INCOGNITO

Kalamu ya Salaam's information blog

INCOGNITO

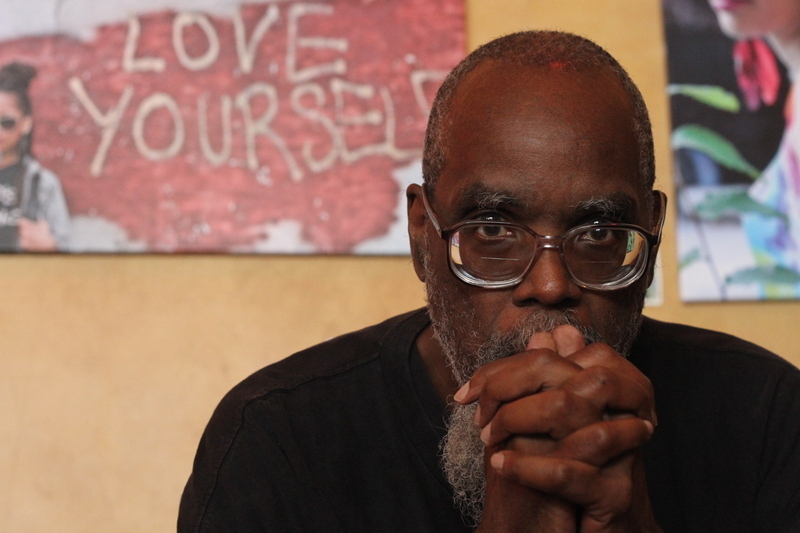

photo by Cfreedom

UNFINISHED BLUES

(featuring Walter “Wolfman” Washington – guitar)

sometimes i never

think of you

other times seems

like i never get through

seasons pass, rain falls

i never think of you

some recorded singer sighs

i wonder how you do

the ache in my heart

got a key

to my mind’s back door

comes and goes

as it please

i don’t miss you all

a the time

just

sometimes

—kalamu ya salaam

Aug 21, 2017

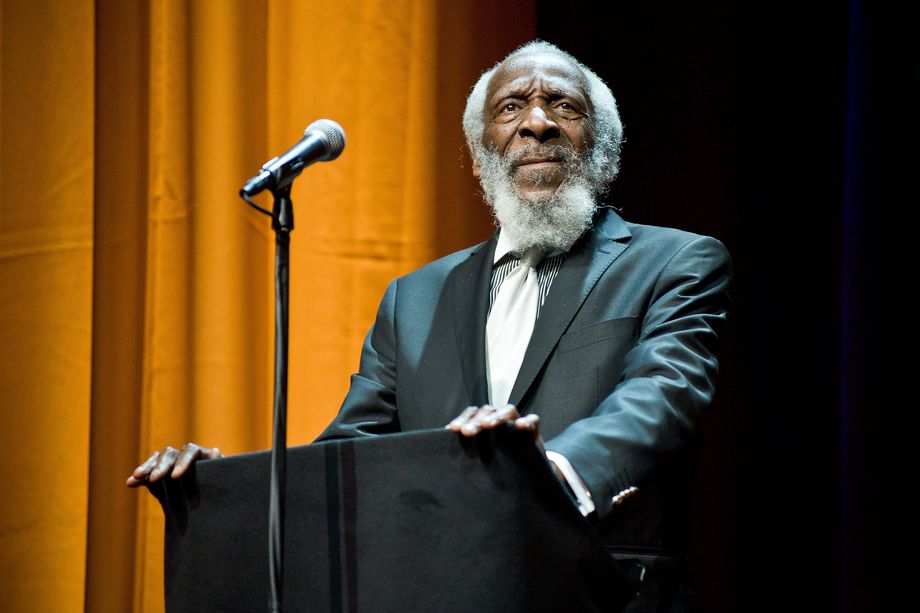

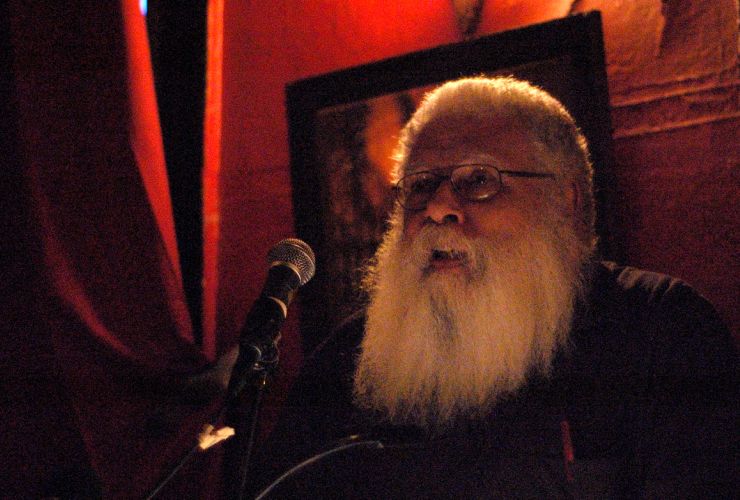

Humorist and activist Dick Gregory at the Roger Ebert Memorial Tribute on April 11, 2013 in Chicago, Illinois. Timothy Hiatt / Getty Images

Humorist-activist Dick Gregory was a man of many words whose fighting spirit helped transform conversations and action around race and justice in an often divided and discriminatory America.

Gregory — who died of heart failure on Saturday, August 18, at the age of 84 after a decades-long career in comedy — was known for his off-the-cuff, no-holds-barred humor. He could captivate any crowd with his cool but passionate demeanor and keen, often unsettling observations, which focused on everything from the Ku Klux Klan to Michael Jackson, a poor black man who grew up “to be a rich white man.”

For one joke, Gregory recalled walking into a restaurant and being told that they “don’t serve colored people.” “Well,” Gregory replied, “I don’t eat colored people.”

His career took shape during the civil rights era, a topic that remained at the center of his comedic identity throughout his life. Breaking out in the 1960s after catching the eye of Hugh Heffner, Gregory became one of the first black comedians to cross over into the white circuit, enduring racist jeers and insults with dignity and disregard — a response he practiced at home with his wife, who rather reluctantly hurled those same words at him to help him prepare.

During that time, Gregory made an unprecedented visit to Tonight Starring Jack Paar in 1961.After initially refusing to appear on the show, he accepted Paar’s offer to perform under a seemingly simple yet groundbreaking condition: Gregory would only perform if he could sit on Paar’s couch after his routine. Gregory’s appearance on The Tonight Show marked the first time a black performer had ever graced those late-night cushions.

He openly refused to shy away from stinging subjects, but often reminded people thathumor was not enough. “Humor can no more find the solution to race problems than it can cure cancer,” Gregory said. “We didn’t laugh Hitler out of existence.”

In a time when dissenting opinion on race and discrimination could put a literal target on your back, Gregory wasn’t just peddling funny. He said it like he saw it, and then he did it, marching for voting rights and performing at benefits for civil rights groups. He was even shot in the leg while serving as a peacemaker during the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles.

It was moments like those — earnest calls to put humor and pleasantries aside when the occasion called for more — that helped make his work onstage that much more resonant.

As Gregory got older, he took some of that biting wit to the stage in a different way, doing panels at festivals and talks to college audiences about his career, his interests, and the evolving face of racism. (He also increasingly dabbled in nutrition theory and conspiracy theories about the long-reaching arm of “the system.”) His life and his work unapologetically ran the gamut, and his panel talk during the 2010 Chicago Humanities Festival is a near-perfect example of the unique and definitive nature of his work.

At one point during the talk, Gregory addressed an audience question about a Southern judge who refused to marry interracial couples, and his response epitomized the comedian and activist’s unyielding but purposeful honesty.

“He didn’t resign,” Gregory told the audience. “He embarrassed the whole state and the whole nation.”

He continued:

There’s a whole lot of things that embarrass us. … This is not just some thug on the corner. This is a judge — with that attitude. But whole lots of Americans got that attitude, and we tolerate it because you can hide your feelings. You don’t have to come out. … Once you flush it out, he’s not the only one. Suppose he would have gone on and married them. He still would have felt that way. … That’s why we got to work to flush this whole thing out.

Gregory’s approach both subtly and unsubtly forced America to look at itself in the mirror and reckon with its ugly side. His life and career were a fine example of the power of speech, and the most ordinary man’s ability turn words into action.

>via: https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/8/21/16177470/dick-gregory-dead-comedy-race-activism

APRIL 12, 2001

Indiana University Press, 231 pp., $29.95

University Press of Virginia, 124 pp., $22.95

When Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865, at the end of four years of civil war, few people in either the North or the South would have dissented from his statement that slavery “was, somehow, the cause of the war.”1At the war’s outset in 1861 Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, had justified secession as an act of self-defense against the incoming Lincoln administration, whose policy of excluding slavery from the territories would make “property in slaves so insecure as to be comparatively worthless,…thereby annihilating in effect property worth thousands of millions of dollars.”2

The Confederate vice-president, Alexander H. Stephens, had said in a speech at Savannah on March 21, 1861, that slavery was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and the present revolution” of Southern independence. The United States, said Stephens, had been founded in 1776 on the false idea that all men are created equal. The Confederacy, by contrast,

is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.3

Unlike Lincoln, Davis and Stephens survived the war to write their memoirs. By then, slavery was gone with the wind. To salvage as much honor and respectability as they could from their lost cause, they set to work to purge it of any association with the now dead and discredited institution of human bondage. In their postwar views, both Davis and Stephens hewed to the same line: Southern states had seceded not to protect slavery, but to vindicate state sovereignty. This theme became the virgin birth theory of secession: the Confederacy was conceived not by any worldly cause, but by divine principle.

The South, Davis insisted, fought solely for “the inalienable right of a people to change their government…to withdraw from a Union into which they had, as sovereign communities, voluntarily entered.” The “existence of African servitude,” he maintained, “was in no wise the cause of the conflict, but only an incident.”4 Stephens likewise declared in his convoluted style that “the War had its origin in opposing principles” not concerning slavery but rather concerning “the organic Structure of the Government…. It was a strife between the principles of Federation, on the one side, and Centralism, or Consolidation, on the other…. Slavery, so called, was but the question on which these antagonistic principles…were finally brought into…collision with each other on the field of battle.”5

Davis and Stephens set the tone for the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War during the next century and more: slavery was merely an incident; the real origin of the war that killed more than 620,000 people was a difference of opinion about the Constitution. Thus the Civil War was not a war to preserve the nation and, ultimately, to abolish slavery, but instead a war of Northern aggression against Southern constitutional rights. The superb anthology of essays, The Myth of the Lost Cause, edited by Gary Gallagher and Alan Nolan, explores all aspects of this myth. The editors intend the word “myth” to be understood not as “falsehood” but in its anthropological meaning: the collective memory of a people about their past, which sustains a belief system shaping their view of the world in which they live.

The Lost Cause myth helped Southern whites deal with the shattering reality of catastrophic defeat and impoverishment in a war they had been sure they would win. Southerners emerged from the war subdued but unrepentant; they had lost all save honor, and their unsullied honor became the foundation of the myth. Having outfought the enemy, they were eventually ground down by “overwhelming numbers and resources,” as Robert E. Lee told his grieving soldiers at Appomattox. This theme was echoed down the years in Southern memoirs, at reunions of Confederate veterans, and by heritage groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. “Genius and valor went down before brute force,” declared a Georgia veteran in 1890. The Confederacy “had surrendered but was never whipped.” Robert E. Lee was the war’s foremost general, indeed the greatest commander in American history, while Ulysses S. Grant was a mere bludgeoner whose army overcame his more skilled and courageous enemy only because of those overwhelming numbers and resources.

Not only did Confederate soldiers fight better; they also fought for a noble cause, the cause of state rights, constitutional liberty, and consent of the governed. Slavery had nothing to do with it. “Think of it, soldiers of Lee!” declared a speaker at a reunion of the United Confederate Veterans in 1904:

You were fighting, they say, for the privilege of holding your fellow man in bondage! Will you for one moment acknowledge the truth of that indictment? Oh, no! That banner of the Southern Cross was studded with the stars of God’s heaven…. You could not have followed a banner that was not a banner of liberty!

The theme of liberty, not slavery, as the cause for which the South fought became a mantra in the writings of old Confederates and has been taken up by neo-Confederates in our own time. The Confederacy contended for “Freedom’s cause,” a veteran told his comrades at an 1887 reunion, “a struggle for constitutional rights against aggression, oppression and wrong.” Other speakers at the same convention said they had “fought for the right of local self government,” for “the idea that liberty in a government like ours is best preserved by restraining central power and giving to the states…all the rights which are not distinctly and absolutely conferred upon the central power.”

These arguments remain alive. On a visit to a Confederate cemetery before she became President Bush’s secretary of the interior, Gale Norton expressed regret that with the Confederate defeat “we lost too much. We lost the idea that the states were to stand against the federal government gaining too much power over our lives.” Senator John Ashcroft, now attorney general, told the neo-Confederate magazine Southern Partisanthat “traditionalists must do more” to defend the Southern heritage. “I’ve got to do more,” he said.6

The Lost Cause view of the origins of the Civil War entered the mainstream of historical writing in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1930 Frank Owsley, one of the foremost Southern historians of his generation, wrote that the Confederacy fought not only for the principles of states’ rights and self-government but also for the preservation of a stable, pastoral, agrarian civilization against the overbearing, acquisitive, aggressive ambitions of the urban-industrial Leviathan growing up in the North. The real issue that provoked secession was not slavery—this institution, wrote Owsley, “was part of the agrarian system, but only one element and not an essential one”—but rather such matters as the tariff, banks, subsidies to railroads, and similar matters in which the grasping industrialists of the North sought to advance their interests at the expense of Southern farmers and planters.7

From the 1930s to the 1950s the most influential interpretation of the causes of the Civil War was that put forth by the “revisionist” school of historians, whose leading figure was Avery Craven. The revisionists denied that sectional conflicts between North and South were genuinely divisive. The differences between these regions, wrote Craven, were no greater than those existing at different times between East and West. Such minor disparities did not have to lead to war; they could have, and should have, been accommodated peacefully within the political system.8 The Civil War was thus not an irrepressible conflict, as earlier generations had called it, but a “repressible conflict,” as Craven titled one of his books. The war was brought on not by genuine issues but by extremists on both sides, especially abolitionists and radical Republicans, who whipped up emotions and hatreds for their own self-serving partisan purposes. The passions they stirred up got out of hand in 1861 and erupted into a tragic, unnecessary war which accomplished nothing that could not have been achieved by negotiations and compromise.

Any such compromise in 1861, of course, would have left slavery in place and would have reinforced the right of slave owners to take their property into the territories. But revisionists considered slavery unimportant; as Craven once stated, the institution of bondage “played a rather minor part in the life of the South and the Negro.”9 Slavery would have died peacefully of natural causes in another generation or two had not fanatics forced the issue to armed conflict. Republicans who harped on the evils of slavery and expressed a determination to rein in what they called “the Slave Power” goaded the South into a defensive response that finally caused Southern states to secede to get free of the incessant pressure of these self-righteous Yankee zealots. Revisionism thus tended to portray Southern whites as victims reacting to Northern attacks; it was truly a war of Northern aggression.

Since the 1950s most professional historians have come to agree with Lincoln’s assertion that slavery “was, somehow, the cause of the war.” Outside the universities, however, Lost Cause denial is still popular, especially among Southern heritage groups that insist the Confederate flag stands not for slavery but for a legacy of courage and honor in defense of principle. When Ken Burns’s PBS documentary on the Civil War portrayed slavery as the root cause of the conflict, the reaction among many Southern whites was hostile. “The cause of the war was secession,” declared a spokesman for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, “and the cause of secession could have been any number of things. This overemphasis on the slavery issue really rankles us.”10 Another Southerner, whose ancestor served in the 27th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, insists that slavery was “only one issue among many that lead [sic] to secession,” and a minor one at that. Of equal or greater importance was the commitment of Confederate Southerners to “states rights, agrarianism,…aristocracy, and habits of mind including individualism, personalism toward God and man, provincialism, and romanticism.”11

The states’-rights thesis has found its way into some odd corners of American culture. One of the questions in an exam administered to prospective citizens by the US Immigration and Naturalization service is: “The Civil War was fought over what important issue?” The right answer is either slavery or states’ rights. For Charles Dew growing up in the South of the 1940s and 1950s, there was no either/or. His ancestors on both sides fought for the Confederacy. His much-loved grandmother was a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In his dorm room at prep school in Virginia he proudly hung a Confederate flag. And he knew “that the South had seceded for one reason and one reason only: states’ rights…. Anyone who thought differently was either deranged or a Yankee.”

Later, however, as a distinguished historian of the antebellum South and the Confederacy, Dew was “stunned” to discover that protection of slavery from the perceived threat to its long-term survival posed by Lincoln’s election in 1860 was, in fact, the dominant theme in secessionist rhetoric. In Apostles of Disunion, which quotes and analyzes this rhetoric, Dew has produced an eye-opening study of the men appointed by seceding states as commissioners to visit other slave states—for example, Virginia and Kentucky—in order to persuade them also to leave the Union and join together to form the Confederacy. “I found this in many ways a difficult and painful book to write,” Dew acknowledges, but he nevertheless unflinchingly concludes that “to put it quite simply, slavery and race were absolutely critical elements in the coming of the war…. Defenders of the Lost Cause need only read the speeches and letters of the secession commissioners to learn what was really driving the Deep South to the brink of war in 1860–61.”

Those who do read the excerpts from speeches and letters quoted by Dew will find plenty of confirmation for this conclusion. “The conflict between slavery and non-slavery is a conflict for life and death,” a South Carolina commissioner told Virginians in February 1861. “The South cannot exist without African slavery.” The Mississippi convention’s “Declaration of Immediate Causes” of that state’s secession formed the basis for their commissioners’ message to other Southern states: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.” With Lincoln’s election,

there was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the union…. We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede….

Mississippi’s commissioner to Maryland insisted that “slavery was ordained by God and sanctioned by humanity.” If slave states remained in a Union ruled by Lincoln and his Republican cohorts, “the safety of the rights of the South will be entirely gone.”

And so on ad nauseam. The secession conventions and the commissioners grossly exaggerated the Republican threat to slavery in 1861. Lincoln had been elected on a platform of merely containing slavery’s future expansion. Republicans would not have a majority in Congress if the South stayed in the Union. But perhaps the commissioners deemed such exaggeration necessary to scare timid Southerners into support for disunion. That was surely true of their even more egregious distortion of the Republicans’ position on race. A Mississippi commissioner told Georgians that Republicans intended not only to abolish slavery but also to “substitute in its stead their new theory of the universal equality of the black and white races.” Unless white Southerners wanted “submission to negro equality…secession is inevitable.”

Georgia’s commissioner to Virginia dutifully assured his listeners that if Southern states stayed in the Union, “we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything.” An Alabamian born in Kentucky tried to persuade his native state to secede by portraying Lincoln’s election as “nothing less than an open declaration of war” by Yankee fanatics who intended to force the “sons and daughters” of the South to associate “with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality,” thus “consigning her [the South’s] citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollution and violation to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.”

So much for states’ rights as the engine of secession. In American history, states’ rights have been mostly a means, not an end, a tool rather than a principle—a truth demonstrated once again in the recent disputes about Florida’s ballots in the presidential election. Republicans supposedly in favor of states’ rights pressed their case in federal courts while Democrats looked to state courts. In antebellum America, Southerners controlled the national government most of the time until 1860 and they used that control to defend slavery from all kinds of threats and perceived threats. They overrode the rights of Northern states that passed personal liberty laws to protect black people from kidnapping by agents who claimed them as fugitive slaves. During forty-nine of the seventy-two years from 1789 to 1861 the presidents of the United States were Southerners—all of them slaveholders. The only presidents to be re-elected were slaveholders. Two thirds of the speakers of the House, chairmen of the House Ways and Means Committee, and presidents pro tem of the Senate were Southerners. At all times before 1861 a majority of Supreme Court justices were Southerners. This domination constituted what antislavery Republicans called the “Slave Power” and sometimes, more darkly, the “Slave Power Conspiracy.”

Historians have often dismissed such labels as another example of the “paranoid style” of American politics. But in The Slave Power, Leonard Richards demonstrates conclusively that there was a Slave Power. It had no need to function by conspiracy, however, for it could use the constitutional structure of government and the open operation of party politics to exert its domination.

One constitutional source of the South’s disproportionate political power was unintentional: the stipulation that each state would be represented by two senators. This provision had been adopted in order to win the support of small states—not slave states—for the Constitution. At the time of the Constitutional Convention the respective populations of the states lying south of the Mason-Dixon line and of those lying north of it were virtually equal in size, and many Southerners expected their section to grow faster than the North. As time passed, however, the opposite occurred. By 1850, when the number of free and slave states was equal at fifteen, the free states contained 60 percent of the total population and 70 percent of the voters, but sent only 50 percent of the senators to Congress. And Southern senators had more than a veto power; because they could count on several Northern allies, they could in effect deny a veto power to Northern senators on measures concerning slavery.

The South also had disproportionate strength in the House of Representatives. The “three-fifths compromise” adopted by the Constitutional Convention stipulated that three fifths of the slaves were to be counted as part of a state’s population for purposes of determining the number of seats each state would have in the House. This provision gave slave states an average of twenty more congressmen after each census than they would have had on the basis of the free population alone. The combined effect of these two constitutional provisions also gave slave states about thirty more electoral votes than their share of the voting population would have entitled them to have.

Even more than these constitutional provisions, the functioning of party politics created a Slave Power. The dominant political party most of the time from 1800 to 1860 was the Democratic Republican Party under the Virginia dynasty of Jefferson and Madison, which metamorphosed into the Democratic Party under the Tennessean Andrew Jackson and his successors. Southerners controlled this party and used their leverage to control Congress and the presidency. In 1828 and 1832 Jackson won 70 percent of the popular vote for president in the slave states and only 50 percent in the free states. In 1856 the Democrat James Buchanan carried only five of sixteen free states, but his victory in fourteen of the fifteen slave states assured his election—and Southern domination of his administration. As an example of how such leverage could translate into a Slave Power, six of the eight Supreme Court justices named by Jackson and his hand-picked successor were Southerners, including Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, author of the notorious Dred Scott decision and of other decisions that strengthened slavery.

As Richards makes clear, Southern politicians did not use this national power to buttress states’ rights; quite the contrary. In the 1830s Congress imposed a gag rule to stifle antislavery petitions from Northern states. The Post Office banned antislavery literature from the mail if it was sent to Southern states. In 1850 Southerners in Congress, plus a handful of Northern allies, enacted a Fugitive Slave Law that was the strongest manifestation of national power thus far in American history. In the name of protecting the rights of slave owners, it extended the long arm of federal law, enforced by marshals and the army, into Northern states to recover escaped slaves and return them to their owners.

Senator Jefferson Davis, who later insisted that the Confederacy fought for the principle of state sovereignty, voted with enthusiasm for the Fugitive Slave Law. When Northern state legislatures invoked states’ rights and individual liberties against this federal law, the Supreme Court with its majority of Southern justices reaffirmed the supremacy of national law to protect slavery (Ableman v. Booth, 1859). Many observers in the 1850s would have predicted that if a rebellion in the name of states’ rights were to occur, it would be the North that would rebel.

The presidential election of 1860 changed the equation. Without a single electoral vote from the South, Lincoln won the presidency on a platform of containing the future expansion of slavery. Southerners saw the consequences that would likely follow. The Union now consisted of eighteen free states and fifteen slave states. Northern Republicans would soon control Congress, if not after this election then surely after the next. Loss of the Supreme Court would follow. Gone or going was the South’s national power to protect slavery; now was the time to invoke state sovereignty to leave the Union. With Lincoln’s election, wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr., the son and grandson of the only truly “Northern” presidents the country had known, “the great revolution has actually taken place…. The country has once and for all thrown off the domination of the Slaveholders.”12 Precisely. Slaveholders came to the same conclusion. So did other Southern whites. “If you are tame enough to submit,” the Baptist clergyman James Furman told South Carolinians, “Abolition preachers will be at hand to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands.”13

They did not submit; they seceded. As another South Carolinian explained, “We are contending for all that we hold dear—our Property—our Institutions—our Honor…. A stand must be made for African slavery or it is forever lost.”14 One slave state after another followed. If it came to war, predicted a secessionist in December 1860, the Southern states “will have among themselves slavery, a bond stronger than any which holds the North together.”15 That bond did help to hold the Confederacy together through four grueling years of suf-fering, destruction, and death. In 1863 a cavalry lieutenant from Mississippi reaffirmed his belief that “this country without slave labor would be wholly worthless…. We can only live & exist by that species of labor: and hence I am willing to continue the fight to the last.”16

As Gary Gallagher notes in his introduction to The Myth of the Lost Cause, “White Southerners emerged from the Civil War thoroughly beaten but largely unrepentant.” Some proponents of the Lost Cause remained candid about the racial ideology that sustained the Confederacy. The unrepentant Edward Pollard, wartime editor of the Richmond Examiner, wrote the first history of the Confederacy, with the appropriate title The Lost Cause. The war had ended slavery, Pollard acknowledged, but it “did not decide negro equality…. This new cause—or rather the true question of the war revived—is the supremacy of the white race.”17 In a speech to Confederate veterans in 1890, a former captain in the 7th Georgia Volunteer Infantry echoed Pollard: “We fought for the supremacy of the white race in America.”

Such candor was exceptional in commemorations of the Lost Cause. More popular was Jefferson Davis’s postwar assertion that slavery was “in no wise the cause of the conflict, but only an incident.” In considering this “incident,” it would be well to keep in mind Henry David Thoreau’s observation that circumstantial evidence is sometimes conclusive—for example, when you find a “trout in the milk.” All of the Confederate states were slave states and all of the free states remained in the Union. That is a rather large trout.

3. Augusta Daily Constitutionalist, March 30, 1861. ↩

4. Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, two volumes (Da Capo, 1990), Vol. 1, pp. vii, 67, 156. ↩

5. Alexander H. Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, two volumes (National Publishing Co., 1868–1870), Vol. 1, p. 10. ↩

6. The Washington Post, January 16, 2001, p. A21. ↩

7. Frank Lawrence Owsley, “The Irrepressible Conflict,” in I’ll Take My Stand, by Twelve Southerners (Harper and Brothers, 1930), pp. 61–91, quotation from p. 73. ↩

8. Avery Craven, “Coming of the War Between the States: An Interpretation,” in An Historian and the Civil War(University of Chicago Press, 1964; essay first published in 1936), pp. 28–29. ↩

9 Avery Craven, The Coming of the Civil War (University of Chicago Press, 1942), p. 93. ↩

10. Newsweek, October 8, 1990, pp. 62–63. ↩

11. W. Keith Beason, letter in North & South, Vol. 4 (March 2001), p. 6. ↩

12. Quoted in Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War(Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 223. ↩

13. Quoted in Steven A. Channing, Crisis of Fear: Secession in South Carolina (Simon and Schuster, 1970), p. 287. ↩

14. William Grimball to Elizabeth Grimball, November 20, 1860, John Berkley Grimball Papers, Perkins Library, Duke University. ↩

15. Berkley Grimball to Elizabeth Grimball, December 8, 1860, John Berkley Grimball Papers. ↩

16. William Nugent to Eleanor Nugent, September 7, 1863, in My Dear Nellie: The Civil War Letters of William L. Nugent to Eleanor Smith Nugent, edited by William M. Cash and Lucy Somerville Howarth (University Press of Mississippi, 1977), p. 132. ↩

17. Edward A. Pollard, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates (E.B. Treat, 1866), p. 752; Pollard, The Lost Cause Regained (G.W. Carleton, 1868), p. 154. ↩

August 9, 2017

The untold stories

of women in the

1967 Detroit rebellion

and its aftermath

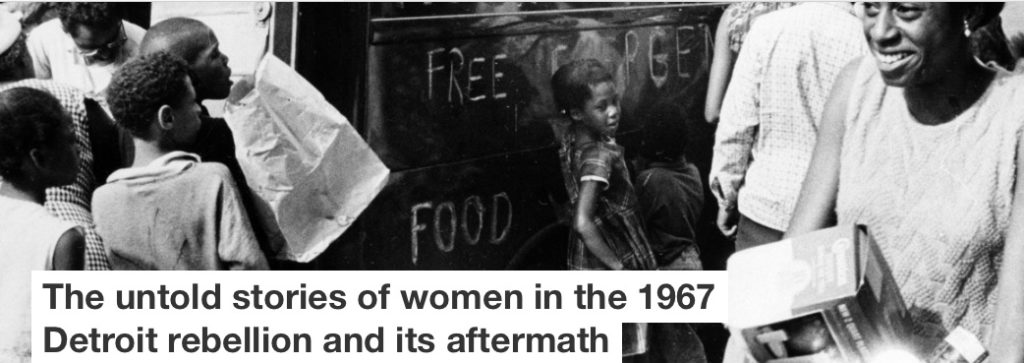

People gather around a truck to get food on Detroit’s east side in July 1967. The food was brought to the riot-stricken area by the Crisis Council, one of the many organizations aiding residents. AP Photo

The movie “Detroit,” which tells the story of the 1967 Detroit rebellion, has received mixed reviews since its release. Some praised the film for tackling a complex, little-known story, while others criticized it for its representation of the the city, the historical events and actors involved. In many respects, the film is limited, with the voices and perspectives of women and girls lacking.

I moved to Michigan in the fall of 2013 to begin teaching theater for social change and performance studies at Michigan State University. As a Chicago native, I knew little about the history of Michigan and Detroit.

I began researching the 1967 Detroit rebellion to answer my own questions about what had happened. When I began to review the wealth of materials found in oral history collections and newspaper archives, I was struck by the lack of any sort of perspectives from the women and girls who witnessed and participated in the uprising.

In photo after photo, women and girls appear alongside men and boys. Of the over 7,000 people arrested from July 23 to July 28, 1967, between 10 and 12 percent were women or girls. (The youngest was 10 years old.) Forty-three people were killed, including two white women and one little girl, Tanya Lynn Blanding, shot and killed by the National Guardsmen who opened fire on her building.

Who were these women and these girls? What were they doing on the street? What roles and responsibilities did they take during and after the military occupation, and later, when industry and investments fled the city?

Those questions inspired me to develop a new play called “AFTER/LIFE,” which focuses on the experiences of women and girls in Detroit before, during and after the rebellion.

Rather than beginning that story with the raid on the unlicensed after-hours club on July 23, 1967 – as the film does – I decided to focus on the activism that emerged following the police murder of Cynthia Scott in Detroit four years earlier. Long before 1967, the issue of police brutality was at the forefront of Detroiters’ minds, with women and girls going on to play prominent and important roles in the rebellion and its aftermath.

The history of police brutality in Detroit is long and complex, but at no time have men or boys been the exclusive targets of their violence. In the early morning hours of July 5, 1963, police stopped Cynthia Scott and a male companion as they walked down John R Street near Edmond Place.

Scott was a young, African-American woman with a history of engaging in sex work to survive. According to several witnesses who spoke to the Detroit Free Press, despite Scott’s repeated assertions that she was with her boyfriend and that they had the right to walk down the street, Detroit police moved to arrest Scott on suspicion of prostitution. She broke away and officer Theodore Spicher shot her three times. She fell face down on the pavement dead.

Witnesses contested Spicher’s official statement that she had pulled a knife on him before he shot her. Local activists took up the case as a rallying cry. The Illustrated News, a grassroots circular published by civil rights leaders, carried a two-page story accompanied by detailed picturesof community members picketing the police headquarters.

Segregation in 1967 Detroit meant there were few opportunities for blacks to live, work or socialize freely. Racist public policies called for the overpolicing and underprotection of Detroit’s black communities. Underground bars called “blind pigs” filled a vital need for safe places for adults to relax, mingle and exchange ideas.

In the scorching hot, early morning hours of Sunday, July 23, 1967, Detroit police raided the “blind pig” run by William Walter “Bill” Scott II at 9125 12th Street. As the police slowly loaded the 80-odd partygoers into paddy wagons, neighbors gathered on the street to watch. A rumor circulated through the crowd that the police had manhandled at least one woman. For Scott’s 19-year-old son, William Walter Scott III, a lifetime of frustration over police misconduct fueled the first bottle he threw. The chaos spilled into the street, the police pulled back and looters broke into local stores. The disturbance would escalate as the crowds – and the response by law enforcement – would turn increasingly violent and deadly over the next several days.

In 1967, women worked in many of the businesses that were impacted by shoplifting and arson. Some of the women I spoke with – who were girls at the time – recalled that older women, including their aunts and mothers, discouraged shoplifters from taking items from the grocery stores and dry cleaners where they worked on 12th Street.

I learned from interview subjects that in other instances – recognizing that the food and goods would rot or be destroyed – women encouraged people to take what they could carry for themselves and their families. Many understood that 12th Street, one of the most vibrant corridors for black businesses, was being destroyed, and that it would take some time for these much-needed jobs and services to return, if they ever would.

Female prisoners arrested during the rioting in Detroit board a bus at Wayne County Jail, watched by National Guardsmen. AP Photo

Despite the fires and rampaging police and National Guardsmen, black women took to the streets and put their lives on the line. For some, this meant taking food and other items they needed for friends and family; for others it meant personally ensuring family members made it out alive.

During performances of “AFTER/LIFE,” patrons were asked to share their memories. One man recalled that his mother piled her children into a car to evacuate them out of the city. Another woman told us that her mother faced down a National Guardsmen’s rifle and bayonet to get her children home. Teaching their children to load weapons, to hit the floor and duck for cover to avoid getting shot by the police, and to be forever wary of men in uniform – all of these things became a necessary part of mothering during the rebellion.

As police and National Guardsmen escalated their attacks on black Detroiters and local businesses came under fire, black women also worked to deescalate the violence. Oral histories and archival materials reveal that they carried sandwiches and lemonade to guardsmen and police who were deployed without provisions in their communities. Most importantly, women activated longstanding community organizing networks to provide food, water and shelter to those Detroiters who had been displaced by the violence. Women in positions of influence, from Grace Episcopal and New Bethel Baptist churches to the Temple Beth El synagogue, rallied together.

Radio host Martha Jean ‘The Queen’ Steinberg gave her listeners regular updates, working to defuse the chaos. Voices of East Anglia

This vital, “behind-the-scenes” work would have been impossible without a concerted effort on the airwaves. Martha Jean “The Queen” Steinberg, a prominent black radio host, convinced her station managers at WCLB-AM1400 to interrupt their regular programming and allow her to go on air. For the next 48 hours, she would urge calm while giving her majority-black listeners the latest updates, including how local, state and national leaders were responding to the crisis and where they might get help.

Some of the hardest tasks fell to women such as Margaret Gill, Rebecca Pollard and Viola Temple, the mothers of the teenage boys killed by police at the Algiers Hotel. Along with June Blanding, whose four-year-old daughter, Tanya, was murdered by National Guardsmen while she slept, these women organized immediate aid for the victims and led the longer-term charge for justice.

Women also played key roles in a “People’s Tribunal,” which was organized to hold the police and National Guard accountable. On August 30, 1967 at the Central United Church of Christ (later the Shrine of the Black Madonna), Rosa Parks, a veteran of civil rights organizing, sat as the lead juror in the mock trial that drew hundreds of spectators and ultimately found the police guilty of murder. While the tribunal would have no impact on the formal, criminal proceedings, it provided a necessary and important space for the community to tell the truth, express its anger and frustration, and receive a measure of social justice.

Fifty years later, Detroiters are engaged in a large-scale act of commemorating the 1967 Rebellion. Art and history museum exhibits, panel discussions, book releases and performances have been staged across the city by grassroots organizations and cultural institutions. Men continue to figure prominently in the coverage.

Curators at the Detroit Historical Museum acknowledged as much when they posted a sign in their exhibit that asked patrons, “What’s missing?”

Their answer: the perspectives of people of color and women. As long as our stories about the 1967 Detroit Rebellion overlook the knowledge and experiences of women and girls, they will continue to circulate half-truths and false representations of the city, the causes of the uprising and the world Detroiters inhabit today.

+++++++++++

is Assistant Professor, Theatre and Performance Studies, Residential College in the Arts and Humanities, Michigan State University

May 10, 2017

This interview is published in dialogue with Samuel R. Delany’s short work of experimental memoir, “Ash Wednesday.”

Junot Díaz: Chip, “Ash Wednesday” is a wonderful essay. Jonathan Lethem once described you as a confessional “genius” and yet even by the standards of your extraordinary autobiographical work this essay stands out—it is so singularly guileless and free of judgment that after reading it I wanted to approach the world in a similar way. You mentioned before our conversation that you wished that I’d seen Charles Lum’s documentary Secret Santa Sex Party (2016). What specifically about that documentary were you struck with, given your own direct experience with the party in question? Which came first for you, the documentary or the party?

Samuel Delany: Lum has made two documentaries, actually. More accurately, he’s made two versions of one documentary: Secret Santa Sex Party is fifteen minutes and explicit. It’s very good. Why? Because it actually shows what these guys do at the party that I attended. It was the same men for the most part whom I went and played around with. Then there’s a seventy-minute version, Sex and the Silver Gays (2016), which contains all of Secret Santa Sex Party as well as a number of interviews with the guys. That I haven’t seen. But I want to. I suspect everyone should, if only to continue the normalization process.

Radicalism begins in the body. Being a sex radical means being willing to speak about it in places you ordinarily wouldn’t.

I went to the party first. Then on April 16, after having written the early draft of my essay, I saw the film in a showing of gay films at the Prince Theater, here in Philadelphia—Lum came down and took me and Dennis to dinner, and I went to the screening. The documentary was made three months before I went to the party. But that just made it seem I was involved in the same process. And I had had sex with maybe half a dozen of the guys I subsequently saw on the screen. That was certainly a first for me. (It was playing with an unbelievably clichéd film called Grinder (2016)—the only good thing you can say about it is that it had nothing to do with the gay hookup app Grindr. Would that it had!) Sitting in a movie theater and looking at the screen and thinking, yes, I’ve actually had sex with him, as you are watching him have sex with someone else (or pretend to), has got to be an experience pretty limited to the community of movie actors—perhaps the community of porn film actors. But when those communities shift radically, it means something—and not just approaching mortality.

Not all explicit sex is pornographic. It can be educational, and I expect that a room full of forty- to eighty-year-olds having sex and discussing their lives would be just that: educational. That’s certainly how I found it, both my single encounter with eighty-five-year-old Eric, my various encounters with older guys cruising on trains when I was in my forties, and these guys in the DoubleTree. They aren’t breaking any laws. They’re enjoying themselves and caring for their own community. And they’re talking honestly and intelligently.

JD: So will you be going back?

SD: It would be far easier if a similar institution were operating here in Philadelphia, even in the Gayborhood in which I live, and I could walk up the street and visit it, instead of having to get on a bus and ride two hours to New York, while I’m trying to get it all into one trip including my visit to my old fuck buddy Maison and his husband Fred, which was a different kind of experience, but finally the more satisfying one, I believe, as I hope I suggested in the essay.

JD: The sex party you describe is a kind of secret community in the middle of midtown Manhattan. On the other hand, everything within it is so transparent, so true, for lack of a better word. Is this a heterotopia?

SD: Heterotopia just means a “different place” or a place where different things can happen. It’s also a medical term, for moving an organ or even tissue from one part of the body to the other. Thus a skin graft or even a surgical sex reassignment can be called a heterotopia. The point, of course, is that it’s not secret. It’s not illegal. Bob does what he does out in the open, and he should. He approaches older men he thinks are good-looking on the street, just the way he did me, and is often successful. Bob’s right to do it—it is vouchsafed by law and he doesn’t annoy anyone so much that he gets punched for it. I talk about the false dichotomy between private and public in the long letter in The Mad Man (1994). There really are subcultures, and they are intra- as well as intercultural, since we all share so many chromosomes—not just human beings, but chimpanzees, gorillas, oak trees, algae. The range of cultural communication has turned around the wheels of social change far faster than ever before.

Not all explicit sex is pornographic. It can be educational. Eighty-year-olds having sex and discussing their lives is just that: educational.

There’s an irony in the term heterotopia that sometimes escapes. I used to sing with the husband of a high school friend, Ellen Kravet—his name was Nat Goldberg. Once he had a motorcycle accident and scraped all the skin off his palm, and had to have a skin graft from another part of his body. One day in the East Village near Gem Spa he showed me his hand—where he’d had a skin graft from his thigh or back. He had body hair all over the palm of his hand. That too is a heterotopia. We made the obligatory jokes about werewolves.

JD: People have called you a sex radical. What do you suppose they mean? What does it mean to you? Does it come with any political commitments?

SD: Intellectual radicals, rather than actual radicals, are people who say things where they are not usually said. And, yes, all true radicalism has to begin in the body—so being a sex radical means you have to be ready to act radically and be willing to speak about it in places you ordinarily wouldn’t—such as an interview about an activity you might otherwise confine to a journal. That’s how I started—and the world got started around me, as it were, when my mother found my secret writings, took them to my therapist, and they ended up in an article: Kenneth Clarke, who was the head of the Northside Center where I was going for child therapy, quoted them in an article in Harper’s and again in his book, Prejudice and Your Child (1955), and I found myself published because of it. My first professional sale, as it were. I got a lot of attention for it, too. It is the source of most of my “radicalism.”

JD: You once said that “there were far more opportunities for sex among men before Stonewall than since.” Let’s expand that a little to the larger question of what generational differences among gay men strike you as most significant?

SD: You have to remember there’s always what’s said and then there’s what happens. And there’s always a discrepancy between them. Human beings are definitely tribal, as much as wolves and apes are. And the fact that only one sex carries the young to term immediately starts the separation into cultures. Do you want it in public, in private, or in a special space that’s socially marked out? Do you want pictures or reproductions (and if so, what sort) of those public or private or socially marked out space? That’s finally what my book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999) was about.

JD: Alright, crap question.

SD: I didn’t think it was a crap question. Rather it’s about how you want your sex mediated—or what you’re used to. Do you want it in a group, or in private, in a group who’re used to it that way; do you want it in private, in public, in a group mediated by hand and machine, or hand and genitals, or genitals and genitals, mouth, anus; what do you want the bodies, the genitals, to look like, feel like, reflect in terms of ethnicity and specificity.

What surprises me is how much I don’t miss the dead. But I feel diminished by the death of friends. It’s like losing a part of your library—a part of your brain.

JD: How do you see “Ash Wednesday” in the context of your other autobiographical work? What surprised you as you composed it?

Samuel Delany: Very little—other than the clumsiness I fell into while writing it, which—with reading after rereading—I had to strike out. (I still write that poorly? That’s the message I always hear from the critical part of my brain when I read over what I’ve put down.) I shouldn’t call that a surprise—on the contrary. But the mistakes are what flood over me every time I reread the last phrase, clause, sentence I’ve typed.

JD: Thou art hard, my friend. When I read “Ash Wednesday” what flooded over me is your excellence. The title is taken from the Catholic holiday that reminds believers of their mortality and demands humility and obligation. Is there any similar kind of devotion in the communities you describe? Or is this speaking to the fact that when one is older mortality stops being just a concept?

SD: As I’ve aged, I’ve seen people die: a brilliant young man, Robert Morales, whom I met when he was seventeen and I was thirty-two, was, for a number of years, slated to be my literary executor—of course he was going to outlive me. His sister Arlene had had leukemia, and he nursed her through her death at twenty-one. Later, his father came down with colon cancer, and a couple of times I met them in the halls of the AMC-25 Empire Theater on the New Forty-Second Street where you and I used to go to watch bad science fiction films—it was his father we were all expecting to eventually succumb. Only one day, our mutual friend, the artist Mia Wolfe, phoned me to say, “Chip, Robert died this morning!” Robert too had colon cancer—but didn’t know it—and what he’d thought was a three-day bout of indigestion had suddenly ruptured his lower intestine. Sitting on the commode he’d collapsed, one cheek flattened against the sink, and died. His father had called in to see if he wanted an orange juice and found him dead. So I lost a good friend, a wonderful editor and advisor, and had to find a new literary executor.

Robert’s parents had already lost one child to leukemia and I don’t know what losing another was like. His friends flew in to the funeral from all over the country. Robert was Puerto Rican, and very much a black Puerto Rican: he was perpetually late and perpetually people forgave him because he had so much else to offer. I don’t know if you ever met him, but he was one of the best literary advisors you could have, and he did innumerable small editing jobs for me—such as getting my Paris Review essay into shape, when Rachel returned her final version to me. And he was a good, good friend.

JD: I knew Robert’s work well but never got a chance to meet him. His death was a terrible loss.

SD: Then there was the time I woke up and learned that my closest friend in the SF community, David Hartwell, had fallen when moving a bookshelf in his home and had suffered a brain bleed; he was already brain dead, and was pronounced officially dead the next day. What surprises me is how much I don’t miss the dead. But I feel regularly diminished by the death of good friends. It’s like losing a part of your library—a part of your own brain. It’s as rupturing and as hurtful—but is not sad. They had incredible amounts of knowledge and skill with which they were wonderfully generous. Both were great editors. Both were no slouches as writers, either. Robert wrote the classic Marvel series, Truth (2003), about the black Captain America—the one that Kyle Baker drew—and it’s still a wonderful comic. I worked for David at least twice, once at Cosmos Magazine and once as his assistant at Arbor House. Not a lot of people knew David had a PhD in late medieval literature from Columbia University. I remember him working on it; his thesis was an edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. And he was as supportive an editor to Marilyn Hacker, my ex-wife, as he was to me, publishing her novel in sonnets (modeled on George Meredith’s Modern Love, which we’d both read and marveled at), which I feel proud to have suggested a title for, from Robert Graves: Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons (1986).

Losing good friends at my age is like losing your own resources. “Any man’s death diminishes me. . . .” John Donne’s line has a much realer meaning as you yourself age.

The technology I use is often beautiful. But more and more it bewilders me. When I can’t use it and I need to that scares me, and I think scares others my age.

My father’s death in October 1960, when I was eighteen, freed me, I think. Though it perhaps robbed me and my sister of a chance for a certain later coming to terms with him personally. It had not been a happy relationship. I was lucky that the naturalness and community nature of death were parts of my life quite early. My father had been a funeral director in Harlem, where I grew up. Before writing the essay we’re talking about, I reread T. S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday” which, I suppose, is very much a poem of release and the contemplation of loss. It didn’t give me much—but that’s how I’ve felt about Eliot’s more devotional efforts for decades. That’s a literary fact that has to be accepted.

Mortality is, of course, the defining human concept. We are mortals. We are told that from the day we can speak, and we come to learn more and more what mortality means and doesn’t mean, according to tribal traditions. We are creatures who will die and know it. Such things change over time—but when they change within a lifetime, the earliest things are still there. And they include all the ignorance one was brought up on. Ash Wednesday is not an important Episcopalian holiday in the same way as it is in the Catholic Church. It was always what other people did. Even in the essay, it serves as a sign of what others do or do not do.

When I was twenty, I simply didn’t know that there could be organized sex parties among older men or sixty, seventy, or eighty. I’ve always liked older men. But I was very surprised when I realized I could find older men who could give me a good time. In the first weeks I was in the apartment I still live in, here in Philadelphia, I was at the gay bookstore Giovanni’s Room and met a young fellow in his late twenties who liked older guys and wanted to go home with me and have sex in the shower. The community sketched in the essay is devoted to its older men. And people such as Bob Woof, who organizes the sex parties, really are devoted in that way.

In “Ash Wednesday” I write about Lige, whom I met when he was a rambunctious five-year-old at a Memorial Day barbecue. A decade later, I remember him as a sensitive sixteen-year-old living in a trailer park. His cat had died that afternoon, and he was too depressed to go out for pizza with Maison and me, so we went without him; at nineteen he had a child and a wife two years his senior who’d brought two earlier children to the marriage; they were still in the trailer park, and seven years later, he was dead from a incorrectly administered dose of Plavex for the heart condition he’d developed. He never reached thirty, and that’s the aspect of mortality that bothers me. I think of all the black kids, the disabled kids, the Asian kids who are luckier that he was, simply because he was poor and white and had had appalling medical care all his life and no education, and even worse luck in his acquaintances and family.

Dennis is pretty devoted to me—that I know.

JD: To switch gears a little: back when you were writing science fiction regularly you were never a hardware person, though some of the hardware you did devise—I’m thinking of the Scorpions in Dhalgren—is simply marvelous. But in “Ash Wednesday” there is an awareness of technology that I’ve not seen in your previous work. What’s going on?

I think the people you are comfortable seeing in person are finally the ones who offer you the most help.

SD: Technology is a problem. It’s a problem for me. The speed with which it has changed—and is still changing—is dazzling. When I got my first Apple, I signed up for a hundred dollars worth of lessons—and never took them. That remains one of the stupidest things I ever did. If I had, possibly the last third of my career would have been different. In the same way I never learned to touch type with two hands—that’s completely stymied my writing and added the problem, on top of my dyslexia, of clumsy typing as soon as I try to go faster than twenty words a minute. And I’m the guy who built a computer in his sophomore year of high school and got an honorable mention for it in the annual science fair. But I’ve never learned the simplest basics of how to use my computer to do more than type and send simple emails. I can do math on my iPhone but not on my computer, because I have a calculator app. I’m only learning now how to maneuver with the address bar. There are things you can do with the yellow minimize button that I’d never thought about before.

It really does take me three to five times as long to learn anything as it once did. There are things that Dennis, my partner, and Bill, my assistant, find easier to do for me than to let me do. But I have to badger Bill again and again to spend time drilling me on what I need to know—even at seventy-five. The technology I use is often beautiful. But more and more it bewilders me—even the primitive voice technology we have with something like Siri, which at this point could certainly not pass a Turing test, is something I can only use to set a timer to cook my morning oatmeal. When I can’t use it and I need to—which is more and more pretty much everyday—that scares me, and I think scares others my age. My landlord, who is a year my senior, doesn’t even do emails! My bank just announced it’s going to go to voice recognition technology. Is this going to replace passwords or be on top of them? My voice is not the same as it was ten years ago; I know that because I’m very close to it. It’s part of my body—as is my ability to type, which is the interface with so much of our phone and laptop and computer technology.

JD: You are an inveterate Facebook user, though.

SD: That’s right; it presents an illusion of managed relationships, extended and virtual neighborhoods, as we find ourselves enmeshed in more and more of them, with our taxes, our health insurance, our banking, our education all mediated through keyboards, monitors, and microphones, which take over the body more and more. Think of the immensity of the porn industry, as it disperses in time and space.

Illiteracies are as fascinating as literacies—and I think that’s important. And I’ve always tried to write about them too. As far as technology is concerned, I feel far closer to an illiterate than a literate member of the computer age. Others on Facebook have told me the same thing. My friend Maison doesn’t read or write; he doesn’t type. Fred can use a computer, but they rarely do. They have two, I believe. They have a younger friend who comes by and helps them with banking and insurance. And also to see what I’m doing in Facebook.

JD: You go into this trip with some anxieties related to aging: about worsening ADD, and about the worry that the world is passing you by. Did the trip help relieve either of these? What does writing about them do for you?

SD: Well, it’s a way to help me think about them clearly, and a way to remember them. Napoleon rather famously used to write himself notes, then tear them up. Just the writing itself was an aid to memory. Well, it is, but if you are a writer, often you have to do even more than that.

For every book I’ve written there were thirty that I wanted to write, started to write—then petered out or gave up.

I don’t feel the world is passing me by as long as I can relate to real people in person. Take you and me—we started in the same city, New York, a bus ride apart. We could get together and go off for wonderful cooked-at-your-table Korean food in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Then, suddenly, you and Marjorie are four states to the north, in Cambridge, and, with a couple more orbits around the sun, Dennis and I are in Pennsylvania, first in Wynnewood, then back in Philadelphia. And with each further separation, the possibility of communication is attenuated. But no single trip is going to do it for anyone. I think the people you are comfortable seeing in person are finally the ones who offer you the most help.

JD: You are, in my opinion, one of the greatest living American writers. Your books fill up two complete shelves on my wall and that’s not including the volumes that have been produced about your work. Do you feel as though you have written what you wished to write? Did anything slip away from you? What’s next for you?

SD: For every book I’ve written there were thirty that I wanted to write, started to write, got halfway or three-quarters of the way through or maybe only four or five pages through—then petered out or gave up. I have always had to do lots of rewriting. And I’ve been told some of it’s good, and some of it’s bad. Two of those starts got pretty far along—and I wanted to see if I could salvage something from them. Right now it feels as if I can’t go draft any more complete novels. But the final part of your question slid across two others to get there.

—First, have you written what you wished to write?

Does anyone? What you wish to write changes, day to day, hour to hour sometimes, and is braided with all the things you have to do to be able to write at all—from self-care to physical and technical skills. How much control do you have over your own focus and energy? From the time I was a child, I wanted to weave my works into larger works—and they were always coming apart and falling to pieces.

—Second, did anything slip away from you?

There are hours when it seems as if everything did! Both fiction and nonfiction! The unfairness of finding oneself a writer who can’t hold onto the spelling of words! (The dyslexia.) To have a nervous system that, as you try to touch type your way through a sentence, is as likely to hit a letter with the third finger of the right hand as with the left, or is as likely to type an l as a w. In my journals I have perhaps four and a half different kinds of handwriting, and am likely to slip from one to another—now using a version of print, now a version of cursive, or something in between.

Modesty and moderation are what produce art, I think.

I’ve gotten up ten times in the midst of this paragraph to see what Dennis is doing in the other room, but not disturb him at it, and that’s a habit established over a year back in this flat, which is very similar to something that used to happen in the large apartment in New York we had, but was all but impossible to do in the back rooms off the kitchen when we lived in Wynnewood, with the kitchen between the library and my office; and when we move again, it will be different still. These patterns have to contain sex and food and food preparation, and conversation and the hours when my assistant comes. That anything gets done, much less something that seems to a few people worth reading, seems miraculous.

What’s next for you? That was the final part of your last question.

Hey, I hope I get to the last sentence of this interview more or less able to write another, and get through the various tasks the rest of the day presents me, some of which will concern writing and some of which will not.

I don’t know if you saw a credo of mine I restated recently on Facebook; I throw it in here: The violation of reproductive rights is not the only problem women have. First, not all women reproduce. Second, not all women reproduce their entire lives long. Third, the discrimination that women face starts when they are born and continues through till they are dead—and, in terms of historical presentation of their achievements and struggles or just their ordinary lives, often beyond. Fourth, the patterns of prejudice and discrimination against women are the model, adjusted, for all other forms: racial, religious, and all the others. The infantilizing, the devaluation of experience, the stigmatizing, the economic punishment is all learned with women and applied to the others. Although the group I tend to concentrate on and have for the last thirty-five-odd years is gay men, because it is the one I belong to, I have been aware since my teens that prejudice against women is the main source of our political dilemma. Fix that, in terms of transgender women, gay women, black women, Asian women, poor women, and cisgender white women, and you go a long way toward fixing the whole machine. And fixing any male group’s problem (or individual’s) has to be done with an awareness of the whole.

In the eighties, to get a passport all you needed to do was show up at the office with someone who would swear to knowing you for two years.

My partner Dennis’s problem right now—because he was homeless for six years—is getting a picture ID, but I spent a month last November standing in lines of the homeless several hundreds long, and learned that there were more homeless women with his problem than men (and more black women than white), which, bluntly, is one reason the problem is as hard to fix for him as it is.

JD: Too many people in this country in similar plights. Far too many.

SD: Yes, and in Canada as well. We had a talented young journalist, Megan Marrelli, come see us about a month ago. She had already done an article on a friend of mine named Danny McLaughlan, whom I’ve known thirty years, since he was a working stiff (an old slang term for a hustler) in New York. Now in his fifties, he’s working in Toronto, but has never had any ID. The article mentions Dennis and me in passing. It’s a good article, too. After she finished it, she came to Philly to do an audio piece just on Dennis and me. I tried to put her in touch with our lawyer, but that didn’t work out. But the point is, Dan and Dennis, a country apart, are both in the same position as far as ID is concerned. Neither one of them has it. Neither one seems to be able to get it. Apparently you can’t get a picture ID or get into any of the loops that will get you one without already having one from somewhere.

In the mid-eighties, to get someone a passport who didn’t have one, all you needed to do was show up at the passport office, which in New York City used to be on the second floor of the Rockefeller Center, with someone who had known you for two years or more and swear in front of the agent and sign the form. I know, because that’s how I got one for my first long-term lover, Frank Romeo, who had also had periods of homelessness, less severe than Dennis’s, but which had still cost him his ID. But by the time I got together with Dennis, it was being handled so differently that it was practically impossible, and once 9/11 occurred, it became more difficult still.

From one afternoon standing in a line of a hundred homeless men and women, seeking help, I saw, as I stood there trying to help Dennis, that the largest group that has this problem is clearly black homeless women, gay and transgender, followed by black gay men. Dennis, the one white guy, was exhausted with fighting and so had sent his black gay partner to stand in his place!

I hope Megan’s next piece reflects this reality that the problem is mostly faced by homeless black women. And it is all but insoluble precisely because it is largely a homeless gay woman’s problem. The rest only share that difficulty. It’s not so different from the avant-propos of Les Misérables:

So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine, with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.

19 August 2017

As we wrap up the annual July Month of Grilling for 2017, I thought I’d share one of my favorite salmon recipes with you. While we had a lot of fresh-from-the-ocean fish and seafood on the islands when I was growing up, for some reason our salmon always came from a can (say ‘tin’) for some reason. Especially around Easter-time when mom would prepare a host of ground provisions, topped with stewed canned salmon. While I still use the canned stuff, I do enjoy the fresh (as can be expected since I don’t live near the ocean)salmon we get here Ontario.. when I can afford such!

You’ll Need…

2 large salmon steaks

1/2 cup crushed pineapple

1/4 cup orange juice

2 tablespoon light soy sauce

1 birds’s eye pepper (diced fine)

1 scallion (chopped)

1 tablespoon honey

1 clove garlic (crushed)

1/2 lemon (juice)

1 teaspoon grated ginger

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

1/4 teaspoon sea salt

IMPORTANT! If doing this recipe Gluten Free, please go though the list of ingredients to ensure they meet with your specific gluten free dietary needs. Especially the Soy Sauce.. please substitute for a gluten free version.

Basically all you have to do is place all the ingredients into a bowl (except the fish) and give it a good whisk to combine the flavors. As I mentioned in the video below, I forgot to include the diced pineapple in this version of the recipe, but I strongly recommend you include it.

Then pour 1/2 of the marinade over the cleaned/dry salmon steaks and marinate for ONLY 5 minutes. IMPORTANT – any longer and lemon juice and pineapple the marinade will start breaking down the salmon.

Then it’s just a matter of grilling them over a coal fire (propane gill works fine too) until they are cooked to your liking. I grilled indirectly for the first 5-7 minutes, flipping and basting with the reserved marinade. Then I had them over the direct heat for 2-3 minutes.

Do keep in mind that the sugars in the marinade will cause the fish to char very easily (I like a bit of that char though) and the cooking time will vary on how thick your salmon steaks are, the temp of your fire and how ‘cooked’ you like your fish. I’d also recommend saving a tablespoon of the marinade to drizzle over the cooked salmon after you remove them off the grill (but while still warm).

Are you following us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram yet? Join in on the fun today!

>via: http://caribbeanpot.com/the-ultimate-grilled-salmon-recipe/

The Ake Arts and Book Festival is calling for submissions to the 2017 edition of our annual journal, Ake Review. This 5th Edition is themed This F-Word and will focus on the challenges, journeys and triumphs of African women, while exploring a range of feminist perspectives.

Ake Review welcomes entries in all literary and artistic genres including: fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, reviews, photography, film, music, sound art, performance art, and visual art. Entries can be submitted in written form, as podcasts, or as videos. Pieces that explore multi-genre, inter-disciplinary, and multimedia formats are encouraged.

>via: https://africainwords.com/2017/08/13/call-for-submissions-ake-review-2017-deadline-31-august-2017/

Open: First day of each month.

The Bare Life Review is a biannual literary journal that gives publishing opportunity exclusively to immigrant and refugee authors.

They are currently accepting unsolicited manuscripts in fiction, non-fiction, and poetryand are offering a rate of $1000 for accepted prose pieces, and $400 for accepted poems.

Since the journal is exclusively dedicated to immigrant and refugee authors, the journals editors will only accept work from “writers living abroad who currently hold a refugee status” and “foreign-born writers living in the United States.” You can read more about the eligibility guidelines HERE.

The editors are looking

Fiction should be no more than 8000 words, nonfiction no more than 6000, and no more than 3 poems.

Submission period: August 1–December 31

This is an opportunity to take part in a one-of-a-kind creative project. We encourage anyone in our community who is eligible to send in their work.

To learn more about The Bare Life Review, contact the editors, and get more submission information, click HERE.

>via: http://brittlepaper.com/2017/08/opportunity-african-writers-bare-life-review/