May 12, 2013

Dark Room Collective: Essay

By Sharan Strange

When James Baldwin died in 1987, a group of Cambridge, Massachusetts housemates—among us, aspiring writers and filmmakers—made a pilgrimage to his funeral in New York. It was winter and typically dreary when we heard, and though we were stung by the news of death, we felt a sense of urgency, a need to go and be among the mourners, to acknowledge his passing in a communal way. As we made our way by car to Baldwin’s native city, each of us reflecting, perhaps, on what his life and work had meant to us, amid the somberness of that occasion sat the stark realization that he was truly lost to us. He’d been here among us all those years; I had even attended a tea at Harvard and stood in the same room with him, too shy to break through the thick clot of fans around him and offer the admiration he had been accustomed to for decades. Now he was gone and we could never hear him speak his words in person, never have a conversation with him, never clasp his hand. We had read the biographies and critical studies and knew what a complex, reputedly difficult figure he was. But he was our brilliant treasure; we had claimed him and we went to pay our respects.

……………………………………………………………………….

This essay first appeared in Mosaic #16, Fall 2006

……………………………………………………………………….

The funeral was a literary event, like a reading or book party. All our literary icons were there. Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, and Amiri Baraka eulogized Baldwin, and it was thrilling to hear Baraka describe him as “God’s own revolutionary black mouth.” It was something no funeral is supposed to be: a heady affair. Yes, we went to say farewell to “Jimmy,” but our sense of loss couldn’t truly match that of the people who had actually known him. We felt somewhat like distant young cousins of a family patriarch whose passing we felt as momentous but could be met without the deepest sorrow for we had known him only from a distance. Instead, our sorrow was suffused with a kind of energy, a desire to make something positive out of loss, and so we resolved that we wouldn’t let another of our literary elders get away from us. In traditional Black culture elders are always teachers, role models. Through his writings and activism, his humanism and his vision, Baldwin had given us an example of passionate engagement with life. Like the griots of West African culture, he and other Black writers bear witness to our collective struggles and survival. And like countless other writers before them, they have made vital contributions to American literature and the African American artistic tradition. We wanted to affirm the sustaining value of their commitment and acknowledge our debt to them. So we left St. John the Divine Church in Harlem and went back to Cambridge with an idea.

Upon our return, my housemate Thomas Sayers Ellis and I began to make plans to formally connect with and honor other still-living Black writers, whom we dubbed our “living literary ancestors.” We were already involved in a project of building an extensive library of writings by Black authors of the Diaspora, including first editions and out-of-print publications. We had named it “The Dark Room: A Collection of Black Writing” because it was housed in a former photographic darkroom on the third floor of the old Victorian house we shared with four other artists/students in Central Square. The words were already emblazoned on the door and we liked the pun it provided on a room full of “black books.” The metaphor of a darkroom was also apt: a place where images develop, brought forth in darkness into light. Incubator. Womb. Only afterwards did we realize the affinity with the Dark Tower—named after Countee Cullen’s poem—the gathering of Harlem Renaissance artists in A’lelia Walker’s salon.

In the spring of 1988 we began planning the Dark Room Reading Series. Ellis and I had been attending readings around Boston and Cambridge where we heard many of the luminaries that such an intellectual center draws, but we noted the paucity of Black writers and other writers of color invited to read at those events. Yet Derek Walcott was teaching at Boston University and Samuel Allen was emeritus professor there. Ishmael Reed was visiting at Harvard. Other well-known writers were to be found at outposts in western Massachusetts and other nearby New England communities. Why weren’t they more frequently seen? And what about the not-so-celebrated writers who were doing good work? Didn’t the curators of those reading series peruse the bookstores or the journals? Or was it considered too difficult to bring those folks to town—to Cambridge, a place with deep intellectual, cultural, and financial resources? That could hardly be the case. Or, was there a disdain for or, perhaps worse, sheer lack of interest in any but the most celebrated, established writers of color? Local emerging writers also seemed to go unnoticed by the curators of series at the public libraries and university English and writing departments. Who would nurture and promote their work? Ellis and I had discovered numerous writers in journals and on bookstore shelves and we had become acquainted with several local writers. We wanted to hear them read their words, have conversations with them, clasp their hands. We wanted them to know that their work was appreciated, was inspiring, was changing lives. We wanted to know them and to have them know us.

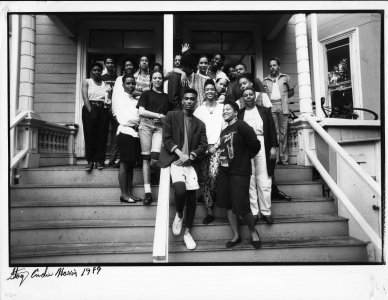

During that time we met Janice Lowe, a musician who also wrote poems, and she joined us, agreeing to organize art exhibits to accompany the readings. We also met Jon Ewing, a journalist who was enthusiastically absorbing the writings of Primo Levi and trying his hand at experimental prose; he also joined us. And by March 1989—after treks across the river to invite Walcott to read in our living room; to Brown University in Providence to coax Michael S. Harper (whom we greeted with the following message from Walcott: “I command you like a West Indian general to read for these people!”); to New York to meet Clarence Major; to our “backyard” (Harvard) to talk with Reed; to Tufts to meet Baraka; to Brandeis to meet Morrison; to Amherst to meet Samuel Delany and John Wideman; and to the Victor Hugo Bookstore in Boston’s Back Bay to meet Sam Cornish, just some of the “headliners” we photographed and hoped would sign on to the venture—we had created a reading series that eventually went beyond our initially modest and somewhat selfish goals. We reached out to writers, artists, musicians, journalists, editors, critics, arts organizations, academic institutions, activists, merchants, students, and just plain folks. We met on Sunday afternoons after church and for some of us it was church. Clarence Major’s succinct declaration became our anthem and benediction: Total life is what we want! Ultimately, the series helped to create a diverse artistic community where before a void had existed. And we noted, with great satisfaction, the reverberations beyond our house: other collectives were formed, new reading series sprang up, and Black writers started to come out of the woodwork.

In two seasons at our house at 31 Inman Street—which began with readers Quincy Troupe and Dorchester’s Darryl Alladice and ended with Terry McMillan and Danielle Legros-Georges—numerous readings paired established and emerging writers such as Walcott, Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange, Yusef Komunyakaa, Samuel Delany, Toni Cade Bambara, John Wideman, Dolores Kendrick, Dennis Brutus, Martín Espada, Elizabeth Alexander, Randall Kenan, Pearl Cleage, Trey Ellis, Essex Hemphill, Melvin Dixon, Patricia Spears Jones, Pat Powell, Michael Thelwell, Cornelius Eady, Carolivia Herron, Barbara Neely, Cyrus Cassells, Sam Cornish, Carolyn Beard Whitlow, Tim Seibles, Xam Cartier, and Kate Rushin, among others. Painter Ellen Gallagher, then a student at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts whom we met on the bus to Providence on our way to meet Harper, also joined us to curate our exhibitions of established and rising local artists, among them Bryan McFarlane, Ife Franklin, Vusumuzi Maduna, Roxanne Perenchief, and Kirstin Gabler. Two highlights of the second season were a marathon reading of Bob Kaufman’s works as a tribute to the late North Beach poet who coined the term “Beat poetry,” and an evening of collaboration and reminiscences by three long-time friends—novelist Leon Forrest, sculptor Richard Hunt, and composer T.J. Anderson, Jr.—at the historic African Meeting House in Boston.

As we reached out to claim and nurture our literary avatars, many of them reached out to us first: Scholar and critic Mary Helen Washington was an enthusiastic friend who brought us Alice Walker and Toni Cade Bambara, who both had sought out our series because they wanted to support our efforts. Both read without demanding an honorarium—as did Walcott, as did the other writers in those beginning seasons when we had to pool our meager finances to pay for airfare, hotels, and the group dinners that usually capped the day. One day we got a call from Gloria Joseph who had heard about our book collection and wanted to contribute several boxes of books that she and Audre Lorde had amassed in St. Croix. The energy flowed in both directions between us and our ancestors and elders. We received crucial assistance in other ways too: Callaloo editor Charles H. Rowell, a long-time champion of our cause, agreed to introduce Terry McMillan in the final reading at the Inman Street house, and later solicited our work for publication in the journal. And Don Lee, editor of Ploughshares, volunteered the journal as a fiscal sponsor for the grants that helped the series to transition to a larger venue.

With listeners spilling out into the hallway, stairs, and front porch, the readings eventually outgrew our living room. The series then moved to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston where our mission became twofold: to continue to build community around our celebration and support of Black and other artists of color, and also to make the museum more accessible to certain communities that it had failed to connect with in the past. The larger space—and funding to pay the writers—allowed us to accommodate our growing audiences, but it lacked the afro-bohemian flavor, the informal hospitality that we had cultivated at Inman Street. So we added a jazz band, Salim Washington and the Roxbury Blues Aesthetic, to the mix. Michael Harper, Al Young, Nathaniel Mackey, Harryette Mullen, Thylias Moss, Walter Mosley, Greg Tate, Arthur Jafa, Toi Derricotte, Helen Elaine Lee, Carl Phillips, Paul Beatty, and Natasha Tarpley were some of the featured readers. Radcliffe’s Bunting Institute director Florence Ladd (mother of poet Michael Ladd), film scholar Clyde Taylor, and Northeastern University professor (at the time) and literary archivist Maryemma Graham, among others, became patrons. We also incorporated another way of paying tribute with the Dark Room Awards—original works of art by Vusumuzi Maduna and Benny Andrews —given to Yusef Komunyakaa and Thylias Moss for poetry, and to Samuel R. Delany for fiction.

In its final season in 1994, the Dark Room Reading Series moved to the Boston University Playwrights’ Theatre (then under the direction of Walcott). By the time the series came to a close, we had added discussions by playwrights and talks by cultural critics to our usual offerings of poetry and prose fiction, with readers such as Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Afaa Michael Weaver, Erica Hunt, David Henderson, Shay Youngblood, Marilene Phipps, Dominic Taylor, and Willie Perdomo. In the short span of five years we had hosted over 100 writers, not to mention numerous visual artists and musicians. We weren’t organizing poetry slams but we were similarly populist in our ethos. We wanted to make room for more voices and to provide a venue where we could begin to diminish those common barriers to appreciation of a broader spectrum of voices: biases around race, class, gender, sexuality, culture, ideology, etc. What started as an “underground” venture, so to speak, may have capitulated to the museum and the university in the end, but not, I think, without changing those places in important ways.

The most discernible changes, however, were in our individual lives as writers. Our original band of four had not anticipated the overwhelming response the series would get, and after our inaugural season it became clear that we needed more support. Thus we conceived of a collective of young writers who would pay dues, literally and figuratively, by organizing the series and nurturing and learning from each other as artists. The Dark Room Collective formed in our second season, when we began to alternate our weekly public readings with critique sessions for a small group of earnest aspirants to that literary pantheon we were hosting. New members joined in rapid succession; some we had met at literary events as we scouted the town for readers; others had seen our neon-bright posters modeled after the go-go show posters of Ellis’s native D.C., or received the homemade flyers and cards I had designed and which we gave out all over town; others had returned to the series week after week, lured by the sharing, fun, and serious purpose that infused the atmosphere. Some of us had been writing in virtual isolation for years; some were currently in writing classes at Harvard and other schools; some, like myself, had begun to write seriously only as a result of being involved in the Dark Room. The Collective, then, became a catalyst for a higher level of engagement with writing and nourished a hunger we all had for affirmation of our incipient steps as writers—not just from peers, but from our elders, those “living literary ancestors” that we had begun to dialogue with through the reading series. Thus began our real apprenticeship—the reading series and our workshops were in a sense our true MFA writing program. Later, as we grew in craft and confidence, we traveled and read our works together, incorporating a ritual of honoring our literary ancestors at each of our presentations.

The Collective readings helped not only to keep us connected as we increasingly dispersed to pursue graduate study, fellowships, jobs, and various creative endeavors, but they also allowed us to expand our notion of writing community as we met and read with peers in other places. Our first official reading as a collective, in August 1990, was number 101 in the Ascension Reading Series organized by E. Ethelbert Miller in Washington, D.C. We went on to establish relationships with, and read at programs hosted by, other writers’ groups on the thriving ‘90s literary scene in Chocolate City: the 8-Rock Collective of Anacostia (Kenneth Carroll, Brian Gilmore, Judy Cohall, and DJ Renegade) and the Modern Urban Griots, whose members included Toni Asante Lightfoot, Holly Bass, and Brandon Johnson, and whose hugely popular open mic sessions at the It’s Your Mug café filled Georgetown’s streets in the evenings with young Black folks.

We also found community in Philadelphia, meeting writers associated with Twelfth House—Major Jackson and Nehassaiu de Gannes (both later joined the Collective) and Ursula Rucker, among others—and reading at the Painted Bride, with an introduction by Ntozake Shange who had graciously put the whole Dark Room Collective up at her house! In our informal gatherings at the Brooklyn apartment of Naadu Blankson and at venues like mosaicbooks, Blackberry’s, and the Nuyorican Poets Café, we met and read with Paul Beatty, Asha Bandele, Kevin Powell, Tish Benson, Willie Perdomo, Sabah as-Sabah, Tony Medina, Tracie Morris, and other New York writers and artists. And at the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta we made connections with Midwest writers Jabari Asim, Ira Jones, and Andrea Wren—younger associates of literary elder and mentor Eugene Redmond—who curated programs at the Vaughn Cultural Center in St. Louis and solicited some of our writings for Eyeball and Young Tongues, publications of their First Civilizations Press.

But the high point of all that traveling and bonding was the first Furious Flower Conference, which celebrated the Black poetic tradition and, in particular, the life and work of Gwendolyn Brooks. Convened at James Madison University in the fall of 1994 by Dr. Joanne V. Gabbin—former student of Sterling Brown and scholar of his work and Brooks’s, among others—the conference brought together authors, scholars, and publishers of Black poetry from across the country, the generations, and the broad spectrum of voices, from publishing pioneers like Naomi Long Madgett to icons of the Black Arts Movement to their inheritors. Members of the Dark Room were ecstatic to be invited to participate in such a watershed event in African American literary history and to share the stage with writers whom we had cut our teeth on.

After giving readings and workshops from Maine to Miami over the course of almost a decade, the last performances by the Collective were the Drive-By Readings of 1996-1998. By then we had become a solid ensemble of readers, attuned to our individual strengths and the ways in which we complemented and supported each other. With more stylized programs that incorporated “sets” of our works, props, music, and intermissions we were able to offer our audiences the diversity of our voices with a bit of the flair that characterized our original reading series.

Now nearly twenty years later, the Dark Room Reading Series has extinguished its lights and the Dark Room Collective has scattered to different states and countries. But the work begun there continues. Former Dark Room members have published and continue to publish collections of their poetry and prose, edit anthologies, teach writing workshops and literature classes, give public readings and lectures, read and advise at major journals, and curate reading series. With the abiding spirits of James Baldwin, Bob Kaufman, Audre Lorde, Ralph Ellison, Melvin Dixon, Leon Forrest, Margaret Walker Alexander, Pat Parker, Toni Cade Bambara, Essex Hemphill, Sabah as-Sabah, Sherley Anne Williams, Dudley Randall, Barbara Christian, Gwendolyn Brooks, Raymond Patterson, Tom Dent, Safiya Henderson-Holmes, Ted Joans, Pedro Pietri, Thomas Grimes, June Jordan, Lorenzo Thomas, and the host of their—and our—literary forebears, we continue a rich legacy, naming and claiming our own.

The Dark Room Collective (1989-1998)

Thomas Sayers Ellis (The Genuine Negro Hero; The Maverick Room), Sharan Strange (Ash), Janice Lowe, Jon Ewing, Tisa Bryant (Tzimmes), Trasi Johnson, Aya de León (Live at La Peña), Della Scott, John R. Keene (Annotations), Rich Britton, Donia Allen, Donette Wilson, Patrick Sylvain, Danielle Legros-Georges (Maroon), Artress Bethany White, Tracy K. Smith (The Body’s Question), Kevin Young (Most Way Home; To Repel Ghosts; Jelly Roll; Black Maria), Murad Kalam, formerly Godffrey Williams (Night Journey), Kambui Olujimi, Carl Phillips (In the Blood; Cortège; From the Devotions; Pastoral; The Tether; Rock Harbor; The Rest of Love), Muhonjia Khaminwa, John Searcy, Gina Dorcely, Maya Trotz, Nelly Rosario (Song of the Water Saints), Ellen Gallagher (Blubber; Preserve; Exelento; Murmur), Salim Washington, Adisa Vera Beatty, Major Jackson (Leaving Saturn; Hoops), Natasha Trethewey (Domestic Work; Bellocq’s Ophelia; Native Guard), Nehassaiu de Gannes (Percussion, Salt & Honey), Audrey Petty, David Wright (Fire on the Beach), Jahmae Harris.

The Dark Room Extended Family

Noland Walker, Kelly Sloane, Sonya Brown, Stacey André Harris, Maritza de Campos, Bethany van Delft, Dina Strachan, Jade Barker, Jorge Otaño, Mackie Burnett, Kevin Keels, Philecia Harris, Blondel Joseph, Toni and Wyatt Jackson, Mark Leong, Marcus Alonso, Vuzi Maduna, Mark Griffith, Charles Rowell, Ntozake Shange, Clyde Taylor, Mary Helen Washington, Maryemma Graham, Richard Hunt, Florence Ladd, Joanne V. Gabbin, Askold Melnyczuk, William Corbett, Kay Bourne, Don Lee, Eve Stern, André Caple, Yvette Mattern, Kwaku Alston, Jacquie Jones, Gelonia Dent, and many more.