“White Cotton, Black Pickers” / Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In Memory of Cedric Robinson (1940–2016)

It is a commonplace to say that slavery “dehumanized” enslaved people, but to do so is misleading, harmful, and worth resisting.

I hasten to add that there are, of course, plenty of right-minded reasons for adopting the notion of “dehumanization.” It is hard to square the idea of millions of people being bought and sold, of systematic sexual violation, natal alienation, forced labor, and starvation with any sort of “humane” behavior: these are the sorts of things that should never be done to human beings. By terming these actions “inhuman” and suggesting that they either relied upon or accomplished the “dehumanization” of enslaved people, however, we are participating in a sort of ideological exchange that is no less baleful for being so familiar. We are separating a normative and aspirational notion of humanity from the sorts of exploitation and violence that history suggests may well be definitive of human beings: we are separating ourselves from our own histories of perpetration. To say so is not to suggest that there is no difference between the past and the present; it is merely that we should not overwrite the complex determinations of history with simple-minded notions of moral progress.

More important, though, is the ideological work accomplished by holding on to a normative notion of “humanity”—one that can be held separate from the “inhuman” actions of so many humans. Historians sometimes argue that some aspects of slavery were so violent, so obscene, so “inhuman” that, in order to live with themselves, the perpetrators had to somehow “dehumanize” their victims. While that “somehow” remains a problem—for it is never really specified what combination of unconscious, cultural, and social factors make a “somehow”—I want to question the assumption that slaveholders had to first “dehumanize” their slaves before they could swing a baby by the feet into a post to silence its cries, or jam the broken handle of a hoe down the throat of a field hand, or refer to their property as “darkies” or “hands” or “wool.”

The apparent right-mindedness of such arguments notwithstanding, this language of “dehumanization” is misleading because slavery depended upon the human capacities of enslaved people. It depended upon their reproduction. It depended upon their labor. And it depended upon their sentience. Enslaved people could be taught: their intelligence made them valuable. They could be manipulated: their desires could make them pliable. They could be terrorized: their fears could make them controllable. And they could be tortured: beaten, starved, raped, humiliated, degraded. It is these last that are conventionally understood to be the most “inhuman” of slaveholders’ actions and those that most “dehumanized” enslaved people. And yet these actions epitomize the failure of this set of terms to capture what was at stake in slaveholding violence: the extent to which slaveholders depended upon violated slaves to bear witness, to provide satisfaction, to provide a living, human register of slaveholders’ power.

What if we use the history of slavery

as a standpoint from which to rethink

our notion of justice today?

More than misleading, however, the notion that enslavement “dehumanized” enslaved people is harmful; it indelibly and categorically alters those with whom it supposedly sympathizes. Dehumanization suggests an alienation of enslaved people from their humanity. Who is the judge of when a person has suffered so much or been objectified so fundamentally that the person’s humanity has been lost? How does the person regain that humanity? Can it even be regained? And who decides when it has been regained? The explicitly paternalist character of these questions suggests that a belief in the “dehumanization” of enslaved people is locked in an inextricable embrace with the very history of racial abjection it ostensibly confronts. All this while implicitly asserting the unimpeachable rectitude and “humanity” of latter-day observers.

It could be argued that my interpretation of the word “dehumanized” is grammatically fundamentalist and intellectually obtuse, that the point of saying that slavery “dehumanized” enslaved people is to draw attention to the immoral actions of slaveholders—their inhumanity—rather than to make a claim about the abjection of enslaved people. I would respond by citing Philip Morgan’s Slave Counterpoint, a prizewinning history of slavery in eighteenth-century North America. In the introduction, Morgan emphasizes that African American slaves “strove . . . to preserve their humanity.”

Even as many historians explicitly and insistently vindicate the notion that enslaved people were human beings, they also implicitly and unwittingly suggest that the case for enslaved humanity is in need of being proven again and again. By framing their “discovery” of the enduring humanity of enslaved people as a defining feature of their work, by casting their work as proof of black humanity—as if this were a question that should even be posed—historians ironically render black humanity intellectually probationary. Efforts to separate “human” from “inhuman” and “dehumanized” thus create an unanticipated set of intellectual and ethical overflows.

Elsewhere in the same introduction, Morgan writes:

Wherever and whenever masters, whether implicitly or explicitly, recognized the independent will and volition of their slaves, they acknowledged the humanity of their bondpeople. Extracting this admission was, in fact, a form of slave resistance, because slaves thereby opposed the dehumanization inherent in their status.

I want to emphasize that I am not quoting these sentences because they are exceptionally imperceptive. I quote them instead because they are emblematic: by counterpoising an emphasis on “independent will and volition” against the possibility of “dehumanization,” they crystallize a set of intellectual impulses and ethical premises that undergirds much of the scholarship on slavery. They frame their account of humanity as an aspect of the problem of freedom, and freedom of a very particular sort: the freedom to make choices and take intended actions—in other words, the bourgeois freedoms of classical liberalism. In so doing, they point to the peculiar complications that result from positioning the history of slavery at the juncture of the terms “human” and “rights.”

Several problems flow from the notion that every history of slavery is peopled by liberal subjects striving to be emancipated into the political condition of the twenty-first-century Western bourgeoisie. From a historiographic perspective, we could say that this perspective alienates enslaved people from the historical parameters and cultural determinants of their own actions. It takes their actions—from singing a spiritual to breaking a tool to fomenting a revolution to having a good idea about how to run a better sluiceway—and collapses them down to a single anachronistic and essentially liberal moral: enslaved people’s “agency” proved their humanity.

For the purposes of this essay, I am less interested in the historiographic implications of this line of reasoning than I am in its ethical dimensions. The tension between the specific actions and idioms of enslaved life and the broadly comparative categories of “independent will and volition,” “agency,” and “humanity” seem analogically—and, indeed, historically and ethically—related to the tension that Karl Marx noted between the historical and material inequalities of nineteenth-century society and the abstract equality of rights-based human emancipation, of which he was critical. In his essay “On the Jewish Question,” Marx wrote that the political citizen was “an imaginary member of an imaginary universality.” For Marx the material salients of human existence—“distinctions of birth, social rank, education, occupation”—continued to guide and determine the course of history, even as the inauguration of a new sort of history, the history of political equality, was announced to the world. In a passage that captures both the terrific promises and bounded limits of a rights-based notion of human emancipation, Marx wrote:

Political emancipation is, of course, a big step forward. True, it is not the final form of human emancipation, but it is the final form of human emancipation within the hitherto existing world order. It goes without saying that we are speaking here of [something greater than that] real, practical emancipation.

It is through Marx’s appreciation for and critique of the notion of citizenship—and, by extension, of the rights-based notion of the human being at the heart of the historiography of slavery—that I want to turn more directly to the question of human rights.

A good deal of recent scholarship has emphasized the importance of both vernacular and institutional antislavery to the intellectual history of human rights. Samuel Moyn’s recent and influential account of the history of human rights, however, departs from this timeline to argue for a much later set of historical benchmarks. It was not until well into the twentieth century, Moyn argues, that the idea of “a new world” emerged, “in which the dignity of each individual will enjoy secure international protection.” While many other scholars are critical of the way that Moyn’s timeline sets the history of slavery and antislavery to the side of the history of human rights, I think Moyn is not without reason. The version of human rights that dominates contemporary super-sovereign rights claims, I would suggest, is not significantly inflected by the history of slavery, although it would be better if it were.

Our current notion of universal human rights has its origin in a particular historical experience: that of Europe in the twentieth century. Human-rights thinking has emphasized the universal rights of democratic self-determination, freedom of conscience and expression, protection from political violence and, above all, the anathematization of genocide. Paraphrasing Marx, I think it is fair to say that the emergence of a global movement in support of human rights is the summary accomplishment of “the hitherto existing world order.” It is not, however—nor in my view should it be—“the final form of human emancipation” or of what a just world should look like. In Moyn’s view, in fact, human-rights thinking has provided the intellectual architecture for a sort of liberal neo-imperialism, the justifying terms of continuing European and American intervention in the affairs of former colonies.

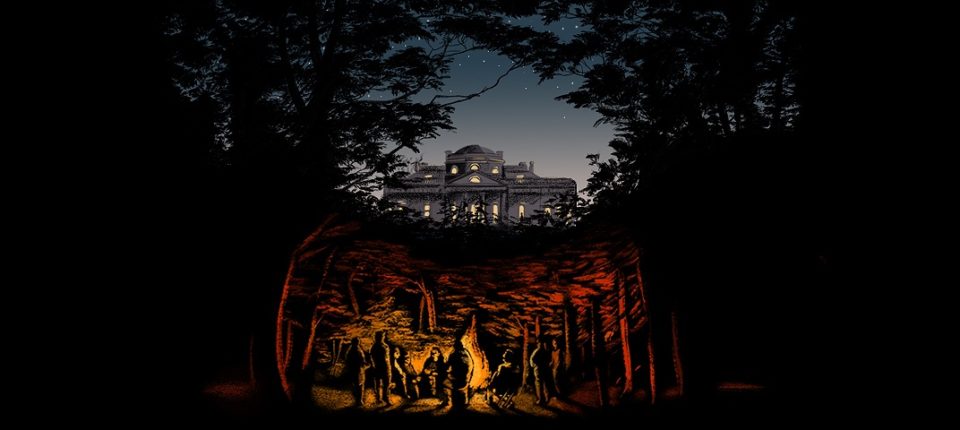

There is a quite different genealogy for discussions of human freedom—this one rooted in the experience of slavery rather than the question of the humanity of slaves. The Movement for Black Lives proposal, “A Vision for Black Lives,” insists on a relationship between the history of slavery and contemporary struggles for social justice. At the heart of the proposal is a call for “reparations for the historic and continuing harms of colonialism and slavery.” Indeed, the ambient as well as the activist discussion of justice in the United States today is inseparable from the history of slavery.

The idea that enslavement “dehumanized”

enslaved people suggests that their

humanity needs to be proven again

and again.

With this in mind, we might return to the question of “human emancipation”—this time with the purpose of essaying a notion of justice that is rooted in the history of slavery and goes beyond liberal notions of human rights. Through this route, we can arrive at a history of the global political economy that is attentive to what, following Cedric Robinson, I term racial capitalism.

In Black Marxism (1983), Robinson argues that the historical developments of capitalism and racism were inseparable. Engaging with black nationalism and orthodox Marxism, he argues that the path toward the just and the good cannot be found in the “authoritarian” pronouncements of uninflected Marxism, with its single route to revolution, nor in the historical “simplications” of black nationalism, which threatens to replicate white-dominated institutions but with black people in charge. Instead the path to justice is located in the black radical tradition: in the democratic practices and revolutionary thought of black people living under conditions of racial capitalism.

Black Marxism begins with a history of slavery in medieval Europe, in part to demonstrate the historically contingent character of the relationship between slavery and blackness. It then turns to the early modern period and the European enslavement of Africans. In the era of the Atlantic slave trade, new notions of difference—absolute, racial notions of difference—were used to define, describe, and justify the political economy of slavery.

For Robinson, W. E. B. Du Bois was the preeminent historian of the ways that racism had defined the history of capitalism and interrupted the universalist pretensions of Marxist orthodoxy. In a 1920 essay entitled “The Souls of White Folk,” Du Bois suggests that both economic exploitation and domination justified by imagined difference have histories “as old as mankind.” But their combination in European imperialism—the “discovery of personal whiteness” by those who claimed title to the world and the concomitant designation of the world’s dark peoples as “beasts of burden”—is recent, a product of the slave trade. Gone in Du Bois are the orthodox markers that serve to keep the history of slavery separate from the history of capitalism. In their place Du Bois proposes a new milestone, the emergence of a sort of capitalism that relies upon the elaboration, reproduction, and exploitation of notions of racial difference: a global capitalism concomitant with the invention of what Robinson termed “the universal Negro.” In short: racial capitalism.

In Black Reconstruction in America, published fifteen years later, Du Bois roots his account of racial capitalism in the history of slavery in the United States. “The giant forces of water and of steam were harnessed to do the world’s work, and the black workers of America bent at the bottom of a growing pyramid of commerce and industry; and they not only could not be spared, if this new economic organization was to expand, but rather they became the cause of new political demands and alignments, of new dreams of power and visions of empire,” he writes in the book’s first pages.

Black labor became the foundation stone not only of the Southern social structure, but of Northern manufacture and commerce, of the English factory system, of European commerce, of buying and selling on a world-wide scale; new cities were built on the results of black labor, and a new labor problem, involving all white labor, arose in both Europe and America.

In a few sentences, Du Bois scuttles the orthodox separation of slavery and capitalism. He names his history of American slavery “The Black Worker”—a subject, at once, of capital and of white supremacy. This, Robinson writes, was “the beginning of the transformation of the historiography of American Civilization—the naming of things.”

Rather than following Adam Smith or Karl Marx, each of whom viewed slavery as a residual form in the world of emergent capitalism, Du Bois treats the plantations of Mississippi, the counting houses of Manhattan, and the mills of Manchester as differentiated but concomitant components of a single system. Many scholars have expressed a fear that terming both what happened in Mississippi and what happened in Manchester “capitalism” will make it impossible to see the trees for the forest—“obscuring,” in the words of James Oakes, “fundamental differences between economies based on enslaved [and] free labor.” But there is no obvious reason that should be the case. Arguing that the history of (racial) capitalism began with the slave trade rather than the factory system does not necessarily pose any greater threat to historical and analytical precision than arguing that both Harriet Tubman and John C. Calhoun were human beings.

Indeed, Du Bois draws attention to the very differences that Oakes worries will be elided. He simply sees the production of these differences as an aspect of the history he is trying to understand, rather than as an inevitable answer to which any historical account must aspire. The history of white working-class struggle, for example, cannot be understood separate from the privileges of whiteness, to which the white working classes of Britain and the United States laid claim in their demands for equal political rights. And it was the ever-expanding frontier of imperialism and racial capitalism that pacified the white working class with the threat of replacement and promise of a share of the spoils. The history of racial capitalism, it must be emphasized, is a history of wages as well as whips, of factories as well as plantations, of whiteness as well as blackness, of “freedom” as well as slavery.

Critically, there is nothing static or simple about this formulation. Du Bois does not argue that all whites benefit from capitalism while all blacks do not. But nor does he argue that blacks and whites are “workers” in the same way. He suggests instead a subtle and dynamic relationship between capitalist exploitation and white supremacy. Likewise, Du Bois insists on a coeval and dialectical relationship between metropole and colony: even as the economic spaces of the global South were reconfigured in relation to northern capital, metropolitan class relationships were reconfigured around ideas of freedom and entitlement that emerged from imperialism and slavery.

Du Bois’s famous invocation of the “wages of whiteness” can best be understood in the context of a global economy that entwined Mississippi, Manhattan, and Manchester together in a white-supremacist system of differential rights and entitlements. Under the dominion of cotton, metropolitan wage workers came to understand themselves as white and to measure their entitlement in terms of slavery and empire: as natural and just when they shared in the spoils; as insupportable and impious when they did not.

Far from obscuring the differences between the social relations of production in the various regions of the world, Black Reconstructionprovides an account of their historical interconnection, their racial predication, and their functional differentiation. “The abolition of American slavery,” Du Bois writes, “started the transportation of capital from white to black countries where slavery prevailed . . . and precipitated the modern economic degradation of the white farmer, while it put into the hands of the owners of the machine such a monopoly of raw material that their dominion of white labor was more and more complete.” The end of slavery in the United States, according to Du Bois, marked not the liberation of the independent forces of capitalism and freedom from their archaic interconnection with slavery, but the generalization on a global scale of the racial and imperial vision of the “empire of cotton.” The history of racial capitalism is a history of the interconnected process by which economic, geographic, and racial differences were seeded, took root, and finally grew up to such an extent that they obscured efforts to search out their common origin: a history, at once, of integrative connection and divisive particularization.

Perhaps the fullest expression of Du Bois’s account of global racial capitalism is in his 1946 book The World and Africa. There he describes the process by which “slavery and the slave trade became transformed into anti-slavery and colonialism, and all with the same determination and demand to increase profit an investment.” Although this meant that terms of European stewardship were transformed, even at times inverted, the racial pattern of extraction and exploitation nonetheless continued unabated.

It all became a characteristic drama of capitalist exploitation, where the right hand knew nothing of what the left hand did, yet rhymed its grip with uncanny timeliness; where the investor neither knew, nor inquired, nor greatly cared about the sources of his profits; where the enslaved or dead or half-paid worker never saw nor dreamed of the value of his work (now owned by others); where neither the society darling nor the great artist saw the blood on the piano keys; where the clubman, boasting of great game hunting, heard above the click of his smooth, lovely, resilient billiard balls no echo of the wild shrieks of pain from kindly, half-human beasts as fifty to seventy-five thousand each year were slaughtered in cold, cruel, lingering horror of living death; sending their teeth to adorn civilization on the bowed heads and chained feet of thirty thousand black slaves, leaving behind more than a hundred thousand corpses in broken, flaming homes.

As much as anything, this is an account of the spatial aspect of racial capitalism. It emphasizes both the intimate, violent proximities and the material and cognitive distances of region, race, and scale (global and imperial, intimate and proximate). Du Bois’s account is particularly interested in the material culture of racial capital, of how the suffering of dead elephants and enslaved Africans was reassembled elsewhere as sensory pleasures for the parlors and pool halls of imperial London. It is an environmental history of the resource-extracting, race-differentiating, world-wasting race to the end of time. Uncannily, the most ambitious and perceptive examples of the “new history of capitalism” turn out to have been written over seventy years ago.

Implicit in the insight of racial capitalism is the claim that there is something fundamental and racial (or, more precisely, racist) that is elided by the conventional understanding of capitalism’s origins. With this parallax in mind, the burden of proof rests on the notion’s advocates to show what is gained by thinking outward from the history of slavery to an overarching idea of racial capitalism. A history of capitalism framed by categories derived from analysis of the mills of Manchester might have seemed to make sense in the era of the miners’ strike in Great Britain or of George Meany and the AFL-CIO in the United States (although the murder of Vincent Chin, among countless other examples, suggests otherwise). The history of American slavery, however, seems a more apt starting point for the analysis of a world characterized by the global division of labor, the resurgence of slavery as mode of production, the emergence of personal services (and pornography) as leading sectors of the economy, and the effulgence of nativism and white nationalism as fundamental features of white working-class ideology. History has moved on, and in so doing it has reshuffled its own past.

Much of the scholarship on slavery

has relied upon a pat liberal notion

of human rights as its moral paradigm.

Indeed, the history of capitalism makes no sense separate from the history of the slave trade and its aftermath. There was no such thing as capitalism without slavery: the history of Manchester never happened without the history of Mississippi. In Capitalism and Slavery (1944), Eric Williams gives a detailed account of the supersession of British colonial interests by manufacturing ones and the replacement of cotton with sugar as the foundation of capitalist development. Williams argues that Great Britain freed its slaves, but did not free itself from slavery. British capitalists simply outsourced the production of the raw material upon which they principally depended to the United States. During the antebellum period, 85 percent of the cotton produced in the United States was exported to Great Britain. During the same period 85 percent of the cotton manufactured in Great Britain was imported in raw form from the United States. Raw cotton was thus the largest single export of the United States and the largest single import of Great Britain.

Trying to abstract the social relations of production that characterized British (or American) cotton mills from the rest of the economy that gave them life—and then identifying this as the paradigmatic example of “capitalism”—quite simply does not make sense. “Would Great Britain have industrialized without slavery, though perhaps at a different pace or in a different way?” James Oakes has recently written. What is being proposed is an adventitious, ahistorical definition of capitalism—a thing which might have happened even though it actually did not—that serves no purpose except to preserve, at whatever cost, the analytical precedence of Europe over Africa, the factory over the field, and the white working class over black slaves. Capitalism counterfactually emancipated from slavery. That is not social science; it is science fiction.

Rather than asking over and over what Marx said about slavery, we should follow Robinson in asking what slavery says about Marx. We should use the history of slavery as the source rather than the subject of knowledge. Let us begin with the most basic distinction in political economy: the distinction between capital and labor. Enslaved people were both. Their double economic aspect could not be separated and graphed on the axes of a Cartesian grid; their interests could not be balanced against one another or subordinated to one another in an effort to secure social order. They were both.

And so, too, were their children: racial capitalism swung on a reproductive hinge. The entire “pyramid” of the Atlantic economy of the nineteenth century (the economy that has been treated as the paradigmatic example of capitalism) was founded upon the capacity of enslaved women’s bodies: upon their ability to reproduce capital. As Deborah Gray White points out, sexual violation, reproductive invigilation, and natal alienation were elementary aspects of slavery, and thus of racial capitalism. The alternative, of course, was the slave trade. As the slaveholder J. D. B. DeBow stated in his 1858 argument for reopening the Atlantic slave trade to the United States (which had been outlawed in 1808), it was either that or “await with folded arms the coming of population and of labor which will be the result of natural increase.” A commercial mode of social reproduction would make black women disposable.

The political economy of the nineteenth century was founded on these basic facts. Every year the cotton merchants of Great Britain made tremendous advances to the cotton planters of the South. The planters used the credit to purchase seeds and tools and slaves and the food to feed them, and they planned to use those slaves to plant and pick and pack and ship the cotton that would cover the money that had been advanced to them, and then some. As pro-slavery political economist Thomas Kettel wrote in 1860:

The agriculturalists, who create the real wealth of the country, are not in daily receipt of money. Their produce is ready but once a year, whereas they buy supplies [on credit] year round. . . . The whole banking system of the country is based primarily on this bill movement against produce.

In case the cotton proved too scant or poor to cover the amount that had been advanced against its eventual sale, or in case the cotton market dipped in the time between when an advance was made and the time the crop came in, cotton merchants required some sort of security from the planters to whom they loaned money. That security was the value of the enslaved. Therefore, given that enslaved people were the collateral upon which the entire system depended, it seems absurd to persist in asking whether the political economy of slavery was or was not “capitalist.” Enslaved people were the capital. Their value in 1860 was equal to all of the capital invested in American railroads, manufacturing, and agricultural land combined.

It is important to add that the land tells a different part of the story, one that resounds with Du Bois’s emphasis on empire alongside enslavement as the primary categories of capitalist accumulation. The land that enslaved people planted in cotton and which their owners posted as collateral was Native American land: it had been expropriated from the Creek, the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Seminole. Indeed, if one traces the legal history of private property in the United States back, trying to find a legal foundation for determining why (legally rather than morally speaking) we own what we think we own, at the bottom lies the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the case of Johnson v. McIntosh(1823). At stake in the case was the question of whether white settlers could purchase land directly from native inhabitants, and the answer of the Supreme Court was “no.” Native American lands, the court ruled, must be passed through the public domain of the United States before being converted into the private property of white inhabitants. In other words, the foundation of the law of property in the United States combines, at once, the imperial assertion of U.S. sovereignty and the identification of that project with continental racial governance.

The version of human rights that

dominates contemporary discourse

is not significantly inflected by

the history of slavery, although

it would be better if it were.

The racial capitalism of the nineteenth century was founded upon the racialization and instrumentalization, the commodification and securitization, the expropriation and forcible transportation, the sexual violation and reproductive alienation of Africans and Native Americans. It is here we must begin to reimagine the categories against which we stretch the past into historical meaning, to follow the lead of those who self-consciously work in the tradition of Du Bois and Robinson: scholars such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Adam Green, Cheryl Harris, Peter Hudson, Robin D. G. Kelley, George Lipsitz, Lisa Lowe, Gary Okihiro, Nell Irvin Painter, David Roediger, Alexander Saxton, and Stephanie Smallwood. And no longer should the “capitalism-slavery debate” proceed without a full and forthright acknowledgement of and engagement with the pioneering work and enduring insights of W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, Eric Williams, Walter Rodney, Angela Davis, and Cedric Robinson.

Let me return to the relationship between the history of slavery and contemporary notions of justice. Tragically, the history of slavery is increasingly being written without enslaved people. By this, I mean that a field formerly defined by the dissident, bottom-up methodology of African American Studies and social history is increasingly dominated by work that does not ask questions about the experiences, ideas, or history of the enslaved (even while it teaches us many new things about slaveholders and their business partners). Let me be clear: it is not only nonsensical but also unethical to continue asking whether slavery was capitalist without asking what that meant to enslaved people—to investigate what Du Bois termed “the philosophy of life and action which slavery bred in the souls of black folk.”

From the history of the enslaved, we might make our way back toward the question of rights. I began by suggesting that much of the scholarship on slavery has unwittingly relied upon a pat liberal notion of human rights as its moral paradigm—despite the clear contradiction between the universalization of a bourgeois liberal actor and the legal and experiential realities of American slavery. The culturally dominant notion of human rights is not only unreflective of the history of slavery; it is unresponsive to the specific patterns of injustice that follow from the history of slavery. In its place, I suggest the possibility of using the history of slavery as a standpoint from which to rethink our notion of justice. What is left is to delineate the usefulness of this history to an account of justice.

There are six principal virtues of an account of justice rooted in the history of slavery and racial capitalism:

First, it mounts its critique of modern injustice from the standpoint of Africa and what has come to be called “the global South,” rather than from Europe and “the global North.”

Second, it focuses on the extraction and distribution of resources between classes and areas of the world: on the relationship of African American history to Native American history, for example, or on the relationship of either or both of those to the history of the white workers (and merchants and bankers) in the financial and manufacturing centers of the United States and Europe. So doing, it proposes the generalization of an account of historical wrong based in the experiences of the dark and dispossessed rather than in those of the metropolitan bourgeoisie.

Third, it emphasizes the ways in which present distributions of privilege and abjection are related to past patterns. It opens a pathway along which historically deep notions of restorative justice and reparations, rather than a synchronic focus on “rights,” might be seen as the only adequate form of redress.

Fourth, it insists upon a notion of justice attentive to questions of gender and sexuality, on the ways that reproductive invigilation and natal alienation—the subordination of the social reproduction of one group of people to the purposes of another—were core features of the human wrongs of slavery.

Fifth, it asserts a direct relationship between—and indeed, the functional sameness of—what are conventionally separated as the politics of “race” and “class.” It correlates both the entitlement and vulnerability of the white working class with the subjection of the “dark proletariat,” and connects the insistent racialization of the global working class to the operations of capital.

Sixth, it suggests the possibility of relating a critique of the instrumentalization of human beings through slavery to the instrumentalization of nature in capitalist forms of extraction. Over and against many recent efforts which assert that a forthright treatment of global environmental history requires the elevation of the categories of the “human” and the “Anthropocene” over and against other historical categories—principally those of race, class, gender, and colonialism—it insists upon the intimate and dialectical relationship between domination and dominion.

In The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America (1896), an extended description of the various heartless and cynical prevarications through which the United States evaded the suppression of the Atlantic slave trade, Du Bois made an argument about the character of historical time. There were, in his view, moments that were propitious for change, moments when it was possible—with courageous and concerted action—to remake the world in its own better image. The cost, for Du Bois, of missing those moments could only be reckoned in the blood of the subsequent generations who paid the price for their forebears’ failures. Perhaps we should heed his warning.