press of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA), 1999.

- Also contributor to numerous anthologies, including Adoff’s Black Out Loud, Weisman and Wright’s Black Poetry for All Americans, and Williams’ Beyond the Angry Black. Contributor of articles to periodicals includingMississippi Folklore Register and Southern Quarterly.

FURTHER READING

BOOKS

- African American Writers, Gale (Detroit, MI), 2nd edition, 2000, volume 2, pp. 759-771.

- Bankier, Joanna, and Dierdre Lashgari, editors, Women Poets of the World, Macmillan (New York, NY), 1983.

- Baraka, Amiri, The Black Nation, Getting Together Publications, 1982.

- Contemporary Literary Criticism, Gale (Detroit, MI), Volume 1, 1973; Volume 2, 1976.

- Contemporary Southern Writers, St. James Press (Detroit, MI), 1999.

- Davis, Arthur P., From the Dark Tower: Afro-American Writers, 1900 to 1960, Howard University Press (Washington, DC), 1974.

- Emanuel, James A., and Theodore L. Gross, editors, Dark Symphony: Negro Literature in America, Free Press (New York, NY), 1968.

- Evans, Mari, editor, Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation, Anchor/Doubleday (New York, NY), 1982.

- Gayle, Addison, editor, The Black Aesthetic, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1971.

- Gibson, Donald B., editor, Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays, Prentice-Hall (Englewood Cliffs, NJ), 1983.

- Henderson, Ashyia, editor, Contemporary Black Biography, Volume 29, Gale (Detroit, MI), 2001.

- Jackson, Blyden, and Louis D. Rubin Jr., Black Poetry in America: Two Essays in Historical Interpretation,Louisiana State University Press (Baton Rouge, LA), 1974.

- Jones, John Griffith, in Mississippi Writers Talking, Volume II, University of Mississippi Press (Jackson, MS), 1983.

- Kent, George E., Blackness and the Adventure of Western Culture, Third World Press (Chicago, IL), 1972.

- Lee, Don L., Dynamite Voices I: Black Poets of the 1960s, Broadside Press (Detroit, MI), 1971.

- Miller, R. Baxter, editor, Black American Poets between Worlds, 1940-1960, University of Tennessee Press (Knoxville, TN), 1986.

- Mitchell, Angelyn, editor, Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present, Duke University Press (Durham, NC), 1994.

- Modern Black Writers, Gale (Detroit, MI), 2nd edition, 1999, pp. 758-762.

- Pryse, Marjorie, and Hortense J. Spillers, editors, Conjuring: Black Women, Fiction, and Literary Tradition,Indiana University Press (Bloomington, IN), 1985.

- Redmond, Eugene B., Drumvoices: The Mission of Afro-American Poetry-A Critical Evaluation, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1976.

- Tate, Claudia, editor, Black Women Writers at Work, Continuum, 1983.

- Walker, Margaret, How I Wrote “Jubilee,” Third World Press (Chicago, IL), 1972.

- Whitlow, Roger, Black American Literature: A Critical History, Nelson Hall, 1973.

PERIODICALS

- African American Review, summer, 1993, Jerry W. Ward Jr., “Black South Literature: Before Day Annotations (for Blyden Jackson),” p. 315.

- Atlantic Monthly, December, 1942.

- Black World, December, 1971; December, 1975.

- Booklist, July, 1997, Alice Joyce, review of On Being Female, Black, and Free: Essays by Margaret Walker, 1932-1992, p. 1794; February 15, 1998, Brad Hooper, review of Jubilee, p. 979.

- Book Week, October 2, 1966.

- Callaloo, May, 1979.

- Christian Science Monitor, November 14, 1942; September 29, 1966; June 19, 1974; January 22, 1990, Laurel Shaper, “One woman’s world of words; ‘Jubilee’ author draws on her racial experience to craft works of concern and compassion”.

- CLA Journal, December, 1977.

- Ebony, February, 1949.

- Freedomways, summer, 1967.

- Library Journal, November 1, 1989, Fred Muratori, review of This Is My Century: New and Collected Poems, p. 92; January 1990, Molly Brodsky, review of Jubilee and Other Essays on Life and Literature, p. 110; June 15, 1997, Ann Burns, review of On Being Female, Black, and Free: Essays by Margaret Walker, 1932-1992, p. 69.

- Mississippi Quarterly, fall, 1988; fall, 1989.

- National Review, October 4, 1966.

- Negro Digest, February, 1967; January, 1968.

- New Republic, November 23, 1942.

- New York Times, November 4, 1942.

- New York Times Book Review, August 2, 1942; September 25, 1966.

- Publishers Weekly, April 15, 1944; March 24, 1945.

- Saturday Review, September 24, 1966.

- Times Literary Supplement, June 29, 1967.

- Washington Post, February 9, 1983.

- Yale Review, winter, 1943.

ONLINE

- Internet Poetry Archive, http://www.ibiblio.org/ipa/walker/ (October 24, 2003).

- Modern American Poetry, http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/ (October 27, 2003).

- University of Mississippi, http://www.olemiss.edu/ (April 17, 2003), Jon Tucker, “Margaret Walker Alexander.”

- Voices from the Gaps, Women Writers of Color, http://voices.cla.umn.edu/ (December 9, 1999), Danye A. Pelichet, Shanese Baylor, and Kinitra D. Brooks, “Dr. Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander.”

OBITUARIES

- African American Review, spring, 1999, p. 5.

- Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1998, p. 8.

- Current Biography, June, 1999, p. 62.

- Los Angeles Times, December 2, 1998, p. A24.

- New York Times, December 4, 1998, p. A29.

- Washington Post, December 1, 1998, p. B6.

>via: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/margaret-walker