The Real—and

Really Creepy—

Lesson of That

‘Atlantic’

Slave Story

Yes, the mother was cruel, but

the important point is

Lola’s kindness in the face of

that cruelty, and how it was used

against her to sustain her oppression.

“My Family’s Slave” has taken a life of its own since

publication last week. The story has prompted more

Americans to describe the existence of modern forms of

slavery, share personal experiences, and critique the

author Alex Tizon’s depiction of his family’s slave,

Eudocia Tomas Pulido, whom they called Lola. For the

most part, people have been critical of Tizon’s family

while also appreciating his efforts to liberate Lola.

facade of friendship between Lola and Tizon’s mother

as they grew old together, juxtaposed with Tizon’s

decision to not discuss Lola around his mother. This

evolution of their relationship might seem heartwarming

on the surface, but in fact it shows how the humanity

of the oppressed can be used to sustain their own

oppression.

Tizon’s grandfather bought Lola in the late 1940s in The

Philippines, where he lived at the time, when she was

only 12. He gave her to Tizon’s mother. In 1964, Tizon’s

family moved to America and brought Lola with them.

Lola’s life consisted of serving Tizon’s family. She cooked,

cleaned, took care of the children, and never had a life

beyond the needs of this family.She was never paid. She made no friends and had no romantic relationships. For decades, she received constant verbal and physical abuse. For years, the Tizons did not even give her a bed to sleep on, so she slept on a couch or a pile of dirty laundry. Yet despite his family’s relentless torture of Lola, she expressed an unconditional amount of love towards his family.

Tizon goes on to tell of the time his father left the family, when the author was 15, and how Lola became the shoulder for his mother to cry on as she struggled to cope with the burden of raising her family “on her own,” (ignoring both Lola’s contribution and her dependence on Lola). The added stress made her even more demanding, but her lack of a spouse meant that she also needed an adult she could talk to.

“As Mom snapped at her over small things, Lola attended to her even more—cooking Mom’s favorite meals, cleaning her bedroom with extra care,” said Tizon. “One night I heard Mom weeping and ran into the living room to find her slumped in Lola’s arms. Lola was talking softly to her, the way she used to with my siblings and me when we were young.”

Yet Lola’s kindness was not reciprocated. Tizon’s mother still let her teeth rot and refused to take her to the dentist. When her children defended Lola, tried to assist her with household chores, or pleaded with their mother to take her to the dentist, she ridiculed her children and made Lola’s life even worse. She’d blame Lola for turning her kids against her and would become verbally abusive.

As the years went by, Tizon’s mother remarried and slowly but surely, she became nicer to Lola. She bought her a nice set of dentures, and took her on vacations to the beach with her new husband. From the outside looking in, I’m sure that it would be easy to view Lola and Tizon’s mother as two elderly friends.

However, Lola always remained an afterthought to his mother. At one point, Tizon found her diary, and he saw that Lola was nothing more than a persistent footnote in their history. She was always there, but hardly discussed. Tizon would eventually stop discussing Lola when he was around his mother because it would anger her and because reminding himself of his mother’s abuse of Lola made it harder to forge a relationship with her.

When his mother died, Lola was not far away. Tizon’s mother never apologized or asked for forgiveness for how she treated Lola. After her death, Lola moved in with Tizon’s family, and he spent the rest of his life trying to give Lola the life of freedom that she deserved.

As an African American who is the descendent of slaves, I cannot help but look at this story and imagine many similar interactions between blacks and whites in the 1800s and before.

Additionally, what struck me the most as I was reading about Lola’s infinite patience with the slights and cruelties she endured with such equanimity was how her grace in the face of adversity could be used to sustain her oppression.

Tizon remained committed to breaking his family’s connection to slavery, but he also wanted to build a strong loving relationship with his mother. He wanted to find a way to love her, and as he got older that meant ignoring the plight of Lola, which further sustained her oppression.

This combination of love of family and the survival techniques of the oppressed can incline oppressors and their descendants to ignore and distort the horrors of the society in which they perpetuate.

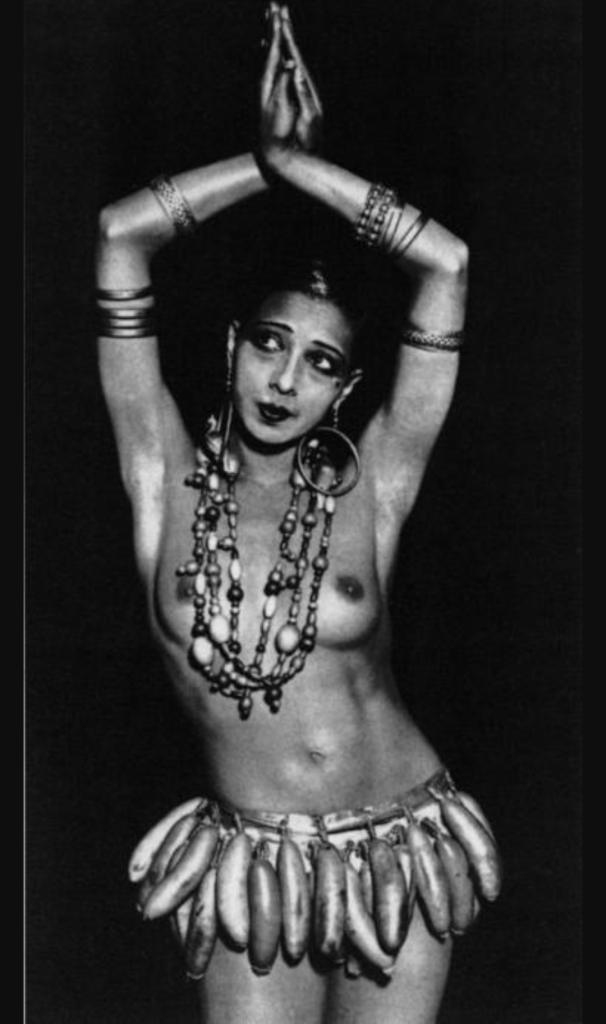

American slave owners and their offspring have used this template to downplay the severity of American slavery, and reinforce the false narrative of blacks being better off enslaved. The fact that slaves did not kill slave owners in their sleep, and showed compassion to them when they were vulnerable, enabled a pseudo-absolving of the sin of slavery among white Americans. The kindness of the enslaved perpetuated this lunacy for generations.

During Reconstruction, former slave owners in the South were shocked that the freed blacks refused to work on their plantations. These slave owners thought that they had treated their slaves well. The kindness of the enslaved had convinced these slave owners that the enslaved had actually enjoyed their dehumanizing status.

Today, segments of America still honor the Confederacy. Their “Heritage Not Hate” argument echoes Tizon’s quest to find a way to love his mother. Whether in the former Confederacy as a whole, or within the Tizon family, if you remove racism, terrorism, and slavery from the equation, these Southern sympathizers have now found an ancestor they feel comfortable loving. Yet in doing so, they only perpetuate racial oppression.

And when confronted by terror, African Americans still choose to invoke our shared humanity as our defense mechanism. Following the massacre at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina many of the victims expressed compassion and forgiveness instead of revenge for Dylann Roof. They expressed a civil, compassionate response to racist terror. This week following the murder of Richard Collins III by a white supremacist we exuded the same grace.

Additionally, following the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and others, African Americans rallied around the Black Lives Matter movement. This movement was not about demonizing white Americans or any American, but instead was intended to raise the cultural awareness of the lives and struggles of black Americans. The controversy surrounding this movement stemmed from merely bringing up the topic of black lives. This is similar to how Tizon opted to not discuss Lola around his mother. Lola’s existence, or what they had turned her existence into, could not be spoken of, for it would make them hate themselves. BLM elicits a similar form of dread and animus.

As a child Tizon was punished for defending Lola. And as an adult he opted to ignore Lola’s existence when around his mother to avoid a fight and to see the humanity of his mother instead of the tyrant in her. Throughout all of this Lola worked to embrace the humanity of her oppressors because this was her only way to survive in this dehumanizing environment. Eventually, Tizon decided to break the chain of slavery, give Lola the best shot at freedom that he could create, and reciprocate the humanity that she had shown his family.

As a people, African Americans have survived by embracing the humanity of their oppressors and waiting for a reciprocity that rarely arrives.