Bengali Harlem and

the Lost Histories

of South Asian America

HARDCOVER$35.00 • £25.95 • €31.50

ISBN 9780674066663

Publication: January 2013

x Text

320 pages

6-1/8 x 9-1/4 inches

15 halftones, 2 maps, 4 tables

Listen to Vivek Bald discuss his Bengali Harlem project with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer:

In the final years of the nineteenth century, small groups of Muslim peddlers arrived at Ellis Island every summer, bags heavy with embroidered silks from their home villages in Bengal. The American demand for “Oriental goods” took these migrants on a curious path, from New Jersey’s beach boardwalks into the heart of the segregated South. Two decades later, hundreds of Indian Muslim seamen began jumping ship in New York and Baltimore, escaping the engine rooms of British steamers to find less brutal work onshore. As factory owners sought their labor and anti-Asian immigration laws closed in around them, these men built clandestine networks that stretched from the northeastern waterfront across the industrial Midwest.

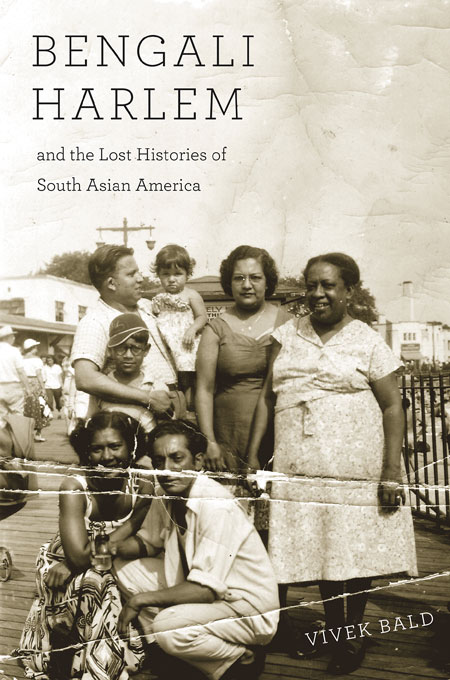

The stories of these early working-class migrants vividly contrast with our typical understanding of immigration. Vivek Bald’s meticulous reconstruction reveals a lost history of South Asian sojourning and life-making in the United States. At a time when Asian immigrants were vilified and criminalized, Bengali Muslims quietly became part of some of America’s most iconic neighborhoods of color, from Tremé in New Orleans to Detroit’s Black Bottom, from West Baltimore to Harlem. Many started families with Creole, Puerto Rican, and African American women.

As steel and auto workers in the Midwest, as traders in the South, and as halal hot dog vendors on 125th Street, these immigrants created lives as remarkable as they are unknown. Their stories of ingenuity and intermixture challenge assumptions about assimilation and reveal cross-racial affinities beneath the surface of early twentieth-century America.

>via: http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674066663

__________________________

“Searching for a Name”

by Fatima Shaik

A guest post from Fatima Shaik, a New Orleans writer whose grandfather Shaik Mohamed Musa was one of the group of “Oriental goods” traders who came from Hooghly, West Bengal to the U.S. South in the 1890s. (Read more about Fatima at the end of the post.)

The New Orleans telephone book annually hit our wide, wooden front porch with a thud in the 1950s and 60s. Every year, I rushed to bring the book inside and look for our last name. The result was always the same – only one Shaik family lived in the city and we were further isolated by my father’s first name, Mohamed.

Still, I thumbed through the tissue sheets to find names that sounded similar – Shaak, Shank, and Shakesynder — thinking that perhaps they might be some version of ours in the same way that my father – an unrelenting educator – told me that Boudreaux and Boudreu came from the same Cajun root. But never did I find names that were similar to ours.

Once in the back of the house, I handed the phone book to my father. He mimicked my excitement and disappointment – one Shaik year after year. You would think by then he would have stopped searching.

But his emptiness went far deeper than mine. He was the only son of a Bengali Muslim father who had disappeared. New Orleans, a port city, had a reputation for absent sailor and soldier fathers – and not always for reputable reasons.

Plus, we lived in segregation, which was not so bad inside our quiet Seventh Ward neighborhood just outside the borders of Trémé, where my father grew up. In reality, it was a mixed-race community. But in those years in the South, there were only whites and Negroes. The first, by common definition, had all the good attributes of humankind and the second had all the bad. So we looked all over for positive reinforcement. My father looked to India.

In India, his father owned land, my grandmother said. In India, his father learned business, which made him successful when he landed in New Orleans – owning a furniture store and pieces of property. With a father from India, my grandmother encouraged my father, he could achieve anything.

Occasionally, he got a phone call from an Asian immigrant, new in town, who saw our name and wanted to know who we were. My father would talk candidly to these complete strangers. He told them about his father who died while his mother was pregnant – the reason his family had no way back. He told them that he believed that Shaik Mohamed Musa came from India before Pakistan was carved out. He said that the Hooghly Village was the place of his father’s birth, although nothing could be located but the Hooghly River. He had lost all contact with the other Indian families that he heard lived in New Orleans because after his father died, his mother returned to her family.

And my father always indicated in some way that he was a Negro – by telling the callers the names of the schools where he taught, about his job as an airplane mechanic at Tuskegee during the war, or some other touchstone that would indicate he was not Indian alone. He didn’t want them to be disappointed, as he expected that they would be. How disappointing to them, he thought, that a man whose family had been in New Orleans, on his mother’s side, probably since before the city existed was still not entirely a citizen. He was not happy either that the coda “Negro” so often appeared before his achievements – Negro schoolteacher, Negro pilot, and Negro Ph.D.

Later, even though my mother and I had overheard his telephone conversation, he would recollect it to us, over and over. He’d telephone his sisters, Haleemon and Noyemon, and tell them about the Indian phone call. He was always wistful after those conversations, thinking that there was a vast sea of unknown relatives – people who might fill up a phone book in some other part of the world.

Had he lived to 2013, he would have been pouring over every line in Vivek Bald’s new book – searching for the names of Indian men and finding familiar black families who lived not far from our neighborhood block, discovering the history of the peddlers from the Hooghly region, getting confirmation of his oral history, and more. When my father died in 2006 at the age of 86, he was just learning to use the internet. He searched maps of the Indian continent.

After he died, I began searching too, in earnest, as one suddenly does after realizing just how much is gone. The hookah, the papers my aunt Haleemon kept, and more washed away in hurricane Katrina. But I still have my grandfather’s diamond stickpin and a few photos. And I have family stories. In March, I am going to bring them to India – finally, in some ways, achieving my father’s dream.

Documentarian Kavery Kaul is taking me to India in her next film. We will journey back to the past. She will frame the scenes that my father should have viewed and my grandfather knew. Hopefully, I am a conduit of their spirits. I was born in New Orleans where spirits exist not just in our memories but in our daily lives. So I’m going to call on my father and grandfather to guide me.

And who knows, maybe I’ll hear of a relative and I’ll take out my cell phone and call him out of the blue.

– – – – – – –

For more information about the upcoming film by Kavery Kaul go tohttp://hartleyfoundation.org/en/streetcar-to-kolkata

Fatima Shaik is an expert on the Afro-Creole experience in New Orleans and an author of books for adults and children. Her work has appeared in the Southern Review, Callaloo, the New York Times, the New Orleans Times-Picayune, and in the anthologies Breaking Ice, Streetlights and African American Literature. She is currently researching the Société d’Economie, a 19th century benevolent association and traveling to India. She is an assistant professor at Saint Peter’s University. More at: www.fatimashaik.com

The picture accompanying this post shows Fatima’s father Mohamed Shaik on his graduation from Xavier University of Louisiana, the sole Catholic HBCU in the United States.

>via: http://bengaliharlem.com/?p=332