JUNE 3, 2014

AN S.O.S. IN A SAKS BAG

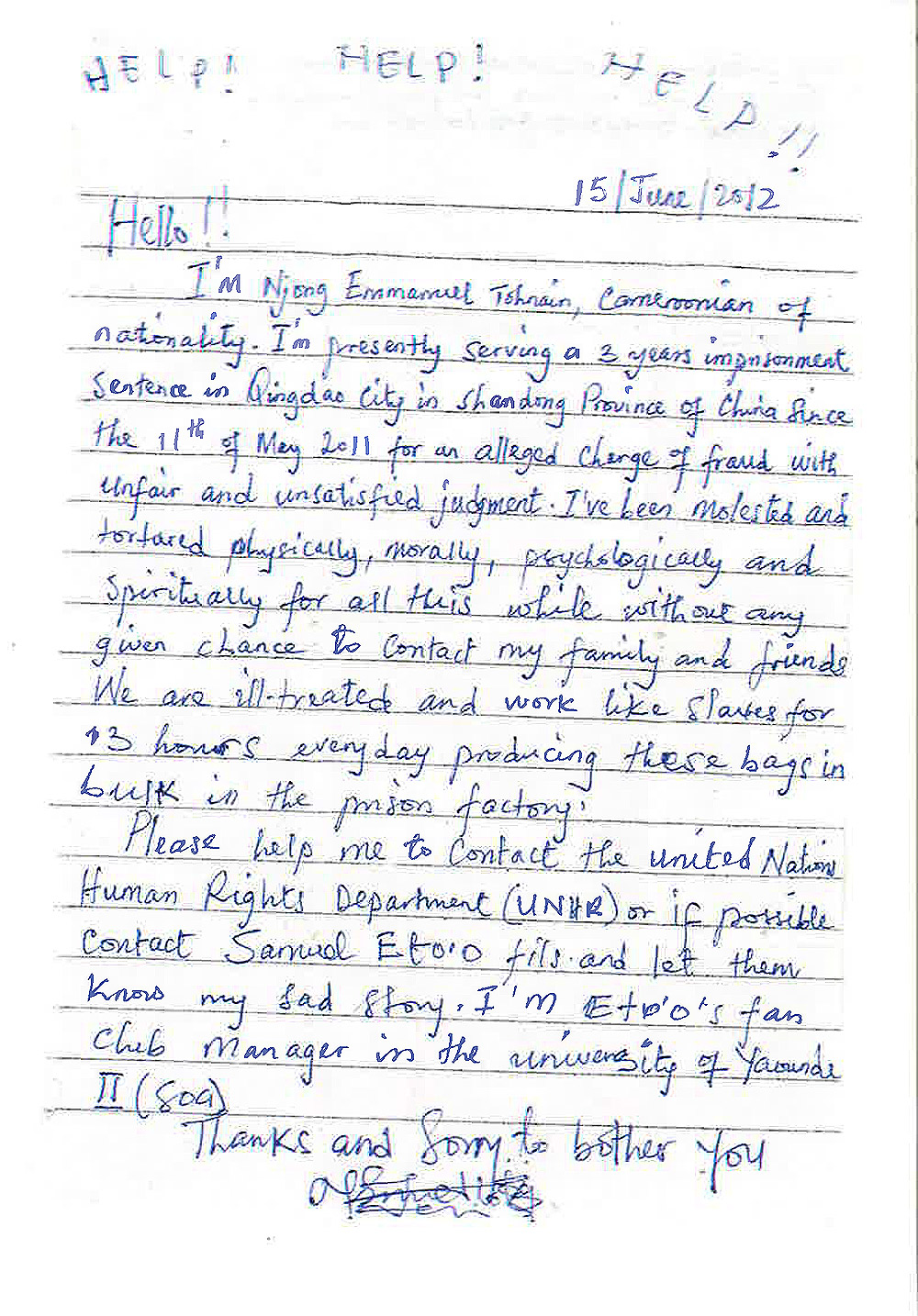

In September, 2012, Stephanie Wilson, a twenty-eight-year-old Australian who lives in West Harlem, bought a pair of Hunter rain boots from Saks Fifth Avenue. She was digging for her receipt in the paper shopping bag when she discovered a letter inside that, in its urgency, started higher than the ruled paper’s printed lines. “HELP! HELP! HELP!!” a man had written, in blue ink on white paper. He opened, “Hello!! I’m Njong Emmanuel Tohnain, Cameroonian of nationality.”

The writer explained that he had made the bag while captive in a Chinese prison factory, where he was being held after an arrest on accusations of fraud. He wrote, “I’ve been molested and tortured physically, morally, psychologically and spiritually for all the while without any given chance to contact my family and friends. We are ill-treated and work like slaves for 13 hours every day producing these bags in bulk in the prison factory. Please help to contact the United Nations Human Rights Department or if possible Samuel Eto’o and let them know my sad story. I’m Eto’o’s fan club manager in the University.” He signed off, politely, “Thanks and sorry to bother you.”

Wilson contacted the Laogai Research Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group established by a survivor of a Chinese slave-labor camp (or laogai) named Harry Wu. Over the following months, the foundation’s legal arm and Serena Solomon, a reporter from the local-news Web site DNAinfo, located Njong’s attorney and his newly activated Facebook account. (He was released from prison last year.) Together, they were able to contact Njong and verify that he had written the letter and determined—based on their investigations online and in China—that the details of his account checked out. (They are also consistent with other accounts of prison labor, Cole Goodrich, the legal consultant at the Laogai Foundation, told me.) The Laogai Foundation identified the company that exported Njong’s shopping bags to the U.S. as Elegant PrinPac. That firm touts its work for Calvin Klein and Polo, its “environmentally friendly products,” and its “quality management system.” (Elegant PrinPac has not replied to requests for comment.)

Solomon published a story about Njong’s letter in April. I contacted Saks and its owner, Hudson’s Bay Company, to ask about the letter and Saks’s supply chain. A spokeswoman named Tiffany Bourré replied that the company has “investigated the matter” but was unable to determine whether Njong’s letter was authentic and accurate, owing to “the lack of information and significant time delay between the discovery of the letter by the customer and notification to Saks more than a year later.” Bourré said that the company prohibits slave labor and has measures in place to avoid its use in Saks’s supply chain, such as audits, which are sometimes unannounced, and a requirement that international venders and suppliers follow laws barring forced labor. I asked whether Saks had changed its practices in response to Njong’s letter, and she answered that it hadn’t, though it was modifying some policies as part of its integration into Hudson’s Bay, which acquired it last year.

Recently, I spoke to Njong myself. He is thirty-four and lives in Dubai, and has an animated and intelligent manner by phone. Njong was raised in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, and learned both English and French while growing up. He said that, in May, 2011, he had been teaching English in Shenzhen, China, when he was arrested on accusations of fraud, which he said he never committed, and held in a detention center for ten months. Later, he was moved to Qingdao, in the eastern Shandong province, for a three-year prison sentence. He had picked up Chinese while teaching, and so he translated while locked up, whenever the prison authorities tapped him. Most of the time, he sewed clothes, assembled electronics, and made bags. “It was tiring and boring at the same time,” he said of the work. Eventually, he and another African prisoner grew so desperate that they decided they’d rather be killed than continue. “If I have to die, I don’t care now,” he told the guards. “I prefer not to get back to the world.”

Njong says that he was permitted no outside contact, and was allowed pen and paper only to record productivity. His family figured he was dead. Although he was constantly monitored, Njong resolved to reach the outside, to put a trace of himself into the products he fabricated “that were going to be exported to other countries like the U.K. and the U.S. and Australia and Germany.” He figured, “If someone could ever hear me somewhere, maybe somebody, in the course of using, could come to the letter and come to my rescue.” The letter that Wilson found was one of five—in either French or English—that he stuffed into bags during his imprisonment. He crawled under his bed covers to scribble.

April marked the one-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than eleven hundred garment workers—the worst industrial accident in the modern garment industry. The disaster led to an uptick in social concern about manufacturing. It also led to changes: more frequent inspections, new regulations, investigations by news outlets into the history of our clothes, plus nifty new consumer-responsibility apps. But forced labor like what Njong says he endured has gotten far less attention.

Unfree labor has, of course, existed throughout history. In 1957, the International Labour Organization adopted a formal resolution abolishing forced labor worldwide. Today, the organization estimates that at least 12.3 million people, globally, are victims of compulsory labor. China’s system of prison facilities, established in the early fifties by Mao Zedong, is particularly massive. Chinese camps, tethered to a notion that criminality springs from ignorance, stress moral instruction and reëducation through labor. According to a tally of industries on the U.S. Department of Labor Web site, the Chinese industries that use forced labor include those making artificial flowers, bricks, Christmas decorations, coal, cotton, electronics, fireworks, footwear, garments, nails, textiles, and toys.

Kevin Slaten, the program coordinator at the human-rights organization China Labor Watch, told me that a number of letters like Njong’s have surfaced in recent years. Last June, the Times reported on one, folded into a pack of Halloween decorations bought at an Oregon Kmart, which read, “Sir: If you occasionally buy this product, please kindly resend this letter to the World Human Right Organization.” At the time, a spokesman for Sears Holdings, which owns Kmart, told the reporter, Andrew Jacobs, that “an internal investigation prompted by the discovery of the letter uncovered no violations of company rules that bar the use of forced labor.” Slaten argues that American corporations, to meet their profit goals, have developed a convoluted system of contracting and subcontracting that is designed “in a way that allows them to plead ignorance” about labor problems. TheU.S. Tariff Act of 1930 bars the inflow of goods made with forced labor—but the law contains a “consumptive demand” exception, which allows goods, even if they are made by forced laborers, to be imported if the demand from consumers can somehow not be met otherwise.

There have been some efforts to reduce forced labor. Kenneth Kennedy, a senior policy adviser on forced-labor programs for the Department of Homeland Security, told me by phone that the U.S. and China have an unusual memorandum of understanding on prison labor. Signed under President George H. W. Bush in 1992, before China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, the agreement prohibited the importation of goods made by Chinese prison labor, and set terms for reports on and investigations of “companies, enterprises or units suspected of violating relevant regulations and laws” made “upon the request of one Party.” The Clinton Administration, in 1994, elaborated on the agreement, requiring the Chinese government to respond within ninety days to a U.S. government request to visit a factory (and vice versa).

“Those two documents are fairly unique,” Kennedy explained. “We don’t have them with other countries.” The United States cannot enforce its own labor laws overseas, but if commodities coming into the United States are found to be produced by prison, forced, or indentured labor, it can impose various penalties—financial and criminal—on the companies importing the commodities. (In 2001, the Allied International Manufacturing (Nanjing) Stationery Company Ltd. pleaded guilty to federal charges of forced prison labor, becoming the first Chinese company in the U.S. so convicted. Kennedy told me that the stationery firm faced financial penalties.) But China, Kennedy explained in an e-mail, cannot be penalized directly for the production of such products. Kennedy didn’t know of any instances in which the U.S. government sent investigators to factories in China and found evidence of forced or prison labor. He declined to comment on Saks because the government considers the case open. (When I asked for clarification, Justin Cole, a spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, who had helped arrange my conversations with Kennedy, said that he “will not be able to comment any further on the case.”)

There’s also change on the other side of the supply chain. Late last year, China’s Parliament voted to end its fifty-five-year-old system of “Reëducation Through Labor” camps. But these camps already regularly break the law—for instance by practicing torture—so human-rights groups remain skeptical. Amnesty International believes that extrajudicial jails and drug-rehabilitation centers are the new sites of punishment for political and religious dissidents. It still falls to courageous individuals like Njong to risk abuse and violence, Solomon Northup-like, in trying to make themselves heard.

Njong told me that he was discharged from prison last December, escorted to Beijing, and put on a plane to Cameroon. He got a two-month tourist visa to go to the United Arab Emirates—renewable once—after borrowing five thousand dollars from a cousin. Over the phone, I asked Njong why he didn’t stay in Cameroon after his return from China. He explained that he left in the first place because of his home country’s swelling corruption. “Dubai was the place I could obtain a visa as fast as possible,” he said.

Njong found work at a cleaning company in Abu Dhabi. “We get up so early, four o’clock,” he told me. “The company acts like brokers: they get workers and send us to locations. My location is a veterinary hospital. We go in the morning and we clean—the animal waste.”

He doesn’t talk often with his family. “Making calls from here is expensive,” he said. “And I’m still waiting for my first salary. I never want to tell them when things are rough. I’m just struggling with my life to see that anything good can come from life.”

I asked about whether he might be compensated for his troubles. Doesn’t China owe him? Don’t any of the others along the supply chain that brought the bag into Stephanie Wilson’s hands? “I don’t think the hours are worth it, seeking compensation,” he said. “It’s not easy. It’s not something anybody can just do.”

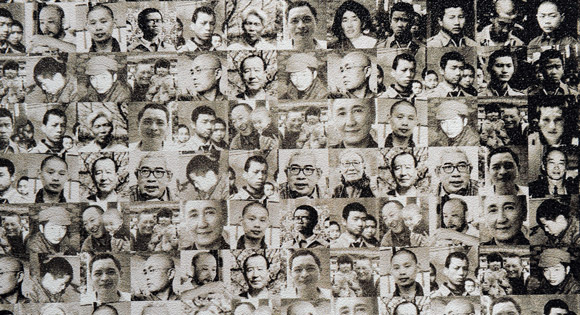

Top: a mosaic of labor-camp prisoners in China at the Laogai Museum in Washington, D.C. Photograph by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post/Getty. Tohnain Emmanuel Njong’s letter courtesy of Stephanie Wilson.