GHOSTS

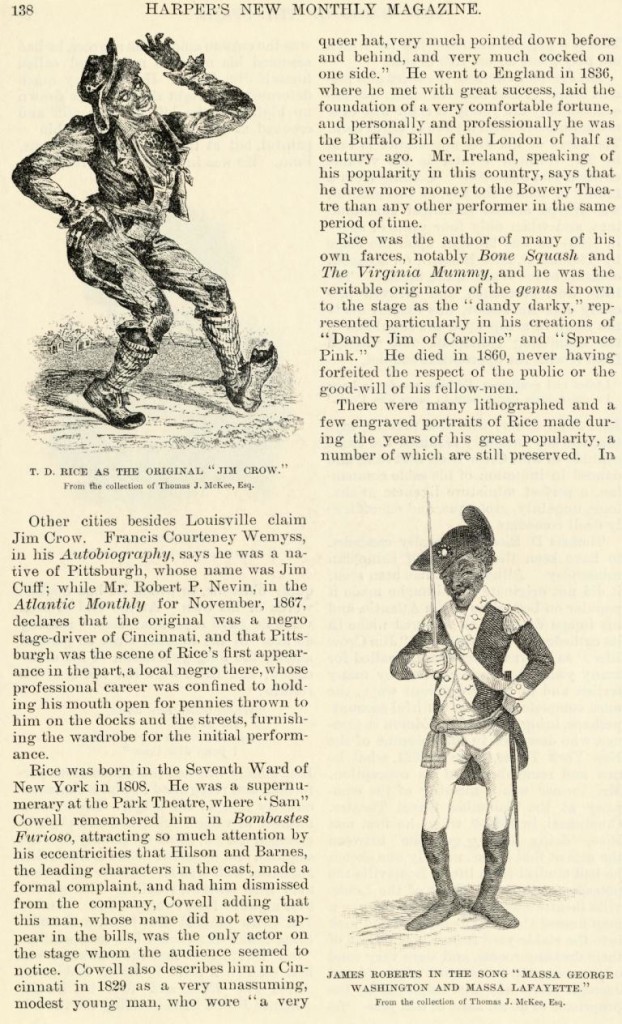

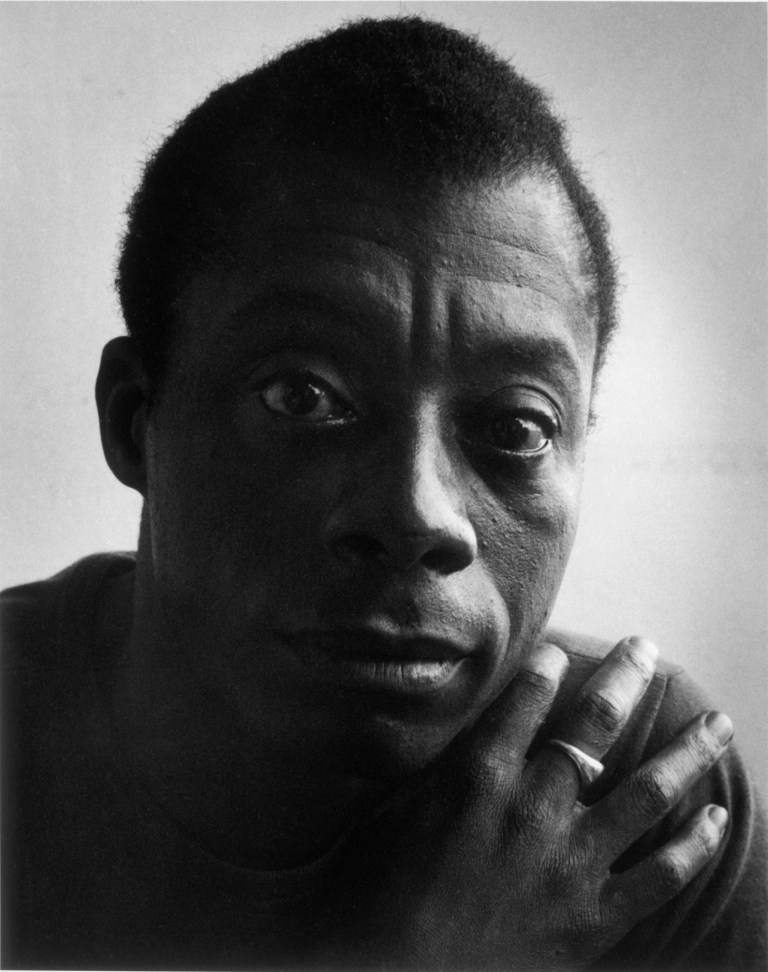

i have the smile of my great-grandmother seeing the end of slavery

& you have the hairline of an uncle/an aunt

who never pressed nor otherwise chemically altered their hair

only fools don’t intimately know ghosts,

the dna of humanity, leaping like porpoises slick out of the sea

and back into our walks, our mannerisms, the way we giggle

when nervous, blush when aroused, or spit fire words

in sputtering ocher anger facing back the cannibalism of capitalism

ghosts are

just spirits fluttering angel breaths thru our corpuscles

the wing hum of hummingbirds motivating us to sound

snatches of remembered songs, lyrics formerly unheard

in this lifetime, psychicly transmuted across eras,

mali melodies maintained, aural treasures from our undying befores

face east young people, face east

imagine each line in your hand an ancestor

how well do you know the thoroughness of yesterday,

the arching influence of the previous century, the retrograde

of rationality, so slow compared to the velocity

of history smashing into the protons of personality

imagine, your voice is the texture of sun yat sen singing

a freedom song, your social erectness the reincarnate posture

of sitting bull standing barefoot his clear eyes kissing dark earth,

imagine, your breath the aroma of emiliano zapata biting the bullet

of revolution and spitting fire on the butts of robber barons

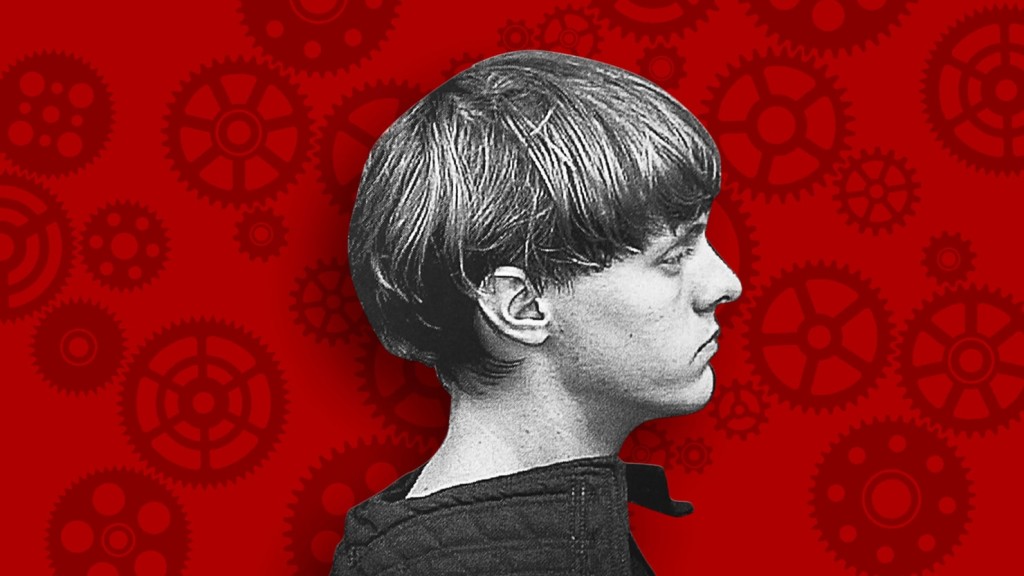

and dark-faced overseers who are the psychological sons

of simon legree in their twisted brutality towards their own people,

the definance of your unsurrendering war stance could be ghana’s

yaa asantewa hurling up the west coast facing down british bullets

confident that the religion of resistance will always outlive

the technology of repression, you could be the heroics of history,

a phantasmagoria of sacred strugglers vivifying the surge

of timeless protoplasm which careens through your veins

and gives substance to the willfulness of your animated engagement

with the omnivorous enemies of the planet earth

ghosts are

sacred illuminations coloring our stratagems and meditations,

they are the realization of sanity, the moment we truly understand

just how wicked the west actually is, the translucent

lights on the front porches of our spirits beckoning, guiding our

soft footsteps on the path, heading back homeward bound

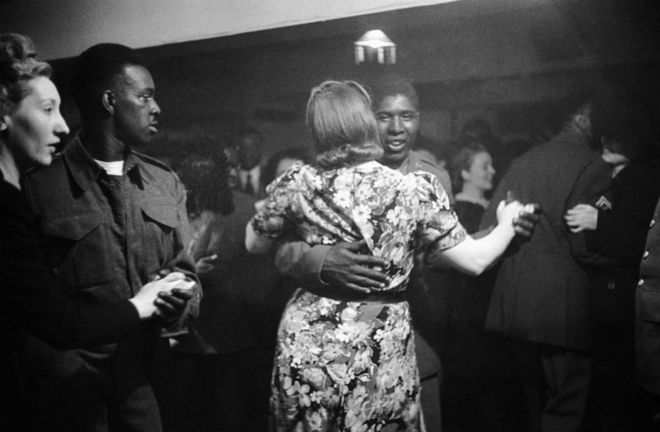

dancing into the social circle of our collective selves

ghosts remind us

each individual is more than one, a communal hope chest

of ancient dreams actualized in the present

i believe in ghosts, i do

because i would be soulless matter otherwise

i would be some french rationalist trying to intellectually manufacture

& market the focus of life as the ego of thought, would be

some compassionless corporate ceo with spiritual arthritis

uninformed by the blessings of sharing, while pretending

that material possessions elevate morality as if you are what you own

rather than are what you do/be in relation to others and the world

ghosts

do not like vaults and crypts, nor fences and forts

real ghosts prefer sensitive personalities and wild open spaces,

every time we inhale a leaf shakes,

a tree or a weed offers us breath

give thanks to the grass for our daily inhalations

i am not a mystic

but i know there are ghosts

in the fecund topsoil which progress

callously covers with concrete,

i understand the reality that dust and dirt are airborne bones

pulverized by time into tiny particles

a rose by any other name is still the collected essence

of our forebearers grown through the life cycle into a fragrant state

of petal soft beauty on a bud whose shape is nature’s re-creation

of the vaginal portal, whose redness is an honoring

of feminine life force and the blood value of matriarchy

if you do not believe in ghosts

where do you think your spirit will be

when the corporeal temple of your familiar

crumbles into seemingly insignificant pebbles of peat, or

when your temporal sanctuary dehydrates

once disconnected from the moisturizing of life’s cosmic juice,

when the way station of your flesh altar no longer receives offerings

& when you revert to what you were before your human being

was conceived and made flesh via the union of your parents,

won’t you be a ghost then?

there are literally millions of lives in your little finger

the karma of colonialism will not be undone

not unless and until the ghosts that reside

in the hosts of color worldwide can find a culture

which resonates daily contentment,

there will be no end to the wandering search for the promised land

unless and until ghosts can live

inside the wholeness of beating hearts synchronized

in embracement, respecting the healing touch

of every manifestation of life no matter how small, obscure,

or ostensibly insignificant,

no calming the tempest,

no mediation of the disruption of our heritage

not unless and until ghosts can emigrate

into a peace filled community of souls such as we

ought to be, vessels of awareness, responsible in our openness

to offer wholesome residences for the motion flow

of history seeking future,

there will always be a wailing issuing out our mouths

unless and until ghosts can live and

comfortably reside, live, and rest inside, rest

in peace, rest in us

ghosts

peace

ghosts

rest

ghosts

in

ghosts

peace

ghosts

rest

ghosts

in

ghosts

us

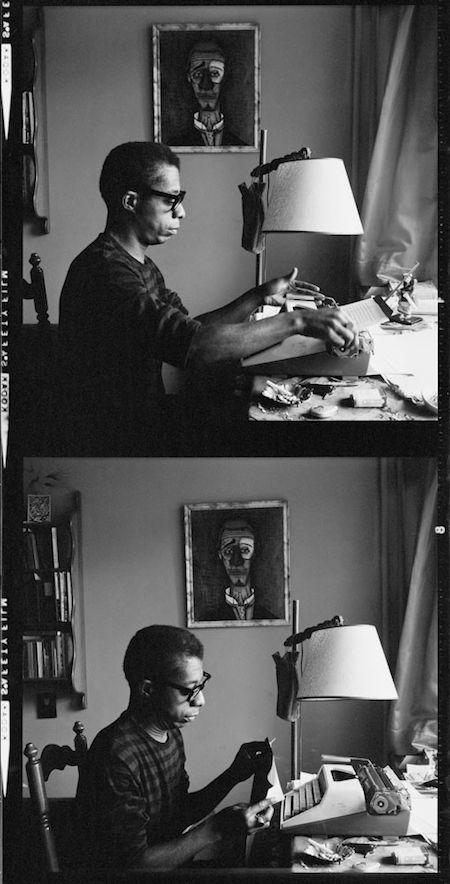

—kalamu ya salaam

______________________

Kalamu ya Salaam – vocals

Stephan Richter – bass clarinet

Wolfi Schlick – tenor & reeds

Frank Bruckner – guitar

Roland HH Biswurm – drums

Recorded: May 31, 1998 – Munich, Germany