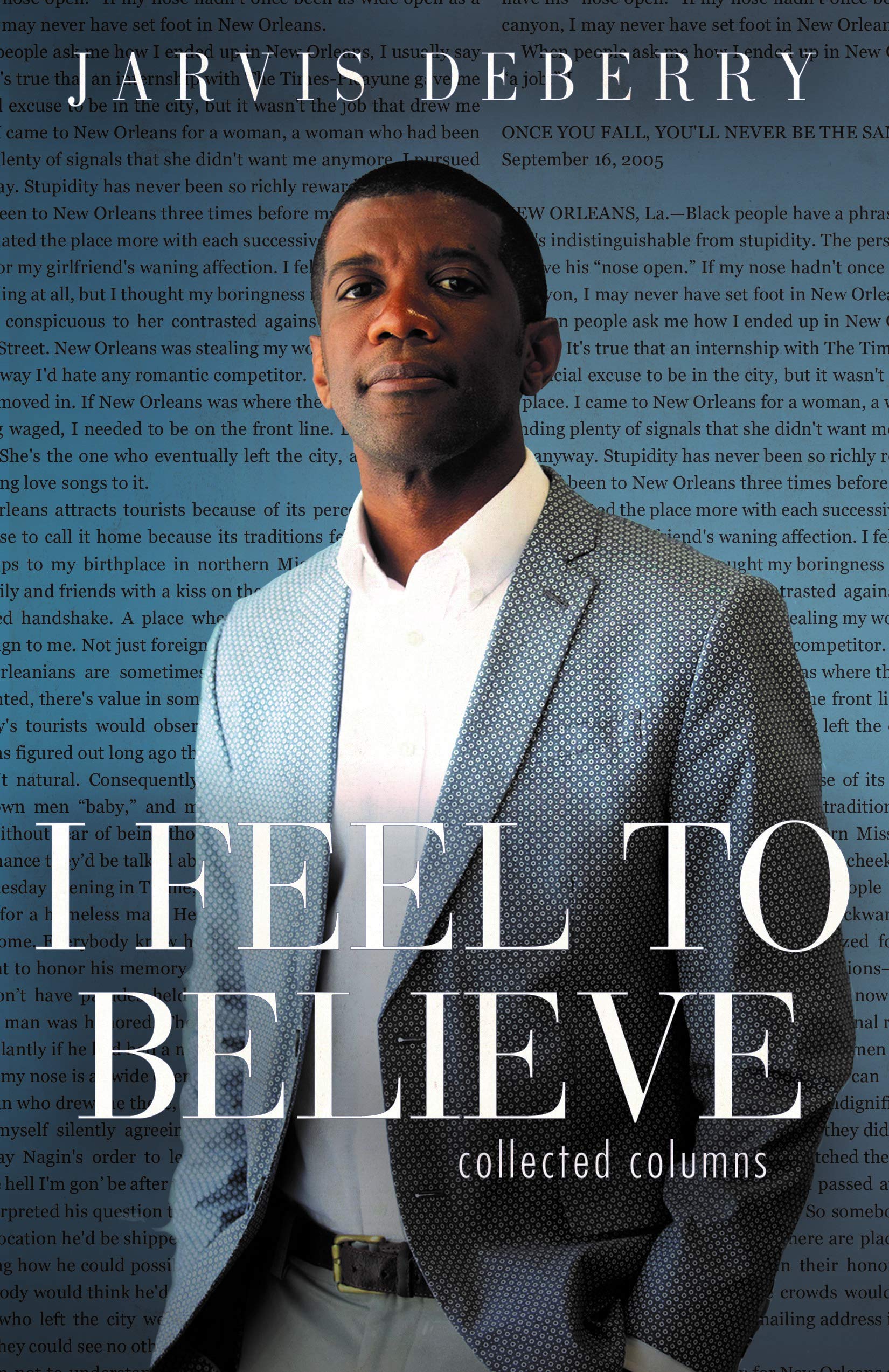

photo by Alex Lear

What does it mean to be a man?

1.

In the human reproductive process, the role of the man is to transmit his seed to the woman, wherein the seed fertilizes the egg, and eventually the egg transforms into a fetus, which grows in the woman’s womb and over a period of time becomes an infant, that in turn is ejected, and in some cases, physically removed from the female, and becomes an individual.

The functions of males and females in the reproductive cycle is essential to all mammals. In that sense, there is no major argument about what it means for a male to be a man.

However, sociologically the definition of manhood is a major question. In the U.S., defining manhood is riven by a racial divide and a gender divide, as well as massively influenced by economic, or class, considerations.

National political independence was formalized in 1776, but women did not receive the right to vote until 1920. Moreover, despite the tumult of the Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 9, 1865), massive rights for Black people beyond titular citizenship was not formalized until the 1964 Civil Rights Act (July 2) and the 1965 Voting Rights Act (August 6). Racial restrictions were effectively the law of the land for the majority of this country’s existence–a country that has been dominated, and largely ruled, by White men.

From a legal perspective, gender issues have been sublimated to racial and economic concerns, hence, even though men are not the majority of citizens, men are the majority of authority figures in this society and control the bulk of the economy.

2.

To put it bluntly, although throughout our history there may have been questions or concerns among specific groupings, nevertheless, there is generally no legal controversy about what it means to be a man if the male is White. Why is that?

When we speak of manhood in general terms, rather than solely as a biological reality, inevitably the meaning is a specific social construct: White manhood. In America, even when we mean those who are other than White, even when people like me refer to ourselves, we can not escape the environmental mainstream reality: White manhood ipso facto defines (and restricts) our conception and practice of manhood.

Two competing and often conflicting issues confront us. 1. What does it mean to be a man–and that’s an issue we generally do not deal with in any depth beyond the biological. 2. What does it mean to be a Black man, which is loaded with all kinds of sociological baggage?

Inherent in the mythology of White manhood is the concept of conqueror and/or ultimate authority figure.

Inherent in the mythology of Black manhood is the concept of lesser than the ultimate authority figure, i.e. lesser than “the man”.

Neither mythology is universally true. However, both are widely accepted.

From the alleged “founding fathers”, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and a host, although lesser celebrated, grouping of other White men, on to the contemporary President of the United States and the heads of major corporations, the image of the White man is of an authority figure, who is often either a military man, a major political official, or a “captain of industry”, i.e. an economic figure. Hence, to be a man means to be in charge of society, whether that society be an individual family unit, a business concern, the nation as a whole, or any other formation in-between.

An American man dominates, physically or economically, or ideally in both categories. This obviously creates a major problem for Black males when it comes to defining us as men. How can we dominate physically or economically and at the same time function within the bounds of a society that demeans/confines us? At best in this society we are allowed to function as entertainers and/or athletes, the only two areas wherein society at large is comfortable recognizing Black males as dominant?

Consider why Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is celebrated while Malcolm X, i.e. El Hajj Malik Shabazz, is vilified. King non-violently wielded the teachings of the bible, Malcolm militantly was popularly photographed with a rifle in his hands.

Consider why Muhammad Ali was questioned and widely rejected when he was a dominant force in the boxing ring and only after his boxing prime could he be safely and globally celebrated as an “all American” entertainment figure or a social statesman who lovingly embraced all people.

Go deeper, why from Bojangles, on down to a plethora of Black sidekicks in the movies, on to Bill Crosby (the ultimate sidekick/lovable father figure), and so many others, why are these men celebrated and at the same time portrayed as non-threatening to society at large?

Whenever a Black man acts like a White man and dominates as a physical force, that man is often demeaned, if not outright condemned. This is specifically the case when the Black man (a la O.J. Simpson or Bill Cosby) is revealed to be a sexual predator, which is precisely what White men too often were, especially the celebrated Thomas Jefferson!

3.

Thomas Jefferson is generally acclaimed as a major author of the Declaration of Independence while at the same time being a slave master who had sexual relations with at least one of the young women whom he lorded over.

The Jefferson example leads us directly into the American contradiction: how can a Black man successfully be a man if being a man means being a conqueror, i.e. a dominant political and/or economic force in society, and also means being a sexual being who preys on women?

What is the basis for the near universal (in western mythology) acclaim and admiration for Casanova or for Casanova-like behavior vis-a-vis women?

This social conundrum gets both more complex and more confusing when we interrogate gender relations and the status of women in modern America.

Taking this analysis beyond easy to grasp social arithmetic into the realm of complex gender calculus, we begin to see that once we move pass procreation into the territory of pleasure, then we find (and for some of us, we discover) that pleasure is not limited by or confined to binary gender relations.

It is one easy move to deal with the definition of manhood when we only consider males and the conditions affecting males as defining what it means to be a man, but when we consider relations between genders, i.e. when we consider what women say and what male relations to women means, then defining who is a man is no longer an easy, pleasurable move.

Moreover, what can be pleasure for one is torture, or at best an accepted/required duty, for the passive sexual partner, whose status is not necessarily binary nor age limited.

On a 1787 voyage to France, Sarah Hemings was taken to Paris, where she joined Thomas Jefferson. Hemings was Jefferson’s teenage concubine–while it is certain she was his sexual object, whether she was his lover, i.e., whether they were involved in a mutual romantic relationship, is doubtful. Ms. Hemings did not have any legal agency nor any ability to deny or consent to the relationship with Jefferson.

The Thomas Jefferson case is just one particular in a much, much larger social reality of men legally and extra-legally, sexually dominating women.

4.

Yes, there is much more to manhood than sex. In the context of the American norm, to be a man also means assuming responsibility for the economic and social well-being of the nuclear family. In that regard, for a plurality of Black households, particularly for those households at the borders of middle-class status, and especially for those who are working class and lower, the raw fact of life in those households, paradoxically, is that the woman functions as the man, especially the single Black woman who has a child or children to rear, to educate, and to support. Or to use a seemingly oxymoronic, albeit not inaccurate, catch-phrase: in a plurality, if not the majority, of Black homes, the woman is “the man”!

To be more precise, in the reality of most Black people, “the man” is often a woman. This is why patriarchy is so challenged by Black women. Their social status as the de facto “man of the household” implicitly challenges the notion that the man is in charge when the reality is that the woman is the sole provider for the household. This is especially true when the man is absent, and undoubtedly so when the man is incarcerated.

Moreover, for many males, of whatever color, within the context of the nuclear family, being a patriarch is the only definition of manhood that they understand, and too often, to the detriment of gender relations, dominating patriarchy is the only definition of manhood that they embrace.

However, because Black women so often must assume all but the procreative aspects of the generally accepted social definitions of manhood, in terms of day-to-day existence, the very definition of manhood is actually un-gendered, or at least de-coupled from patriarchy, which is why, except for procreation, in many, many cases, and under a wide variety of settings, the woman is factually “the man”. Seen?

Who says that women can’t be the man in social terms? Certainly that is not the case in many Black households. If a woman can function as a man, does that mean that males in general are socially castrated, and, as a result, are rendered social eunuchs?

Many men will say that they like strong women, but do they really? Within the context of social relations, does any man want to be in a relationship with a woman who functions as a man does? Or put in less combative terms, can any man embrace patriarchy and, at the same time, embrace a woman who functions as a man?

When we are looking at and socially evaluating the image of a man, what is it we are really contemplating? In a biological sense, “maleness” has a limited and very specific definition. However, in the larger social sense, “manhood” is a definition that reality proves is not limited only to males.

What does it mean to be a man, and, beyond biology, can a woman be a man? What we really need is a new, another, definition of manhood.

5.

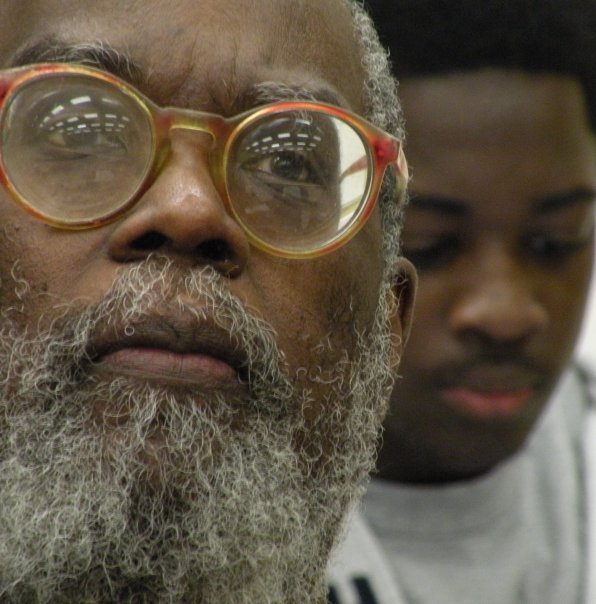

There are so many questions to be explored. Can a homosexual be a man, e.g. was James Baldwin a man? While it is popular to say that only a man can teach a boy to become a man, is that actually true or is it simply a patriarchal truism? So many millions of Black men were reared by Black women in female-headed households.

However, there are biological specifics that can not be ignored. Yes, when compared to women, men may be the sole providers of semen, nevertheless, men can not breast-feed a baby. Biology can not be ignored, but at the same time, biology does not solely, or fully–not to mention exclusively–define both individual and social concepts of manhood.

What prevents any adult, be they male or female, from fulfilling the general social definitions of what it means to be a man? Indeed, realistically, how do we define what it means to be “the” man of the household? Biology does not negate social equality. We work with gender-restrictive definitions of manhood and womanhood at our peril, especially when we confront pleasure and/or social responsibility as a major aspect of our definitions.

Rigidity is a hallmark of the patriarchal definition of manhood, however, social reality is actually much less restrictive. Our behavior as social creatures exists on a spectrum. While the work of artists does not challenge or change the human spectrum, artists do extend far beyond a single restricted spot on the spectrum of social activity.

6.

Great art is far more than simply a reflection of our human condition. In the American social context, great art is actually also a projection of social beliefs, realities, romances and possibilities.

We are more than our thoughts. This is especially so because our thoughts have been shaped, if not totally defined, by our environment in combination with the ways in which we were reared.

To move beyond how we were born and reared requires extraordinary insight and action. Particularly for Black people existing within a racially and gender defined environment, art has offered one of the most effective alternatives broadly available.

While it is true that famous entertainers and athletes are considered dominant individuals, the greater truth is that the influential power of an artist’s career can greatly exceed the limited time period allocated to the impact of entertainers, and especially exceeds the small window of athletic dominance. Well beyond the limits of a particular lifetime, artists are often celebrated decades and even centuries after their physical demise.

The artist is an individual who acts on deep insights and whose work reflects their thoughts. Artists do what they do in a manner that is graceful, i.e. is shaped or influenced by a beautiful way of being. By actually producing important objects and/or events, artists not only express themselves, artists also deeply influence their audience. Indeed, artists explicitly define the essence of being a human being. At the most primal level, making art makes us human.

The very process of making art is an important social barometer that identifies and signifies the zeitgeist of Black life.

In the racially restrictive American society, over the years, Black artists have been representative of exceeding the normative conditions of Black people. Especially by their existence and work, artists go beyond mainstream conceptions of the status and the social reality of who Black people are individually and collectively. Artists always exist outside of mainstream concerns, and in a limited sense, also exist outside of mainstream controls.

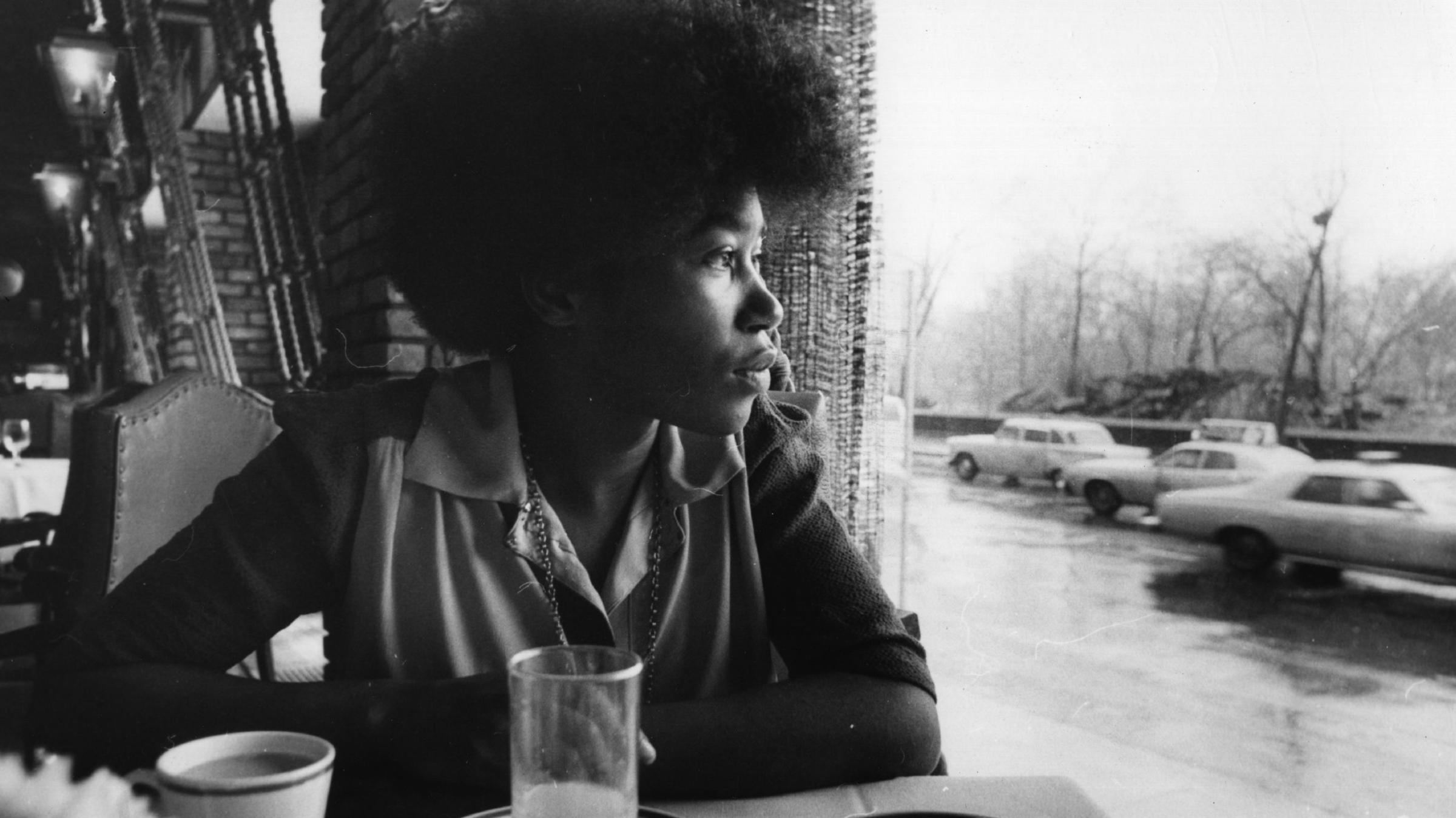

Like Nina Simone, I believe that the work and worth of Black artists is specifically to reflect their times. At their best, Black artists also challenge the thinking prevalent during their times, especially the ontological question of what does it mean to be Black, male, and artist.

In a paradoxical way, a challenge to social conceptions not only gives the lie to the mainstream conception, that challenge also demonstrates both what is lacking and/or diminutive/demeaning about how the mainstream views Blackness. More importantly, the challenge also points to the potentials, possibilities and very real power of Blackness to not only survive but indeed to thrive in an environment of anti-Blackness.

7.

Being a man means much more than what one sees when one sees a male. Inside the home and in society as a whole, what does a man do? What does an active, self-determining man do? In a visually obsessive society, what does a man look like? Are manhood and maleness synonymous?

Especially presented from the perspective and work of Black artists, there are many questions to ponder as we think on the meaning and reality of being a man. Moreover, this obsession with “manhood”, with being a man, is an Achilles heel of our humanity. What we really should focus on is what does it mean to be an adult, especially given the fact that as we age, the majority of adults are female.

Particularly in the Black community, women far outlive men. This is not an ennobling statistic, not one we should take pride in, rather, the lasting longevity of women and the limited longevity of men is a social reality that reflects the restrictive mainstream social conditions confronting Black males.

Being a Black man is no simple occupation. Manhood requires both thought and action. As the African liberation leader Amilcar Cabral advised, we should “Mask no difficulties. Tell no lies. Claim no easy victories.”

Being a man is difficult, requires telling the truth, and is no easy path to trod to grasp the victory of what it means to fully be a man.

Cabral’s self description is simple but not simplistic. Saying it–is easy, being it–is arduous. Cabral proclaimed: “I am a simple African man, doing my duty in my own country in the context of our time.”

Cabral thereby articulates the basic definition of being “a simple African man”–one does whatever is one’s duty, in one’s own country, and in the context of one’s own time.

Be ye male or female, when we become adults, our essence is to accept and fulfill our responsibilities. Whatever the ever changing realities, we must confront and surmount, doing so is the task: the ultimate definition of achieving successful manhood and womanhood.

To be is to do. Within whatever constraints and within the possibilities of whatever time and space, being a man or woman is doing the work of living with and relating to others.