October 14, 2015

Come On Up,

Sweetheart

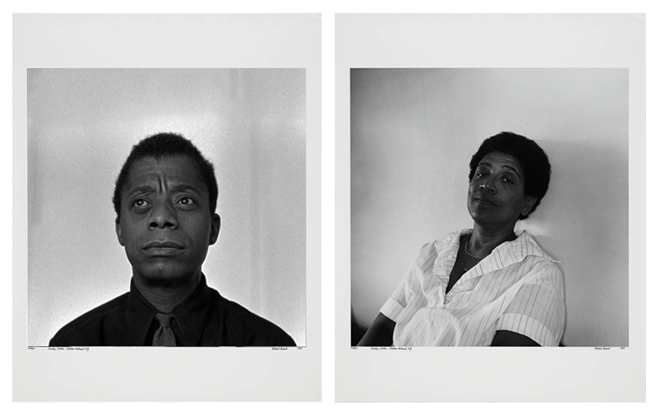

James Baldwin’s Letters to his Brother

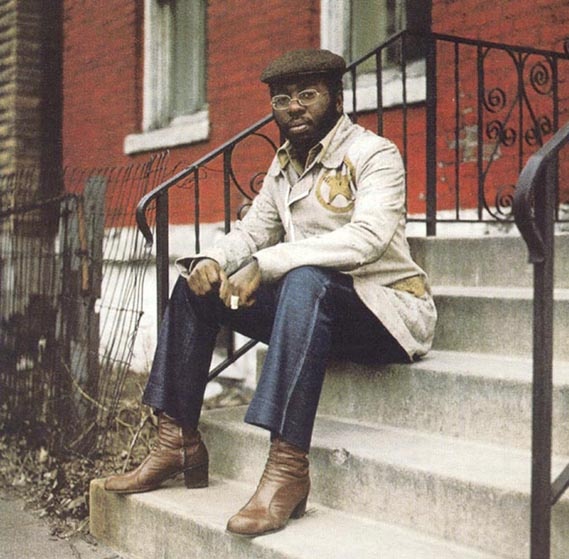

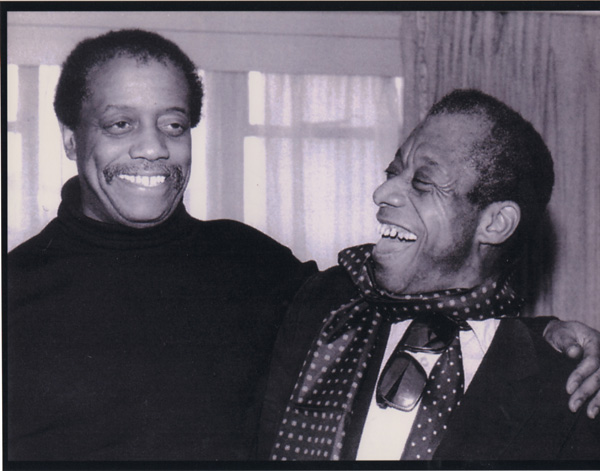

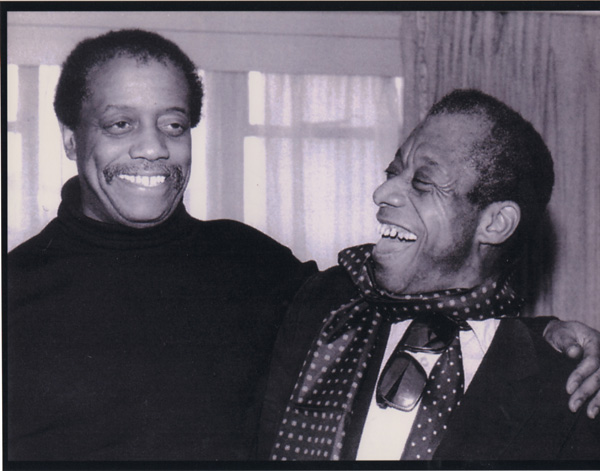

David Baldwin with James Baldwin in the 1980s. Photo courtesy of Carole Weinstein.

BY ED PAVLIĆ

“What’s happening to we?”

—SZA, “Warm Winds” (2015)

“Incoherence” was James Baldwin’s favorite word to describe Americans’ chronic inability to apprehend their own experience. One finds it scattered across his works. “Because I am an American writer,” he says in “Notes for a Hypothetical Novel” (1960), “my subject and material has to be a handful of incoherent people in an incoherent country.” The term coded the gap between “one’s image of oneself and what one actually is,” and the failure to connect to the lives of loved ones, neighbors, strangers. Often he laid the word like a lace drape across portraits of puzzlement at that vexed and elastic quantity, an American “we.” In a speech at Kalamazoo College in 1960, he sketched the question beneath the transracial skin of American incoherence: “The question is not what we can do now for the hypothetical Mexican, the hypothetical Negro. The question is what we really want out of life, for ourselves, what we think is real.”

Baldwin’s American “we” has been read to mean white people, and it often does; but close attention shows that his sense of an American collective didn’t obey what he called the “artificial walls” of racial division. In the “The Uses of the Blues” (1964) he rejects those walls: “We came from Europe, we came from Africa, we came from all over the world. We brought whatever was in us from China or from France.” “We are part of each other,” he insisted in the Kalamazoo speech. “What is happening to every Negro in the country at any time is also happening to you. There is no way around this.” To white people this may have read as a warning, but it reads just as well as a challenge to all people grappling with the American myth of the individual. Baldwin knew that the truth about “what one actually is” involves many, a plurality.

In “Paris Letter: A Question of Identity” (1954), Baldwin argued that one obstacle to our coherence was a distinctively “American simplicity,” which was convinced that the search for the real must involve the “imagination not at all” and led to “a total confusion about the nature of experience.” Our “national self-image” of “hard work and good clean fun and chastity and piety and success . . . leaves out of account, of course, most of the people in the country, and most of the facts of life” and “has almost nothing to do with what or who an American really is.” Beneath this “conqueror image” lie “a great many unadmitted despairs and confusions, and anguish and unadmitted crimes and failures.”

Baldwin implored us to imagine the collision between impersonal questions about “what” one is in history and personal ones about “who” one is in private. Without that collision, history’s so-called factual, “what” questions remain abstract and blunt, while the so-called personal, subjective “who” questions are condemned to be “irrelevant details.” Without this texture behind historical events, he explained in “This Nettle Danger” (1964), “we don’t know what the person—or, perhaps in this context, one should rather say the subject—makes of them, what he sees in them, what he takes from them.” “Without knowing this,” he concludes, “we know nothing, experience being less a matter of what happens than to whom: experience is created out of the effort to create oneself.”

Apart from his published work over four decades, Baldwin left his own copious and conflicted record of his experience creating himself. Between the late 1940s and the mid-1980s, he carried on an increasingly dense and complex correspondence with his youngest brother, David. Many of these letters survive—some 120 of them, amounting to about 70,000 words. They give an unprecedented picture of his life and work, an epistolary autobiography: they bristle and crackle with the trials, dangers, errors, mistakes, and triumphs of one of the most important literary figures of the twentieth century. Yet, as is the case with all of Baldwin’s correspondence and unpublished materials, they are fiercely protected by Baldwin’s family. Hilton Als wrote in 2001 that “there is one great Baldwin masterpiece waiting to be published, one composed in an atmosphere of focused intimacy, and that is a volume of his letters, letters his family does not want published.” The estate disallows even those few who’ve seen the letters from quoting them.

Baldwin’s correspondence with his youngest brother, David, gives an unprecedented picture of his life and work, an epistolary autobiography.

So it was unusual when, in July 2010, Baldwin’s sister and literary executor, Gloria Karefa-Smart, invited me to her house to discuss my request to read these letters and write about the story they tell. One summer morning in D.C., I found myself walking up to her home, nervous, when I heard her call to me out of the window, “Come on up, sweetheart.” Moments later I stood in front of a table—an altar, really—above which was placed a shimmering portrait of Baldwin done by his first artistic mentor, Beauford Delaney. Below were a few candles and photos of generations of Baldwin’s family. Gloria introduced me: “Family, this is Ed, he’s here because he loves Jimmy’s work.” I can’t remember if she told them that she thought I’d “keep the faith” or if she asked me to promise to keep the faith, but whether it was said out loud or spoken silently by my heart, I do remember promising.

Standing in Gloria’s living room, I thought of Hall’s description of Julia’s house from Baldwin’s final novel, Just Above My Head (1979): “Julia’s den is her secret place—in the biblical sense; and no one enters without being asked. . . It’s a meditation room, says Julia, and that’s not bullshit. You feel a concentrated human passion in the room.” Gloria’s own room reflected the “concentrated human passion” her brother had brought into the world. It is possible that she and I both trusted that more than we trusted each other.

I had a semester off from teaching in Georgia. I’d proposed to Gloria that I’d live with my in-laws in Maryland, drive down to D.C. and spend a few hours each day reading in this room, taking notes on the letters and whatever else she happened to share with me. Yet when I arrived to plan out the routine, Gloria said it’d be easier if I just took the files home with me. So it was that I walked out carrying folders filled with letters that—I’d learn—much of the intellectual world was clamoring to see. I remember Gloria saying, as I left, “go ahead, I haven’t read them, don’t have the soul-stamina, but you can handle it.”

Back in Georgia I locked my office door and sorted the letters by decade. Many were undated. Some had a month and date but no year; some had a year and a day, but no date or month. Some referred to private or historical events—a birthday, a protest march, a performance.

I’d read all of Baldwin’s published work, collected and uncollected. In order to cross-reference, I read and reread the major studies. Still, I was unprepared for this intensely private encounter with Baldwin’s experience. His voice on the page can produce a uniquely electrical sense of connection with his reader. Some love it; others recoil from it. Others simply say, “It saved my life.” But encountering the letters was different. I was typing the real-time record of Baldwin’s attempts to save his own life and then risk it again and again by flinging himself into the next work he thought might resonate within and radiate between people. Himself, and his youngest brother, but also people he’d never meet, like me.

When we first began corresponding, I’d mailed Gloria copies of all my books of poems and the one scholarly work I’d done. When we met in person, I remember her intoning, “well, maybe it takes a poet?” Poets amplify nuance and focus on details others pass by. Maybe my sense of the pressure recorded in Baldwin’s letters owed to their turbulent, amplified clarity, the coherence of poetry. Or maybe it was the secrecy, the privacy. Maybe it was the fact that they were written in love, and demonstrate, in ways unlike anything I’d encountered, the active craft of love, between brothers, among family. They’d been held in secrecy by the love of their sister. In them, David was told things in confidence: I haven’t told mama yet so don’t you tell her, his older brother would instruct. A few letters concluded with the thought that it might be best if the pages were promptly burned.

Yet they weren’t, and I typed my way through the decades. I crossed the early ’50s when, living in Switzerland and France on meager fees for essays and articles, Baldwin still avoided sharing with his brother the details of his “private” or “lonely” life. Most of these letters were about nascent successes and money troubles. He told himself he’d gone to Paris to make it as an artist and save his family from poverty, but more than half of these early letters included thanks to David for sending money—cash in carbon paper sent to American Express in Paris—or requests for $20 or $50 more, and quick. In May 1953, with his first novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain, accepted but not yet published and the meager advance spent, he wrote from Paris to say that Time had photographed him; he’d had to borrow money to get to the photographer’s office.

In November 1955, he wrote David from London, broke. His second novel, Giovanni’s Room, was done, unpublished, and viewed as offensive by his agent. Baldwin was thirty-one. David was almost twenty-four. He offered David a way to back off from their intensifying relationship, and, by implication, from the impending controversy over a novel that featured erotic relationships between men. He was no longer the big brother to a boy; they were now both men and, possibly, David wasn’t enamored of him as he had been when he was little. But that didn’t happen. The two would grow closer throughout the decades until Baldwin’s death in 1987, in France, with his brother by his side.

He told his brother he’d promised their ancestors he would keep the faith: he knew personal success wasn’t the measure of the experience he was creating.

He returned to the United States in the summer of 1957 and toured the South. On October 11, he wrote David from Tuskegee in a panic, unable to sleep. He’d toured Montgomery and had ridden the recently desegregated buses, with armed, hostile white drivers. He described white hatred steaming out of the pavement. A week later, from Birmingham, in even worse shape, he’d write his friend Mary Painter in D.C., saying that the American South was the saddest place he’d ever been in, even sadder than Germany and Spain after World War II. Then, thinking of a mass meeting led by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy that he’d attended, he thought he probably hadn’t met the European counterparts of these southerners because, by the time he’d arrived in Europe in 1948, they’d already been exterminated. Wondering if that impression was too extreme, he affirmed that it would be impossible to overstate the pain and peril he was witnessing. Closing the letter, he said that the dishwasher at the A.G. Gaston Motel, where he was staying, was taking him to interview a man, “Judge” Aaron Edwards, who’d been castrated by a white mob on Labor Day. Both to his brother and to his close friend in D.C., Baldwin stressed his unsettling feeling that he shouldn’t stay in the Deep South for long. And, somehow, he postponed his breakdown until he arrived back in New York City. Nonetheless, over the coming years, as the violence mounted, he’d make several return trips.

By 1959 he was stymied again in his progress on Another Country. I typed his letter from Stockholm on October 3, 1959, explaining the novel had come back into focus while he interviewed Ingmar Bergman at his studios outside the city. Envying the efficiency, for men, of the heterosexual domestic arrangement, or maybe just envying Bergman, the letter rehearsed the possibility of getting married but concluded it would be best to restrict the number of lies in his life to those that really couldn’t be helped. He was looking for a way, an artistic method, to join who he was to an emerging politics in the American South and in the anti-colonial movements around the world. He sensed those forces could draw him beyond the era’s confining, individual model of artistic craft. In the late ’50s, most would have already called Baldwin’s career a success. For his part, he knew that the structure of such success could only reinforce “the prison of [his] egocentricity.” He told his brother he’d promised their ancestors he would keep the faith: he knew personal success wasn’t the measure of the experience he was creating.

Among the letters was a postcard Baldwin sent to David in 1962 while he traveled in Sénégal with Gloria. In “The White Problem” (1964), Baldwin would remember standing in the slave fort on Gorée Island. He looked over the Atlantic from an opening in the stone wall and “tried to imagine what it must have felt like to find yourself chained and speechless, speechless in the most total sense of the word, on your way where?” While based in Turkey, in June 1965, he sent another postcard, from Vienna, where his play, The Amen Corner, had been a hit. There had been over thirty curtain calls. He told David the city hadn’t seen anything like it since the Ottomans were at the gates in the seventeenth century. On July 7, 1966, David wrote Baldwin—one of the rare letters of David’s I saw—telling him that the new word was “Black Power” and that the established leaders (Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King, Jr.) and organizations (SNCC and CORE) were running for cover. In responses written that summer, Baldwin explained to his youngest brother what he considered the hopeless and self-destructive limitations of the new politics as it emerged. Despite his reservations—or, really, because of them—he would engage the younger activists personally and politically over the coming years.

I paused on a letter from March 10, 1968. King was still alive. In fact, Baldwin would see him in Los Angeles the next week at a fundraiser for The Washington Poor People’s Campaign hosted by Marlon Brando. In the letter, addressed to David and his sister Paula, both living in London at the time, Baldwin listed titles of Aretha Franklin songs as they played on the record player. It was 3 a.m. in Palm Springs; he was poolside and running out of cigarettes. He’d taken a break from his work on the script for a film about Malcolm X for Columbia Studios. From the titles and their order, I realized he was playing Side 2 of Aretha Arrives (1967). I played the album myself. Listening over Baldwin’s shoulder, I heard a response to “speechlessness in the most total sense of the word,” to the view west from Gorée Island, the historical view Baldwin had imagined over the Atlantic in 1962. Baldwin marveled at Aretha’s ability to voice a condition at once historical and personal. What she sang was artistic and private, but also revolutionary and public. This was coherence. He wanted to learn to write like that, he told David and Paula.

Baldwin marveled at Aretha’s ability to voice a condition at once historical and personal. This was coherence.

Amid flashes of fear, promise, murder and despair, I moved through the tangle of accumulating commitments, F.B.I. surveillance, and lethal threats from the late ’60s and early ’70s. Eldridge Cleaver, Amiri Baraka, and other nationalist figures derided Baldwin publicly but privately appealed to him for support, which he often gave. Faced with the reality that what he—and many others—were attempting to do was beyond the realm of the reasonable, likely beyond that of the possible, Baldwin told his brother that he’d rearrange—almost reinvent—himself around the necessary. If what people were was being rounded up for slaughter, jailed and imprisoned in unprecedented fashion, he thought, the somewhat more subtle question of who they were would be killed, too. It was a tactical and temporary re-orientation of priorities.

Then, another abrupt turn: his departure in July 1969 from Hollywood. He moved back to Istanbul where he lived with his lover Alain and, for a time, again, with Beauford Delaney. Still, he was far from disengaged. In September 1969, in fact on the day before the trial against the Chicago 8 began, he sent David a copy of a letter (and a check) he’d sent to Susan Sontag, who served with Kathleen Cleaver as national treasurer of The Committee to Defend the Conspiracy, a campaign to defend the men on trial. Baldwin asked that they consider him part of the movement to free the activists. In Istanbul, he was directing John Herbert’s play, Fortune In Men’s Eyes, and described standing backstage watching the cleaning woman in the theater as she watched the actors rehearsing.Wondering what she would think of the street language and homoerotic energy of the play, he half-jokingly feared she would tell her brothers and he’d be confronted one day after rehearsal by a mob who’d stone him and chop off his head. He told David that the old woman eventually greeted him back stage with great respect and with tears in her eyes.

Entering the 1970s, I encountered thousand-word paragraphs recounting the years-long, quasi-legal financial battle Baldwin fought—often with the alarmed, half-consent of his family—with his publishers. While the Dial Press limited his income and allocated him stipends minus (considerable) expenses, he needed a quarter million in cash to buy his house in France. When the press refused to renegotiate, he eventually got the down payment by selling—most likely athwart his contracts in the States—an unwritten novel to a French publisher for $50,000. As publishers threatened him and his agents in the United States, Baldwin, who often enough claimed he couldn’t add, played out the role of the anti-paternalistic, black-power-inflected and by-any-means-necessary businessman. Finally, when Baldwin stopped taking their calls, Dial sent a new editor, Richard Marek, to France to deal with the enraged and intransigent star author. Marek made his way to Nice to meet Baldwin for lunch at the Hotel Negresco. It was June 28, 1972, a Wednesday. Baldwin arrived, took a seat, and announced, “This nigger ain’t going to pick another bale of cotton.” After which, Marek recalled to Bill Weatherby, “We talked about Dostoevsky, politics—everything. . . By the end of that lunch I had a ‘pass’ from him which guaranteed me safe passage when blacks took over New York. ‘If you get it out of your wallet in time, you may be alright,’ he told me.” And, in short order, Baldwin had a new, two-book deal that paid him what he’d thought his books were worth in the first place.

In June 1973, Baldwin found himself in what he called a marriage to a married Italian painter, Yoran Cazac, whose youngest son had been christened, that Easter, as Baldwin’s godson. The relationship transformed Baldwin’s sense of intimacy. Meanwhile, as international fugitive Eldridge Cleaver made contact, eventually sending an envoy with tape-recorded messages asking for help and for money, Baldwin planned his trip to Los Angeles, where he’d meet Ray Charles to finalize the script for their performance of “The Hallelujah Chorus” in Carnegie Hall as part of the Newport Jazz Fest on July 1. From the stage, he’d tell the packed house that in order to get to Hallelujah, one must first accept life’s risks and contradictions and say Amen to all of it: “Amen is the price.” Redacting any part of life led to incoherence.

The story turned again and I found him writing, in May 1974, to tell David to inform the family that death threats wouldn’t dissuade him from returning to the States to tour with his fifth novel, If Beale Street Could Talk. In a deeply personal note that took him several drafts to complete, he said that amid the mounting perils of the post–civil rights era, he’d sooner expose himself to the possibility of betrayal than embrace paranoia; if assassinated, he held, at least it would be a reality inflicted upon him by a real person. He regretted the pain this would cause them, but this was a possibility they’d have to accept, even embrace. He’d sooner be physically dead than endure a spiritual death by populating his life with ghosts and scurrying about in fear of their shadows. He told David that the pact he had made with their ancestors impelled upon him this way of being. As he’d say years later, one struggled against incoherence by walking toward one’s terrors.

There are fewer letters from the late ’70s and ’80s. By then Baldwin had spent time living and traveling with David. His house in St. Paul de Vence was now a center of gravity unlike any he’d known in his life. Yet even amid his community of friends, helpers, family, and lovers, the turbulent collisions between who and what people were persisted. In the face of the world at its worst, and with episodes of hideous violence in South Africa, Iran, and at home in Harlem, and in ways he thought maybe only a black Westerner might at that time be able to sense, he affirmed that hell was notother people. One long letter from October 1975 describes the deeply affirming and yet troubling connections between his family and the characters in Just Above My Head, a connection he’d never attempted before. He also recounts a long dinner with two famous friends, Harry Belafonte and French actor Yves Montand. The three ate at Baldwin’s favorite haunt in St. Paul de Vence, La Colombe d’Or, and discussed the unlikelihood of their successes, but Baldwin privately wondered at the long route they’d each had to travel to be his friends. Montand had become a brother, Baldwin told David, after treating him for years with terrified reverence, a distanced and possibly outraged awe, as if Baldwin had somehow always just escaped a lynch mob. And he considered privately the long distance he felt Belafonte must have had to travel in order to overcome his visceral aversion to Baldwin’s sexuality.

The late letters were meditations on Baldwin’s deepening sense that human peace could never be pursued through divisions.

These late letters were meditations on Baldwin’s deepening sense that human peace could never be pursued through divisions; human freedom, however pressurized and perilous, was a function of essential connections. Personally, he queried the distinctions between love and envy, pride and vanity, the insidious ways that personal devotion destroyed the alchemy of parity and contest that love needed to remain challenging, dangerous, and alive. Politically, while he worked on “RE/member This House,” a memoir he wouldn’t live to complete about his friendships and collaborations with Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., he mused upon the end of what he considered the abstract and mathematical cruelty of revolutions. As he wrote in one of his last published pieces, “To Crush the Serpent” (1987), the final, lyrical code of Baldwin’s career was that “Complexity is our only safety and love is the only key to our maturity.” Sweeping away all orthodoxies in a single phrase, he concluded: “And love is where you find it.”

When I began working with the letters, I thought I was searching for the story that matched the personal Jimmy to the public James. That distinction was familiar to many, and the letters certainly show the complex relationship between those two facets of his life and work.

Yet I discovered that the question of who Baldwin was had at least two other answers, beyond Jimmy and James. Over the years, he described his work alone at the keys to David. He worked from midnight to dawn, ice gone to water in a neglected glass of scotch and often enough in the midst of music playing in his study—in what he called his “dungeon”—and in his memory and imagination. Again and again, he maintained that everything was in question in that space; during those hours, even he didn’t know his name. The radically open-ended quality of his solitude at work was a route toward rather than away from other people. Baldwin describes this space, its terrors and its importance, in his letters to David in ways unlike anything I’d seen.

I also noticed that he signed almost all of the 120 letters “Jamie.” I’d never seen that name referring to Baldwin before, though he does use it to name a character in the short story “The Man Child” (1965). It also served as a kind inside joke. After my work with the letters, when I encountered the character Jaime in If Beale Street Could Talk, immediately I saw it as Jamie. Jaime,—“I love” in French—appears to drive Sharon Rivers from the airport. The origin of the name becomes clear enough in light of a letter written in June 1972, as he was writing Beale Street, telling David that he was taking driving lessons (soon aborted after a minor crash) for the sole purpose of picking David up from the airport in Nice and driving him up the mountain to St. Paul de Vence. After that, Baldwin said, he’d go back to driving his typewriter.

I decided Jamie was a name for a particular dimension of his life and love, his role as elder brother, almost surrogate father, uncle, and son. As I read back and forth across the decades, I could see that that role had lain like a foundational loam beneath everything else. Somewhere he’d had to decide that he’d do it all for them; despite his constant mobility, his need for fame and an unnamed solitude in which to work, the truth was that he’d done much of it with them. In 1979, he’d tell an audience in Berkeley, “we’ve never been alone, that’s the mystery.” Though famously and intensely social as Jimmy, Baldwin would find the primary evidence for the mutuality of human experience in his role as Jamie with his family. It was work done as brother to his sisters and brothers, as son to his mother, and to his father, and as uncle to his nieces and nephews.

These letters enlarge our sense of the man and deepen our sense of possible human courage, commitment, and cooperation. The coherent story of who James Baldwin was is the story of at least four selves: James Baldwin, public figure; Jimmy Baldwin, friend and lover; Jamie Baldwin, son and brother; and an unnamed writer who, in his work, translated himself into a kind of universal human kin. Which is to say that who James Baldwin was was a person dedicated to us all. We.

>via: http://bostonreview.net/books-ideas/ed-pavlic-james-baldwin-letters-brother?utm_content=buffer262fb&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer#.WYHpMOCt-E4.twitter