Black Germany

History of the

Black Holy Roman Empire

GO HERE TO VIEW IN FULL FORMAT

The fall of Rome

The 476 date for the Fall of Rome is conventionally acceptable because that’s when the Germanic Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor to rule the western part of the Roman Empire. Some say the split into an eastern and western empire governed by separate emperors caused Rome to fall. The eastern half became the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople (modern Istanbul). But there is no doubt that the western Roman Empire fell, and the widespread and long-term social disarray and insecurity following the decline of the Roman Empire and the gradual affiliation of masses of people with military overlords who could protect them constitutes the big picture of medieval society in Europe. And we also know that the White tribes went “Hog-wild”, conquering Roman territories even into North Africa. That left only Byzantium in Anatolia, as the only check against the Albinos marauding throughout Europe. But the problem was that even as the Byzantine Emperors had to deal with the marauding Albinos, they were also constantly at war with the resurgent Persian Sassanian Kings, who wanted to reclaim their former territories in Anatolia and Europe. The Sassanians were very powerful, and had already captured a Roman Emperor.

|

|

|

|

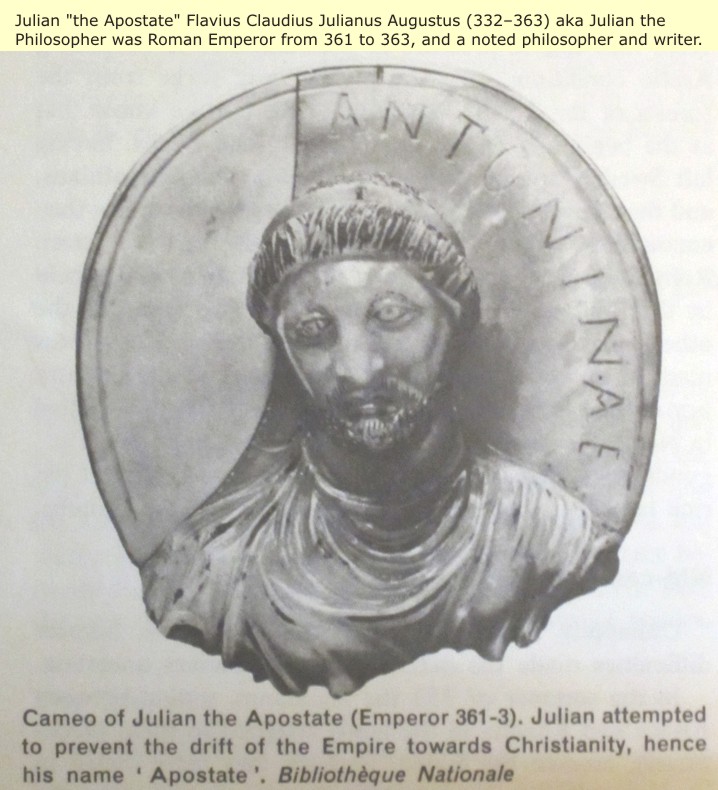

Please note: The above are the only authentic images of Roman Emperors available to the public.

All the others are modern frauds.

The Byzantine Empire

|

The Byzantine Empire was the predominantly Greek-speaking continuation of the Roman Empire during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), which was originally known as Byzantium. Initially it was the eastern half of the Roman Empire (often called the Eastern Roman Empire in this context), it survived the 5th century fragmentation and collapse of the Western Roman Empire, and continued to thrive, existing for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

|

|

|

Byzantium is today distinguished from ancient Rome proper insofar as it was oriented towards Greek culture, characterised by Christianity rather than Roman paganism and was predominantly Greek-speaking rather than Latin-speaking. One of the important early christians was Pope Clement I, later saint Clement. He was the first Apostolic Father of the Church. Few details are known about Clement’s life. According to Tertullian, Clement was consecrated by Saint Peter, and he is known to have been a leading member of the church in Rome in the late 1st century. Early church lists place him as the second or third bishop of Rome after Saint Peter. The Liber Pontificalis presents a list that makes Pope Linus the second in the line of bishops of Rome, with Peter as first; but at the same time it states that Peter ordained two bishops, Linus and Pope Cletus, for the priestly service of the community, devoting himself instead to prayer and preaching, and that it was to Clement that he entrusted the Church as a whole. Appointing him as his successor. Tertullian too makes Clement the immediate successor of Peter. And while in one of his works Jerome gives Clement as “the fourth bishop of Rome after Peter” (not in the sense of fourth successor of Peter, but fourth in a series that included Peter), he adds that “most of the Latins think that Clement was second after the apostle”.

|

Another was John Chrysostom (c. 347–407), Archbishop of Constantinople.

|

Another was Agnes of Rome (c. 291 – c. 304) she is a virgin–martyr, venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, the Anglican Communion, and Lutheranism. She is one of seven women, excluding the Blessed Virgin, commemorated by name in the Canon of the Mass. She is the patron saint of chastity, gardeners, girls, engaged couples, rape victims, and virgins.

|

Whitenized Portrait

|

|

| She is also known as Saint Agnes and Saint Ines. Her memorial, which commemorates her martyrdom, is 21 January in both the Roman Catholic calendar of saints and in the General Roman Calendar of 1962. The 1962 calendar includes a second feast on 28 January, which commemorates her birthday. Agnes is depicted in art with a lamb, as her name resembles the Latin word for “lamb”, agnus. The name “Agnes” is actually derived from the feminine Greek adjective “hagnē” (γνή) meaning “chaste, pure, sacred”. |

According to tradition, Saint Agnes was a member of the Roman nobility born and raised in a Christian family. She suffered martyrdom at the age of twelve or thirteen during the reign of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, on 21 January 304. The Prefect Sempronius wished Agnes to marry his son Procopius, and on Agnes’ refusal he condemned her to death. As Roman law did not permit the execution of virgins, Sempronius had a naked Agnes dragged through the streets to a brothel.

|

Another was Pope Gregory I (540 – 604), better known in English as Gregory the Great, he was pope from 3 September 590 until his death. Gregory is well known for his writings, which were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as pope. Throughout the Middle Ages he was known as “the Father of Christian Worship” because of his exceptional efforts in revising the Roman worship of his day.

|

He is also known as St. Gregory the Dialogist in Eastern Orthodoxy because of his Dialogues. For this reason, English translations of Orthodox texts will sometimes list him as “Gregory Dialogus”. He was the first of the popes to come from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the Latin Fathers. He is considered a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, and some Lutheran churches. Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim. John Calvin admired Gregory and declared in his Institutes that Gregory was the last good pope. He is the patron saint of musicians, singers, students, and teachers.

|

|

If White history was truthful: This Fake would not be Necessary!

|

|

Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire

The first Council of Nicaea (325 A.D.) formalized Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire, and Rome became the center of Christianity. When Rome was sacked by the Albino Germanics in 410 A.D, though the Papacy remained in Rome, Constantinople became predominant. In 800 A.D. Pope Leo III crowned Charles I, king of the Franks (Charlemagne) as Holy Roman Emperor (even though there was already a Roman Emperor in Constantinople). Under the protection of the Frankish Emperors, the Pope was once again able to exert authority.

The divided Church

The East–West Schism of 1054, sometimes known as the Great Schism, formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches, which later became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, respectively. Relations between East and West had long been embittered by political and ecclesiastical differences and theological disputes. There was no single event that marked the breakdown, in the centuries immediately before the schism became definitive, a few short schisms between Constantinople and Rome were followed by reconciliation’s.

Pope Leo IX of Rome and Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerularius heightened the conflict by suppressing Greek and Latin in their respective domains. In 1054, Roman legates traveled to Michael Cerularius to deny him the title Ecumenical Patriarch (first among equals), and to insist that he recognize the Church of Rome’s claim to be the head and mother of the churches, Cerularius refused. The leader of the Latin contingent, Cardinal Humbert, excommunicated Cerularius, while Cerularius in return excommunicated Cardinal Humbert and the other legates. Though efforts were made to reunite the two churches in 1274 (by the Second Council of Lyon) and in 1439 (by the Council of Florence) they ended in failure.

Today, the Eastern Orthodox Church, being continuous, still depicts the original Christians as they really were – as Blacks, (though somewhat Whitenized). The Western Church and its off-shoots: Roman Catholic, Anglican, Anabaptist, Baptist, Congregational, Lutheran, Methodist, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Quaker, Reformed, etc: apparently unafraid of damnation for Heresy, chooses to falsely depict them as Albinos.

Avignon

Avignon was a French city in southeastern France by the left bank of the Rhône river. Often referred to as the “City of Popes” because of the presence of popes and antipopes from 1309 to 1423 during the Catholic schism. In 1309 the city, still part of the Kingdom of Arles, was chosen by Pope Clement V as his residence, and from 1309 until 1377 it was the seat of the Papacy instead of Rome. This caused a schism in the Catholic Church. At the time, the city and the surrounding Comtat Venaissin were ruled by the kings of Sicily of the house of Anjou. The French King Philip the Fair, who had inherited from his father all the rights of Alphonse de Poitiers (the last Count of Toulouse), gave them over to Charles II, King of Naples and Count of Provence (1290). Queen Joanna I of Sicily, as countess of Provence, sold the city to Clement VI for 80,000 florins on 9 June 1348 and though it was later the seat of more than one antipope, Avignon belonged to the Papacy until 1791, when during the French Revolution, it was reincorporated with France.

Seven popes resided there:

Pope Clement V: 1305–1314

Pope John XXII: 1316–1334

Pope Benedict XII: 1334–1342

Pope Clement VI: 1342–1352

Pope Innocent VI: 1352–1362

Pope Urban V: 1362–1370

Pope Gregory XI: 1370–1378

|

|

|

John VIII Palaiologos

John VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus (1392 – 1448), was the penultimate (next to last) reigning Byzantine Emperor, ruling from 1425 to 1448. John VIII was the eldest son of Manuel II Palaiologos and Helena Dragaš, the daughter of the Serbian prince Constantine Dragaš. He was associated as co-emperor with his father before 1416 and became sole emperor in 1425.

|

In June 1422, John VIII Palaiologos supervised the defense of Constantinople during a siege by the Ottoman Turks under Murad II, but had to accept the loss of Thessalonica which his brother Andronikos had given to Venice in 1423. To secure protection against the Ottomans, he visited Pope Eugene IV and consented to the union of the Greek and Roman churches. The Union was ratified at the Council of Florence in 1439 which John attended with 700 followers including Patriarch Joseph II of Constantinople and George Gemistos Plethon, a Neoplatonist philosopher influential among the academics of Italy. The Union failed due to opposition in Constantinople, but through his prudent conduct towards the Ottoman Empire he succeeded in holding possession of the city.

John VIII Palaiologos named his brother Constantine XI, who had served as regent in Constantinople in 1437–1439, as his successor. Despite the machinations of his younger brother Demetrios Palaiologos, his mother Helena was able to secure Constantine XI’s succession in 1448. John VIII died at Constantinople in 1448.

Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Palaiologos (1404 – 1453) was the last reigning Byzantine Emperor from 1449 to his death as member of the Palaiologos dynasty.

The Fall of Constantinople

The siege of the city began in the winter of 1452. Constantine faced the siege defending his city of 60,000 people with an army only numbering 7,000 men. Confronting the Byzantine forces was an Ottoman army numbering many times that, backed by state-of-art siege equipment provided by a very competent Hungarian arms maker named Orban. Before the beginning of the siege, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II made an offer to Constantine XI. In exchange for the surrender of Constantinople, the emperor’s life would be spared and he would continue to rule in Mistra, to which, as preserved by G. Sphrantzes, Constantine replied:

|

“To surrender the city to you is beyond my authority or anyone else’s who lives in it, for all of us, after taking the mutual decision, shall die out of free will without sparing our lives.”

He led the defence of the city and took an active part in the fighting alongside his troops in the land walls. At the same time, he used his diplomatic skills to maintain the necessary unity between the Genovese, Venetian and the Greek troops. He died on 29 May 1453, the day the city fell. His last recorded words were: “The city is fallen and I am still alive”, and then he tore off his imperial ornaments so as to let nothing distinguish him from any other soldier and led his remaining soldiers into a last charge where he was killed.

A false account of the death is recorded by the Ottoman historian Tursun Beg who was an eyewitness at the siege, according to him Constantine was killed by Ottoman azab soldiers while trying to flee with his retinue. After his death in battle during the fall of Constantinople, he became a legendary figure in Greek folklore as the “Marble Emperor” who would awaken and recover the Empire and Constantinople from the Turks. His death marked the end of the Roman Empire, which had continued in the East for 977 years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The Franks

The Frankish Realm or occasionally Frankland, was the territory inhabited and ruled by the Franks from the 3rd to the 10th century. Under the nearly continuous campaigns of Charles Martel, Pepin the Short, and Charlemagne—father, son, grandson—the greatest expansion of the Frankish empire was secured by the early 9th century.

|

|

|

|

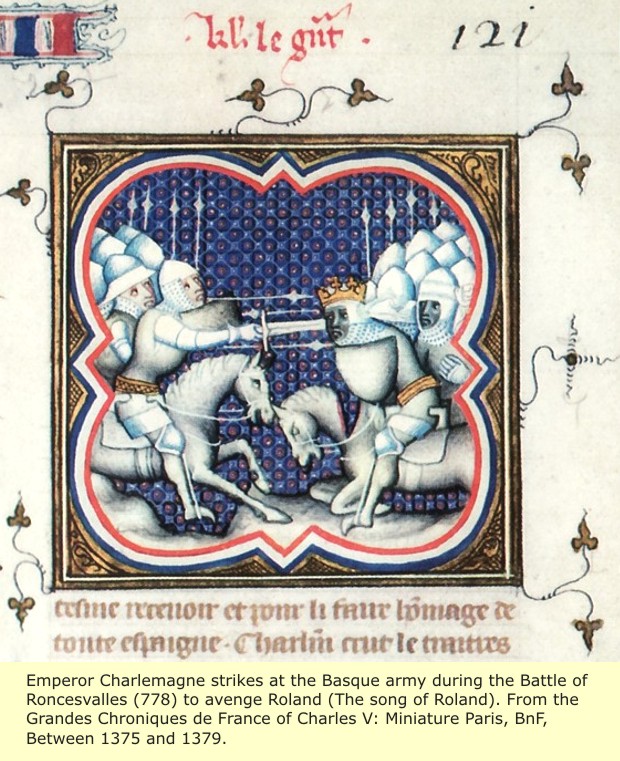

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass (French/English spelling), Roncesvalles in Spanish, (Orreaga in Basque)

The Battle of Roncesvalles and the Song of Roland.Background: Wiki In 774 Husayn of Zaragoza (in the Arabic sources Al Hossain ibn Yahia al Ansari ibn Saad al Obadi), who was Wali (governor) of Zaragoza: now the Spanish province of Aragón. Conspired with the Yemenite aristocracy against the Emir, proclaiming the rule of the Abbasid (Arab) Caliphate in Hispania. In response, the Emir sent general Abd al-Melek bin Umar, who obtained the allegiance of Abu Taur of Huesca and the Wali of Tudela, but who was rejected (defeated?) in Zaragoza. In 777, the Wali of Barcelona, Sulayman al-Arabi (Suleiman bin Ioctan al-Quelbi in the Arabic sources) offered Charlemagne his own allegiance and the allegiance of Husayn (now in Paderborn Germany?). But when in 778 Charlemagne arrived in Zaragoza, Husayn denied any promise. As Charlemagne could not take the city, he withdrew after a month, which then led to the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. In 780 Husayn had Sulayman al-Arabi killed after he returned to Zaragoza. In 781 the Emir Abd ar-Rahman I sent general Tsalaba ben Obaid to re-take Zaragoza for the Caliphate. After a long siege, Husayn agreed to a truce. His son, Said bin Husayn, was given to the Emir as a hostage. According to the historian al-Nuwayri, Husayn was killed soon after his surrender. Encyclopædia Britannica

In La Chanson de Roland the attackers are the Moors, and the rear guard is commanded by Charlemagne’s nephew Roland, who is accompanied by his comrade Oliver and by Archbishop Turpin. Roland, urged by Oliver to sound his horn to recall the main army, is too proud to do so; when the blast is at last blown, it is too late for the returning army to do anything but avenge the main army’s deaths. A similar fate was avoided (811) by Louis I (the Pious), or “le débonnaire,” then king of Aquitaine, who forced the wives and children of the local inhabitants to go through the pass with his army. The Battle of Roncesvalles: History and Legend

|

Carolingian Empire (800–888) is a historiographical term which has been used to refer to the realm of the Franks under the Carolingian dynasty in the Early Middle Ages. This dynasty is seen as the founders of France and Germany, and its beginning date is based on the crowning of Charlemagne, or Charles the Great, and ends with the death of Charles the Fat. Depending on one’s perspective, this Empire can be seen as the later history of the Frankish Realm or the early history of France and of the Holy Roman Empire. The term refers to the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800. Because Charles and his ancestors had been rulers of the Frankish realm earlier (his grandfather Charles Martel had essentially founded the empire during his lifetime), the coronation did not actually constitute a new empire. Most historians prefer to use the term “Frankish Kingdoms” or “Frankish Realm” to refer to the area covering parts of today’s Germany and France from the 5th to the 9th century.

|

The Holy Roman Empire

|

The Holy Roman Emperor: 800 A.D.

It is now 799 A.D, and for the third time in half a century, a Pope is in need of help from the Frankish kings. After being physically attacked by his enemies in the streets of Rome (their stated intention is to blind him and cut out his tongue, to make him incapable of office), Pope Leo III makes his way through the Alps to visit the king of the Franks Charles I at Paderborn. It is not known what is agreed, but Charles I travels to Rome in 800 to support the pope. In a ceremony in St Peter’s, on Christmas Day, Leo is due to anoint Charles I’s son as his heir. But unexpectedly (it is maintained), as Charles I rises from prayer, the pope places a crown on his head and acclaims him emperor.

Charles I (Charlemagne – Charles the great) expresses displeasure but accepts the honour. The displeasure is probably diplomatic, for the legal emperor is undoubtedly the one in Constantinople. Nevertheless this public alliance between the pope and the ruler of a confederation of Black tribes now reflects the reality of political power in the west. And it launches the concept of the new Holy Roman Empire, which will play an important role throughout the Middle Ages.

The Holy Roman Empire only becomes formally established in the next century. But it is implicit in the title adopted by Charlemagne in 800: ‘Charles, most serene Augustus, crowned by God, great and pacific emperor, governing the Roman empire.’

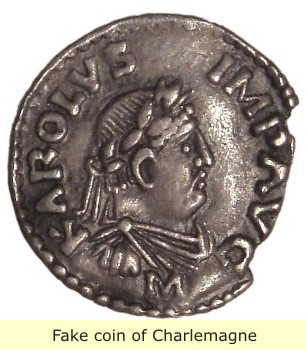

|

|

If White history was truthful: This Fake would not be Necessary! |

|

If White history was truthful: This Fake would not be Necessary! |

|

The Franks and the Byzantine War

In (801-810) Charlemagne and the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I waged war on both land and sea for control of Venetia and the Dalmatian coast (modern-day northern Italy, Slovenia and Croatia). The war progressed well for the Franks, additionally, beginning in 809, Nicephorus was distracted by a new war with the Bulgars. Therefore, the Byzantines began negotiations with the Franks, and peace was agreed upon in which Charlemagne gave up most of the Dalmatian coast (which he had conquered), in exchange for the Byzantine Emperor recognizing him as Emperor of the West. The Istrian Peninsula remained a part of the Frankish Empire.

Then Charlemagne busied himself with driving the Albinos back to the east. Between 802 and 812, Charlemagne fought the Saxons tribes, located to the north. In the beginning of this war, Charlemagne gained his reputation as a ruthless warrior when he massacred over 4,000 Saxons. Still, the warfare with the Saxons continued on. Charlemagne fought the Saxons for thirty years. Finally, he brought Saxony to his kingdom. In (808-810) Charlamagne settled accounts with the Danes, who had given aid and asylum to the Saxon leader Widukind in the Saxon Wars. In (805-806) Charlemagne’s forces subdued the Slavic region of Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic).

Charlemagne was a ruthless warrior, but he had other achievements as well. He provided a good government for his kingdom in which he had outdoor meetings. In these meetings, the mass could vote by shouting out their agreement or disagreement with his offered laws. He charged property taxations, called tithes, so that there would be money to pay for improvements like the five hundred foot bridge up the Rhine River and the cathedral at Ravenna. He raised education too, He brought in teachers from other lands to restore schools. He even started out a school at his palace, Aachen castle. He had monks copy books in the scholarly language of Latin, in order to maintain them.

Charlemagne ruled for about forty seven years. He provided a prosperous and stable country for his people during an era of uncertainty in Europe. He died at the age of seventy two, ruler of a kingdom that included what is now modern France, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, half of Italy, half of Germany, part of Austria, and the Spanish border area.

The interlude

Louis the Pious (778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was the King of Aquitaine from 781. He was also King of the Franks and co-Emperor (as Louis I) with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. As the only surviving adult son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father’s death in 814, a position which he held until his death, save for the period 833–34, during which he was deposed.

During his reign in Aquitaine, Louis was charged with the defence of the Empire’s southwestern frontier. He conquered Barcelona from the Muslims in 801 and asserted Frankish authority over Pamplona and the Basques south of the Pyrenees in 812. As emperor he included his adult sons, Lothair, Pepin, and Louis, in the government and sought to establish a suitable division of the realm among them. The first decade of his reign was characterised by several tragedies and embarrassments, notably the brutal treatment of his nephew Bernard of Italy, for which Louis atoned in a public act of self-debasement. In the 830s his empire was torn by civil war between his sons, only exacerbated by Louis’s attempts to include his son Charles by his second wife in the succession plans. Though his reign ended on a high note, with order largely restored to his empire, it was followed by three years of civil war.

Charles the Bald (823 – 877), was Holy Roman Emperor (875–877, as Charles II) and King of West Francia as Charles II. He was the youngest son of the Emperor Louis the Pious by his second wife Judith. In 875, after the death of the Emperor Louis II (son of his half-brother Lothair): Charles the Bald, supported by Pope John VIII, traveled to Italy, receiving the royal crown at Pavia and the imperial insignia in Rome on 29 December. Louis the German, also a candidate for the succession of Louis II, revenged himself by invading and devastating Charles’ dominions, and Charles had to return hastily to Francia. After the death of Louis the German, Charles in his turn attempted to seize Louis’s kingdom, but was decisively beaten at Andernach on 8 October 876.

|

|

Charles the Bald in old age; picture from a Psalter

|

|

Following the assassination of Berengar of Friuli in 924, the Imperial title had lain vacant for nearly forty years. But in 962 a pope once again needs help against his enemies, and once again he appeals to a strong Frankish ruler. The coronation of Otto I by pope John XII in 962 marks a revival of the concept of a Christian emperor in the west. It is also the beginning of an unbroken line of Holy Roman emperors lasting for more than eight centuries. Otto I does not call himself Roman emperor, but his son Otto II uses the title – as a clear statement of western and papal independence from the other Christian emperor in Constantinople.

| Otto I, the Great (23 November 912 in Wallhausen – 7 May 973 in Memleben), son of Henry I the Fowler and Matilda of Ringelheim, was Duke of Saxony, King of Germany, King of Italy, and “the first of the Germans to be called the emperor of Italy”. |

Edith of England (910 – 26 January 946), also spelt Eadgyth or Ædgyth, was the daughter of Edward the Elder, King of England and Ælfflæd. Her paternal grandparents were Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, and his wife Ealhswith. (The obvious corollary is that Edith came from a long line of Black British royalty).

Otto and his son and grandson (Otto II and Otto III) regard the imperial crown as a mandate to control the Papacy. They dismiss Popes at their will and install replacements more to their liking (sometimes even changing their mind and repeating the process). This power, together with territories covering much of central Europe, gives the Empire and the imperial title great prestige in the late 10th century. But subservience was not the papal intention in reinstating the Holy Roman Empire – A clash is inevitable.

Meanwhile in Iberia

Sancho I, King of Portugal (1154 – 1212). He was the second, but only surviving legitimate son and fourth child of Afonso I of Portugal by his wife, Maud of Savoy. Sancho succeeded his father in 1185. He used the title King of Silves from 1189 until he lost the territory to Almohad control in 1191. In 1170, Sancho was knighted by his father, King Afonso I, and from then on he became his second in command, both administratively and militarily. At this time, the independence of Portugal (declared in 1139) was not firmly established. The kings of León and Castile were trying to re-annex the country and the Roman Catholic Church was late in giving its blessing and approval. Due to this situation Afonso I had to search for allies within the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal made an alliance with the Crown of Aragon and together they fought Castile and León. To secure the agreement, Infante Sancho of Portugal married, Infanta Dulce of Aragon, younger sister of King Alfonso II of Aragon in 1174. Aragon was thus the first Iberian kingdom to recognize the independence of Portugal.

|

With the death of Afonso I in 1185, Sancho I became the second king of Portugal. Coimbra was the centre of his kingdom; Sancho terminated the exhausting and generally pointless wars against his neighbours for control of the Galician borderlands. Instead, he turned all his attentions to the south, towards the Moorish small kingdoms that still thrived. With Crusader help he took Silves in 1191. Silves was an important city of the South, an administrative and commercial town with population estimates around 20,000 people. Sancho ordered the fortification of the city and built a castle which is today an important monument of Portuguese heritage. However, military attention soon had to be turned again to the North, where León and Castile threatened again the Portuguese borders. Silves was again lost to the Moors.

|

Peter I (1068 – 1104) was the King of Aragon and Navarre for a decade from 1094 until his death. He was the son and successor of Sancho V Ramírez by his first wife, Isabella of Urgell. He was named in honour of Saint Peter, because of his father’s special devotion to the Holy See, to which he had made his kingdom a vassal. Peter continued his father’s close alliance with the Church and pursued the Reconquista with even greater success, allying with Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as El Cid, the ruler of Valencia, against the Almoravids. According to the medieval Annales Compostellani Peter was in bellis expertus et audax in principio (“expert in war and daring in initiative”), and one modern historian has remarked that “his grasp of the possibilities inherent in the age seems to have been faultless.”

Papal decline and recovery: 1046-1061 A.D.

The struggle for dominance between emperor and pope comes to a head in two successive reigns, of the emperors Henry III and Henry IV, in the 11th century. The imperial side has a clear win in the first round. In 1046 Henry III deposes three rival popes. Over the next ten years he personally selects four of the next five pontiffs. But after his death, in 1056, these abuses of the system bring a rapid reaction. Pope Nicholas II, elected in 1058, initiates a process of reform which exposes the underlying tension between empire and papacy. In 1059, at a synod in Rome, Nicholas condemns various abuses within the church. These include simony (the selling of clerical posts), the marriage of clergy and, more controversially, corrupt practices in papal elections. Nicholas now restricts the choice of a new pope to a conclave of cardinals, thus ruling out any direct lay influence. Imperial influence is his clear target. In 1061 the assembled bishops of Germany – the emperor’s own faction – declare all the decrees of this pope null and void. Battle is joined. But meanwhile the pope has been enlisting new allies.

|

|

In 1059 Nicholas II takes two political steps of a kind, unusual at this period, which will later be commonplace for the medieval papacy. He grants land, already occupied, to recipients of his own choice; and he involves those recipients in a feudal relationship with the papacy, or the Holy See, as the feudal lord. This time the beneficiaries are the Normans, who are granted territorial rights in southern Italy and Sicily in return for feudal obligations to Rome. The pope, in an overtly political struggle against the German emperor, is playing a strong hand. The issue will be brought to a head within a few years by another pope, Gregory VII.

Gregory VII and investiture: 1075 A.D.

Pope Gregory seizes political control by decreeing, in 1075, that no lay ruler may make ecclesiastical appointments. Powerful bishops and abbots are henceforth to be pope’s men rather than emperor’s men. The issue becomes known as the investiture controversy, being in essence a dispute over who has the right to invest high clerics with the robes and insignia of office. The appointment of bishops and abbots is too valuable a right to be easily relinquished by secular rulers. Great feudal wealth and power is attached to these offices. And high clerics, as the best educated members of the medieval community, are important members of any administration.

In subsequent periods compromises are made on both sides, particularly in the Concordat of Worms, in 1122, where a distinction is made between the spiritual and secular element in clerical appointments. But investiture remains a bone of contention between the papacy and lay rulers – not only in the empire, after the first dramatic flare up between Gregory and Henry IV, but also in France and England.

|

Rome and the struggle for power: 1076-1138 A.D.

The nine-year struggle between pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV provides a vivid glimpse of the political role of the medieval papacy. St Gregory, canonized in the Catholic Reformation, is one of the great defenders of papal power. His career involves incessant power-broking and military struggle. Henry IV, alarmed at the demands being made over investiture, sends a threatening letter to the pope in 1076. The pope responds by excommunicating the emperor. By his public penance at Canossa, Henry has the excommunication lifted. But the truce is short-lived. Henry’s enemies, prompted by the pope’s action, take a hand.

German princes opposed to Henry IV elect and crown, in 1077, a rival king – Rudolf, the duke of Swabia. Rudolf and Henry engage in a civil war, which Henry wins in 1080. By then the pope has recognized Rudolf as the German king and has again excommunicated Henry. This time Henry’s response is more aggressive. He summons a council which deposes the pope and elects in his place the archbishop of Ravenna (as pope Clement III). Henry marches into Italy, enters Rome and is crowned emperor by this pope of his own creation. Meanwhile the real pope, Gregory, is living in a state of siege in his impregnable Roman fortress, the Castel Sant’Angelo.

|

Frederick I Barbarossa was elected King of Germany at Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March, crowned King of Italy in Pavia in 1155, and finally crowned Roman Emperor by Pope Adrian IV, on 18 June 1155. He was then also formally crowned King of Burgundy at Arles on 30 June 1178. The name Barbarossa came from the northern Italian cities he attempted to rule, and means “red beard” in Italian – a mark of both their fear and respect. (In his later years, Frederick apparently took to using Henna to color his graying beard. Henna has been used since the Bronze Age to dye skin (body art), hair, fingernails, leather, silk and wool). Frederick I Barbarossa was elected King of Germany at Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March, crowned King of Italy in Pavia in 1155, and finally crowned Roman Emperor by Pope Adrian IV, on 18 June 1155. He was then also formally crowned King of Burgundy at Arles on 30 June 1178. The name Barbarossa came from the northern Italian cities he attempted to rule, and means “red beard” in Italian – a mark of both their fear and respect. (In his later years, Frederick apparently took to using Henna to color his graying beard. Henna has been used since the Bronze Age to dye skin (body art), hair, fingernails, leather, silk and wool). |

Before his royal election, he was by inheritance Duke of Swabia (1147–1152, as Frederick III). He was the son of Duke Frederick II of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. His mother was Judith, daughter of Henry IX, Duke of Bavaria, from the rival House of Welf, and Frederick therefore descended from Germany’s two leading families, making him an acceptable choice for the Empire’s prince-electors.

Gregory appeals for help to his vassals the Normans, recently invited by the papacy to conquer southern Italy and Sicily. A Norman army reaches Rome in 1084, drives out the Germans and rescues Gregory. But the Norman sack of the city is so violent, and provokes such profound hostility, that Gregory has to flee south with his rescuers. He dies in 1085 in Sicily. Clement III returns to Rome and reigns there with imperial support as pope (or in historical terms as antipope) for most of the next ten years. Urban II, the pope who preaches the first crusade in 1095, is not able to enter the holy city for several years after his election. Unrest prevails in Rome, and uncertainty in the empire, until the Hohenstaufen win the German crown in 1138.

Hohenstaufen: 1138-1254 A.D.

The castle of Staufen, in Swabia, lends its name to the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Frederick, the builder of the castle, is a faithful follower of the emperor Henry IV. In 1079 he marries the emperor’s daughter, Agnes. In 1138, after some years of upheaval and civil war, their son Conrad is elected the German king – as Conrad III. For more than a century, with one minor interruption, members of the Hohenstaufen family inherit the German kingdom – usually together with the status of Holy Roman emperor. The first Hohenstaufen to make a profound impression on the empire is Conrad’s nephew, Frederick I.

In a reign of thirty-eight years Frederick, known also as Frederick Barbarossa, asserts his authority throughout Germany and extends imperial power into Bohemia, Poland and Hungary. But his greatest effort is in Italy, where he tries to recover the empire in the north and to extend it south of the papal states down to Sicily. He meets strong opposition in the north from the Italian communes, who form the Lombard league to resist him. And his attempts in the south are unpopular with the papacy, alarmed at the danger of being surrounded. In the long term Frederick’s most significant act, before his death on crusade in 1190, is to marry his son Henry to Constance, heiress to the Norman kingdom of Sicily.

The marriage of Henry to Constance brings Sicily and southern Italy into the German empire. Henry VI is crowned emperor in Rome in 1191 and king of Sicily in 1194. But he dies shortly afterwards, in 1197, when his son Frederick is just three years old. At first it seems unlikely that the boy can inherit both Sicily and the German kingdom, particularly since the prospect displeases the papacy. From 1198 he is recognized only as king of Sicily. But after a period of confusion, with warring candidates, he is also elected king by the German princes in 1211. With some reluctance the pope accepts the situation. He crowns Frederick II emperor in Rome in 1220.

Subsequent popes have cause to regret this coronation. They excommunicate Frederick II twice, and even proclaim a crusade against him, in a prolonged power struggle which eventually weakens his authority in both Sicily and Germany. In spite of the brilliance of his court in Sicily, and the nonchalant ease with which he achieves his own crusade to Jerusalem, Frederick leaves an inheritance which cannot long survive him. His son, Conrad IV, becomes the last ruler in the Hohenstaufen line. With Conrad’s death, in 1254, there is a vacancy on the German throne which is not filled for another nineteen years.

|

After the Hohenstaufen: 1254-1438 A.D.

The Hohenstaufen period has seen some notably forceful popes (Innocent III, Gregory IX, Innocent IV) and powerful emperors (Frederick I, Frederick II). It is followed, after the death of the last Hohenstaufen ruler in 1254, by a prolonged time of uncertainty in both papacy and empire. The popes abandon Rome in 1309 and spend most of the 14th century in self-imposed exile in Avignon. From 1378 there are two rival popes (a number subsequently rising to three) in the split known as the Great Schism.

Meanwhile, for almost twenty years after the death of Conrad IV in 1254, the German princes fail to elect any effective king or emperor. This period is usually known (with a grandiloquence to match the Great Schism in the papacy) as the Great Interregnum. The interregnum ends with the election of Rudolf I as German king in 1273. The choice subsequently seems of great significance, because he is the first Habsburg on the German throne. But the Habsburg grip on the succession remains far in the future. During the next century the electors choose kings from several families. Not till the coronation of Charles IV in 1346 is there the start of another dynasty – that of the house of Luxembourg.

Before moving on to the Habsburg Dynasty, let us look at an absurdity of Albino European History.

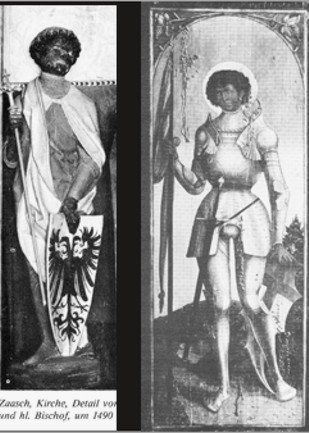

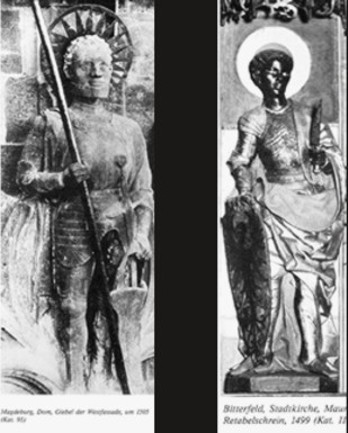

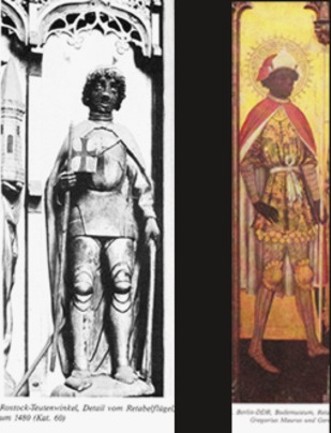

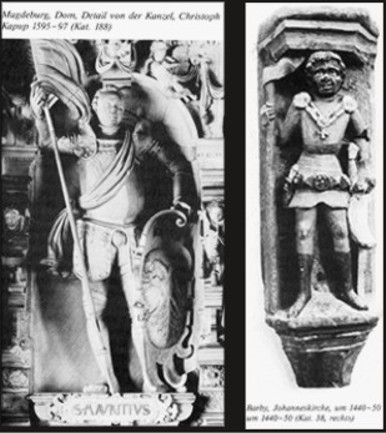

Are all of these Black knights REALLY Saint Maurice???

The Albinos says they are: then again, they declare ALL Black knights to be Saint Maurice. As we all know, there were no Blacks in Medieval Europe – except of course the Slaves and servants. So of course, all of these Black knights couldn’t possibly be REAL people, with their own stories. They must of course, all be that one mythical Black Saint from Egypt, known to us from Roman tales some 1,300 years earlier. But by now, we should all be used to the Albinos degenerate lies.

|

There are hundreds of statues of medieval Black knights, mostly in ancient religious sites, all over Europe, and especially in Germany. Their “Coats of Arms” exist in the hundreds, perhaps thousands. Who then but a fool, would believe that all of those statues represent this one mythical Saint Maurice?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

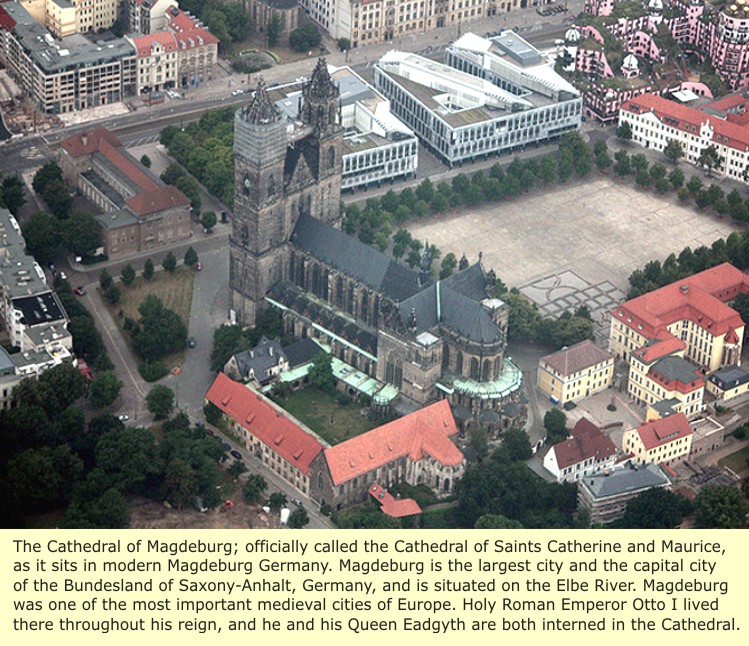

Cathedral of Magdeburg

The “NOW” Protestant Cathedral of Magdeburg, officially called the Cathedral of Saints Catherine and Maurice is the oldest Gothic cathedral in Germany. Today it is the principal church of the Evangelical Church in Central Germany. The first church built in 937 at the location of the current cathedral was an Abbey called Saint Maurice, dedicated to Saint Maurice and financed by Emperor Otto I the Great. Despite being repeatedly looted, the Cathedral of Magdeburg is rich in art, ranging from antiques to modern art.

CATHEDRAL INVENTORY

The cathedral was replaced by an entirely new building after a fire destroyed it in 1207. The architecture and sculptures of this new structure document the transition into Gothic. Archbishop Dietrich dedicated the cathedral in 1363 and the two towers on the west façade were presented by Cardinal Albrecht from Brandenburg in 1520. This marked the end of three-hundred-year-long construction period.

“Despite many attempts, the cathedral’s inventory remained a desire of research,” says researcher Schenkluhn. The Magdeburg Cathedral remains the only former archiepiscopal cathedral of the Middle Ages in Germany without an inventory. A scientifically substantiated inventory is an important requirement for getting the Magdeburg Cathedral on the UNESCO World Heritage list, something which the state is working towards, adds Schenkluhn.

|

The lack of a scientifically valid inventory at Cathedral of Magdeburg allowed racist Albinos to engage in one of their favorite methods of falsifying history, that is to declare all European Blacks as Africans, African Slaves, or the children of African Slaves; without the inconvenience of having to prove what they say.

CLEARLY, AS CAN BE SEEN FROM THE EXAMPLES BELOW, WHAT THE ALBINOS ARE DOING IS DECLARING EVERY STATUE OF A BLACK MAN, OR EVEN SOMEONE WHO LOOKS REMOTELY BLACK, AT MAGDEBURG CATHEDRAL TO BE SAINT MAURICE, RATHER THAN DIVULGING HIS REAL NAME, RANK, AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS.

|

|

Note also that the Dumas family in France gets the same treatment.

Biography of General Alexandre Dumas:

General Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, also known as Alexandre Dumas, (25 March 1762 – 26 February 1806) was the first black general in French history and remains the highest-ranking person of color of all time in a continental European army. He was the first person of color in the French military to become brigadier general, the first to become divisional general, and the first to become general-in-chief of a French army. Dumas shared the status of the highest-ranking black officer in the Western world only with Toussaint Louverture (who in May 1797 became the second black general-in-chief in the French military).

Born in Saint-Domingue, Alexandre Dumas was of mixed race, the son of a white French nobleman and a black slave mother. He was born into slavery because of his mother’s status but was also born into nobility because of his father’s. His father took the boy with him to France in 1776 and had him educated. Slavery was illegal in metropolitan France and thus any slave would be freed de facto by being in the country. He helped him enter the French military.

|

What evidence do the Albinos provide to prove that Dumas was the son of a Slave?

From the Wiki page on Thomas-Alexandre Dumas.

Racial identity

The two extant primary documents that state a racial identity for Marie-Cessette Dumas refer to her as a “négresse” (a black female) as opposed to a “mulâtresse” (a female of mixed race).

Secondary sources on General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, dating back to 1822, almost always describe his mother as a black African (“femme africaine”, “négresse,” “négresse africaine,” “noire,” or “pure black African”

CLEARLY THEN, THE ALBINOS HAVE ESTABLISHED A STANDARD: EVERY BLACK PERSON IN EUROPE WAS AN AFRICAN!

It is clear from these examples and the many, many, more; that the Albinos are attempting to disenfranchise the existence all former Black Europeans, and to declare them Africans. This is to further the Albino lie that there were no indigenous Black Europeans, and that lie is intended to hide the genocide that was perpetrated against Black Europeans at the end of the Medieval period.

Luckily Reynald was always well documented, so the Albinos had no opportunity to lie about this one.

|

But as we have said previously, since the material for almost all of our histories are in Albino hands, our only recourse is to use their material, but use critical analysis and cross referencing to find the truth. As the saying goes, you have a Brain, use it!

Example: The Albinos have identified the Bishop who is taking a tongue lashing from the Black Knight as Albert of Brandenburg, who was a Cardinal and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire (1490 – 1545). From the picture we know that the Knight must be very important and powerful if he can give an Elector and a Cardinal a tongue lashing. So cross referencing to see who Albert was at odds with, we find that it was Ulrich von Hutten (1488 – 1523) who was a German scholar, poet and reformer. He was an outspoken critic of the Roman Catholic Church and a bridge between the humanists and the Lutheran Reformation. He was a leader of the Imperial Knights of the Holy Roman Empire.

Note on the Halos: Neither Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg nor Ulrich von Hutten were Canonized (declared a Saint). Therefore the Halos must have another meaning. Or were placed there later, to justify identifying Ulrich von Hutten as Saint Maurice – put nothing beneath them.

|

Knowing that the Albinos ALWAYS have a fake picture for every important Black person in history, we searched for it. And sure enough, there it was, complete with the laurel on his head.

So now we know two things: those Black knights pictured were indeed REAL people having nothing to do with Saint Maurice – if there ever was such a person. And this particular Knights name is Ulrich von Hutten.

|

The current White occupiers of Germany, try to hide their countries Black Holy Roman Empire past, by modifying remnants of that past. They depict statues and the heads on heraldry of the Holy Roman Empire, with rings in their ears. This is to signify that those people were somehow related to the Moors of North Africa, instead of what they really were: the descendents of the first Human settlers of Europe. This is a favorite trick of all White Europeans, they always identify all Blacks of medieval Europe as Slaves, Servants, or people who came directly from Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

The Race/Religious Wars in Europe

As we shall see later, there were great “Race Wars” now termed “Religious” Wars, in the late medieval period in Europe. These Race wars resulted in the Genocide of Blacks in Europe, and the expulsion of the survivors to the Americas. They came about because ascending European Albinos, whose numbers were constantly increased by new migrants from Central Asia, and finally, the Mongols expulsion of the Turks from Asia, wanted to begin a new era, one completely free of their Black Lords.

Early on, the Albinos apparently realized that one great impediment to their “New Order” was the Catholic Church, with its Black Popes and Black Saints. The saints especially were an integral part of the Catholic Church, their images were prayed to by believers, and they were almost exclusively Black. Obviously, what was needed was a religion without images of Saints.

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was the 16th-century schism within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described “reformers”, who objected to (“protested”) the doctrines, rituals, and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led to the creation of new national Protestant churches. The Reformation was precipitated by earlier events within Europe, such as the Black Death and the Western Schism, which eroded people’s faith in the Catholic Church and the Papacy that governed it.

In general, Northern Europe, with the exception of Ireland and pockets of Britain and the Netherlands, turned Protestant. Southern Europe remained Roman Catholic, while fierce battles which turned into warfare took place in central Europe. The largest of the new churches were the Lutherans (mostly in Germany, the Baltics and Scandinavia) and the Reformed churches (mostly in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Scotland). There were many smaller bodies as well. The most common dating of the Protestant Reformation begins in 1517, when Luther published The Ninety-Five Theses, and concludes in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia that ended years of European religious wars.

England

The separation of the Church of England (or Anglican Church) from Rome under Henry VIII, beginning in 1529 and completed in 1537, brought England alongside this broad Reformation movement; however, religious changes in the English national church proceeded more conservatively than elsewhere in Europe. Reformers in the Church of England alternated, for centuries, between sympathies for ancient Catholic tradition and more Reformed principles, gradually developing into a tradition considered a middle way (via media) between the Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions.

The Albino victory in Europe did leave some loose ends for modern Albinos: all of those formerly Catholic churches with their statues and paintings of Black Saints and Madonna’s, which the lay people of the past would not allow to be destroyed. The solution was very simple: SAY THAT THE MADONNA’S ARE A NOVELITY, AND THE SAINTS ARE ALL SAINT MAURICE!

As with all silly lies, the falsity is immediately apparent. The mythical Saint Maurice was a Roman soldier, the (the Egyptian/Ethiopian) leader of the legendary Roman Theban Legion in the 3rd century, who would obviously wear a Roman uniform. See Saint Martin of Tours here, he was also a Roman soldier of the same period, note that he is depicted wearing a Roman uniform of his period: (Also note that he is Black – that will of course be changed later).

|

Compare now with the Holy Roman Empire soldiers above, falsely identified as St. Maurice, who are depicted wearing the uniform of medieval Knights of the Holy Roman Empire.

Sometime after the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church also fell under the control of Europe’s Albinos. For the western Catholic church, new statues and paintings of the Madonna and the Saints were created – they now depicted Albinos. The Albinos developed cottage industries devoted to creating new statues and paintings which looked like ancient artifacts. However for the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Black Madonna’s and Saints were mostly kept, though now with mostly Albino features.

|

Clich here to see Black Madonna’s and Black saints

Click here to see how fakes are created for manuscripts

Even the current Pope, Benedict XVI, who is of German extraction, does the same thing. The Black Freising King on the Pope’s “Coat of Arms” shows the Freising King (probably Otto I) with a ring in his ear. You will note that none of the people depicted here, have a ring in their ears.

Even more ridiculous, is the explanation for the Freising King on the Popes “Coat of Arms”.

Example of explanation found at Wiki

The crowned blackamoor

A legend tells of Abraham of Freising traveling one night through the Poljanska dolina valley with his black servant. While walking through a dark thicket they came across a huge bear. Abraham stopped, terrified; the quick-thinking servant aimed an arrow from his bow and shot the bear dead. The bishop embraced him and proclaimed: “You have saved my life, servant. I shall reward you, so that future generations may know what a hero you were.” He showed his gratitude by depicting his servant’s head (caput aethiopis) in the bishopric’s and the town’s coat of arms. The “Freising blackamoor” was demonstrably first utilized in 1284 by Bishop Emicho of Wittelsbach. An inscription on the outer part of a 14th century seal reads SIGILLUM CIVITATIS LOK – seal of the town of Škofja Loka.

|

Interestingly, after we posted that in about August of 2010, it has since been cleansed from the web. Funny how when the Albinos are confronted for their lies, their lies disappear. After all, when authentic artifacts and true history is brought to bear, who but a fool would believe their nonsense?

Except of course, Blacks who are paid to believe their nonsense. Mainstream Black academics are quite happy to believe the Albinos nonsense, their incomes depend on it. So while they are happy to show that Blacks actually existed in history, they will take it no further. To do so would mean an end to their place of favor among the Albinos, and an end to their comfortable incomes.

|

Henry Louis Gates

|

|

|

His video: http://www.thebostonchannel.com/r-video/26136385/detail.html Note: the video IS worth watching, and the books are probably worth buying, but only for the wonderful artifacts shown. |

|

|

|

>via: http://realhistoryww.com/world_history/ancient/Misc/Crests/History_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire_2.htm

Thank God for the truth suggested reading blacks who died for Jesus by Harmon Crawford