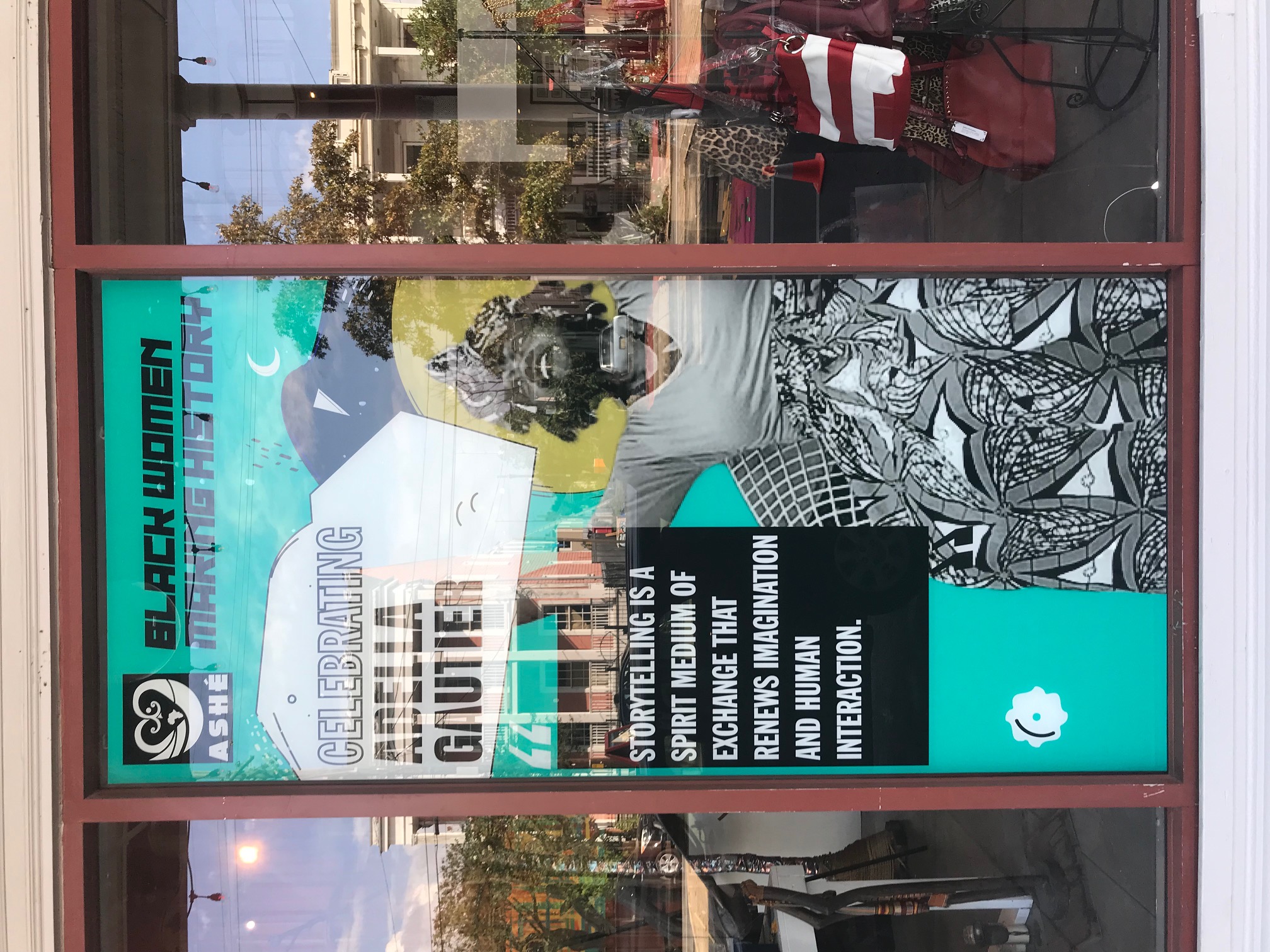

I got up this morning and decided to take in some artwork. I live in the Ashe building, on the second floor in the rear where the apartments are. Photographer (and former high school classmate) Eric Waters had called me the day before, summoning me down to check out the Art of the Black Experience show, a collection of drawings, paintings, sculptures revealing and reveling in who we are and how we got over. I was so glad he had–even though I knew about the program, like most negroes, I needed some encouragement.

Moved by what I had seen the day before when Eric called, I slow walked down four uneven flights of steps and went through the parking lot to the front of the building for a second viewing. I had my iPhone7 in my pocket so I could take and share snapshots of some of the artwork.

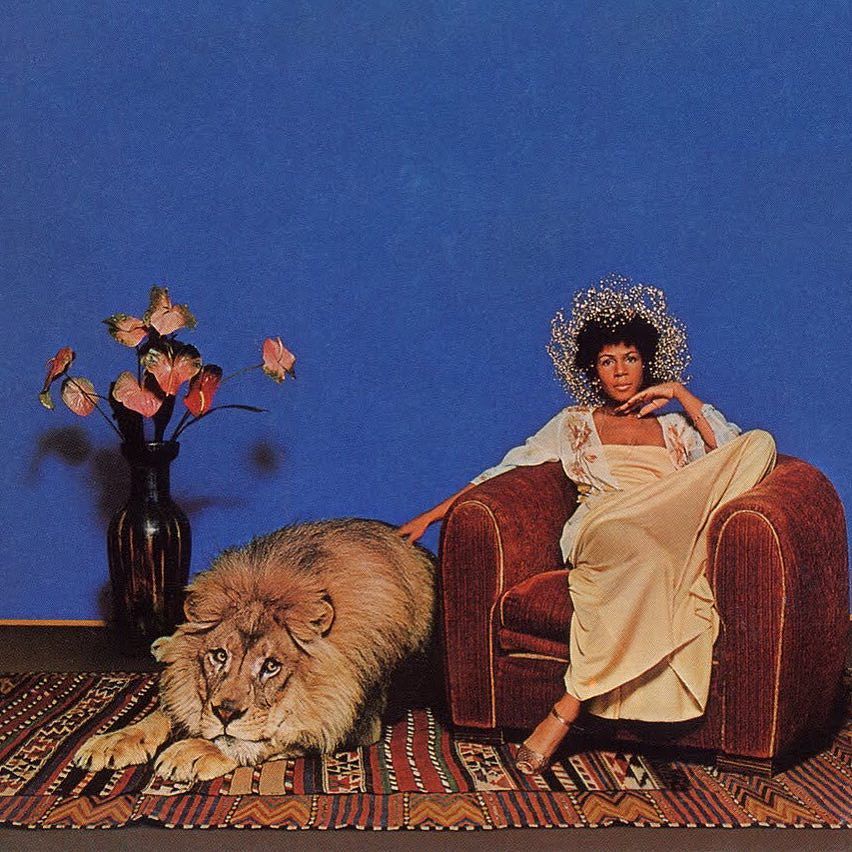

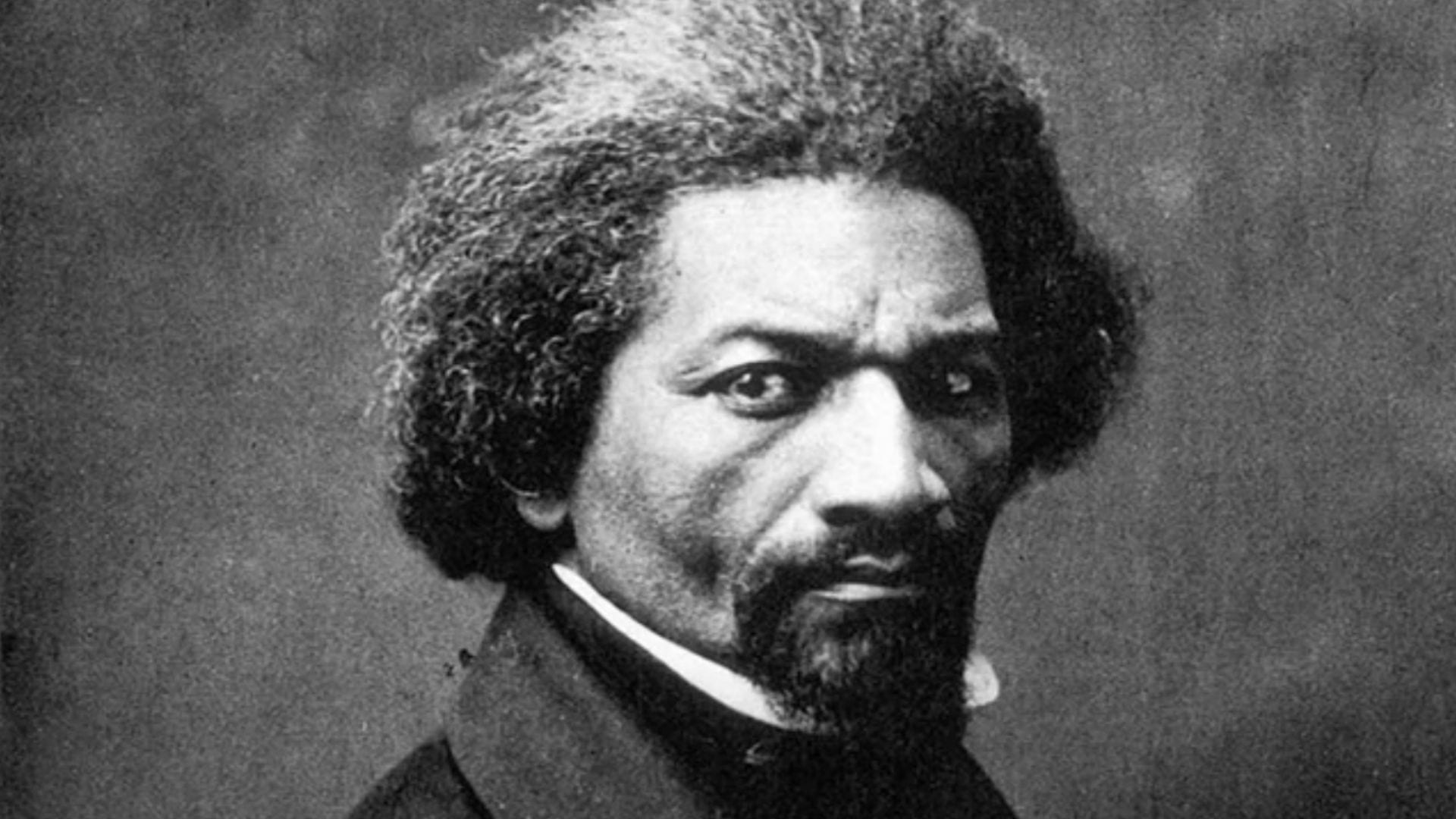

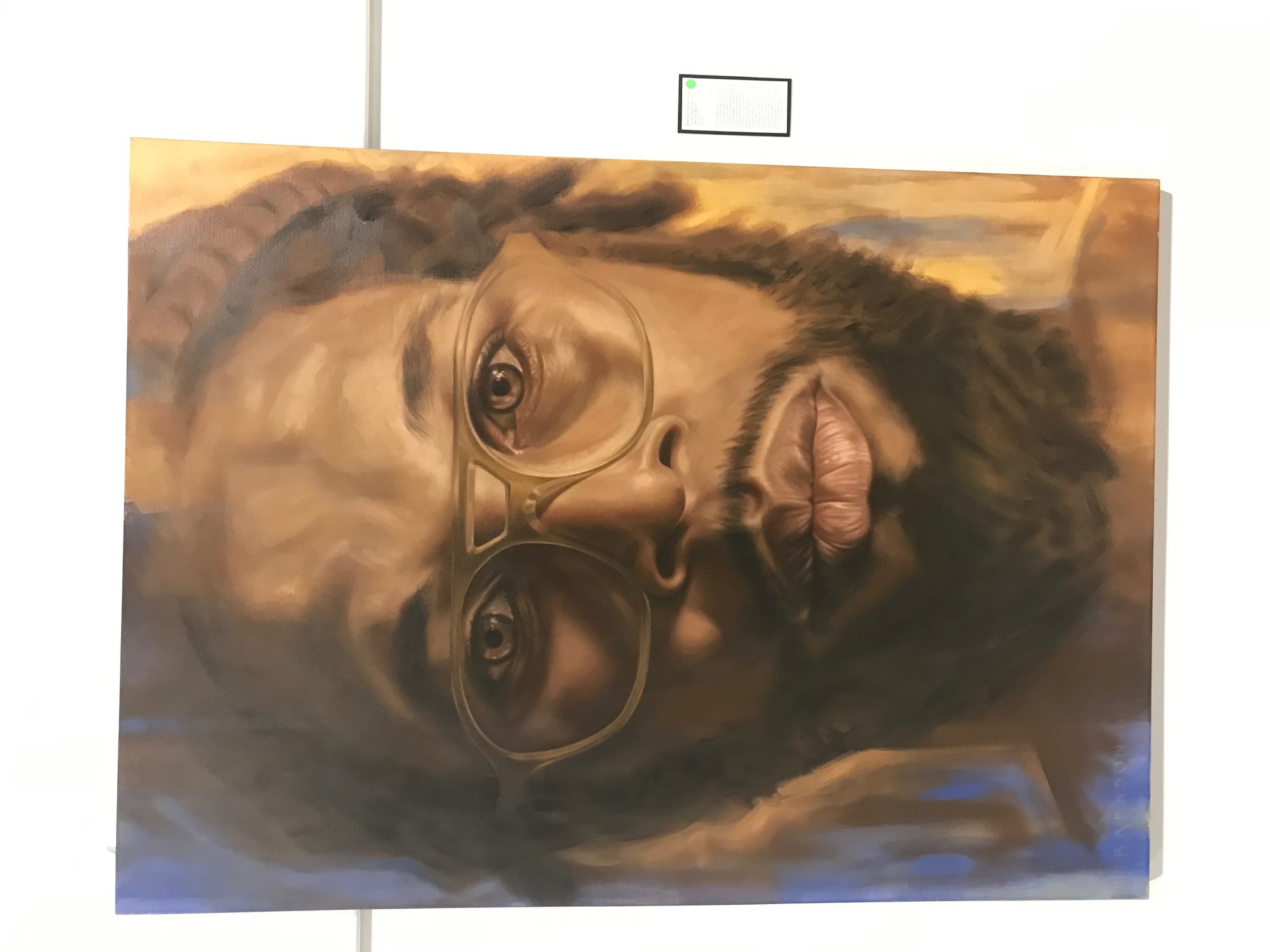

I didn’t know how important it was for me to go back and spend some time with this artwork, including Eric’s portrait of drummer Joe Dyson built on black, brown and beige tones. I know that it was more than I used to be an R&B drummer during my army days (1965 – 1968)–emphasis on “used to be”–that attracted me to the sticks and cymbal portrait of a young master drummer. Here Eric captures the dignity of our people and the rhythms we produce.

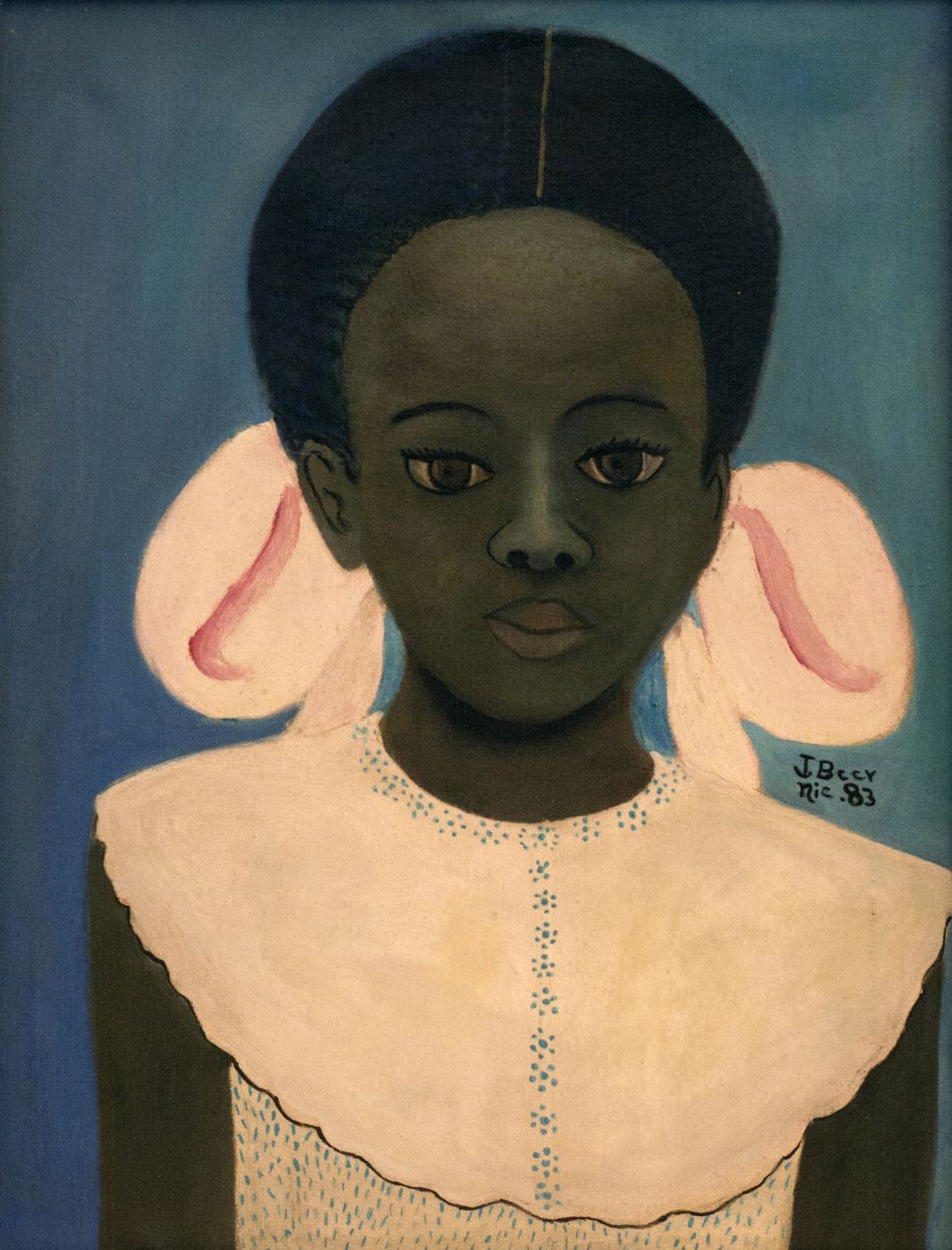

Far more than a mere snapshot, this visual essay struck my eyeballs in wonderment and encouraged me to closely inspect the whole assemblage of visual interpretations. I’m probably going to revisit the gallery for a third viewing. The totality of the artwork is so rich, one needs more than one or two bites to fully comprehend and digest this material expression of our outer beauty and inner soul.

I was enriched by what we see when we look at us. Deep into us. Archive, keep, and share ourselves with the world of New Orleans and beyond.

Our people are all up in here. Workers, visitors. Fam who look like some of the artwork on exhibit.

Sitting. Standing. Hands on hips. Mouths wide open in delighted surprise. All kinds of folk. Some looked like a brother who just walked in off the streets. A sister on her way to or coming back from church. Diaper-wearing toddlers running around, freely, untethered but not unwatched nor uncared for.

And music all in the air. Music. Music. You could easily dance here. They actually have Black music playing as an aural wallpaper while one views the artwork.

Plus, vendors with everything from home cooked food to colorful ethnic attire. Ethnic? A lot of our people wear a lot of this clothing everyday. The traditional marketplace and crossroads ethos reigns supreme here.

This is what it be like when a commercial boulevard becomes a stairway deep into the soul of the hood, the soul of ourselves.

You look into the window, and on one level or another, at one photo or another–maybe that statue on the left reminds you of your kinfolk. Or maybe not. But you will remember, later when the extended family gathers for a holiday. You will see that uncle you seldom see and he will remind you of something you saw, something you didn’t really remember until just now when a distant cousin laughs out loud.

Ashe Cultural Arts Center is a physical ring shout. A place to see. A place to dance. A place to be whatever you were in your boldest dreams. The vision you see at night when you close your sleepy eyes; the sunlit reality you vow never to forget as you prepare to face another day in this Babylon of a nation state.

Sister Asali commandeered a portion of the small piece of dough set aside by the city to purchase artwork for public use. This space is a venue not just for the viewing of art like a museum but way beyond that. In exchange for holding the exhibition here, they negotiated that the authorities would purchase selected pieces of artwork from the artists.

Plus, the people got to decide which art pieces they liked the best by stating their choices on a paper ballot–true democracy in full effect.

Of course like Duke told us, it wouldn’t mean a thing if it didn’t have that swing. That color. That forwardness. That joie de vivre. Look at how Val Rainey is smiling. She works there. Do you smile like that on your yolk, be glad to show people around your workspace?

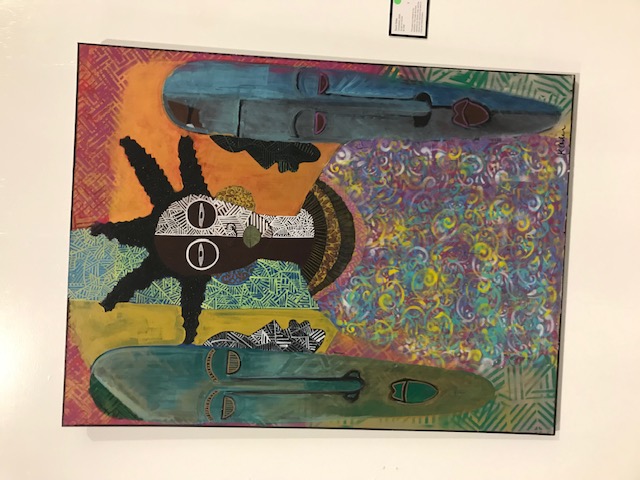

Some of this stuff could easily have made it into a so-called reputable gallery, others of the pieces–well, let’s just say the establishment wouldn’t touch some of this shit with a ten foot… you know what I’m saying? To be us is to be used-to-being overlooked, which is precisely why it is so great to peep what has been gathered at Ashe.

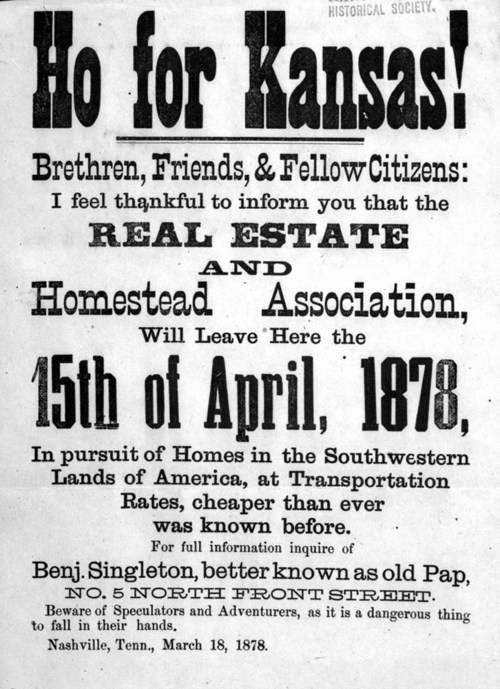

Check it. This is not just a random collection of some Black visual artists. This is us when our imaginations are raised full blast to well pass ten. Like, what looks like a lot of different, earth-toned blocks thrown together is actually a representation of Black skin tones and textures in New Orleans where we were forced into a ghetto by the strictures of the historic “brown bag” test.

What kind of test was that? Well, reduction ad absurdity, if you were darker than a brown paper bag there were certain social situations, places and gatherings operated by light-skinned negroes that would not allow darker-skinned folk to enter or join. I know, that’s crazy, especially since we all lived in a classist and racist society. Ah, but that was one of the downsides of the depressing aspects of a small sector of pre-Civil Rights era New Orleans: self-segregation administered by us on us in its most sinister hierarchy.

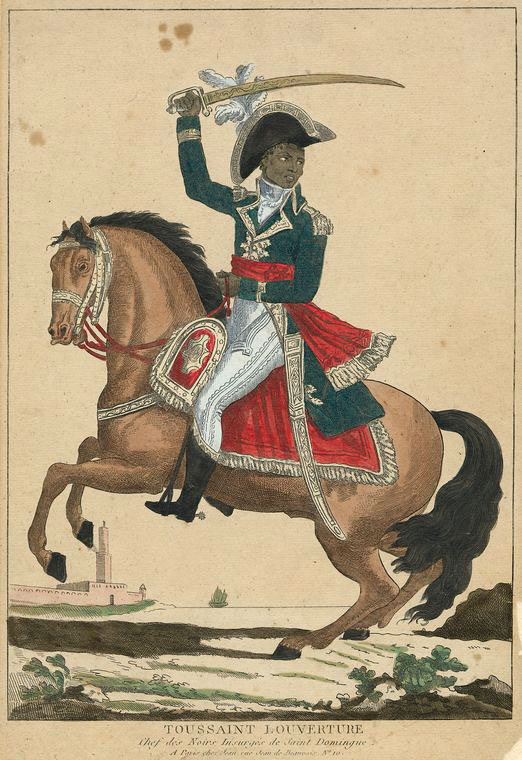

Black life in the gumbo of modern New Orleans is way different (and way better) today than it used to be a number of decades back when not only were we not all in the same boat, indeed, most of us were not even allowed into specific boats. We had to survive hanging on to driftwood or treading water or making our way in thrown together skiffs. Far too many of us didn’t make it. Like brother Jerry Butler sagaciously sang: only the strong (and/or the lucky) survived.

How one, seemingly simple abstract-geometric presentation of block shapes told this damning story is brilliant in cogently illustrating the complexity of a people deformed by White supremacy.

Dig, here is a detailing on canvas of what we look like in the multiplicity of sizes, shapes, and colors that resulted in a wide array of both biological and social, physical realities and social mores–part of what we are is a result of the too often, overwhelmingly forced introduction and intervention of Whites into our gene pool.

Only an Ashe could have pulled off an undeniably painful presentation of our historic suffering and nobody was cussing or crying or even much looking cross-eyed at someone else. Regardless of class and color differences, today we are one (or, at least, most of us strive to be).

A truthful artistic representation of who we are and how we came to be is not always just a self-congratulatory facade of pretty pictures but rather, a most intriguing and thoughtful examination of both our overwhelming beauty as well as certain of our most debasing moments.

Our truths are not always positive. We have to be honest and self-critical of some of the shit we went through. Fortunately, Ashe is a venue where the totality can be told, can be acknowledged even when there are some painful aspects some of us would deny or would rather not ever be revealed.

Ashe is a deep spirit house. We own, run, and maintain this facility; from brother Ed who does an incredible job pulling maintenance to sister Asali who is in charge of the whole shebang.

We need more of this. The United States is a big ass country. They got cities up, down, side to side. Urban and rural places with thousands of residents, as well as small municipalities and gathering spots, some of which are not even on anybody’s map. If I call some of the names of places located just around the Crescent City–Arabi, Chalmette, Marrero, Kenner, Shrewsberry, Slidell, LaPlace, not to mention Algiers on the West Bank of the Mississippi River, which is just about as old as New Orleans its self–most Americans would not know those spaces.

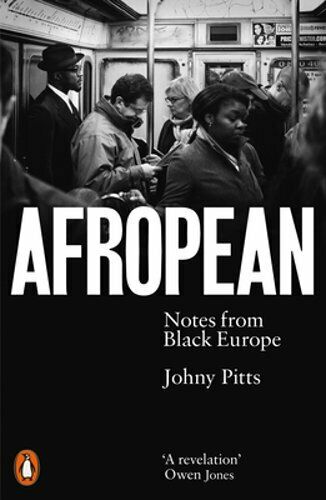

The point is although America is full of incorporated districts like our city, however, and regrettably, this country is not full of places like Ashe–places where the fullness of our story can be told in all its terrible beauty and complexity, and, yes, some elements of whom we have been are alarmingly depressing.

We got a lot of work to do, miles to go before we can rest, institutions to build, maintain and develop. Maulana Karenga, the creator of Kwanzaa, said it best: “Always remember we can always do more!” To which I would add, we need to, we must do more, much, much more.

There ought to be ten, twenty, literally thousands of Ashe initiatives north, south, east, and west. Right now there ain’t, but we can make it so. Not too long ago, there was no Ashe. Now Ashe receives bus loads of visitors.

Regardless of our longitude, our latitude, let’s just start wherever we’re at–and if the conditions are not forthcoming, well then move. Or at the very least, carve out your own small sacred space; create an altar to the departed: your ancestors, friends and family members who have transitioned.

Don’t worry about what we ain’t got nor who’s not here. Celebrate the victory gardens we have already grown, the people whom we have known. Embrace the here and now. Tend to and inspire those steady coming on.

The Art of the Black Experience show will be up until January 28, 2022. You will be surprised to see yourself in the mirror that art is. Get there if you can.

If you can’t, at least know that Ashe exists. Know that there is a place where the Black Experience is celebrated in all aspects of our bittersweet existence.

Ashe is our home no matter where we are from, no matter where we are going.