photo by RAJAH BOSE

I‘m sitting across from Rachel Dolezal, and she looks… white. Not a little white, not racially ambiguous. Dolezal looks really, really white. She looks like a white woman with a mild suntan, in box braids—like perhaps she’d just gotten back from a Caribbean vacation and decided to keep the hairstyle for a few days “for fun.”

She is also smaller than I expected, tiny even—even in her wedge heels and jeans. I’m six feet tall and fat. I wonder for a moment what this conversation might look like to bystanders if things were to get heated—a giant black woman interrogating a tiny white woman. Everything about Dolezal is smaller than expected—the tiny house she rents, the limited and very used furniture. Her 1-year-old son toddles in front of cartoons playing on a small television. The only thing of real size in the house seems to be a painting of her adopted brother, and now adopted son, Izaiah, from when he was a young child. The painting looms over Dolezal on the living-room wall as she begins to talk. I try to get my bearings and listen to what she’s trying to say, but for the first few moments, my mind keeps repeating: “How in the hell did I get here?”

I did not want to think about, talk about, or write about Rachel Dolezal ever again. While many people have been highly entertained by the story of a woman who passed herself off for almost a decade as a black woman, even rising to the head of the Spokane chapter of the NAACP, before being “outed” during a TV interview by KXLY reporter Jeff Humphrey as white, as later confirmed by her white parents, I found little amusement in her continued spotlight. When the story first broke in June 2015, I was approached by more editors in a week than I had heard from in two months. They were all looking for “fresh takes” on the Dolezal scandal from the very people whose identity had now been put up for debate—black women. I wrote two pieces on Dolezal for two different websites, mostly focused not on her, but on the lack of understanding of black women’s identity that was causing the conversation about Dolezal to become more and more painful for so many black women.

After a few weeks of media obsession, I—and most of the other black women I knew—was completely done with Rachel Dolezal.

Or, at least I hoped to be.

Right after turning in a draft of my book on race at the end of February, I went to a theater to do an onstage interview on race and intersectionality (a mode of thinking that intersects identities and systems of social oppression and domination). But before going onstage, my phone buzzed with a “news” alert. Rachel Dolezal had changed her name. I quickly glanced at the article and saw that Dolezal had changed her name to Nkechi Amare Diallo. My jaw dropped in disbelief. Nkechi is my sister’s name—my visibly black sister born and raised in Nigeria. Dolezal claimed that the name change was to make it easier for her to get a job, because the scandal had made it so that nobody in the Eastern Washington town of Spokane (pop. 210,000) would look at an application with the name Rachel Dolezal on it.

I’m going to pause here so we can recognize the absurdity of this claim: You change your name from Rachel Dolezal to Nkechi Amare Diallo because everyone in your lily-white town (Spokane is more than 80 percent white) now knows you as the Rachel Dolezal who was pretending to be black, so you change your name to NKECHI AMARE DIALLO because somehow they won’t know who you are then. Maybe they’ll just confuse you with all the other Nkechi Amare Diallos in Spokane and not think when a white woman shows up for the interview: “Oh yeah, it’s that white woman who pretended to be black and then changed her name to NKECHI AMARE DIALLO.” Also, even if there were 50 Nkechi Amare Diallos in Spokane—trust me, as someone named Ijeoma Oluo who grew up in the white Seattle suburb of Lynnwood—you’d have a much better chance of getting a job interview if you changed your name to Sarah.

By the time I finished my interview on that rainy February day, my cell phone indicated that I had a voice mail. It was The Stranger, asking if I would spend the day with Rachel Dolezal.

For two years, I, like many other black women who talk or write about racial justice, have tried to avoid Rachel Dolezal—but she follows us wherever we go. So if I couldn’t get away from her, I was going to at least try to figure out why. I surprised myself by agreeing to the interview.

I began to get nervous as the interview day approached. By the time I boarded a plane to Spokane, which is a one-hour flight from Seattle and is near the border with Idaho, a state that’s almost 90 percent white, I was half sure that this interview was my worst career decision to date. Initially, I had hoped that my research on Dolezal would reassure me that there was a way to find real value in this conversation, that there would be a way to actually turn this circus into a productive discussion on race in America.

But then I read her book.

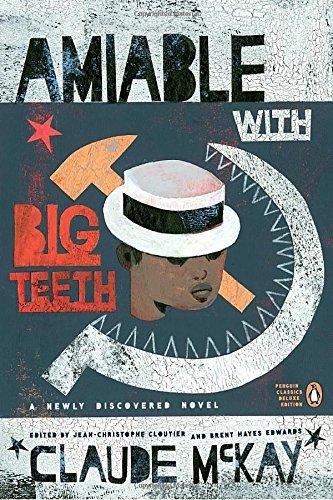

Shortly after I announced the deal for my first book (a primer on how to have more productive conversations on race), a friend posted a link on my Facebook page. With a joking comment along the lines of “Oh no! Looks like Rachel beat you to it!” she linked to an article announcing that Rachel Dolezal would also be publishing her first book on race, In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World. Throughout the week, at least five other friends sent me similar links with similar comments. A look through my social-media feeds showed that I was not alone. Black women writers around the country were all being sent links to articles on Dolezal’s book deal—the memoir of a black woman whose claim to fame is… not being actually black.

INTERVIEW: Ijeoma Oluo (left) with Rachel Dolezal and her son in their kitchen. RAJAH BOSE

“Do you mind if I fold laundry while we talk? Then we’ll go down to the art studio later and look at some of my work,” Dolezal says to me after I arrive at her home.

The laundry basket is already sitting in front of the fireplace ledge. Dolezal takes a seat and begins folding while I dig my notebook out of my backpack and set up my recorder. The scene is eerily normal. The woman who has been at the center of a controversy that has captivated the country for two years is doing chores and lovingly soothing her toddler after he falls down while trying to pick up a toy. Dolezal asks almost defensively if I have read her book, and when I say yes, she looks visibly relieved.

With the din of the television set playing in the background, and with occasional interruptions from her busy toddler, Dolezal and I begin talking.

She has just returned from New York City where she had done the rounds during a media tour for her book, appearing in a Facebook Live interview for the New York Times and giving interviews to Vice and the Today show.

She is currently jobless and spends her days looking after her sons, ferrying them to school and appointments. She braids hair for cash and is still looking for work. Her rental house is a month-to-month lease. “Hopefully, after the book release and this round of media, maybe everybody’s questions and curiosities will be satisfied and then I can reintegrate into society,” she says with a smile.

We visit Dolezal’s studio. She is, in all honesty, a very talented painter. The majority of her paintings feature black people. Other than the paintings of her children, most of the black people depicted appear to be dressed as slaves or tribespeople. Breaking this pattern was a series of portraits hanging on the wall of Dolezal herself. They were done Warhol style, each painting duplicated in a different color. Dolezal explains them to me: “You know, people are always saying to me, ‘Rachel, I don’t care if you are red, green, blue, or purple,’ so I decided to paint myself as red, green, blue, or purple.”

Dolezal chuckles as she says this, as if it is the most clever and original idea anybody has ever had. I don’t know how many times a white person has told me that they don’t care if I’m “red, green, blue, or purple” when they are trying to explain to me just how “not racist” they are—I’ve lost count. I do know that I’ve rolled my eyes every time. As my brother Ahamefule said to me once, “They may not care if I’m red or green or blue or purple—but they sure as hell care that I’m black.”

I ask her specifically about the problematic sections of the book, explaining that her description of falling in love with blackness based on a National Geographicand a Sports Illustrated seems fetishizing to me.

“As a black person, as a kid,” I say, “I remember National Geographic being something that was used to mock me regularly. A lot of the images of black people in National Geographic have been incredibly fetishizing over the years. Is there a reason why you chose the language that you chose? Because honestly, if anybody came up to me and said their first encounter with blackness was through National Geographic, and they loved it, I would end the conversation immediately.”

Dolezal seems offended I would even ask that, reminding me that she was writing about her experience with blackness as a child. “Well, my older brother was fetishizing black women in National Geographic,” she says, looking at me curiously as she folds clothes. “And I talk about that [in the book]. I felt like my gaze was more humanizing, and more of, again, black is beautiful, black is inspirational. I had a different gaze than he did.

“I understand National Geographic has been exploitative. I understand that. But as a 5- or 8-year-old child, looking at images of people, you’re not looking with a doctoral degree of sociology and anthropology and parceling this stuff apart. You’re just… you’re looking at representations of the human experience.”

I try to clarify that it is the fact that she thinks that her connection to blackness represented via National Geographic, no matter how inspirational, could be authentic is itself the problem: “But you are looking at representations crafted by white supremacy. I mean, it’s not actually black people you are looking at.”

“Just like when people are watching TV,” Dolezal says in her defense. Then she seems to remember the interviews in which she had bragged that growing up without television saved her from viewing blackness through a white lens, and her tone changes and sounds almost bitter.

“In that sense, maybe I wasn’t entirely sheltered from the whole propaganda,” she sighs. “Or whatever.”

There was a moment before meeting Dolezal and reading her book that I thought that she genuinely loves black people but took it a little too far. But now I can see this is not the case. This is not a love gone mad. Something else, something even sinister is at work in her relationship and understanding of blackness.

There is a chapter where she compares herself to black slaves. Dolezal describes selling crafts to buy new clothes, and she compares her quest to craft her way into new clothes with chattel slavery. When I ask what she has to say to people who might be offended by her comparing herself to slaves, Dolezal is indignant almost to exasperation.

She is done folding clothes.

“I’m not comparing the struggles, okay? Because I never said that my life was the same. I never said that it was the equivalent of slavery, of chattel slavery. I did work and bought all my own clothes and shoes since I was 9 years old. That’s not a typical American childhood life,” she says. “I worked very hard, but I didn’t resonate with white women who were born with a silver spoon. I didn’t find a sentence of connection in those stories, or connection with the story of the princess who was looking for a knight in shining armor.”

DOLEZAL’S BOOK: Is there a copy of Black Like Me on the shelf? RAJAH BOSE

She almost spits out the last sentences.

I am beginning to wonder if it isn’t blackness that Dolezal doesn’t understand, but whiteness. Because growing up poor, on a family farm in Montana, being homeschooled by fundamentalist Christian parents sounds whiter than this “silver spoon” whiteness she claims to be rejecting.

Dolezal feels she is different from others who would genuinely compare their hardships to slavery: “But those people are not aware, they haven’t been black history professors,” she says with a voice trembling with indignation.

I want to remind Dolezal that she is a former black history professor who has degrees in art, not black history, African history, or American history, but I don’t. I’m trying to not get kicked out of her place early.

It’s only been an hour, and I still need to ask The Question.

Dolezal has argued many times that her insistence on black identity will not only allow her to live in the culture that she says matches her true self, but will also help free visibly black people from racial oppression by helping to destroy the social construct of race.

I am more than a little skeptical that Dolezal’s identity as the revolutionary strike against the myth of race is anything more than impractical white saviorism—at least when it comes to the ways in which race oppresses black people. Even if there were thousands of Rachel Dolezals in the country, would their claims of blackness do anything to open up the definition of whiteness to those with darker skin, coarser hair, or racialized features? The degree to which you are excluded from white privilege is largely dependent on the degree to which your appearance deviates from whiteness. You can be extremely light-skinned and still be black, but you cannot be extremely or even moderately dark-skinned and be treated as white—ever.

By turning herself into a very, very, very, very light-skinned black woman, Dolezal opens herself up to be treated as black by white society only to the extent that they can visually identify her as such, and no amount of visual change would provide Dolezal with the inherited trauma and socioeconomic disadvantage of racial oppression in this country.

I ask her some easy questions, but she answers them with increasing irritation. When we have been together for three hours, I feel it’s time to ask The Question.

It’s the same question that other black interviewers have asked her. A question she seems to deeply dislike—so much so that she complains about the question in her book. But even in the book, it’s not a question she actually answers: How is her racial fluidity anything more than a function of her privilege as a white person?

If Dolezal’s identity only helps other people born white become black while still shielding them from the majority of the oppression of visible blackness, and does nothing to help those born black become white—how is this not just more white privilege?

Dolezal takes issue with the idea that racial fluidity only travels one way: “Well, I would respectfully disagree that it only goes one way,” she says. “I meet people all the time who went the other way. I meet people who have passed or identified as Latina their entire life who were born categorized as black. Who pass white and have a black parent because that’s how they look or that’s how they have kind of come to look.”

Stories of people of color “passing” for white have been well known since the time of slavery. Almost any person of color in the United States has a relative in the past or present who has “passed” for white. But “passing” was a ticket out of the worst injustices of racial oppression that has been open to only a select few. The history of “passing” in the United States is a story filled with pain and separation. It has never been a story of liberation in the way in which Dolezal is trying to describe it.

I point out that there is a difference between Dolezal’s claim of racial liberation and the forced denial of race in order to escape oppression.

“I’m only bringing that up because you said it can only go one way and yet it has and still does go the other way,” Dolezal snaps, as if this defense was pulled out of her and its limitations are my fault. But not only have I heard her invoke the historical passing of light-skinned people of color in previous interviews when any question about the one-way street of her racial fluidity was brought up, she even included this argument in her book. She has had plenty of time to come up with a better answer to that question.

I try one more time to get an answer to this question, but from a different angle: “Where does the function of privilege of still appearing to the world as a white person play into this and into your identity as affiliating with black culture?”

Dolezal seems to struggle for a moment before answering: “I don’t know. I guess I do have light skin, but I don’t know that I necessarily appear to the world as a white person. I think that since the white parents did their TV tour on every national network, some people will forever see me as my birth category, as a white woman. But people who see me as that don’t see me really for who I am and probably are not seeing me as a white woman in some kind of a privileged sense. If that makes sense.”

It doesn’t.

I am nothing if not stubborn, so I clarify my question: “I mean, if you were walking down a street in New York, just as an anonymous person, to a lot of people you would appear as a white woman. There’s a function of privilege to that, right? The way in which you would be able to walk through the street, how people would interact with you, the level of services you would receive, your ability to get a cab, all of that would be impacted. Does that privilege factor into your identity?”

Dolezal looks at me as if my question is completely ludicrous: “Well, I understand your question, but once again, that’s not what I experience. I don’t experience people treating me as a white woman in New York or elsewhere, an anonymous white woman. That’s what I’m trying to explain. People either treat me like a freak because I’m the white woman that pretended to be black in their eyes or treat me as a light-skinned black woman. That’s how people see me.”

I’m confused as to whether Dolezal is claiming that she’s never seen as white because she is simply recognized as Rachel Dolezal wherever she goes, or if she doesn’t “look” white to strangers because her physical appearance is not that of a white woman.

I’m slightly shocked that this is an argument she would make in person. Maybe in a dusty Eastern Washington town like Spokane, where only 2 percent of the people are black, something as “exotic” as box braids might be enough to convince the locals that you are not white, but I cannot imagine this working elsewhere. I’m looking right at her. I know what white people look like. I decide to say so.

“Really? Like if you don’t say, ‘I’m black…’ because I’ve read a lot of interviews with other people who said when they first encountered you, people who’ve worked with you, that they automatically assumed you were white until you had asserted otherwise, vocally. I personally… like if I were to run across you in the street, I would assume that you were white.”

Dolezal sighs and looks at me as if I am truly all that is wrong with America. “Well, I guess it’s like in the eye of the beholder.”

It is obvious by then that Dolezal does not like me, but I don’t appear to be alone in that feeling. Throughout our conversation, I get the increasing impression that, for someone who claims to love blackness, Rachel Dolezal has little more than contempt for many black people and their own black identities.

The dismissive and condescending attitude toward any black people who see blackness differently than she does is woven throughout her comments in our conversation. It is not just our pettiness, it is also our lack of education that is preventing us from getting on Dolezal’s level of racial understanding. She informs me multiple times that black people have rejected her because they simply haven’t learned yet that race is a social construct created by white supremacists, they simply don’t know any better and don’t want to: “I’ve done my research, I think a lot of people, though, haven’t probably read those books and maybe never will.”

I point out that I am a black woman with a political-science degree who writes about race and culture for a living, who has indeed read “those books.” I find her blanket justification of “race is a social construct” overly simplistic. “Race is just a social construct” is a retort I get quite often from white people who don’t want to talk about black issues anymore. A lot of things in our society are social constructs—money, for example—but the impact they have on our lives, and the rules by which they operate, are very real. I cannot undo the evils of capitalism simply by pretending to be a millionaire.

It’s clear I have pushed her to the edge of frenzy, so I decide to discuss something about the book that will not push her over that edge. I talk to her about the foreword by her adopted dad, Albert Wilkerson Jr. It’s sympathetic. “You have a community that has stuck by you through this,” I say. At that point, she breaks down and starts crying.

RAJAH BOSE

For a white woman who had grown up with only a few magazines of stylized images of blackness to imagine herself into a real-life black identity without any lived black experience, to turn herself into a black history professor without a history degree, to place herself at the forefront of local black society that she had adopted less than a decade earlier, all while seeming to claim to do it better and more authentically than any black person who would dare challenge her—well, it’s the ultimate “you can be anything” success story of white America. Another branch of manifest destiny. No wonder America couldn’t get enough of the Dolezal story.

Perhaps it really was that simple. I couldn’t escape Rachel Dolezal because I can’t escape white supremacy. And it is white supremacy that told an unhappy and outcast white woman that black identity was hers for the taking. It is white supremacy that told her that any black people who questioned her were obviously uneducated and unmotivated to rise to her level of wokeness. It is white supremacy that then elevated this display of privilege into the dominating conversation on black female identity in America. It is white supremacy that decided that it was worth a book deal, national news coverage, and yes—even this interview.

And with that, the anger that I had toward her began to melt away. Dolezal is simply a white woman who cannot help but center herself in all that she does—including her fight for racial justice. And if racial justice doesn’t center her, she will redefine race itself in order to make that happen. It is a bit extreme, but it is in no way new for white people to take what they want from other cultures in the name of love and respect, while distorting or discarding the remainder of that culture for their comfort. What else is National Geographic but a long history of this practice. Maybe now that I’ve seen the unoriginality of it all, even with my sister’s name that she has claimed as her own, she will haunt me no more and simply blend into the rest of white supremacy that I battle every day.

Before I left Dolezal, I remembered that my editors had told me to make sure the photographer got a few pictures of us together. We were both sitting at the kitchen table, which provided an ideal photo opportunity.

The natural light from the sliding door by the kitchen was great for photography, but with our current seating arrangement, that light was falling on me and leaving her in the shadow. It is standard practice to have the interviewee sit in the best light, so I asked her to switch seats. The photographer thanked me for the suggestion, and I stood to allow Dolezal to take the chair I had been in.

Dolezal looked at me with a smirk and said accusingly: “Then you’ll look darker and I’ll look lighter, because the light’s on me. I get it.”

I realized that like all other black people who had challenged Dolezal, I had been written off as a bitter, petty black woman. She was concerned that the wrong lighting would make her look white.

She could not see that there was no amount of lighting that would make her look whiter than that interaction had. Perhaps that itself was the secret to the power of the Dolezal phenomenon—the overwhelming whiteness of it all.

This article has been updated since its original publication.