Published: May 31, 2013

William Demby, Author of Experimental Novels, Dies at 90

By WILLIAM YARDLEY

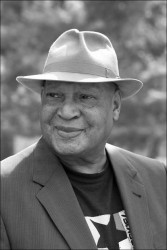

William Demby, whose novels, written while he was an expatriate in Italy, challenged literary conventions and expectations of what a black writer should write about, died on May 23 at his home in Sag Harbor, N.Y. He was 90.

His wife, Barbara Morris, confirmed the death.

Mr. Demby was interested in boundaries — between people, and between the present and the past — and he liked crossing them. His marriage in 1953 to an Italian actress and writer, Lucia Drudi, made news in Rome. (He spent many years writing English-language subtitles for films by Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini and other Italian directors.)

His first novel, “Beetlecreek,” published in 1950 while he was living in Italy, described the unexpected relationships that develop among a reclusive white man, a black teenage boy and others in a small Southern town. Some critics called the book disjointed, but many praised Mr. Demby for the depth of his characters.

Mr. Demby, who lived outside Florence in a villa his wife had inherited, spent the next several years writing freelance magazine articles as well as doing film translation work while working on his second novel.

That novel, “The Catacombs,” was published 15 years after “Beetlecreek.” It was an experimental blend of fiction and nonfiction in which one of the main characters, a man named Bill Demby, writes a book about a black actress named Doris who grows weary of him. The narrative, interspersed with newspaper clippings, philosophical detours and stream-of-consciousness observations, confounded some critics.

“Impatience sets in for this reader as much as it does for poor Doris,” Peter Buitenhuis wrote in a review in The New York Times in 1965.

But others were impressed, and some said Mr. Demby was criticized in part because he did not focus primarily on racial issues. The critic Robert Bone, writing in The Times in 1969, called “The Catacombs” “one of the two important black novels of the 1960s,” along with “The Chosen Place, the Timeless People,” by Paule Marshall.

James C. Hall, who teaches history and literature at the University of Alabama, interviewed Mr. Demby extensively in the 1990s for “Mercy, Mercy Me,” his book about efforts by black artists of the 1960s to reach beyond race.

“A lot of the complaints about it were that it didn’t seem sufficiently black,” Mr. Hall said of the reaction to “The Catacombs” in a recent interview.

“There’s no question that ‘Catacombs’ was really ambitious,” he added. “He did not want to speak of racial justice in a direct way. But you could make the argument it did, by defending the right of the African-American artist to choose whatever subject matter and to choose whatever method he or she thought was most appropriate.”

In a 2004 interview with The Bloomsbury Review, Mr. Demby said, “Since ‘Catacombs,’ I think I have been kicked out of the Black Arts race.”

He kept writing. In 1978 he published “Love Story Black,” about an unlikely romance between an elderly woman and a much younger man. In the mid-1980s he began working on a sprawling novel, “King Comus,” that traces the plights of Jews and blacks deep into 19th-century Europe. He finished the book in 2008, said his son, James, who composes and teaches music in Italy, but it has not found a publisher.

James Demby said his father read excerpts from the book in 2006 when he received anAnisfield-Wolf Book Award for lifetime achievement. The awards recognize books that address racism and diversity.

William Edward Demby Jr. was born on Dec. 25, 1922, in Pittsburgh. His father worked for a gas company and sang in a gospel group. His mother, whose lineage was partly Native American, was a schoolteacher.

After Mr. Demby graduated from high school, his family moved to Clarksburg, W.Va. He briefly attended West Virginia State University before he was drafted into the Army during World War II. He served in North Africa and Italy and wrote for Stars and Stripes, the Army magazine.

Soon after receiving a bachelor’s degree from Fisk University in Nashville in 1947, Mr. Demby returned to Italy, where he met Ms. Drudi in 1950. She died in 1995. During the ’50s he wrote dispatches on the civil rights movement for The Reporter magazine, published in New York.

His second wife and son are his only immediate survivors. He met Ms. Morris, a former lawyer for the N.A.A.C.P., at Fisk, and they married in 2004.

In 1969, Mr. Demby began teaching English at the College of Staten Island of the City University of New York, though he continued to spend part of his time in Italy. He retired in the late 1980s.

He once told The Bloomsbury Review that he recognized his uncertain standing among some critics. “I believed, as I still do, that a black writer has the same kind of mind that writers have had all through time,” he said. “He can imagine any world he wants to imagine.”

__________________________

by Mosaic on June 1, 2013

William Demby: Interview

[William Demby: A Writer’s Life by Steve Kemme

Mosaic #20 October 2007 ]

]

As novelist William Demby left the podium on the stage at the Cleveland Playhouse after addressing a nearly full auditorium, the audience showered him with an enthusiastic ovation. The outpouring of admiration was both gratifying and otherworldly to Demby who has lived mostly outside the margins of the American literary world since his acclaimed first novel, Beetlecreek, appeared in 1950.

“That applause was something I had not experienced,” the 84-year-old Demby said over the telephone earlier this year from his home in Sag Harbor, New York. Demby received a lifetime achievement award at the 71st annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards on September 7, last year in Cleveland. Anisfield-Wolf honors works of fiction and non-fiction that promote racial understanding and cultural diversity. A nifty $10,000 check accompanied the award.

“When they first called me to tell me I had won that award,” Demby said, “I thought it was a mistake.” The only mistake was that no one had bothered to give him a writing award until last year. Why would one of the most singularly talented African-American writers to emerge in the second half of the 20th century have to wait fifty-six years from the publication of his debut novel to receive his first writing award? The vagaries of fame, fortune, and literary institutions don’t completely explain it.

Other factors contributed to his relative obscurity: He has lived in Italy for about half of his adult life; he has published only four novels; and his work defies conventional literary categories. Born in Pittsburgh and raised in Clarksville, West Virginia, Demby attended West Virginia State, where he studied with poet-novelist Margaret Walker until World War II intervened. He joined the U.S. Army in 1942 and was stationed in Italy where he wrote for the military newspaper Stars & Stripes. After the war, he earned a B.A. degree at Fisk University in Nashville. He returned to Italy to study art in Rome and soon decided to make writing his career and Italy his home. He married an Italian writer, Lucia Drudi, and they had a son, James, now a classical music composer and conductor living in Italy.

Demby wrote Beetlecreek at a time when the black protest novel was in vogue. But instead of portraying white society’s injustices to blacks, as Richard Wright, Chester Himes and many other black writers did, Demby created a story about a reclusive outcast white man who is victimized by the nearby black town of Beetlecreek, West Virginia.

The overwhelming desire for conformity and social acceptance among Beetlecreek residents engenders a stifling, stale atmosphere that discourages meaningful action and thought. But few of the town’s residents comprehend the sense of paralysis that grips the town, and even fewer try to break away from it.

After Beetlecreek, Demby became stricken with a creative paralysis of his own and didn’t publish another novel for fifteen years. But he submerged himself in the burgeoning post-war Italian cultural scene and earned a comfortable living translating movie scripts from Italian into English for marketing purposes. He worked for legendary directors like Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, and the master of the spaghetti western, Sergio Leone, as well as the directors of the more commercial action films. He even acted in a 1952 potboiler entitled Il Peccata di Anna (Sin of Anna), playing a murder victim.

“They all came to me to translate scripts because I could do it in lightning speed,” Demby said. “Whenever there was something I didn’t understand in Italian, I would invent something. They laughed about it.”

Seeking ideas for a novel, Demby began reading more than a dozen newspapers a day. He clipped and saved both significant and trivial news stories that interested him. Inspired by Italian collage artist friends, he began creating, in his words, “a literary collage.” Demby merged fictional events with the real events occurring in his life as he wrote his second novel, The Catacombs. He sprinkled the novel with headlines and excerpts from newspaper clippings, providing a historical context as well as comical juxtapositions.

“I got interested in abstract art and the fragmentation of time and place,” he said. “I challenged myself to write a novel like that.”

In The Catacombs, Demby cast himself as the narrator and one of the primary characters–a black American writer searching for his elusive muse as he lives in his adopted country, Italy, and revisits the United States. Demby, his family members, and his friends interact in the novel with the two main fictional characters, a young black woman named Doris and an Italian count.

Published in 1965, The Catacombs is an innovative work, one of the most powerful American novels of that turbulent decade. Although it resonates with the political tensions of the early ’60s, it also dramatizes the timeless struggles of the human spirit. It was so personal in topic and tone that Demby says he couldn’t bear to read the manuscript in its entirety from beginning to end before sending it to the publisher. “It was too frightening,” he said. “You noticed the rhythms and coincidences that were coming from the deepest recesses of your imagination.”

The Catacombs reflects Demby’s decision to avoid the conventional treatment of racial issues. He writes about race in a highly personal, individualistic manner, a fresh perspective shaped by his own aesthetic and his partly European sensibility. As a result, Demby never became a part of the black arts movement of the ’60s and ’70s, which tended to portray racial issues in a narrow, politicized way. “At one point, I had wanted to be like the black writers of the earlier times,” he said. “But if I did that, I told myself, I would be a minstrel man.”

He moved to New York City in the mid-1960s to work for an advertising agency as a copy writer. He says he received important assignments and he found the work exciting. In 1969, Demby became an English professor at the City University of New York’s College of Staten Island, a position he held until he retired in 1987. He says he was never tempted to include his own novels in his classes. “I didn’t think I could do that,” he said. “I did not want to explain what I tried to do.”

His third novel, Love Story Black, was published in 1978. It concerns a Demby-like persona, a middle-aged black male writer in New York City named Bill Edwards who is assigned to research and write a magazine story about Mona Pariss, a once-famous elderly black singer who is living her last years on welfare in a run-down tenement building. Edwards encounters unforeseen obstacles while trying to plumb Pariss’ inscrutable past. With Pariss playing the role of muse much like Doris did in The Catacombs, Edwards’ odyssey leads him to profound discoveries, not only about the elderly woman’s life, but also about disturbing truths concerning race and sex in America.

Love Story Black is a highly satirical novel packed with scenes that are uproariously funny. Demby calls this his favorite among his novels. “It’s the most challenging,” he said. “It involves mysteries I don’t understand, mysteries about youth, sex and aging.”

Demby’s fourth novel, Blueboy, is so obscure and scarce that he’s never even seen it in its published form. He wrote it quickly in the late 1970s to fulfill a requirement for his academic career. He presented the manuscript to his English Department. Before long, he received reported sightings of this novel, which, according to Amazon.com, was published in 1980 by Knopf Paperbacks.

“When I was going to college at Fisk, Blueboy was a name we often gave to a young guy who was very black and kind of doltish,” Demby said. “I imagined this character coming out of a reform school being something like that.” The novel focuses on the friendship this character strikes up with another teenage boy from a very dissimilar background. “It seems to me that near the end of the novel, there was a riot involving old people somewhere in New Jersey,” he said, laughing. He still has no idea how it was published. “I’m glad the novel’s going around,” he said. “I don’t mind. I like mysteries.”

Demby’s first wife died in 1995. He’s now married to Barbara Morris, a friend from his college days he reconnected with after his wife’s death. Demby splits time between his Sag Harbor home and a villa in the mountains outside Florence, Italy, that his first wife inherited from her family. In recent years, he and his son have organized an annual classical music festival at the villa.

Still active at the age of 84, Demby recently finished his fifth novel, King Comus. The novel investigates the historic relationship between blacks and Jews. Demby hasn’t found a publisher for it yet.

Even during the long stretches of his life when he wasn’t writing novels, the creative side of his personality remained fertile and he continued thinking like a writer. “Once you understand that the world is never what you are presented with, that if you turn a corner, you’re going to be presented with an entirely new world,” he said, “that has always and continues to excite me. I like to take chances and imagine other worlds. That is probably the deepest and most influential characteristic of human beings–imagining the life around them and wondering about the magic of the life of others.”

That’s why he’s never agonized about being underappreciated. That’s also why he could smile at the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards last year when a middle-aged woman asked him to autograph her copy of Love Story Black and said, “I just love this novel. Why didn’t I hear of you before?”